Gdcn’t #3 — You Don’t Know Apples

This week, from the 18th to the 22nd of March, it’s the Game Developer’s Conference. This is an event in which Game Developers from across the industry give talks and presentations on what they do and how they do it to their peer group. In honour of this, I’m presenting articles this week that seek to summarise and explain some academic concepts from my own readings to a general audience. In deference to my supervisor, I am also trying to avoid writing with italics in these articles outside of titles and cites.

How do you know what an apple is?

And do you need to know what an apple is to talk about what an apple is?

Continue Reading →Gdcn’t #2 — Incomplete Authorship

This week, from the 18th to the 22nd of March, it’s the Game Developer’s Conference. This is an event in which Game Developers from across the industry give talks and presentations on what they do and how they do it to their peer group. In honour of this, I’m presenting articles this week that seek to summarise and explain some academic concepts from my own readings to a general audience. In deference to my supervisor, I am also trying to avoid writing with italics in these articles outside of titles and cites.

Have you ever heard of this Foucault guy?

Continue Reading →Gdcn’t #1 — Understanding Others

This week, from the 18th to the 22nd of March, it’s the Game Developer’s Conference. This is an event in which Game Developers from across the industry give talks and presentations on what they do and how they do it to their peer group. In honour of this, I’m presenting articles this week that seek to summarise and explain some academic concepts from my own readings to a general audience. In deference to my supervisor, I am also trying to avoid writing with italics in these articles outside of titles and cites.

There’s an association with academic reading that fundamentally, academic writing and thinking is about a disconnected experience of reality that is explicitly not practical or realistic. ‘An Academic Point’ is a term we use to describe a thing that isn’t connected to any kind of realistic experience. I want however to talk to you about an idea from academia that gave me words to describe something I found important for living my life and being a better person. It’s an idea, it’s a tool, it’s a pitfall, and it is, importantly, a story.

It is a story that starts with the technique I use in my research called ‘autoethnography.’

Continue Reading →Playing For Money

Hey if a game is the consensual overcoming of unnecessary obstacles, are people still playing a game if they’re being paid to play?

What if the game does not have money as part of the game?

What if being seen as playing the game is incentivised?

Is capitalism fundamentally violent?

Sure let’s start it off with some easy questions.

Continue Reading →Y’know What, I’m Fond of Donald Norman

Donald Norman is the author of a book called The Design Of Everyday Things, which came out in 1988, 2008, and 2013. It is a book that has been pored over and referenced and cited and reconsidered for all sorts of disciplines, many of which come up in my PhD literature review, which is why it’s on my mind, and one of the things that keeps coming up in that – two things, really – is that Donald Norman is pretty sweet and people don’t seem to do much to dilute that.

Continue Reading →The Man In The Memer

Hmm, is that a Michael Jackson reference too spicy to use. Not sure. Well, I’m sure my better judgment will kick in before I post this. Or maybe it won’t, because what I want to talk to about today is the idea of autoconnoisseurship.

Continue Reading →Justum Bellum Sidus: Making a Plan

One of the classes I teach is about the critical engagement with a videogame text (or paratext). One of the things we do in this subject is to engage with the class materials ourselves to show the students what’s involved. Basically, ‘hey, this is about engaging in something that interests us.’

I proposed, for my pitch, the idea of a video essay that examined the idea of just war in the videogame Starcraft 2. I picked Starcraft 2 as an example for a few reasons:

- It’s more recent than a lot of my videogame interests. It’s more contemporary to my students’ age group.

- It’s got a thriving esports scene, a real world paratextual surface, so there’s an element of the game to examine.

- It’s not something immediately obvious to me, so I’m not just cheating and answering a question I already know.

With that in mind, here’s a little audio of me thinking through my process for how I’d work on this project, in the early days.

The Magic Circle (The Magic Is Racism)

One of the few concepts from Games Studies that has escaped into the general atmosphere of people talking about it normally is the idea of the magic circle. The magic circle is an idea mentioned once in the book Homo Ludens by Johan Huizinga, which, much like other off-handed comments made by people focusing elsewhere, wound up becoming something that the games studies world spun off into a great big mess of noise, hi there Wittgenstein thanks for making ‘defining game’ into an academic sporting event.

But the magic circle ostensibly, as developed later by Roger Caillois (somewhat, even if he thought Huizinga was a bit stinky) and kind of elaborated on further by Ian Bogost (kinda?) is the notion that a game exists in a space created apart from the general real world; that the beginning of and experience of playing a game involves engaging in a shared separation of reality that everyone involved recognises and accepts has nothing to do with reality and can be therefore, a place for anything to happen.

