Game Design Is Interface Design (Mostly)

Hey, what’s interface design? it’s the discipline of designing interfaces. Shocking. Marvelous. Hilarious. I should be in the pictures. But let’s keep going since that doesn’t clean everything up.

Continue Reading →3.5 Memories: Worse Than The Fighter

In Dungeons & Dragons 3.5th Edition, a thing that’s not at all un-awkward to say, there was a set of hardbound expansion books released as a group to satisfy groupings of characters as an archetype. The first set of these, released around 2003, were The Complete Divine, The Complete Arcane and The Complete Warrior, a trio of books that kind of told you what they were about in the name. You had arcane spellcasters, divine spellcasters, and uh, everyone else, I guess.

The Complete Warrior had to bear up as the space for all the classes that weren’t divine spellcasters (but the ranger and paladin can play here too, sure) and all the characters who weren’t arcane spellcasters (but there’s stuff in here for melee spellcasters). Barbarians and Rogues and Monks all got to cram in on this book, but based on the name and the style, and of course, the preponderance of feats in this book, this is the book that’s for fighters.

It’s also a pretty cool book, if you’re looking at the good stuff in it that you want to use and make sure people can use. LIke this book has tactical feats, a category of feat that kind of roll together a small number of ‘not enough for a full feat’ advantages into a single grouping, and that’s a really good way to expand expertise on fighters. Prestige classes in this book include the Actually Good Frenzied Berserker, the kinda decent Tattooed Monk, the sorta-maybe-why-not War Chanter, the busted as hell Warshaper and that’s four classes worth having access to in most campaigns. The excellent Combat Brute tactical feat is in here, and uh

Anyway, the point is this book is one of the books I think of pretty positively.

It’s also a book that features the rare examples of a class actively worse than the Fighter.

The ‘Samurai.’

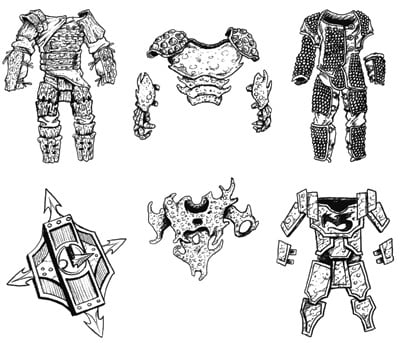

The Immaterial Material: D&D’s Stuff

You know for all that D&D is seen as a story of heroic fantasy it’s awfully bitsy. I don’t just mean the way that D&D is a game that encourages a truly remarkable amount of special acquisition of items for play – how many people do you know who have a miniature for their characters? – I mean that the story that plays out in the game winds up being about stuff. Lots and lots of stuff.

I’ve been writing about ‘stuff’ in games lately, reading about how we treat material objects, and while there’s definitely a different kind of materiality when you talk about a playing card, a dice and a meeple versus the text on a page that reads +3 longsword, there’s still something to be said about the way that D&D, 3.5 and 4e especially (because those are the editions I know) focus characters over an inevitable wardrobe full of stuff.

Now, there’s a reason for this, and it gets at one of the basic assumptions of the game that D&D wants to be. D&D ostensibly is a game about heroic fantasy, but connected to the idea of this heroic fantasy is a need for adventurers to be mostly, heroically empowered but still fundamentally scaled heroes that can be compared to normal people. It’s not the X-Men, it’s a place where your hero who swings a sword can’t be expected to cut through the bars of a prison, but if that sword was magical, then they could.

Now, this isn’t a bad thing per se, but it does tell you something of the basic assumptions of a world like Dungeons & Dragons and it’s a basic assumption that I’m used to seeing in a lot of, of all things, first person shooters. Yes, I’m probably going to talk about DOOM again, maybe.

When you start to talk about what stuff is used for in D&D, it’s pretty easy to see that stuff can do a lot more than people can do. People are limited, they’re made of meat, and they’re not capable of long-lasting, permanent effects. Even the wizard has to spend spell slots to fly, but a pair of winged boots will take you into the air as long as you like. The boots are expensive, and that’s another element (the relentless roll of capitalism).

