4e: Rites and Rituals

A complaint about 4th Edition Dungeons & Dragons was the ‘loss’ of a bunch of utility magic like Rope Trick and Leomund’s Hut. Typically, I hear it framed as the wizard specifically lost something by having its powers reduced to just the ability to fire off combat magic, and that’s kind of fair; when a character has a lot of utility effects in 3rd edition, if they were all gone and left only the combat stuff behind in 4th edition, it’d definitely be a limitation in scope.

The problem of course is that wizards lost none of their utility nonsense, and that utility nonsense was made more available to more characters, because if it wasn’t a combat effect, it was folded into the space of rituals.

Rituals are basically spells, but they’re spells that are too complicated and time consuming to perform in combat, and give you a kind of effect that the game doesn’t want you to just dump anywhere, at any time, for free. This was one of the problems with 3rd edition magical effects; some of them made major, common impediments to plots into trivial actions that a player character could renewably blast through – things like Speak to Dead and Teleport Without Error aren’t utility effects for combat, but are just plot-busters.

In 4e, all of these utility effects are created not as magical items that let you do the utility effects (as many of them became in 3rd, with scrolls and wands occupying the ‘nice but rarely needed’ spell slots), but rather as a straight up exchange for something your character can do, with the right components and a book. It’s great, honestly, since back in 3rd edition, as builds evolved over time, players would eventually just get in the habit of keeping cash on hand to pay the local cleric or wizard or whatever to cast the spell they needed for whatever inconvenient bullshit they were dealing with.

How do they work?

Basically, you can either buy a ritual scroll, which is a one-off, purchaseable version that needs no expertise. You need the effect once and you don’t imagine you’ll have value out of getting it regularly, so you buy the ritual scroll and go for it. Anyone can do that.

But if you want to do the effect multiple times, it’s cheaper (long term) to take the Ritual Caster feat, and transcribe that scroll into your ritual book. That means it’s mastered. And when it’s mastered, you can do it any time you want by expending components.

Okay, okay, components, that’s the next thing, what’s that mean. Well, there’s a generic purchaseable thing called ‘components’ for each skill. You spend gold on buying a quantity of Components, and then you use those components to do the rituals when you need to.

This turns these things into an expendable resource, something you can’t just overuse to solve every problem, but as you level up, they become more affordable, and you start being able to spend a small quantity of this resource on making some problems go away. Knock costs 35 gp and a healing surge – meaning that at the low level, the gold is a serious cost, at high level the healing surge is. But it also means that you can play a character who spends, by mid level, spare change on the magical effects that, in 3rd edition, you’d never use because to use them would involve spending a spell slot – something that’s really valuable.

Plus, as with a lot of things in 4th edition, this opens up a lot of character options. Let’s say you want to play a fighter who’s learned a trick or two from mages. Then you can take the Ritual Caster feat – in combat, you’re still a knuckle-dusting badass who uses swords and axes and shields and whatnot, you didn’t become a wizard – but now you know how to magically undo a lock, or create an illusion. Same thing with a rogue, who can complement their thievery with teleportation rituals!

There’s also the Martial Practices system, which adds Ritual Like Effects to the non-magical characters – stuff that definitely should take some time and effort to do, but shouldn’t need to be done by a wizard in a pointy hat.

I really like the ritual system! It’s one of those super neat components of 4th Edition that’s been seemingly rendered invisible in a sea of bad faith arguments, and that’s a damn shame.

How To Be: Chandra Nalaar (In 4e D&D)

In How To Be we’re going to look at a variety of characters from Not D&D and conceptualise how you might go about making a version of that character in the form of D&D that matters on this blog, D&D 4th Edition. Our guidelines are as follows:

- This is going to be a brief rundown of ways to make a character that ‘feels’ like the source character

- This isn’t meant to be comprehensive or authoritative but as a creative exercise

- While not every character can work immediately out of the box, the aim is to make sure they have a character ‘feel’ as soon as possible

- The character has to have the ‘feeling’ of the character by at least midway through Heroic

When building characters in 4th Edition it’s worth remembering that there are a lot of different ways to do the same basic thing. This isn’t going to be comprehensive, or even particularly fleshed out, and instead give you some places to start when you want to make something.

Another thing to remember is that 4e characters tend to be more about collected interactions of groups of things – it’s not that you get a build with specific rules about what you have to take, and when, and why, like you’re lockpicking your way through a design in the hopes of getting an overlap eventually. Character building is about packages, not programs, and we’ll talk about some packages and reference them going forwards.

This month, we’re going to talk about the hottest of Pansexual Messes, Chandra Nalaar and you may be asking me ‘well why didn’t you do that during Pride Month?’ and the answer is because Wizards have not been exactly well behaved on this issue and I’m not about to do their marketing work for them just this moment thank you bloody much. Instead we’re going to talk about Chandra on her own time, thank you very much.

4e: The Dragonborn

You may remember a while ago I talked about how, typically, in fantasy stories, dragons are used to represent governments. This idea isn’t like, hard codified facts or anything, it’s just a way to look at dragons and it can make some sense of how they behave when they’re used in stories. The thing is, that’s a sort of high-up view of what dragons are used for, and the ways we treat dragons because it’s the way we learned to treat dragons; they are, essentially, governments that you can interact with on an individual, personal level, which means that they can be petty and cruel and vain in ways that only involve changing one mind to fix or they can be benevolent and kind in the ways that an individual making reasonable judgments can.

But what if dragons were not only expressed in these forms, what if the role of the dragon in a story being a person means it is something that people can observe, can admire, can disconnect from its duties and the scope of its powers, and consider as a person that can be swayed, can be hungry, can have material needs, can-

Look, I’m circling around the question of whether or not Dragons Doink.

The Points of Light

Recent conversations about racism in D&D-

Oh yeah, uh

This isn’t going to be about that. That’s a pretty heavy thing. This is a light one.

How To Be: A Squid Maid (In 4E D&D)

In How To Be we’re going to look at a variety of characters from Not D&D and conceptualise how you might go about making a version of that character in the form of D&D that matters on this blog, D&D 4th Edition. Our guidelines are as follows:

- This is going to be a brief rundown of ways to make a character that ‘feels’ like the source character

- This isn’t meant to be comprehensive or authoritive but as a creative exercise

- While not every character can work immediately out of the box, the aim is to make sure they have a character ‘feel’ as soon as possible

- The character has to have the ‘feeling’ of the character by at least midway through Heroic

When building characters in 4th Edition it’s worth remembering that there are a lot of different ways to do the same basic thing. This isn’t going to be comprehensive, or even particularly fleshed out, and instead give you some places to start when you want to make something.

Another thing to remember is that 4e characters tend to be more about collected interactions of groups of things – it’s not that you get a build with specific rules about what you have to take, and when, and why, like you’re lockpicking your way through a design in the hopes of getting an overlap eventually. Character building is about packages, not programs, and we’ll talk about some packages and reference them going forwards.

And now, it’s Pride Month! Since I haven’t done one of these on a single straight character yet (if you believe my fanfics), I had to do something a bit special and out of the ordinary, and so, let’s do something that’s extremely culturally important.

That’s right. It’s Squid Maids time.

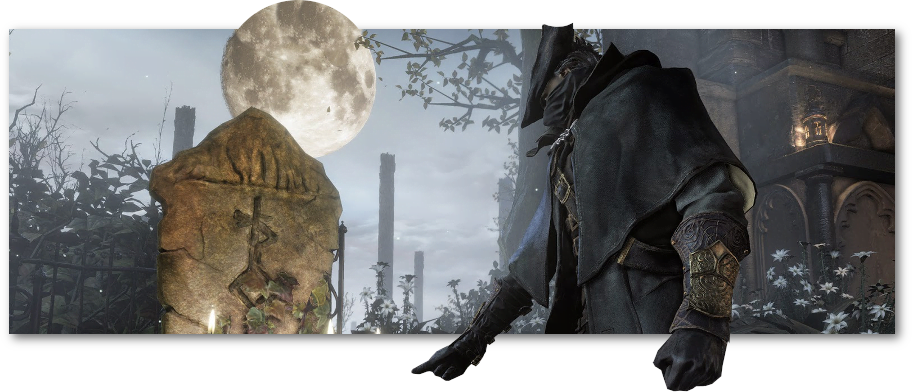

Hunters Dream – Building Building Encounters

This is more work on Hunter’s Dream, a 4th Edition D&D-compatible mod made to enable a Bloodborne style of game, where players take on the role of hunters, who have to first research their prey before going out to the tactical combat stage of things where players get to have cool fights with werewolves and whatnot.