Continue Reading →The Grasshopper’s Gotta Go Fast

One of the most common academic books you’re ever going to hear me mention, if you hang around me for any meaningful length of time, is going to be The Grasshopper: Life, Games and Utopia, and I’m not double checking the order of the terms in the title. It’s a book published first in 1978, by a guy called Bernard Suits, a lecturer from the University of Waterloo. The book is considered, now, fundamental to the philosophical consideration of games, and is the source of one of the most common definitions of games you’ll hear — indeed, the one I use to be maximally inclusive: A game is the voluntary attempt to overcome unnecessary obstacles.

If you’ve listened to me explaining games in any expansive way, you’ve absolutely heard me quote this. Maybe sometimes I’ll say consensual instead of voluntary and maybe you’ll see noncompulsory instead of unnecessary, or restructuring the sentence back to front in some other way. If you only learned one thing from the book, odds are good, it’s this definition, which is useful for a bunch of reasons. It gives you freedom, it’s very inclusive, and it also asserts that you can’t be forced to play, which I found very important to instill in those I teach, that if you’re not choosing to do it, you’re not playing.

It isn’t the only idea in the book, though.

Continue Reading →Decemberween 2022: NixiiiE

It’s another Nixie Posting!

Nixie is of course an influence on my work, partly because she’s my adorable disrepectful internet family, but also because this year has featured some super dope Nixie Content.

I’m not linking to twitter, because

uh

Twitter, right now.

But that’s okay because what Nixie has done this year that excites me the most is seizing the pedagogic means of production. What she’s been doing has included amongst other things, learning languages and that includes things like moving, something which sucks at the best of times.

But twice this year, Nixie has come to me to ask my help making a game. And then when I told her methods and tools I’d use, she did that thing that I always love to see: She went ‘okay, I got it,’ then she went and made the game to her specifications.

These games were then cool enough that she showed them to her teachers and those teachers went and told the class about them.

Twice this year, I’ve watched live-streamed performances of Nixie at choir. One of them was because she wanted me to save a video for her, and one of them was because, well… it was her recital. It was a choir performance she did, and she invited me to come watch, so I woke up and sat back and changed my day’s plans to make sure I was there to talk to her about it.

Is it weird to say I was proud of her? I know I clapped at my computer. That seems weird. Oh well.

Now of course, you already knew I think Nixie is great and adorable and sweet and definitely cool. And I’m really laying it on thick here just so I can bully her with reminding her of how wonderful she is. But the point is the longer this article is, the more of it she’ll have to read as she gets more and more annoyed at me.

See, she’s also a good writer, but without the threads to link to, I’m not about to be able to prove it. So that’s why this year, around when Twitter Looked Volatile, I made a cheeky little move to contact her and ask her to give some input to an article I was writing about one of her favourite movies, Air America.

And then, to my amazement, she and I made one of the same jokes in our writing, without any input from one another, and it’s an obscure bloody joke.

Velikovsky

There is a concern in the sciences of the idea of demarcation. The demarcation problem is the question of how do we tell the difference between science and non-science. This can represent a challenge when dealing with propositions that struggle with replicability or extremely complex systems – think like psychology versus physiology, or even whether there’s a scientific methodology that can be applicable to fields of art, literature, and religion.

The whole fundamental question of demarcation kind of lives in the space of where you can say science doesn’t apply here. The general idea for a time there was that you can’t use scientific methods to grapple with questions of religious belief, a position that was forwarded by Stephen Jay Gould with his framework of non overlapping magisteria. Notionally, science looks at facts while religion looks at values and therefore, these two things should not be seen as competing with one another, and should not be seen as threats to one another.

A problem immediately arises, then, when religion seeks to make fact claims; such is the problem with Young Earth Creationism or fundamentalist Christianity which uses fact claims to justify rules they demand people outside their faith. This can apply on big, important, political ideas like who gets to guide the country and by what rules, and therefore is of specific interest to me; another area it’s important is when you consider who does or doesn’t get to have a voice in a community of ideas.

Demarcation can be seen ultimately as a question of who gets to speak and where.

What if someone had an idea outside your field that made a whole bunch of complicated questions work…

… but nobody in that field would ever listen to their ideas?

Let’s talk about Immanuel Velikovsky.