One other thing is that items can be systematised, because objects, we believe, behave consistently and repeatedly. Despite the fact that the D&D world is typically represented as pre-industrial (except the good ones), these items are made and represented as if they are in their own ways kind of mass-produced; a jagged fullblade from one continent will work the same as a jagged fullblade from another.

This is another funny detail about this worldview: The items you’re building and examining are being treated as if they’re just making a thing that can exist; it’s not a matter of someone choosing to create something to overcome a task or have an effect (and indeed, if you approach a DM with a specific request for an item function that isn’t from the existing ruleset, that can be seen as asking for something ‘too specific’). It’s not that you made a weapon that does more damage when it hits an opponent in a vulnerable moment – it’s that you made a jagged or vorpal weapon, and those existing elements have math to them.

Stuff gets to be consistent! Stuff gets to work, and keep on working! We live in a world full of machines that work consistently until broken, and it seems that that plays into how we want magical devices to work in D&D. We don’t find that unrealistic, that a character can wander around in a small town’s economy’s worth of super-specialised consumer goods that literally nobody non-Adventurey could afford to meaningfully buy, we don’t find it unrealistic that these objects can be somehow mass produced and we don’t find it odd that these things can do much more than a person can do, because we accept that it’s okay for objects to do these things…

… and that it’s not acceptable for people.

This plays into the way that the worlds of D&D are made, by the way. Not only are places like the Realms and Eberron full of underground caches full of fantastically expensive and yet still practically useful antique hardware, they’re also places that mysteriously have investors and traders who can be bothered making these goods and trying to sell them on despite their fantastically obvious market problems.

This relationship to stuff is one of the things that breaks easily when you start trying to use D&D for other stuff. Infamously, the game D20 Modern tries to dispense with the relationship to stuff, making mose equipment mundane and focusing the game instead around the ‘wealth check’ that gave you a general idea of what you were capable of buying. The result was that your stuff suddenly didn’t feel like it mattered, but your character never mattered as much as their stuff – so you mostly spent your time piloting around a pair of guns and a skill list.

Making Draft Complicated To Simplify Draft

You know drafting games? I like drafting games. Magic: The Gathering is a drafting game, and it’s really good at it. You draft a deck, then spend some time playing that deck, and that’s fun. We made LFG, a single box card game where you draft a group of heroes to go on an adventure, adventure pending.

Draft is very appealing to me as a designer because it has some virtues like simultaneous turns, and it inherently presents players with choices. Drafting is often used as a component in games, but the drafting itself can be really exciting. Drafting does have problems though, like you need a number of cards and players to make those choices interesting. If you’re drafting, say, four cards between two people, thoes choices need to be extremely difficult to make that interesting, and when you do that, you have a really small number of cards and therefore the game has only so many ways it can be replayed, and that’s risky. I have made games that don’t replay well on purpose, or games with incredibly hard choices that can feel dreadfully unfair (hi, You Can’t Win), but those are hard, thorny games for people who like challenges, and they’re also really small.

There’s also a mastery depth problem when it comes to draft. If you know the most cards, if you remember the cards that are going to be in the pool and potential application with other cards, you’re going to make the player with the largest amount of possible information and the best understanding of ways the game can fork be the player who has the most chance to win, and that’s not great for getting new players involved.

With that in mind for a small card game I’m working on at the moment (one of our $15 range), which is going to be about recruiting your own group of superheroes, I’ve come up with a new drafting technique I want to share.

- Deal out all the cards to each player not as a hand, but as a deck. So the player gets their cards, and they don’t look at them and don’t know what they’re going to do.

- Set these decks between each player – I’m right handed so when I do this test I intuitively put it to my left, so the player on my left can reach it.

- The drafting begins. Each player draws two cards from their deck, chooses to keep one of them, and puts the other card on the top of the next player’s deck.

- Repeat step 3 until the decks are only one card.