The whole point of using 4th Edition D&D to form the basis of Hunter’s Dream is that it’s a comprehensive combat engine, with interesting tactical choices, and a philosophy of player engagement tha rewards tactical attention to detail. It’s a good combat engine, it does a lot of stuff I like. This includes things like the level of control players have over enemy movement, the way player powers are reliable, and the way players have clear information about the way their powers are meant to work. There’s not a lot of nilbog-style ‘surprise, idiot‘ stuff in 4e D&D, and not as much Grick-style ‘Why won’t this thing die’ nonsense you saw in 3.5.

That means that in my mind at least, a lot of Hunters Dreams games are going to be made up of players doing investigatory work, connecting to their community, digging into information, doing tasks to build tools, and eventually deducing things like nests or sites, solving murder mysteries or finding themselves trapped in the wrong place at the wrong time, and then, rather than ‘exploring a dungeon’ combats break out as short sequences of combat, comparable in scope to Dungeon Delve encounters.

How then, do I make that happen?

Here’s where unbelievably, you might be surprised, my brain goes not to tools, but to page counts. Ostensibly, I’d like for Hunters Dream to be a book, distributed to users. I’d like it to have art in it, and be professionally edited, and I’d like maybe, maybe, for it to be printable, in a way people can have in their own homes.

I’d also like it if the game was contained. I like distributing games in contained ways – I don’t like telling people they need expansions to make a game work. That means that anything I do for games, I tend to think in terms of a minimal expenditure for the consumer. If that’s how I’m thinking, then the possible scope of the book – and cost of it – become an important factor to consider.

Yeah, even at this point!

One of the big complaints about 4th Edition D&D is book bloat. If you collected 4e, even if you weren’t buying a lot, you might still have dozens of hardback books, and there are probably dozens more. It’s one complaint about the game’s model that people bring up that I do think is genuinely worth improvement. There’s a cousin complaint about how D&D ‘fools’ people into spending money on three books, instead of just buying one, which…

Indie friends.

Please.

Stop.

Anyway, if you need two or three books to run Hunter’s Dream, then the game just as a matter of necessity is harder to run. You need to flip between different books to get the game going, and that’s not great. On the other hand it isn’t like I think Hunter’s Dream can replace your Player’s Handbook and Adventurer’s Guide, per se? Because those books have all sorts of other stuff in them, like numerous classes and gear. If I try to make Hunter’s Dream into a one-stop shop for all the stuff you need to play, the book will be enormous, and expensive to make, and probably be too cumbersome to easily use for players who are interested in it. Twenty bucks on your own Player’s Handbook is a different kind of entry point than a hundred dollars on a book you’re largely not going to need.

I’ve said that games are a machine that creates a story. Well, an RPG system is a machine that creates a machine that creates a story. With that in mind, and I am literally reasoning this out as I write this, I think the step before designing encounters for Hunter’s Dream is to get my head around how the design for encounters should even be approached.

Specifically, as much as I’d like to present in Hunter’s Dream a set of encounters and monsters so you can select the monsters for an encounter easily and quickly, that eats up page space, and that page space eats up a lot of volume that players need for things, and the thing is, people who run this edition of D&D can get themselves monster resources in another way. That is really rough, too, because it means that if you got into Hunter’s Dream and it was self-contained, there’s that wealth of content out there that you may have that I’d be telling you to not look at because I personally hadn’t vetted it.

With that in mind, I think then, that the encounter design in hunter’s Dream needs to have new guidelines and new ways to design thematics and things like ongoing mechanics for specific monsters that are campaign specific, but the fundamental systems that underpin the thing need to be about telling you how to crack open your Monster Manual rather than telling you to throw it away. I need to put the top hats on the werewolves, I don’t need to reinvent the werewolf.

How To Be: Gardevoir (In 4E D&D)

In How To Be we’re going to look at a variety of characters from Not D&D and conceptualise how you might go about making a version of that character in the form of D&D that matters on this blog, D&D 4th Edition. Our guidelines are as follows:

- This is going to be a brief rundown of ways to make a character that ‘feels’ like the source character

- This isn’t meant to be comprehensive or authoritive but as a creative exercise

- While not every character can work immediately out of the box, the aim is to make sure they have a character ‘feel’ as soon as possible

- The character has to have the ‘feeling’ of the character by at least midway through Heroic

When building characters in 4th Edition it’s worth remembering that there are a lot of different ways to do the same basic thing. This isn’t going to be comprehensive, or even particularly fleshed out, and instead give you some places to start when you want to make something.

Another thing to remember is that 4e characters tend to be more about collected interactions of groups of things – it’s not that you get a build with specific rules about what you have to take, and when, and why, like you’re lockpicking your way through a design in the hopes of getting an overlap eventually. Character building is about packages, not programs, and we’ll talk about some packages and reference them going forwards.

And now this time, because you on the Twitters voted for it (whether or not you realised you were voting for it specifically), this month’s choice is the elegant mind dancer Pokemon, Gardevoir.

Continue Reading →4e Power Sources

Back in the olden days of Fourth Edition, we would cast our minds back to the even oldener days of Third Edition and the slightly less oldener days of Third Point Fifth Edition, all of which predates Fifth Edition, about which, I want to underscore, and reiterate, because I keep having to do this, I know nothing and do not care to know anything. Anyway, back in third edition, there were these terms for magic – arcane and divine. The rules around these mechanics were the kind of thing you’d look up once, then never need to remember again because they only mattered for setting some basic rules. The basic rules being that divine spells didn’t incur ‘arcane spell failure’ and arcane spells did. You had to know whether you did arcane spells or divine spells, but you didn’t really need to know much more about it than that.

There were some splats, some supplemental rules that sought to make the ‘martial’ type a thing, there was some vague wuffling about shadow powers and even once, an entire splatbook about introducing different types of magic to the game that were all, in their own way, terrible, and even involved just being arcane and divine in places, as the code that the game ran on really, really wanted a reference point for that information.

Fourth edition, though, looked at this sort of ‘power source’ idea and asked the question: what if we actually used this game flag for something?

So we got, in the first book, the power sources Arcane, Martial, and Divine. Later books introduced Psionic and Primal, and I guess Shadow exists, somewhere, over there. We don’t talk about Shadow, not here, and not in the Sonic fandom.

Now, hand to my heart, if you go looking in 4th edition for a power or ability that says something like ‘when an opponent attacks you with an arcane spell, do a thing,’ I don’t think you’ll find anything but I’m not entirely sure. They did try some experimental stuff in places in that game. But broadly speaking, you do not find things that reference power sources in the way that they were referenced back in 3.5 D&D! There was no armour attribute that only mattered to arcane characters (and which almost every arcane character class had some way around god damnit 3.5).

Instead, power sources in 4th edition were used in two ways:

- To give the different classes with the same power source a linked mechanical feel

- To give characters with a specific style multiple different mechanical opportunities

This may sound like not much, but it’s a hugely useful part of the game and it isn’t something you need to care about. As a designer, being able to say ‘primal characters tend to get these special effects’ is handy set of tools. As a DM, knowing that you have (for example), a group with Primal and Martial characters suggests to you that you’re not likely to have big spread AOEs or super-flexible powers like if you were dealing with Arcane characters. Martial characters care a lot about weapons and combat advantage, Arcane characters tend to have flexible special abilities, Divine characters tend to have heavier armour options, Primal characters tend to have more hit points and Psionic characters get power points.

And nobody cares about Shadow.