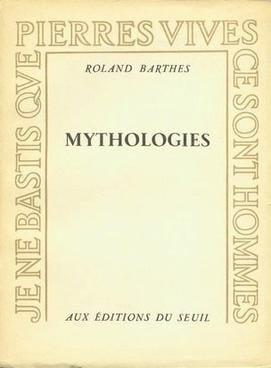

Continue Reading →The Most Important Book On semiotics In The 20th Century Starts With Wrestling

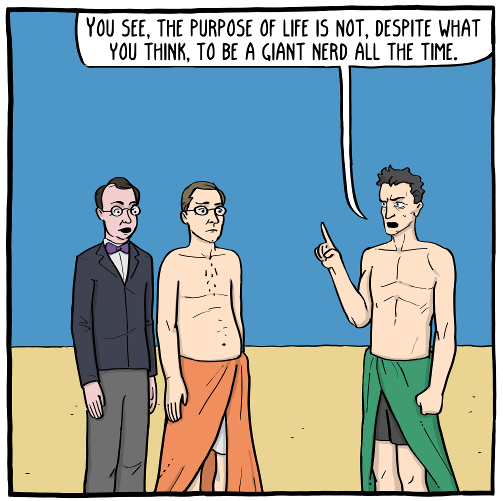

Hey, have you ever heard the phrase the death of the author? You might have, and if you don’t work at TechRaptr, you might even know what it means. That is, it’s the idea that the author does not hold any unique authority over how the story is interpreted. Wow, that was super easy to explain, why do people get weird about it, well, because people will get weird about it, and I am simplifying it for very comical effect. Well, it was an idea written by Roland Barthes, pronounced Bartz, like the protagonist of Final Fantasy V, I know, good joke, we all know the protagonist of that game is Faris.

Ten years before The Death of the Author, Barthes compiled and released Mythologies, a book in which he describes at length the way that meaning is made out of repeated use of symbols. This is done by a set of examinations of things about which we have myths — probably the most well-known is the example of how red wine is seen during winter as warming, and summer as cooling, despite being the same wine served in the same condition. The myth of the wine is not the wine’s material conditions, but what the wine is.

This book is dense and complex and, saying it as someone who is reading the English translation of the French with sixty-five years of distance between us that has been influenced by Barthes’ ideas, it’s honestly a real struggle to properly ‘handle’ the ideas in it. Like, even within his space, Barthes was a writer fond of fantastically dense text, where single sentences often used cross-referenced phrases or terms that needed entire essays of their own to unpack. The result is that even when I try to explain the text I can be easily distracted by the question ‘am I explaining Barthes’ idea, or using Barthes to explain my own idea?‘ which is impressive when dealing with works of art, but remarkably annoying when dealing with academic text.

Typically, Mythologies comes up in the conversation about what does and doesn’t count as a text. This is foundational to textual analysis at university, because you need to understand that [a text] is a self-defined parameter, where you get to say ‘the text is this thing I’m currently pointing to.’ But the examples he gives in the essays include, yes, red wine, but also soap commercials, and first of all, he opens with professional wrestling.

And you may think ‘hang on, not really professional wrestling, they must have meant something different in 1957’ and I must assure you: No. No he did not. In the essay he makes it very clear it is about pre-arranged wrestling with a narrative that cares about communicating what is happening in the ring in its own reality, not any kind of proper wrestling ‘sport.’ Indeed, he rejects the idea that it’s a sport (which I don’t quite agree with, but whatever), and that it is instead a spectacle.

It is not the realities of wrestling that matters.

What wrestling is is what matters.

I entertained the idea of doing a rewrite of this fantastically dense essay to update the examples to modern actors and agents, but it’s simply too hard. The essay is four pages long and just my notes on it are four times that. It’s so deliberately tight that to explaine Barthes runs the risk of explaining more about myself. What’s shocking is the ways in which he draws attention to some ideas that still are true about professoinal wrestling, including specifically the way wrestling is lit.

It used to be that wrestling would, just as a matter of practicality for the storytelling in the 50s, be extremely bright, and lit from the top down. This meant that anyone at any angle around the ring could see the action clearly, and nobody would be in anyone else’s shadow, and also, as a side effect, everyone gets kind of ‘brightened’ and ‘lit up.’ Contrast becomes moreso. These days, that same ‘light from all sides’ and deliberate construction of light is really important still: You don’t want lots of dancing lights around the stage (unless you do), so shadows are all obliterated with carefully balanced lights.

The result is a spectacle of a myth transpiring in the brightest of lights; in which you do not need to know the story to know the story; where you watch two people become, for a time, sun gods bathing in their own radiant light.