This means that players still have some specific choices; you know what you’re handing to the next player, but you don’t know all the choices they have. You have to choose between two cards each time, rather than have to manage seven then six then five and so on. Also, you don’t have the chance to determine, at the first draw, everything that you’re going to do, other people’s strategies based on what you’re passing. You’re presented with much more limited information. The draft unfolds a little more, without being all presented up front.

Making Magic (In Games)

Now, I’ve talked about magic and cards this month and I’ve even talked about how hard it is to find games that are properly about magic as much as they’re about single-attempt tricks, conning the rules of magic like in Simon the Sorcerer and the like. What I haven’t really been able to grapple with – and don’t hate me for my lack of time to dedicate to random exploratory design right now – is how hard it is to represent doing magic in one of my games?

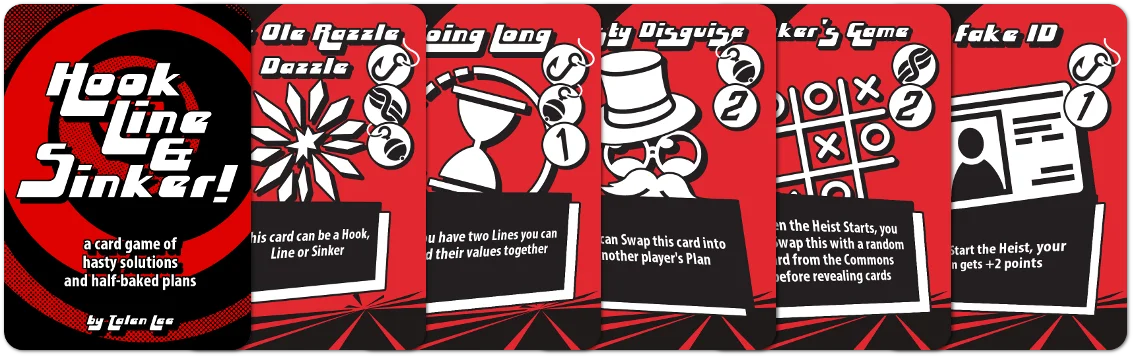

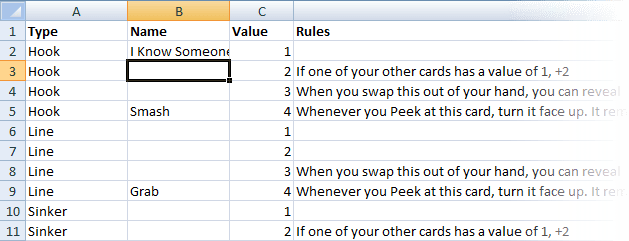

I’m torn on it! Because I’ve certainly played with similar principles. One example is Hook, Line, & Sinker, a game I made earlier this year. It even references specific card tricks and confidence tricks, things from that same mangled tangle of lies and facts and half-histories.

Now, something Hook Line & Sinker does that I do like is that it represents a con as a three-stage act where knowing the pieces and executing on it properly is the challenge. It’s not a matter of getting lucky, it’s a matter of proper execution of a plan of related pieces. Great. Easy!

It doesn’t necessarily work as a magic game, though, because part of what’s going on in this game is you don’t really know what parts you have to work with. It’s impromptu planning, but that’s con artists and fast-talking criminals, not the work of the magician, who has to work over and over and over again.

Normally when I think about a theme, I tend to think about mechanics I know, like a library of things I can do, and I keep coming up empty for good mechanics that ‘feel’ like magic. I’ve tried a bunch of options, and here’s what I got so far:

- Probably no dice. Dice give you a good random generator, but part of the point of what I like about magic is how it’s about practice and execution.

- It might be a duel game or co-op game, because I can’t quite work out how to make magicians compete with one another except in the creation of tricks and showing off

- Magic is a matter of using classic parts and imagining new props or designs so it needs to be a game with some degree of creativity

- But part of that creativity needs to be exciting or interesting, so the parts can integrate cleverly or the players can ‘show off’ what they did.

This is hard stuff! The one thing I keep coming back to is this might be a solo game about learning a routine and eventually perfecting it, building on Friedemann Friese’s fun little card-rotatey deck-builder game Friday.