You may want to build your character, knowing you want a Ranger and that’s it, oh kay, so much, no problem at all. But if you don’t approach the class system that way, 4th edition’s power sources are here for you. Let’s say you conceive of a character who’s a bit rough around the edges, lives in the woods, tracks their own food and knows how to win a fight, and maybe has a pet. In 3rd edition, you have two options: the Ranger and the Druid. The ranger is a melee damage dealer (or you can try range if you want to be bad) and the druid is … ostensibly, a full spellcaster, and in actuality, brokenly powerful all singing all dancing shitting god-king of numbers mountain. But that’s it, that’s your options; a heavy caster, and a light caster who stabs things. Fox has said that I should add the Barbarian and I am even though I definitely wouldn’t if she didn’t.

But in 4th edition, if you wanted to play that same character, the woodsy outdoor type, you could play a melee damage dealer (ranger), a ranged controller (hunter), a shapeshifting monster person controller (druid), a shapeshifting monster person with a weapon tank (warden), a summoner with healer ghosts (shaman), an angry person with a weapon who hits people real hard (barbarian) and even another, different kind of ranged controller (the seeker, which we don’t talk about). They’ll have unified feels – they’ll all be nature-y, they’ll have nature-skills, they’ll work well for the story space you want to put them, but they’ll all be different mechanical choices with the same thematic space. This matters a lot, because suddenly, players can make choices that are about what they want a character to feel like without needing a super-refined grasp on a thousand rule options to make a build work (like back in 3.5).

See also, the divine. If you wanted to be a religiously chosen holy crusader type in 3.5, your options were Paladin and Cleric (which was also broken). That is, a pair of melee, heavily armoured combatants, who usually wore a shield and cast spells at the direct behest of a god, with some smiteyness thrown in. In terms of differences in style, the cleric didn’t have a horse and the paladin didn’t get to be strong enough to piss in god’s ear. But in 4th edition, if you want to play that same divine, holy crusader type, you have clerics, paladins, avengers, invokers, runepriests and blackguards (who can join the Seeker and Shadow).

These options are all kind of just washing over you at this point, I know, but this is a really important bit of design technology. Unifying thematic space gives players more room to make their own thematic choices. If there’s one way to be something in your world, any player who wants to be that thing can only be that thing.

Power Sources are one of many things in 4th edition D&D that made the game better, and part of what makes them exceptional design technology is that if you didn’t care you never had to notice the bloody things at all.

How To Be: Corvo Attano (In 4E D&D)

In How To Be we’re going to look at a variety of characters from Not D&D and conceptualise how you might go about making a version of that character in the form of D&D that matters on this blog, D&D 4th Edition. Our guidelines are as follows:

- This is going to be a brief rundown of ways to make a character that ‘feels’ like the source character

- This isn’t meant to be comprehensive or authoritative but as a creative exercise

- While not every character can work immediately out of the box, the aim is to make sure they have a character ‘feel’ as soon as possible

- The character has to have the ‘feeling’ of the character by at least midway through Heroic

When building characters in 4th Edition it’s worth remembering that there are a lot of different ways to do the same basic thing. This isn’t going to be comprehensive, or even particularly fleshed out, and instead give you some places to start when you want to make something.

Another thing to remember is that 4e characters tend to be more about collected interactions of groups of things – it’s not that you get a build with specific rules about what you have to take, and when, and why, like you’re lockpicking your way through a design in the hopes of getting an overlap eventually. Character building is about packages, not programs, and we’ll talk about some packages and reference them going forwards.

This time, we’re going to try and capture the feeling of the Knight Protector of the Empress of Dunwall woops oh no it’s all gone wrong, Corvo Attano.

Oaths, Pacts and The Moral Failure of Trying

A lot of D&D players view their D&D world like they’re a bunch of cowards.

Continue Reading →How To Be: Thor, from Marvel Comics (In 4E D&D)

In How To Be we’re going to look at a variety of characters from Not D&D and conceptualise how you might go about making a version of that character in the form of D&D that matters on this blog, D&D 4th Edition. Our guidelines are as follows:

- This is going to be a brief rundown of ways to make a character that ‘feels’ like the source character

- This isn’t meant to be comprehensive or authoritive but as a creative exercise

- While not every character can work immediately out of the box, the aim is to make sure they have a character ‘feel’ as soon as possible

- The character has to have the ‘feeling’ of the character by at least midway through Heroic

When building characters in 4th Edition it’s worth remembering that there are a lot of different ways to do the same basic thing. This isn’t going to be comprehensive, or even particularly fleshed out, and instead give you some places to start when you want to make something.

Another thing to remember is that 4e characters tend to be more about collected interactions of groups of things – it’s not that you get a build with specific rules about what you have to take, and when, and why, like you’re lockpicking your way through a design in the hopes of getting an overlap eventually. Character building is about packages, not programs, and we’ll talk about some packages and reference them going forwards.

This time, we’re going to try and capture the feeling of THE GOD OF THUNDER Thor from Marvel Comics.

4e: Claw Gloves

4th Edition D&D is, like all editions of D&D, very much invested in the physical stuff your character carries around. I’ve talked about this in the past,where D&D finds it easier to use material objects to give you preposterous abilities, even though it’s ostensibly a game about wizards with preposterous abilities. In 4th edition, there was a formal, searchable databse for equipment that meant if you were the kind of player who wanted to find a specific, passive, always-on effect to put on your character, you could always find something to get your hands on – or in this case, in.

There’s a bunch of items that are designed to be Heroic tier prizes, items that are pretty cheap and have a really nice effect, but don’t scale up at all, usually in a slot that is either hotly competitive (arms) or tends not to matter much (boots). These items in Heroic tier are really nice – often things like Rushing Cleats or Badge of the Berserker will serve you really well and help you shape your character as you level up.

Claw Gloves are designed for druids, which is why they reference a specific keyword that druids get, ‘beast form.’ If you have claw gloves on, and you’re in beast form, and you have combat advantage against an enemy, your melee attacks are improved by 1d10. Combat advantage, something you already want, becomes extremely desireable when you’re dealing chunks of extra damage, and this is a passive property, meaning it’s not a sometimes food. Any time you can make those things happen, you have the extra damage.

For druids, that’s great, making their beast form – already a control monster – into a really strong damage dealer in Heroic. Claw gloves are great.

Thing is, Druids aren’t the only ones who can get access to Beast Form, and thanks to the Werebear, Wererat and Werewolf themes, every other class can have a ‘beast form’ mode to their melee attacks. Once you get out of Heroic, into Paragon, the lycanthropes can just ‘always’ be in beast form, meaning there’s no reason to drop out of it, allowing for full time furry character interpretation (and it lets you define yourself how that looks). This means that suddenly, Claw gloves work just fine for Fighters, Rogues, Rangers and Battleminds. Anyone who does melee attacks and multiattacks gets a lot scarier when this one very cheap item in an underused slot is pumping extra d10s into their attacks.

What’s more, once you commit to going ‘well, claw gloves look cool, can I use them?’ you wind up at beast form, and then all those beast form feats stack up, and you’re suddenly presented with, say, a Werebear Grappling Fighter who tucks enemies under her arms as she wades across the battlefield, and when they try to escape she crushes them then throws them across the battlefield.

Claw Gloves are great, numerically, but the thing is that they serve as a thread you can search through for building your character, and that’s exciting. What’s more, if you don’t want to do that nonsense, you can just get handed the item, go ‘oh, that’s not for me’ and move on.

In conclusion, fear the furries.

The original art for the claw gloves I used is from a store called Stronghold Leather that appears to have since shut down and the only remnants of their work remains as pinterest boards.

4E: Harnessing Hotness

Alright we’re going to talk about some base assumptions about character building in Dungeons & Dragons and they’re going to relate to hotness. I’m deliberately leaving this super ambiguous, because hotness is always relative and you get to decide the ways in which you’re hot, but it’s a common, reasonably accepted shorthand that in D&D, if you have high charisma, you’re appealing. Stats are flexible, your flavour is your own, everyone’s character can devise their own explanation for their abilities, but if you want to play a character who’s really hot, and want that hotness to be mechanically obvious, one of the easiest and most commonly accepted ones is high charisma. This is the place we’re starting from.