Wanna Know How To Hide Something?

Put it in a book.

It’s an old joke on university campuses that if you want to hide something, put it in a book. It’s a little bit despairing, as these memes go; the idea that we’re all filling books with words but we also know mathematically, most of them go unread. There’s an institutional value to distributing them and making sure they’re available everywhere for everyone, but we also know that one of the parts of contributing to the vast project of literally all human knowledge means that any given phrase you write is a drop in an ocean of your own work that is itself a drop in the ocean of your cohort and then that’s a drop in the ocean of even what, your generation.

The scale is dizzying.

There’s a related joke, where if you do a thesis, you should stick a $20 in it, and that way you’ll get to know if anyone looked inside it when you check in on it. I actually tried this – a $5 in my Honours Thesis, which I found at the library.

Anyway, turns out it’s not there at the library any more and I don’t know where they keep it. It’s just an Honours thesis, it’s not super important, I assume they’re kept in some part of the library with particular rules. Just funny to me to think about how even a stunt to make me check in on it regularly didn’t work. To be fair, a global pandemic interfered with my regular check-ins. I could put anything on this blog and if the context around it was wide enough, it could go unnoticed.

Makes me wonder what I DID put in this blog when I was less conscientious that’s just laying around like me confessing to some terrible deed or association. Or what someone could take out of context, like some phrase from a videogame review about how I like shooting at kids or something.

Could put any old bollocks here, really.

I’m pretty sure fish are too dumb to have feelings.

Explaining Sourcing

You ever noticed when someone says something in an article and the sentence ends with like (Mayonnaise, 2021)? That’s sourcing, and it’s a short-hand inline form made for a time of typesetters to say ‘check in the references list for the reference made at this time and this date.’ It’s a really remarkable system, not in how it works or what it does, but rather, in its application at scale.

Continue Reading →The Structural Failing of Dunkology

It’s easy to make people look stupid.

On the internet it’s incredibly easy to make someone look stupid. You can just take single phrases, put them out of context, and then you make the person who had the temerity to put words out there on the internet look like some kind of big stupid asshole. Any given quote can be put into contexts where it looks bad, a practice that’s very popular amongst Young Earth Creationists that we sometimes refer to as quote mining, or cherry picking. If you control the frame and context of words, you can make the work of any person with a meaningfully large corpus of language say almost anything you want them to say, and in the process, make them look foolish or useless or evil.

Ostensibly, there’s a solution to this; sourcing. If you provide a link to everything you’ve mentioned, people can look at things in their proper context. It helps to build a structure of all these arguments and positions around us, and it means anyone who wants to can look at your argument and the original source, and if they have sourced properly, a whole thread of sources going back to the root.

Continue Reading →Succubus, Incubus … ?

If you are prone to operating within the fantasy RP space, or MMORPG space, or really just almost any place where someone will use the word ‘cleric’ that isn’t actually and literally a seminary, you’re going to hear the word ‘succubus.’ It’s a classic monster, because it asks the horrifying question, What If Girls, and then follows up on it in a way that tells you a lot about the creator of the piece. It’s a term that, as I understand it, owes its origin to Malleus Maleficarum, which is also extremely sketchy on what a succubus actually is or does – most of the heavy lifting is done by the word itself, which implies its meaning, as succubus had a coherent Latin meaning from the first read.

The next term is Incubus – which you will usually see as a masculine alternative to the feminine succubus. The idea is that an incubus is a hot dude demon, who wants sex, and that matches with the hot girl demon, who wants sex, the succubus. This is the kind of thing you’ll see in monster manuals, where these terms for what is probably the same species or heritage nonetheless has gendered terminology, like, you know, livestock.

And of course, when this comes up, I will be a tiresome chore of a dude and I will bring up: That’s not what they mean.

Continue Reading →Caillois and the Transformers

Remember Friend Of The Blog (But Not A Good Friend Because He’s A Massive Weirdo And Has Creepy Views About Women And Colonialism), Roger Caillois?

The Beaver Drop

In the 1940s, Idaho needed to move some beavers.

Continue Reading →Jasper Maskelyne

I love stories about magicians.

Continue Reading →The Kids Don’t Meme

Or rather they don’t meme the way we do.

It’s been wild to me how much, recently, I’ve been dealing with kids. I didn’t intend to be a person who interacted with kids and largely, I’m actually very okay with letting kids go off and do their own kid stuff over there. I like to swear a lot and I don’t like having to deal with kids learning from me that the right way to use swears is all the fuckin’ time.