For now, I don’t have a great idea. I haven’t made a lot of solo games yet.

Still, we get better at things and we come up with solutions by spending time with them, and thinking about them. Maybe you’ll see me come back to this. Part of what you come here for is to watch me make games, and this is one of the things that sometimes happens. I hit a wall.

Making Hook Line Sinker

Hey, check this out.

This is what I call the cover card for our game Hook, Line & Sinker. At the time of writing this, I’m still testing this game, but I like this aesthetic for the game, and unless it tests badly for use, it’s probably going to stay this way.

I made this. This is my art. I’m really happy with how it looks, and I figured I’d like to show the process I went through to make this card, this specific card. Below the fold, then, is a step-by-step process of showing how I made this, and this is very close to my first look. This was all done with like, basic tools that you can find in most every graphics program.

Making Fun: Years Later

Starting in November 2017, I decided that, with enough attempts made to explore methods of how, that I would start uploading videos to Youtube. I decided to build on my then-recently-finished Honours thesis as an experiment in seeing what I could create that could suit a rapid-fire fast-talking Youtube content form, and as a direct result, my first video series, Making Fun was made.

It’s been a bit over a full year now, and I thought I’d spend some time to look at these videos and see what I thought of them, what lessons I had learned, and what lessons I would recommend.

Top Dog

Games are filled with opportunity for discovery. When you’re exploring a device with low stakes, you are in that time, playing with it – seeing the boundaries of what it allows. It is the play of a gear, more than the play of an actor. Play is how we find the limits of things.

Okay, rewind. A story. A story of a specific thing in a specific place.

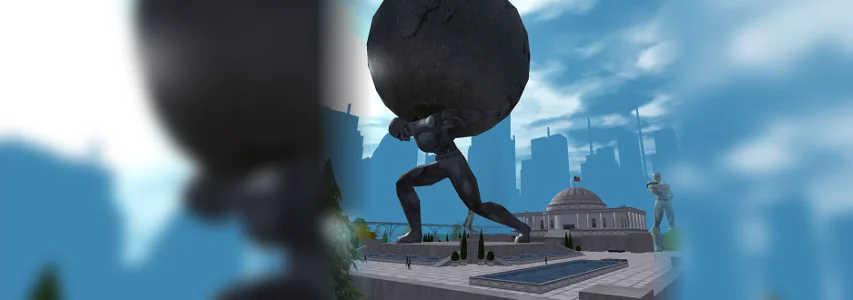

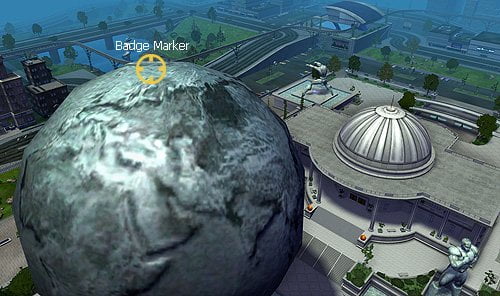

Back in the day, in City of Heroes, when you first made a character, you’d complete a short little tutorial, and be dropped in front of the steps of the Atlas Statue in Atlas Park. It looked like this.

It’s a common thing for players to talk about, the first moment the got a flight-related travel power. It was usually hover, but sometimes it was a jetpack. However you did it, when new players gained the ability to leave the ground, one of the most common things they’d do is use that power to fly up to the top of the Atlas Statue and look at what was there.

What was up there was an exploration badge.

These badges were a bit like achievements. You could put a badge on your character and it’d display under your name. More important than what this badge could do, though, is what this badge did.

When you explore, one of the most disappointing things to find is nothing. I have memories of struggling up mountains in World of Warcraft and New Vegas and finding blank textures and no reaction to my presence, a sign that I hadn’t actually achieved something difficult but just had done something the developers had never expected. That taught me to stop trying those things, to stick to the path, to give up on exploration and excitement. I turned the gear all the way in one direction, and the game didn’t react well to it, suggesting I never do that again.