How To Be: Ranma Saotome from Ranma 1/2 (In 4E D&D)

In How To Be we’re going to look at a variety of characters from Not D&D and conceptualise how you might go about making a version of that character in the form of D&D that matters on this blog, D&D 4th Edition. Our guidelines for this kind of project are as follows:

- This is going to be a brief rundown of ways to make a character that ‘feels’ like the source character

- This isn’t meant to be comprehensive or authoritive but as a creative exercise

- While not every character can work immediately out of the box, the aim is to make sure they have a character ‘feel’ as soon as possible

- The character has to have the ‘feeling’ of the character by at least midway through Heroic

When building characters in 4th Edition it’s worth remembering that there are a lot of different ways to do the same basic thing. This isn’t going to be comprehensive, or even particularly fleshed out, and instead give you some places to start when you want to make something.

Another thing to remember is that 4e characters tend to be more about collected interactions of groups of things – it’s not that you get a build with specific rules about what you have to take, and when, and why, like you’re lockpicking your way through a design in the hopes of getting an overlap eventually. Character building is about packages, not programs, and we’ll talk about some packages and reference them going forwards.

This time, we’re going to try and capture the feeling of gender-flipping Martial Arts Death Machine Ranma Saotome from Ranma 1/2.

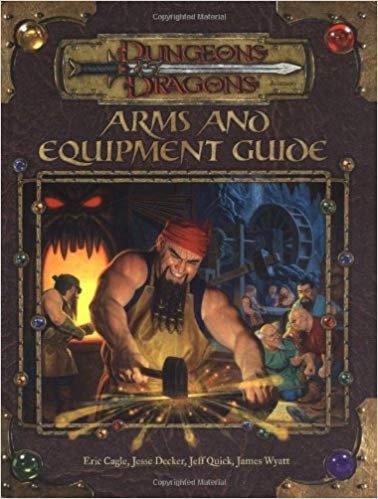

The Immaterial Material: D&D’s Stuff

You know for all that D&D is seen as a story of heroic fantasy it’s awfully bitsy. I don’t just mean the way that D&D is a game that encourages a truly remarkable amount of special acquisition of items for play – how many people do you know who have a miniature for their characters? – I mean that the story that plays out in the game winds up being about stuff. Lots and lots of stuff.

I’ve been writing about ‘stuff’ in games lately, reading about how we treat material objects, and while there’s definitely a different kind of materiality when you talk about a playing card, a dice and a meeple versus the text on a page that reads +3 longsword, there’s still something to be said about the way that D&D, 3.5 and 4e especially (because those are the editions I know) focus characters over an inevitable wardrobe full of stuff.

Now, there’s a reason for this, and it gets at one of the basic assumptions of the game that D&D wants to be. D&D ostensibly is a game about heroic fantasy, but connected to the idea of this heroic fantasy is a need for adventurers to be mostly, heroically empowered but still fundamentally scaled heroes that can be compared to normal people. It’s not the X-Men, it’s a place where your hero who swings a sword can’t be expected to cut through the bars of a prison, but if that sword was magical, then they could.

Now, this isn’t a bad thing per se, but it does tell you something of the basic assumptions of a world like Dungeons & Dragons and it’s a basic assumption that I’m used to seeing in a lot of, of all things, first person shooters. Yes, I’m probably going to talk about DOOM again, maybe.

When you start to talk about what stuff is used for in D&D, it’s pretty easy to see that stuff can do a lot more than people can do. People are limited, they’re made of meat, and they’re not capable of long-lasting, permanent effects. Even the wizard has to spend spell slots to fly, but a pair of winged boots will take you into the air as long as you like. The boots are expensive, and that’s another element (the relentless roll of capitalism).

One other thing is that items can be systematised, because objects, we believe, behave consistently and repeatedly. Despite the fact that the D&D world is typically represented as pre-industrial (except the good ones), these items are made and represented as if they are in their own ways kind of mass-produced; a jagged fullblade from one continent will work the same as a jagged fullblade from another.

This is another funny detail about this worldview: The items you’re building and examining are being treated as if they’re just making a thing that can exist; it’s not a matter of someone choosing to create something to overcome a task or have an effect (and indeed, if you approach a DM with a specific request for an item function that isn’t from the existing ruleset, that can be seen as asking for something ‘too specific’). It’s not that you made a weapon that does more damage when it hits an opponent in a vulnerable moment – it’s that you made a jagged or vorpal weapon, and those existing elements have math to them.

Stuff gets to be consistent! Stuff gets to work, and keep on working! We live in a world full of machines that work consistently until broken, and it seems that that plays into how we want magical devices to work in D&D. We don’t find that unrealistic, that a character can wander around in a small town’s economy’s worth of super-specialised consumer goods that literally nobody non-Adventurey could afford to meaningfully buy, we don’t find it unrealistic that these objects can be somehow mass produced and we don’t find it odd that these things can do much more than a person can do, because we accept that it’s okay for objects to do these things…

… and that it’s not acceptable for people.

This plays into the way that the worlds of D&D are made, by the way. Not only are places like the Realms and Eberron full of underground caches full of fantastically expensive and yet still practically useful antique hardware, they’re also places that mysteriously have investors and traders who can be bothered making these goods and trying to sell them on despite their fantastically obvious market problems.

This relationship to stuff is one of the things that breaks easily when you start trying to use D&D for other stuff. Infamously, the game D20 Modern tries to dispense with the relationship to stuff, making mose equipment mundane and focusing the game instead around the ‘wealth check’ that gave you a general idea of what you were capable of buying. The result was that your stuff suddenly didn’t feel like it mattered, but your character never mattered as much as their stuff – so you mostly spent your time piloting around a pair of guns and a skill list.

How To Be: Edward Elric from Fullmetal Alchemist (In 4E D&D)

In How To Be we’re going to look at a variety of characters from Not D&D and conceptualise how you might go about making a version of that character in the form of D&D that matters on this blog, D&D 4th Edition. Our guidelines for this kind of project are as follows:

- This is going to be a brief rundown of ways to make a character that ‘feels’ like the source character

- This isn’t meant to be comprehensive or authoritive but as a creative exercise

- While not every character can work immediately out of the box, the aim is to make sure they have a character ‘feel’ as soon as possible

- The character has to have the ‘feeling’ of the character by at least midway through Heroic

When building characters in 4th Edition it’s worth remembering that there are a lot of different ways to do the same basic thing. This isn’t going to be comprehensive, or even particularly fleshed out, and instead give you some places to start when you want to make something.

Another thing to remember is that 4e characters tend to be more about collected interactions of groups of things – it’s not that you get a build with specific rules about what you have to take, and when, and why, like you’re lockpicking your way through a design in the hopes of getting an overlap eventually. Character building is about packages, not programs, and we’ll talk about some packages and reference them going forwards.

This time, we’re going to try and capture the feeling of Edward Elric from Fullmetal Alchemist: A Lot Of Different Things.

How To Be: Hilda From Fire Emblem Three Houses (In 4E D&D)

In How To Be we’re going to look at a variety of characters from Not D&D and conceptualise how you might go about making a version of that character in the form of D&D that matters on this blog, D&D 4th Edition.

The rules for these posts are going to be standard and yes I am writing something that’s going to be the boilerplate that becomes the core of how all these posts are going to get made going forwards, but here we go anyway:

- This is going to be a brief rundown of ways to make a character that ‘feels’ like the source character

- This isn’t meant to be comprehensive or authoritive but as a creative exercise

- While not every character can work immediately out of the box, the aim is to make sure they have a character ‘feel’ as soon as possible

- The character has to have the ‘feeling’ of the character by at least midway through Heroic

When building characters in 4th Edition it’s worth remembering that there are a lot of different ways to do the same basic thing. This isn’t going to be comprehensive, or even particularly fleshed out, and instead give you some places to start when you want to make something, to give you a place to start.