But my students are now at the point where I think I have to very sincerely consider that they are, to me, ‘kids,’ not because I want to infantalise them but because the age gap between us is equal to… well, their entire age in some cases. I taught a seventeen year old last year. That’s messed up.

Also, in order to better accommodate my young niblings’ internet behaviour, I’ve been doing my best to be a kind of internet sleuth. Their mother’s a teacher, and she hasn’t got the time to vet everything they want to watch in screen time, and what’s more they’re also going to be looking at new types of stuff all the time. Back in the day, we used to channel surf, now they can get a lot of concentrated stuff, and thanks to websites like ohhh say Youtube, there’s a potential firehose of Bad Stuff these kids can see.

From there I got in the habit of checking out some kids’ content on Youtube to make sure nobody was going to tell my niblings they needed to invest in the gold standard or something dumb like that. This is why I got into Hermitcraft, which is also why I’m on the /hermitcraft subreddit on reddit.

Now, I am not a snobby memer. I’m really not. But I am pretty seasoned at it. I study the form. In fact, I teach the form. Believe it or not.

Something that stuns me about it, though, is how often the formats of memes escape the attention of the people using them. There are numerous memes that are wielded not to convey the information of the meme form (an argument or a dismissal) but because the people in question genuinely want the meme to serve as a serious platform for their opinion. Petitions as memes, simple observations of two related things as memes, and so very often, ‘I am glad this thing happened,’ as a meme.

Students I teach, who are older and more sophisticated than this are still not particularly memey! They don’t necessarily get that the meme template informs the meme meaning, and that templates create meaning by being templates. There’s a lot of reaction-gifs-are-memes moments, where they have to be told that the image they’re using actually contextualises what they say.

It’s interesting because we made a big fuss linguistically about the millenial generation using memes as a Darmok and Jalad at Tanagra style language, but what’s really wild to me now is how a sublanguage is forming around the structure of the meme that is not attuned to its meaning. It’s a meta meme level, where memes are losing their associations and just becoming something simpler; there’s no need to layer ‘it’s a meme’ around something to explain it.

These are words I put on a page, but there is a picture of Spongebob, so I hope you will read them.

It’s wiiild.

Oh, and no pictures this time because I’m not about to put memes made by little kids or my students on blast.

Recognising Your Limits Of Knowing

This one’s going to feature some chatter from me as someone in a privileged position talking about people who lack that privilege. Just a heads up.

Recently I did a video article, where I mentioned that the idea that the main character of Fire Emblem 3 Houses could be read as autistic. At the time, I mentioned this was something I’d absorbed off other autistic friends and even mentioned one of them by name.

In the same week I recorded that audio, I introduced a early-transition trans girl friend to the idea of doortitting, where early on in transition, many trans girls misjudge the weight of doors and whack themselves in their extremely sensitive chests in a way that can be super painful and rough.

In neither case are these my experiences; all I’m doing is giving voice to things I’ve learned and heard from multiple other sources, and I try to make sure when I do these things I’m making it clear that I’m speaking of things I learned. There’s a gap between knowing and learning, after all.

Dara O’Briain in one of his comedy sets once related a story where an incensed Christian got mad at him for making jokes about Catholics, but that he didn’t have the courage to make jokes about Muslims. Dara’s response was that he wouldn’t tell jokes about Muslims because he didn’t know anything about them, and neither did his audience – there was literally no way to make a meaningful or funny joke from that position of complete ignorance, and admitting that ignorance was important and powerful, and it highlighted to me at the time the idea of how people are sure they know things when they don’t really. He then related a string of nonsense that may or may not be related to actual, obscure Muslim traditions and the point of the bit is I don’t know what he’s talking about.

There’s stuff I don’t talk about because I don’t know about it. I don’t talk to a lot of black women, for example. I can read black women’s work and I have indeed done so, learning amazing things about what Robin Boylorn calls blackgirlness, but that’s reading from an academic source. That’s not ‘my friend talks to me and I absorb culture through them.’ This means I’m typically resistant to commenting on black women’s issues except in the broadest way that hey, we treat black women real bad, that sucks, let’s stop doing that. When it comes to trans dudes, I talk to fewer of them than I do to trans women. Ace and autistic people are more common in my sphere, and that means I often think about the concerns they raise.

I think it’s important, and very healthy, to work out what it is you don’t know much about, even if not to fix that because you don’t want to approach friendships with an air of ‘You are my research assignment who will make me less ignorant of say, Southeast Asians,’ but just so you can be comfortable and confident admitting two crucial and important things:

I learned this from…

And

I don’t know.