In City of Heroes, you tried something, and the game found you when you got there, and said hey, yeah. This kind of thing works.

The Top Dog badge encouraged players from the earliest point to always look on top of things, around things, to think in terms of what counts as worth exploring. It was a good idea, and I think that it rewarded players for being playful with the world.

Blocking out a Card

Hey, here’s a thing I was working on in February. You may have seen it on twitter.

Here’s a cut link because this is going to show full images of cards and those things are loooong. Oh and pre-emptively, these cards have been munged by Twitter because I could not be hecked to re-export these progress shots.

Form Informs Function

I’m looking at this game, Yamatai.

It’s this big, bulky beast of cardboard, a real classic Euro of dear god, there are how many bits? At its root, it’s a game of laying paths and fulfilling economic requirements. In fact, you can almost punctuate Yamatai as a sentence with a lot of asterisks – you place boats* on a map* to fulfill goals* that earn money* to build structures* to earn victory points*. And every single * indicates a place where the game has a specifically designed system meant to make that particular action more complicated.

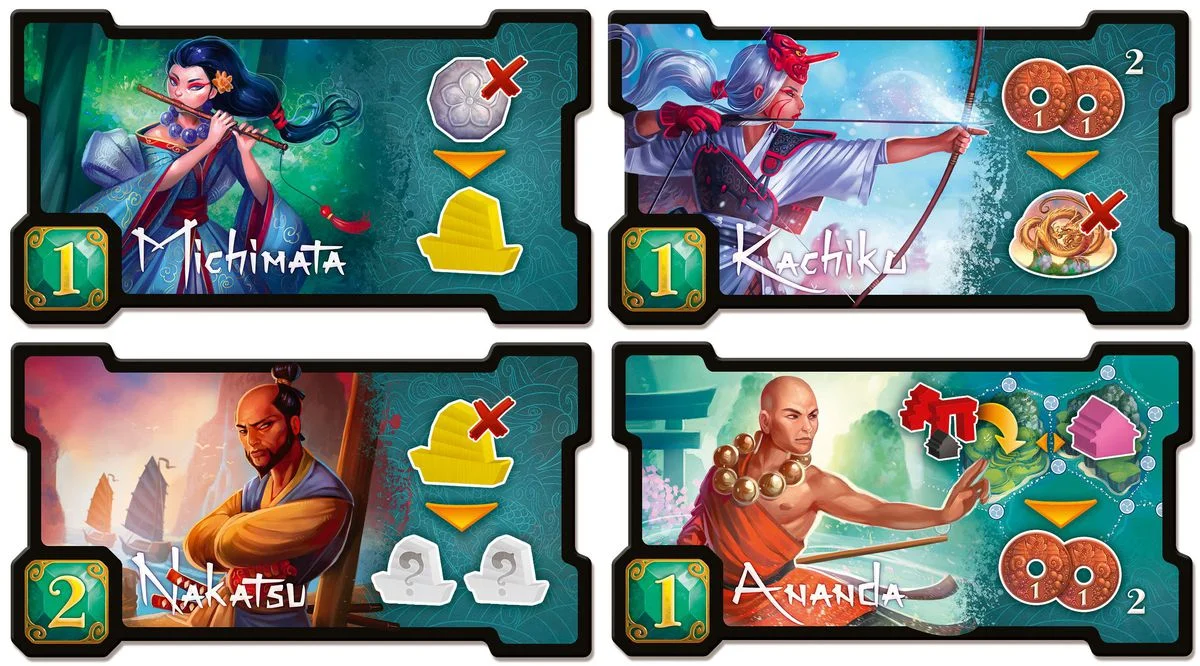

If you remember me talking about alignment systems as plumbing, then this is the kind of game where you work with a lot of plumbing to make it work. It isn’t a bad idea, most games are simple systems rendered difficult by complications after all, Bernard Suits and the willing overcoming of optional difficulties and what not, but anyway, in this game, there are these tiles that determine special game actions you can take and how fancy your faction is regarded, known as Specialists. They look like this:  This is how they actually look. They have these names. The rulebooks specify what they do, but never who they are, and while we can talk for a bit about mechanics informing character, it does feel a bit like a swizz to turn these people into these tiles that represent actions. These people aren’t reduced to what the can do, they’re reduced to one action only, which is good for a big and complicated game that already has too many bits going on.