Another thing to remember is that 4e characters tend to be more about collected interactions of groups of things – it’s less that you get a build with specific rules about what you have to take, and when, and why, like you’re lockpicking your way through a design in the hopes of getting an overlap eventually. Character building is about packages, not programs, and we’ll talk about some packages and reference them going forwards.

So for our first excursion into this idea, we’re going to start with Hil-Da, Hil-Da from Fire Emblem 3 Houses.

Half-Elves (But really Elves)

My earlier treatment of Orcs in Cobrin’Seil was intended, at first, to be a comprehensive examination of the half races. Elves and orcs and humans, the big three that show up in most of the editions of D&D’s player handbooks and most of the settings for them. As I did this though I realised that for all they may work just fine as different versions of the same thing for your setting, I don’t like them feeling so similar and especially not when I laid out my idea that Orcs are made of meat.

One of the questions this examination needs to answer is why are there half elves and half orcs? Perhaps a permutation would be why them and not half-other things? Some settings even answer that with things like the Mul, or half-centaurs or half-catfolk or so on. In that case, the halfness comes from a fundamental trait of humanity. I can buy that? Some people like it when humans’ ultimate flexibility includes with whom they can breed. It certainly fits the human cultural tendency to fuck things.

Continue Reading →Half-Orcs (but really Orcs)

I have these in my D&D setting, and I have them because, removed from any ontological questions, they are cool things. An orc is like a human, but bigger and usually more physically brawny, and green, and being able to play a half-orc means you have a bunch of outcaster cred, you get to play with the way you look in a way that’s got meaningful signifiers attached to it, and you can funnel your intentions through the lens of ‘how people see orcs.’ The orc – and the elf, but more on that another time – are perfectly good fantasy tools that let you play around with the space of meaningfully physically distinct humantypes, and half-thems are great tools for giving players a way to play as outsiders learning about their world.

Interesting things happen at borders.

I like ’em! But they often, in many settings, don’t make much sense. Part of why they don’t make much sense is how they relate to the half that gets mentioned, the not-human part of orcs, and why they can breed with humans. Questions get asked, and I’m the kind of world builder who’s curious enough to want an answer, and an answer that doesn’t make me wrinkle my nose and go ‘well that’s stupid.’

With that in mind, and knowing these are creative toys for my friends to work with and designed to be played with, I want to make sure they’re something that has space in which to play. What then, do I want an orc to be in my settings?

Continue Reading →Hunter’s Dreams – Defining the Hunt

This is more work on Hunter’s Dream, a 4th Edition D&D-compatible mod made to enable a Bloodborne style of game, where players take on the role of hunters, who have to first research their prey before going out to the tactical combat stage of things where players get to have cool fights with werewolves and whatnot.

Something I really like from Blades in the Dark, something that I am shamelessly trying to bring to Dungeons & Dragons 4th Edition in Hunter’s Dream, is the degree to which players have a sense of agency over the game they’re engaging with.

There’s an existing mindset for D&D that games are basically one of two different kinds of play space. The first is often known as narrativist, where you treat every session, every encounter, as a sequence in a narrative, and so the whole game can be seen as a string of beads. This vision can be sometimes presented as a weakness, where the players are always confined by ‘the story’ that wraps around them like a tunnel. I’m not really here to criticise that, because hey, even the most railroaded game campaign can still be an interesting ghost train.

Then there’s a position, often called ‘simulationist’ which presents the idea that the players are just operating in a world, there’s stuff for them to do, and they can go do stuff at that world, and if it does all relate or connect to things, that’s just because the DM’s job is ‘running the world,’ and any narrative that ensues is emergent. I don’t think this is true either, but some people are fond of talking about it like that.

Neither of these perspectives suit well Blades in the Dark‘s style of player-driven fiction roleplay, and they don’t quite do the job of what I want for Hunter’s Dream. What I want for this is a hybrid model, with a Narrative running as a timer on a simulation, and a large part of that is formalising a system whereby players have direct agency over the tasks in front of them, and the order they handle them.

Now, 4ed is good for this because 4ed D&D is designed to handle a lot of small tactical encounters that are reasonably well-balanced with one another, where the alchemy between monster interactions are less likely to result in catastrophic failures. You’re not likely to find a lot of total dealbreaker combos if you throw enemies together semi-randomly, which means one of the things that it handles really well is generating sequences of small quantities of conflict without necessarily a lot of elaborate construction.

This asks for a robust system for constructing incidents quickly, giving DMs good sources of inspiration, and a clear vision of how they can execute on these encounters interestingly. Now I’m a sucker for this: In 4e, I’m a fan of using the same monster configurations from fight to fight and just changing the terrain around them and watching as players have to formulate different strategies to deal with them.

What I think of in Hunter’s Dream then is that players have a set of different competing needs, they choose what they’re going to go out and hunt, and why. This isn’t to leave players completely adrift, stuffing their characters into a monster pachinko machine – if you’re fighting random monsters of your level, over and over, you’re just going to feel like you’re throwing effort into a bin. What you need then is stuff to structure the kinds of encounters players are after, which I divide into four basic categories: Incidents, Schemes, Needs, and The Doom.

Continue Reading →Being The Monster: 5 Horrible 4e Heroes

Everyone I know has some hypothetical interest at the very least in playing a hot monster in their local tabletop game. I am willing to recognise that this is a selection bias, possibly due to the overwhelming presence of the queer monsterfuckers in my social circle, but the long and short of it is that I know people who regard the Monster Manual as less like a threat and more like Tinder.

The problem with making monstrous characters in most D&D games is that all the monsters you might want to be are gated behind a lot of rules baggage, like the hellscape of imbalanced garbage that is Savage Species back in 3rd edition. But what if in this season of spook, you want to make a monstrous character and just get rolling in my edition of choice? Here then are five spooky characters you can play from level 1 that let you get in the spirit of the season without needing to jump through a dozen hoops.

Five Reasons You Should Try Running 4e

Typically when these edition conversations come up, I come at it with a certain kind of defensiveness. This is in part conciliatory – after all, I don’t think the conversation is useful if it’s about whether or not you should play 5e or 4e (or 3e, or Pathfinder, or whatever). It’s not useful, because I have a straightforward answer that I think 4e is better than all of those other games, and I don’t care about hearing about those other games at all.

I know, it’s so unreasonable of me. I just don’t care.

Nonetheless, I often get asked afterwards, ‘hey, would you suggest I try 4e?’ and I usually say something to the effect of ‘hey, I don’t know, why not.’ This is in part because organising a tabletop game is a big pain in the ass. If I’m suggesting you branch out, is it really best to suggest you start by trying 4e, when there’s other, less difficult games to get rolling on, that will broaden your palate and give you a better appreciation for more games, and maybe even give some money to a deserving soul. Is it better to suggest you try 4e D&D than try Dog Bear or Brinkwood or Monster of the Week?

But let’s set that aside for now. Let’s assume you’re curious about a D&D game and are deciding between your options. Alright then, quick and dirty, here’s five reasons why you should try 4ed:

5. It’s Cheap

Perhaps thanks to its reputation and perhaps thanks to being a ‘dead’ game, 4th Edition D&D’s core rulebooks can be had for $10 each in pdf form, giving you a total of $30 to get started. The 5th edition Player’s Handbook is $50, and isn’t even all the resources you’ll need. You could buy the 3.5 PHB for the same $10, but I will point out, that game is really bad and falls apart when you look at it too hard. 4e, on the other hand, works, and that’s what we’re talking about here, geeze.

4. It’s Convenient

Hey, do you like homework? I don’t like homework. Other editions of D&D are set in settings with really specific tones and rules about how the world works, so if you make a character thinking about their flavour first, you have to double check rules to see if that’s true. This can be a real pain in the ass if you want to play something like a cleric or a druid and need to know how magic and your powers interact with your worldview.

4ed D&D doesn’t do that! There’s no pre-established setting you have to learn about while you’re just finding your feet. The world could be dense and rich in lore, it could be an existing story space you like, you could just use it to jam in another setting if you want, because it’s mainly concerned with making sure things work and not being too fussed about how.