These are invaluable tools for keeping your mind working well. Connect what you know to the people who did the work, and admit when your knowledge fails you.

The other thing is, and this is very important, even if in single direction relationships like where you’re reading a twitter feed of someone who doesn’t talk to you (like a big name activist or the like), is try to ensure you have a plurality of voices of types around you. When you listen to one black person, one gay person, when you’re not listening to marginalised voices but a marginalised individual, you’re making it harder for you to get interesting, meaningful, nuanced perspectives on these groups.

And when your media feed is one trans woman, you’re going to get that one trans woman’s take, and that, as we’re seeing, has led to some really rough stuff when people who listen to one trans women ignore all the other trans women who disagree.

The Cyberbard

Ever feel deeply embarrassed because you misplaced your notes and wound up committing an act of self importance in a way that nobody but you is likely to care about? Yeah, me neither. Anyway, in 1997, Janet Murray wrote a book called Hamlet on the Holodeck: The Future of Narrative In Cyberspace, and that book is a wild ride.

Now this isn’t going to be an Academic Blog Post (I mean I should save those for my Academic blog, smash cut to a bleached white skeleton gathering dust), but the book (which received an update in 2016) is a long form examination of the way that computers and communication technology was going to change our capacity for storytelling, with whole new theatres of technology opened up to the audience who could simultaneously engage with the work presented to them and create feedback loops that meant that the audience could shape the story that they best wanted.

This is kind of how things worked out, and kind of not, and you can look at the way that the internet has deformed the production of shows like Game of Thrones and Westworld for examples. Mixed in this book (which again, I’m only glancing through here) is an idea of the cyberbard. See, Murray was interested not just in how future stories in an online space were going to be created, but interested in how the tools for making those future stories would be created. She conceived of some truly dizzying stories being made at the level of, well, theatrical productions, and largely, the things she predicted did not happen.

Except the things she predicted, then arranged to have made, those are cool.

The notion of the cyberbard roots itself under the bard; the idea that there is a storyteller who can gauge reactions and give proper responses, fed by and feeding the audience in the loop of the communal storyteller. The bard did not just tell you a story they knew, they told you the story you were asking for, and the cyberbard is that same idea, expanded out into the realm of technological constructions.

There are a lot of things to cover in this book (it’s a good book, I liked it), but the idea of the cyberbard as an extension of technology and as an expression of the tools made to make those technologies is one of those ways that sometimes in academia we use small words to look through a mirror at an enormous conceptual space. The cyberbard is a storyteller conceived of and managed by a computer and it’s the way we build the tools that allow a non-cyberbard to make these stories and it’s the way that the rules of a cyberspace create the opportunities for these stories to be made. It’s dizzying!

But, in amongst all of this there are two specific examples I want to bring people’s attention to, because Murray was not writing about videogames, but about communication technology. She talked as much about things we’d identify now as blogs and web serials as she talked about the control interface of Janeway playing in the holodeck.

The first idea is that she suggests that any system of play in which you engage with a narrative, layered upon it, that changes the way you interface with the story, could be seen as a cyberbard. In videogames, this isn’t just the game itself, but rather, a system that lays atop the game, and encourages you to engage with the story in a way you might not otherwise, for a piece of specific feedback.

In this case, the Let’s Play’s need for content is a cyberbard; the twitch streamer engaging their audience is a cyberbard; and so to is the achievement system, directing the player to do things they wouldn’t do simply to be marked as having done it.

The second, and perhaps larger idea is the notion of a transcendental, collective artwork, an example of theatre, where people could gather and discuss and express their wants for the story going forwards, and the author could, in the mean time of the making of the narrative, enact and express that multimedia story. The book seems to think this would be being made like a television series, a soap opera with shooting and actors (even virtualised ones). What she didn’t anticipate was a massively democratised production apparatus, which meant that these dramas were being made not by people with access to enormous budgets, but people who could harness the right kind of focused attention and engagement.

In 1997, I feel, Janet Murray predicted Homestuck, though she never would have said so.

I’ve had this in the drafts folders for two years, get out of here, you curse’d blog post.

Decemberween: Surviving my RPR!

I say that like it’s something I did but I think it’s really just because I’m still numb that I did it. I think back on that hour or two of waiting and talking and asking and waiting and waiting and waiting and I feel sick to my stomach thinking about the mistakes I made. It was weird to enter with so much confidence I downplayed myself in the name of not looking like an arrogant dickhole, and in the process it all twisted around on itself.