This is how they actually look. They have these names. The rulebooks specify what they do, but never who they are, and while we can talk for a bit about mechanics informing character, it does feel a bit like a swizz to turn these people into these tiles that represent actions. These people aren’t reduced to what the can do, they’re reduced to one action only, which is good for a big and complicated game that already has too many bits going on.

Why are they people, though?

These could be machines, or flags, or they could be brokered trade details (and maybe even decorated to look like them) or faction histories or – there are lots of things these tiles could be. They’re not. They’re people. They’re named like they’re people.

To spin this around to one of my own designs, I’m working on this small game (at the moment – it’s probably long done by the time this goes up) where there are only eighteen cards, and they each represent parts of a plan. What’s tripping me up at the moment, though, is the challenge of what verb form to put the card names in.

I’m not trying to bag on Yamatai (here) for reducing Asian People To Objects (again, here). I’m thinking about the ways we talk about mechanical objects and their purposes. How we choose them. How to make them consistant.

Janet Murray once expanded Caillois’ model of gameplay with its agon and alea and mimicry and ilinx and described a form that Caillois hadn’t considered, of rhythmos. Her idea was that some forms of rules satisfaction came from making rules that worked cleanly together as rules, and that helped drive gameplay. This is a very real effect, and one that you’ll notice if you miss it.

And so, here I am, up late, worrying away, like a beaver at a twig, thinking about conjugation and the card-tile non-people of Yamatai.

4th Edition’s Space Problem

Normally you’ll hear me be pretty positive about 4th Edition D&D. I’m a strident defender of the game, which is made easiest by a number of the complaints about the game being entirely fake. It’s easy to be a righteous defender of something against blatant lies.

Still, there are flaws with 4th Edition D&D, which shouldn’t be any kind of surprise and yet here we are. Let’s talk about one of them. Heck, let’s talk about a big problem, and it’s a problem that’s structural. It’s so structural it doesn’t even relate to a specific class, as much as it relates to the way that classes get made.

Classes take up too much space.

Battlemind Woes

At the time this post goes up, I will have already played this year’s Weekend D&D game. If things went as I expected, I’d have played a Battlemind, modelled on Gilgamesh from Fate: Grand Order, in that he’s a reckless garbage boy, a property-rights-confused wanna-be Hero of the Sands of a half-Gerudo.

This has meant looking at the class the Battlemind at some length, and let me tell ya, it ain’t great.

For those of you not familiar with 4th Edition D&D, here’s the basics: The Battlemind is a defender class, meaning that in combat, it wants to spend its time forcing enemies to prioritise it – it’s a form of control. The defender wants to make enemy actions as fruitless as possible by making those actions directing attacks at someone who can best handle it, and does this by being the toughest person on the field and then making it hard for enemies to attack other people.

A Good F**king Idea

For christmas last year, my sister got me a copy of F**k, the game. On the most surface level, this game isn’t one that interested me – it’s basically a party game, in that particular character of a game where you don’t have to pay much attention and it’s not super important how well you play. Plus, a plain white box with stark san-serif fonts always makes me think of Cards Against Humanity, a game I definitely don’t want. This meant I never really investigated F**k.

When I got the game, I did a quick investigation, and in a game designer way, it wasn’t actually very hard to put it together. The game is a stroop effect engine, and then includes a bit of spice in the form of Snap-like mechanics. You have cards you’re trying to get rid of, and getting rid of them involves not making mistakes – then the cards try to make you make mistakes.

The Reunion: Setup Mechanic

Here’s the idea: Players sit down and assume the roles of actors reuniting after years apart, who used to work together on a successful, formulaic sitcom. After the sitcom, one member of the cast had a very successful career while everyone else did not – the ‘Star’ of the game.