3. It Works Great Online!

The 4ed resource set is one where the biggest complaint people have about its primary mechanical axis (the miniatures and tabletop space) is stuff that a lot of online tabletop spaces already cover. If you use Roll20 or Tabletop Simulator to run your game, you won’t need to do anything fancy to get the resources required to set up or play, because all those assets are easily googled and slapped on the tabletop conveniently.

This means that if you have a problem with getting players to the table, like people have commitments at home and the like, maybe you have a slot in your normal gaming group for a 4e game that lives in those downtime weeks.

2. It’s Fast

Combat in Dungeons and Dragons games is pretty slow, no matter what; there’s always some friction lost to checking initiative and turns and the round of the combat it’s in, and people considering their options and that’s just there. 4ed D&D combat is still about as slow as the editions around it, but 4ed does what it can to push that friction down.

When you’re making characters, roles let players stay out of each other’s ways and when you’re playing, roles let you get a clear idea of what your allies might need. What’s more, it’s pretty easy to make a character who, at level 1 works pretty much fine, and all your standard stuff you need to do your character’s job is guaranteed.

1. It’s Amazingly Easy To Run

The 4ed encounter builder is so robust that you can literally pick monsters at random, and there are even online resources to do that for you, and you will have your encounters pretty much put together. You can even use this to give you an explanation for the session – these four random monsters are in this level 1 encounter? Okay, why are they working together?

The back end of 4e D&D is really, really solid. If you’ve never run a game and want to try it out, 4e D&D is one of the systems that I hold out as a system that knows it has to explain things to you when you get started, and it puts good, useful tools in your hand.

So there!

D&D Memories: Adon

If people keep reading these I guess I’m gunna keep posting them.

Okay, so one night we sat down to play D&D and I had to admit that I was kinda tapped out and didn’t have a campaign to start up straight after one I finished. That’s how it went, I think – this detail isn’t super important because I’m not trying to gladhand myself over how much I run, I’m just wanting to make it clear that this was not a big planning moment.

A friend said he had an idea for a campaign, gave us a level, and asked us to make characters. This being 4ed, we had characters made within a few minutes, and we started out. That character creation being so swift though meant that we didn’t come at this with a lot of definition. One player stated boldly that he was playing a Dragonborn, named Maldracus, which,

it means ‘bad dragon,’

and no the player didn’t know.

That set the tone, though – quickly, the idea of a party of monstrous people came up. I wasn’t playing tank or leader this time, which I tended to do – instead, I was given free reign to play one of my long-time wants in the game.

I got to play a druid.

The 4ed druid is one of my favourite things. It has shapeshifting, melee damage, ranged control, a smattering of healing, and a lot of different ways you can focus your build just based on which of these things most excites you. You can even be a quitter and take a build that is a leader, giving up on sweet, sweet beast form, if you want. The book doesn’t specify what ‘beast form’ is, by the way, and you can choose what it looks like whenever you shapeshift, just that it is a natural beast (an animal) or a fey beast (an animal, but funky).

When I was asked to describe my beast form the first time, in an attempt to be impressive and thinking on the fly, I described a black jaguar, but made of vines. It’s 4ed, that sounds fey beasty, that’s great, we went with it. And what ensued then, as I fell into this character, was discovering my wonderful tentacle catboy.

See, once I had this idea of a kind of horrifying feyness to him, the character quickly took shape as clearly not actually an elf. Oh he looked like an elf and he had stats like an elf, but there was all this stuff that was wrong. His hair had tendrils in amongst it, that could move and shift about. He had prominent catlike ears, when administering medical aid he asked where another player character had their hearts, he acted surprised when he took out something’s blood, he just was off. And powers like Firehawk were reflavoured to be strange, bitingly cold holes in the world to another realm.

Basically, I played this druid as if the natural world he was connected to was a bit more Arthur Machen than Beatrix Potter.

Eventually, though we were asked to introduce ourselves by name to an NPC, and this tentacle catboy had to introduce himself. With no name springing to mind, I leapt for the name of the Nameless One’s fake (?) identity from Planescape: Torment: I called him Adon.

Adon got played for about half a year, I think. During that time we learned that druids can go where they want, that you can get a lot done with tentacles, we saw several opportunities to unload the toad and the character got steadily weirder and weirder, in ways I can only describe as chaste-horny. That is, Adon didn’t really have any horniness to him, but everyone could tell how upsettingly sexual things like ‘tentacle catboy’ was, even while Adon was mostly using his shapeshifting and nature powers to turn into a tangle of thorns and kick the crud out of people.

I really properly loved this character, partly as a sort of random grab-bag of parts all happening at once, but also because I’m a sucker for things that transform, and the nobility of his monstrousness all came together in a perfect way.

So hey, invite me to play your 4ed D&D game sometime, I might play an upsettingly sexy tentacle catboy.

Hunter’s Dreams – Trick Weapons, Part 3

This is more work on Hunter’s Dream, a 4th Edition D&D-compatible mod made to enable a Bloodborne style of game, where players take on the role of hunters, who have to first research their prey before going out to the tactical combat stage of things where players get to have cool fights with werewolves and whatnot.

Last time, I discussed how 4th Edition D&D’s weapon system works, and today, I’m going to lay out some basic ideas of actual mechanics for use in Hunter’s Dream.

Hunter’s Dreams – Trick Weapons, Part 2

This is more work on Hunter’s Dream, a 4th Edition D&D-compatible mod made to enable a Bloodborne style of game, where players take on the role of hunters, who have to first research their prey before going out to the tactical combat stage of things where players get to have cool fights with werewolves and whatnot.

Last time, I discussed the basics of what a Trick Weapon does in Bloodborne, and today, I’m going to talk a bit about how 4th Edition D&D can handle some of those ideas.One of the reasons wanted to do this in 4th edition D&D is because the weapon system in 4e is really good compared to every other edition of D&D. Without delving into why and how other systems were bad (but they definitely were), let’s look at the things the weapon system in 4ed D&D has.

A 4th edition weapon has the following basic stats:

- a proficiency type (simple, military, exotic)

- a handedness (one-handed or two-handed)

- a range (melee or distance)

- a damage range (one or more dice representing the damage the weapon does)

- a proficiency bonus (determining any bonus to hit the weapon has)

- a weight (for encumbrance rules, which I’m no fan of, but this is our life)

- a group (to represent what other types of weapons it’s like)

- properties (one of a set of keywords that give the weapon specific abilities)

The weapon properties are as follows:

- Brutal

- Defensive

- Heavy Thrown

- High Crit

- Light Thrown

- Load Free

- Load Minor

- Off-Hand

- Reach

- Small

- Stout

- Versatile

Some of these keywords are very specifically utilitarian – a thrown dart would have Light Thrown, while a throwing axe has Heavy Thrown. A light thrown weapon uses your dexterity, a heavy thrown weapon uses your strength. Some of these, like Load Free and Load Minor relate to the unifying mechanics of the set they’re in (Crossbows and how you load new crossbow bolts).

The main thing about these keywords is that when you’re using the weapon, these keywords are very light on your cognitive load. Consider Defensive. A defensive weapon is as follows:

A defensive weapon grants you a +1 bonus to AC while you wield the defensive weapon in one hand and wield another melee weapon in your other hand…

Now, this has a few things that relate to it – it could be seen as kind of ‘choice intense’. You get an AC bonus with the specific condition presented here, but you need to pair a weapon with the defensive type, and you need another weapon, which must always be wielded in one hand. So hypothetically, any time you put this weapon down, your AC changes, and any time the weapon in your other hand changes, that also has a chance to change your AC. In a videogame with things like disarms or throwing weapons, this could be pretty complex.

In 4e though, a character is not likely to be disarmed; they are likely to configure how their character works, the way they approach combat, and once that decision has been made, this defensive weapon bonus just folds into the way the character works.

Brutal is my favourite. Brutal N means that when you roll a value of N or less on the damage dice, you can reroll it. This is a great mechanic because it can be a small nudge, statistically (a 1d12 weapon with brutal 1, for example, is an increase on average of .5 damage per attack) but it can feel really fantastic to cash in a 1 for even a 4. What’s more, some brutal weapons prevent feel-bad low rolls on ‘big’ weapons like the Executioner’s axe (Brutal 2), or intriguing, exciting experiences with weapons like the Mordenkrad (which rolls 2d6 – but both dice are Brutal 1).