My PhD scares the hell out of me, and every time I stand in front of an actual academic and explain it, I feel my grasp on my confidence slipping away. It’s scary!

But this year, I did my RPR, my first major presentation on the Phd to someone who doesn’t know the field and doesn’t know me. It didn’t go amazingly, I missed some specific details and – and –

You know what.

The thing is, the real reason I want to write this.

My supervisor and my co-supervisor went into a small room with two of their peers and went in to bat for me. They didn’t defend the indefensible, they provided context that was meaningful.

I’m not saying my work is bad and my supervisors made it look palatable. I’m saying my work is good, but I’m not yet good at making that clear, and my supervisors did heroic work in standing up for me. It’s a huge deal to me, the way I can feel cared for and respected by these people.

It means a lot to me and I’m very grateful for it.

Academic Success

I usually share this when I’ve released my students’ marks at the end of each semester, captioned with okay here’s how the marks break down.

It’s a cheap gag but let me have it.

Anyway, I was thinking about this as it pertains around about now to getting your marks back. Now I am one of those people in the long slow treadmill of the PhD candidature, so it’s less of a thing for me but I am sibling to teachers and that means I’m always thinking about the marking process, to some extent. About the ways we grade and what we grade.

I have come to have the position for the most part that marks aren’t super important – the only people I’ve dealt with who cared about how well I did at university for my subjects are the uni itself (in determining my use for Honours and the PhD).

There’s an old cynical joke ‘Cs get degrees,’ which is meant to refer to C grades. Except we use C to mean Credit, so we move on to ‘Ps get degrees,’ which refers to passes. More cynically we say ‘Fees get degrees,’ where the fact is, if you pay to the uni your fees, odds are good you’ll pass, no matter the quality of your work if you hand in enough stuff to count as having done the degree.

I apparently did pretty good at university (hence the PhD thingy), but I also seem to project ‘person who has his shit together,’ in a way that I think is very unfair. My students are only dealing with me as someone who has done the course they’re doing and has authority and the means to grade them. And what’s more, me saying ‘I bombed out at the high school certificate’ doesn’t necessarily land.

What happened to me is too unique, I feel, to really ‘matter’ to most. I was raised in a cult, schooled in a small wooden box, broken and abused, then did badly in an exam questions that were designed for people who’d had twelve years to prepare. To give you an idea of how badly I did at it, my grandmother phoned me up – something she only did for birthdays – and spent a few hours degrading me for not applying myself and failing at the test. This is not relatable. This is weird.

That it took me ten more years to get into uni because I thought I was too stupid to do well at it, and now I’m here I love it, is a byproduct of the complete lack of support.

Here’s my advice if you’re going into uni: You will probably not have to worry much about marks. Marks happen when you’re engaged. Passes are fine. Doing the minimum is fine. What you have is a period of a few years to work on creating and exploring projects, and if you can, make something that you can make into classwork. Convince teachers to let you work on your own stuff as it relates to their stuff. Then you have that as you walk out the door.

And also, my grandma was a dick and you shouldn’t listen to the dicks around you when they want to talk about what you should be doing, in uni or in life.

The Attack of the Dead Men

During World War 1, German Command received a message that their offensive had failed and been routed by a charge of zombies.

Content Warning: World War I, descriptions of gas weapons

The Author Is Suspended

One thing that you deal with when you read a lot of academic books and texts is you get an impression of the writer. It’s not just that you read the book, it’s that you read the book over and over again, and you read certain passages over and over and when you do that, you need to be able to contextualise those passages in the greater work, and that means you’re encouraged to form a framework of the opinions and beliefs of the person you’re reading about.

Sometimes this is very useful; it’s illuminating to remember that Heidegger was a Nazi (and people can um-and-ah about that point) or that Caillois a misogynist (amongst other things). These people write about things where those perspectives are implied but not stated, and being able to put their behaviour in their own contexts is not a bad thing.

Still, there’s a risk you run when you do this kind of close reading, especially when dealing with academics who are still alive.

One idea I use a lot in my discussion of games and plays is that the play of a game is paratextual; that you play the game to experience its text, and that represents a boundary between ‘definitely the text’ and ‘definitely not the text.’ Play is not something the author put there, but they definitely put something there that the play happens with. But the idea of paratext was not made for games – it was developed by Gerard Geanette to talk about books, specifically books as objects, with ideas like dust jackets. The idea that play is paratextual seems to be from me, and it’s not widespread. That means I’m taking an idea someone else had and using it to explain something else.