The mechanic that sets this game up is that each player gets a card indicating their role and the degree of fame they have. Then, starting with the player with the highest value card, players close their eyes – meaning that the player with the highest value card has no idea about how anyone else’s career went, but everyone else can see the people who had more successful careers than they did.

This one-way information is meant to play into the game, because the sitcom was a mess behind the scenes. And the hopeful aim of the game is to create a short story, told in flashback, about what the sitcom was like, about what’d happened since, and about the kind of people they were, all told by the oblivious Star piecing together the narrative of what happened to a life that had nothing to do with them.

The obvious inspiration for The Reunion was Bojack Horseman, which has a lot to say about the way TV comedy gets made. The thing is, the stories of how TV series were made are all so full of extremely strange stories where so many things go wrong, where you can change or replace any given incident and you’d still have a distinct story.

Now, this central mechanic, where there’s a pyramid of knowledge, excites me because it’s a fun puzzle. One player has to start putting together four or five secrets from the things they can be told, while the other players are trying to tell their parts of a story without breaking character. At the same time, though, this isn’t guided – it’s not like Dog Bear where there’s someone in charge of the game who can be told to steer the game to an actual story point.

The really scary thing to me about this game idea is how do I keep it from getting Content Warningy? The whole point is to give players some reign to create, ideally something ridiculous and hyperbolic, but also with a dark twist as to what things were really like. And when you give people a set of prompts about the failures of a creative process, there’s always this part of me that worries people will take it to a really dark space.

In Dog Bear, there’s not just the Boss guiding the game who I can directly entrust with the authority to keep players from being assholes, but it’s also comically ridiculous, with its cyberetch and nanomachines. Not the same thing here. And now, these are the constraints that the design needs to overcome.

Getting Around The Ocean

One thing I wanna do more of this year on this blog is talking about design. Particularly, I want to talk about things I learned in my three years of monthly games. I want to make sure that information lives here on a blog, a searchable data point, rather than in a notebook with an index and a scribbled number.

I’m doing this, because I want you to know what I’m doing. I’ve done a bit of stuff about the graphic design techniques I use, and I’ll try and keep those up. But I’m also going to try and talk more about decisions, the actual plans involved.

Okay, with that in mind, gunna start on this. Design is the process of making choices to achieve outcomes within constraints.

One of my constraints at the moment is the Pacific Ocean.

If I want to print a game, DriveThruCards asks me to order at least 1 copy before I can sell it on their storefront. They have to print it, then send it to me, a process that takes a few weeks. If I want to change anything, I have to print another copy, and get that sent. This means that a small revision can add two weeks to a work and a large revision can add six or so. This can also mean that sometimes I’ll have to stock up on a game, and realise it’s got a mistake in it after the fact and then I’m left with goods that just fail in some way. This can be a real bummer!

This is definitely a local thing. If you’re in America, the costs are much lower, and the wait times aren’t so bad.

This has me thinking more about digital distribution of goods. Things I can send to people digitally, or small products, are a good idea. Right now, the most basic ideas I can see here are what I consider booklet games, where a small booklet (and maybe some extra things like dice or playing cards) is all you need to play. Another option is RPG Supplements – things like classes, ancestries, equipment or whatnot for various tabletop game systems I like and use. Another option is print and play, which… well, last year I meant to do experiments in that, and I didn’t get around to sharing much about it.

The final option, which is a bit more ambitious, is the idea of an expanding supplement game. A game that starts with maybe 10-15 cards as a print-and-play; and then month to month, I start adding more to the print-and-play, until it culminates with a large, final design and visual aesthetic. This sounds really exciting especially if people invested in it get to request/suggest specific card ideas, and see their ideas implemented!

These are some ideas.

For now I think I’m going to try and talk more about the process of finishing up betas for Adventure Town, then the project currently called The Reunion. The Reunion is an improv game, a single-session RPG which can have a storyteller or not, based around the players all being actors coming together to reunite after their most successful show has ended, inspired by Bojack Horseman and a hidden-identity mechanic I cannot escape thinking about.