There’s also the weapon group and proficiency type. Proficiency types push characters towards a certain general type of weapon based on their class’ background; rogues and fighters are likely to be familiar with most swords, for example, but clerics and druids aren’t. That means that you can gate access to things mechanically, which you can use to set the tone for some characters. Shamans and druids use clubs and staffs and spears, which aren’t that good as pure weapons, but it’s okay, because they’re not as likely to need them. If a player wants to reach out of their proficiency group, that’s fine too.

Finally, there’s the weapon groups – that is, the kinds of weapons these things are, what they’re like, and what they do. In older D&D editions, there was a trend towards trying to put a weapon in a big group (simple, martial, exotic) and that’s it; special training may refer to a specific weapon, but then you got weird things like how the Bladesinger would refer to a character using a longsword or rapier or elven rapier. Instead, in this case, weapons fit into general groups, and weapon styles or feats can refer to doing attacks with types of weapons. Most interestingly, weapons can have multiple groups – so if you build a character who can do things with polearms and things with axes, a weapon that is a polearm axe represents an intriguing opportunity to do both.

These are good properties because the mean that the experience of using these weapons is qualitatively different than in other systems. You set the weapon up, and then you use it – Notably, there are a lot of things these weapon properties don’t ask you to do.

- They don’t include a lot of memory issues

- They don’t ask you to commit within the action economy

- They can handle choices made during the attack, like versatile

- They don’t want to be too specific

There aren’t any weapons that have a unique property; none of these weapons have a unique mechanic. That means a weapon property wants to exist on at least two weapons. That’s good – that suggests any weapon property invented needs to be made with a mind to being reused. Anything too specific probably doesn’t want to belong here.

Next time, we’ll talk about how these two idea spaces interact.

Hunter’s Dreams – Trick Weapons, Part 1

I started work on Hunter’s Dream back in January, with the basic idea being a way to play a Bloodborne style game set using 4th Edition D&D. The reasons are pretty easy to grapple with – starting with ‘I like it’ and moving on to ‘Bloodborne’s play experience is a tactical game of resource expenditure, not a story game of improvisation.’

Still, 4th edition D&D is a game of systems, and that means when you want to put something in the systems, you want to put in some rules. In Bloodborne, the trick weapons are a big part of the tactical experience, and they make the game feel that particular steampunky way. How then, do we bring that feeling into 4th ed D&D.

When looking at implementing these trick weapons in 4E, we want to consider what they do and how they do it. That sounds like basic stuff, but those questions are going to illustrate the difference between the two types of games and how I can make something that feels right in a different game.

Trick weapons in Bloodborne are weapons; you use them to attack opponents, destroy objects, and occasionally interact with environments in surprising ways – think about the times you cut a rope or knock down a hanging treasure. Broadly speaking though, the trick weapons are weapons, which you use to hurt people.

When you use them, you can change them from one form to another. Now here is where we can get a bit McLuahnish, and point out that medium and messages intertwine. See, Bloodborne is a videogame, and you play it with a controller. That controller has a number of buttons, and you, as a player, are expected to track maybe about seven to eight of those buttons at a time in combat. That means any mechanic you introduce, if it’s going to happen in combat, needs a button, and it needs a reliable button, because this combat is pretty high stakes. The game design is also what I call ‘fixed animation’ length – that is, when you commit to an action, you’re often stuck with it, and unlikely to be able to assert control over it along the way.

Following that, then, is that the trick weapons need to be weapons where your ‘trick’ doesn’t take a lot of buttons or fine customising. If you do those things, it’d take more time, and that might make it too inconvenient. With only limited inputs, then, the Bloodborne trick weapons are very binary. They’re either ‘on’ or ‘off’ – and you can swap them between one thing or the other in-combat. There are a few oddballs, of course, but generally, these weapons exist in form A or B, and in combat, shifting from A to B or vice versa results in a special attack.

Most of these weapons change in ways that reflect the technology of the setting. For some, the change is a big physical object shift; for others it’s turning on a special ability for the next hit. The weapons can’t be ‘normal’ weapons, even if they mostly resemble them – swords that become hammers, axes that become polearms, that kind of thing.

These two states want to be qualitatively different, in the context of Bloodborne; you’ll sometimes get different damage types, different speeds of attack, and different reach. In this game, those are very small spaces. Attack speed can be fractions of a second; Reach can be important down to similarly small units of distance.

To summarise:

- Bloodborne trick weapons are weapons

- They’re primarily used to hurt people and interact with the environment

- The trick of Bloodborne trick weapons is simple to use

- This differentiates them from conventional weapons

- There’s still room for mastery

- These weapons vary in how they attack

- Reach

- Speed

- Damage

- Special effects

This is our outline, the parameters we want to consider. Next time we’ll look at the challenges of setting this up in 4ed D&D.

4th Edition’s Space Problem

Normally you’ll hear me be pretty positive about 4th Edition D&D. I’m a strident defender of the game, which is made easiest by a number of the complaints about the game being entirely fake. It’s easy to be a righteous defender of something against blatant lies.

Still, there are flaws with 4th Edition D&D, which shouldn’t be any kind of surprise and yet here we are. Let’s talk about one of them. Heck, let’s talk about a big problem, and it’s a problem that’s structural. It’s so structural it doesn’t even relate to a specific class, as much as it relates to the way that classes get made.

Classes take up too much space.

Project: Hunter’s Dreams

The Pitch: It’s a 4th Edition D&D Setting/Modbook which is about playing Bloodborne and Castlevania style gothic horror hunters. Combat is not about crawling through dungeons and parselling out careful resources, but instead about short tactical fights of 2-3 sequences of fights in a row, known as Hunts, usually with solo-class enemies rather than larger groups.

Between each hunt, the players invest effort into the thing that forms the core of their group, their Nexus, determined by the type of group they are. You can build your own keep or workshop, or network of connected hunters, depending on the type of game you choose to play.

The aim would be to keep the tactical, movement-based miniatures-driven combat of 4th Edition D&D, and giving you a sort of ‘boss rush’ way of playing. DMs don’t need to design larger dungeons, but rather just small connected places for the hunt to find their prey, and thanks to the hunters being hunters, these encounters naturally can take the shape of kill-boxes, or containment points.

Details

This would be a gamebook, first and foremost; a single book that’s designed to work with Dungeons & Dragons 4th Edition. Hypothetically, if your players are into other systems, it might be designed to handle that kind of cross-compatibility, but the basic point is to be a game system for a game I like. The game would then be made up of a series of modules that you snap together to make your campaign.

One module would be the rules for creating your Nexus. A Nexus sets some ground rules for the style of campaign you play in and also works against the ‘murderhobo’ problem that more free-moving campaigns have. A Nexus is something that roots you back to a space – things and people you can’t leave, and it’d have systems for checking on or recognising the nature of the location the Nexus is in. You’d decide at the start of the game if you want to control one of three options:

- A Keep. Your hunters are known and important, and they have to manage and marshall the resources of the town. They may rule the town, literally, and they go out and hunt to push back the boundaries of dark around the town. This is for your more basic ‘heroic fantasy’ feeling, and have a system for managing competing needs in the keep. Think of it as being an anti-dracula, or princesses defending their castle. People like princesses right.

- A Workshop. Your hunters are part of an organisation within a city, and they relate to the people who live and move in that city. They can be trusted or distrusted, liked or disliked, and the central establishment of the workshop means they can benefit from the connected resources of the city. Workshop games are more like your Bloodborne, where people might recognise that you are a hunter, not necessarily that that means they should respect you.

- A Secret. Your hunters don’t have any physical location that they centrally can meet at. They’re all people aware of a secret of the world, and that means in their city or town, they’re the ones who can understand what the monsters are here for. This is for your Buffyverse kind of hunters, though set in a more gothic horror setting. In this situation, inspecting the monsters and hunting them may be seen as foolish or dangerous. There may be no idea of ‘a hunter’ and part of the challenge of The Hunt is making sure you can gather your friends together in time.

One module would be about dealing with monsters and classifying them based on their grouping. Back in Ravenloft there was the mechanics of Fear, Horror and Madness, which kind of did a similar thing – in this case, the idea is that monsters represent types, and exposure to/interaction with a type can change how you react/treat them. This would be a space for ideas like beasthood or maybe insight from Bloodborne. If players want to contain the powers of the nightmares, this is where I’d put that kind of idea.

Another module would be for handling gear. The 4th ed weapon system is really good for things like transforming/trick weapons, or weapons that evolve naturally over time. Your Nexus might be able to replace a conventional gear system – with gear and abilities levelling up based on a budget/availability. One of the funny things with 4ed is that most gear was just meant to get replaced by level – you were never meant to plow your entire budget into a thing that you could hypothetically pay for, after all. Just making it so ‘downtime can be spent to upgrade gear’ seems an obvious way to streamline gear and reduce the quantity of knick-knacks that are a bit of a design problem.

Another module would be for ‘Races.’ Particularly, it might be useful to make a system for turning a lot of Races into Ancestries or Heritages, the idea that in this culture, what a Dwarf represents mechanically is just another type of human, and to put the races that are blatantly visually monstrous in a basket that let players play twisted, monstrous hunters. Imagine being a minotaur trying to hide in Yarnham.

Needs

Playtesting, for a start. It’s also a big project. Art for RPG books is always a thing. Fortunately, this is something I’m going to want to exist so I can run it, so that’s going to mean that even if it never gets made/polished and sold as a big project, this guide will still be useful as a reference point if I share development on this blog!

What’s Nyarr?

Hey, what have I been up to these past few days? Well, I was writing up the Nyarr.

What’s a Nyarr?

The Nyarr are going to be this June’s tabletop release. They’re not going to be a card game – they’re a new ancestry for your tabletop RPGs, released as my Lost Libram line of content. Lost Libram is my division of my work that’s from my older D&D work, stuff I never released because hey, 4ed came out and my friends are playing that now.

As a designer, I still love this old content, and realising there’s a market for it, I decided I wanted to get it out there. Especially since a lot of writing of this type isn’t mechanical, it’s conceptual, it’s giving flavour and tone for the stuff I’m sharing. RPG writing is in a lot of ways bits that you playtest.

Here’s an excerpt:

Nyarr are humanoids comparable in size to humans, ranging between 150 cm (5 feet) and 195 cm (6-½ feet) tall. Despite their size though they are markedly heavier than humans, ranging from 72 kg (160 lbs) to 118 kg (260 lbs). Nyarr have skin hues that range from a dark brown to a pale green, and some Nyarr are coloured blue or purple. Nyarr have soft plates of chitin on their skin on their shoulders and knees, and their feet are split into two large forks, rather than five small toes. In silhouette, Nyarr are most like humans, though with larger feet and hands.

Nyarr are most easily distinguished from humans by a number of secondary traits; Nyarr have scaled hands with pronounced, thick fingernails that look like claws, scaly plates on their shoulders, horns – typically two, though rarely four, – long, thin tails, sometimes splitting with feet that stretch up into a ‘high’ stance for running. A Nyarr running tends to lean forward a great deal. These traits have been called ‘demonic’ and ‘monstrous’ commonly, though their actual threat is quite minor; the scales protect their hands for fine manipulation in extreme environments, and the horns and tail allow them to steer while running more readily in areas like cliffsides or desert plains.

Nyarr gender differentiation is complex to explain, as Nyarr have at least three major genders. Their words for each gender are translated as generally ‘male’, ‘female’ and ‘onyar’. Physical differences between the genders are hard to determine; roughly half of Nyarr have a shape regarded by some students as ‘feminine’, but commonly-recognised indicators like hips and breasts are not common to the genders. While female Nyarr tend to have shapes other cultures regard as ‘feminine’, and male Nyarr tend to have shapes regarded as ‘masculine,’ these are not hard rules at all. Onyar Nyarr vary the most, with some onyar having prominently powerful arms and legs, with a more petite body trunk. Some Nyarr tribes even send out explorers to learn from other Nyarr other genders, trying to find the best ideas for their people to choose.

The Nyarr then, are a deliberately enby inclusive race of cool monster people for Dungeons and Dragons 3.5, who are powerfully social, deliberately cooperative, and inclined towards trying to make friends, even as they are careful about trusting the rest of the world for being hazardous to their culture at large. Visually they’re kind of like big-footed and big-handed Tieflings, and they have culturally, an idea of ‘choosing’ genders from their three major genders, with the understanding that some Nyarr choose other genders if they’ve heard of them.

One detail here, and which I’m putting out there to put on the record even if I fumble how I say it: I am recruiting non-cis artists and writers to contribute small bits to the text of this. My thinking on this is pretty simple: The Nyarr represent a way for a game player, someone who isn’t necessarily heavily connected to the world of nonbinary genders, to be introduced to them, and, as a creature in a game, it gives people a chance to play with, and come to understand that idea. If I’m going to put that kind of thing out there for people to include in their game, I’d want to make sure that people with experiences like the Nyarr interacting with other cultures, are able to put their mark on the work.

Complicating almost all relationships Nyarr have with other cultures is the expansionist trends of almost every non-Nyarr culture. Nyarr have a phrase that translates roughly as Be Wary Of Those People. In the past, Dwarves have hollowed out mountains that Nyarr considered home, collapsing the landscape underneath them. Humans have cleared forests they considered home and turned them to furniture and machinery. Elves have magically tamed jungles and ousted Nyarr from the trees they considered home, in the name of making them more like their own forests. Nyarr tend to view all these cultures as invasive.

Humans and dwarves are very much cultures that judge and compete, and view survival as a personal thing. Nyarr culture rejects these ideas, and sees survival as being a shared responsibility. Also the humourlessness and lack of fun in Dwarf culture is abhorrent to Nyarr outlooks – to survive without an ability to feel joy is to be as good as dead. Dwarves can sometimes appreciate Nyarr because of their survival abilities, while others see Nyarr and their culture of change and cooperation as weak and strange.

The cultures less prone to building empires and starting wars tend to cooperate with Nyarr better – particularly orcs, who rarely want territory that Nyarr alone can hold. Nyarr feel a kinship with the half-humans like the Half-Elf and Half-Orc, seeing them as something a bit like themselves; outsiders in a group.

It’s a little ostentatious, I guess, but I want to be careful about the ethics of it. I don’t want to stomp into gaming with Here Is A Trans Metaphor For You, As Expressed By Me, A Cis.

If you’re at all interested in this, if you’d like to give the Nyarr a read before their release, let me know. I don’t pretend to be an expert, and I can’t really afford a proper high-grade sensitivity reader, but if you’re curious, let me know.

4ed Problems: Splintering, Part 2

Yesterday, we talked about how long the lifespan of 4ed D&D was, and we talked about how, it was good, actually. Our framework was, basically, that players had expectations of classes, and we named the problem of splintering.

When you built a character in 4ed D&D, you might be startled by how many feats you got. Every even level you got a new feat, and you started with one as well – meaning a character wound up with sixteen feats. This meant that the game had a reason to make up lots of feats, and that was where the game offloaded a lot of mechanical responsibility – rather than making tons of variant rules for how your classes changed as you levelled up, most of them gave you a starting package, and you could use feats to unlock the bits of it you wanted.

This was true of races as well, by the way – in the Monster Manual there were a handful of extra races just starting out, but none of those races had any feat support, unlike the Players Handbook races, and that meant those races were always permanently underpowered. Making a race or a class was not just making powers – it was also making feat support.

There were other places feats did the heavy lifting the system needed done, like the ‘feat tax’ feats like Expertises and Defence feats. The game math was curved, so as you got to higher and higher levels, the enemies assumed your ability to hit them wasn’t just improving linearly, and the same for their ability to hit you. This meant there were two feat families you just kinda assumed you’d get.