That’s how academic reading and studying works, but here’s the problem: I have no idea if Gerard Geanette would agree with me. I don’t know if he thinks this is a good application of his idea or, even if he didn’t like it, that that matters. I’ve never gotten the impression Geanette particularly likes board and videogames. I’ve always had the impression that he loved books, a bibliophile who found reason to discourse about the weight of paper and its influence on text.

Moreso than that, in Alien Phenomenology, Ian Bogost relates an incident where he, generating a little web tool that created random banners, was reprimanded (sort of?) for putting a label of ‘WHAT IT’S LIKE TO BE A THING’ over a picture of some women. It wasn’t done specifically – it wasn’t something crafted to his ideological position, it was just something a bit of code he made did.

I have read this anecdote a dozen times or more as I grapple with explaining and justifying the philosophical conception of things existing, and seeing it over and over makes it easier to remember. Easier to put a sense to. Easier to imagine having a tone of irritation.

Thing is, I think odds are good that Bogost is not only over the mild discouragement he got for this web applet doohickey, but that all the irritation in his tone that I read in his piece is entirely in my head. This passage doesn’t have emphasis or sarcasm notes or colour coding. It’s very stark text in the same voice as the rest of the book. Yet I keep coming back to this passage, to this moment of an author’s mindset, and find something there, something I don’t think I found the first time I read it. And the author, frozen in time, has nothing to tell me but what they already told me. Hanging, suspended, for my interpretation of invisible ink.

Be vigilant about the assumptions you find in work, but also be vigilant about the assumptions you build to make telling the story to yourself easier.

Goldshire Inn Ethnography

Before there was photography, there was heliography. It was from around the 1820s, and to make a picture with heliography you needed to get a big funnel-shaped distorted mirror to capture sunlight and direct it through a glass lens and onto a plate of chemicals and it created an image. Things had to hold very still while the sunlight ‘etched’ onto the chemicals, and it was pretty quickly outmoded by photography.

The heliograph was used in its narrow window of time in the – haha – sun, to take pictures of naked ladies, who came in and held poses long enough to get shadowy silhouettes made.

In Game Research Methods, Lankoski and Bjork explain a bunch of different methods for studying games academically. It addresses techniques that are unique to games, ways that games fit in with existing research tools, and challenges that games have that people unfamiliar with them won’t necessarily consider. This is where I first got the idea of Stimulated Recall, where recording yourself playing a game, then watching that playback is a chance to talk about and experience your mental state and give a more accurate accounting of the play experience.

This book also includes a really interesting chapter about understanding the ramifications of ethical disclosure in digital spaces as it relates to subjects (people) and their ability to share information. That’s a big sentence but it’s basically a finding from a researcher who was studying people ERPing in WoW.

Now I’m not going to infantalise you and pretend you have no idea what those acronyms are. For the sake of completion, though, ‘WoW’ refers to World of Warcraft, and ERP refers to ‘Erotic Roleplay.’ It’s got a lot of possible terms but the basic idea is using text roleplay in a game’s shared space to roleplay out sex.

Now, some people react to this discovery with incredulity, which I find kinda tiresome, but yeah, if you have literally never heard of this: People do this. In fact, people doing this is as old as the internet itself. In fact, back in the day, before the internet, people used to write dirty letters to one another, to make up a sexy narrative. Like, written with hand. There even used to be a whole range of clever acronyms for those dirty letters, a hidden language that was designed to convey information to the insiders and keep the communication fast and fluid.

A lot of those letters you see people reading in World War 1 re-enactment dramas, a tearful moment as the music swells and you, the audience, reflect on this humanising moment as this soldier is connected to their home country and given a reason to feel just for this moment not here in this filthy trench?

Those letters were really dirty.

Anyway the chapter is interesting and includes a lot of self-examination from the researcher, who realised that their work was not just about examining the interactions of objects in a space, it was the behaviour of people, and reading logs of people boning meant getting insights not just into the practice academically, but also the way people feel about themselves, and one another. About the meaning of our virtual bodies, the bodies we use to express ourselves, and it’s all very good reading and it’s very interesting about designing your data capture so it takes into account the ethical needs of intimate places that players create. It’s really interesting.

It’s also four years old, and built on existing research into ERP. Which is why I know those things about those filthy letters, and about the heliography of naked ladies. People make stories with one another, and people use technology, and one of the most common things people use that technology for, and make those stories about, is, well, sex. Sometimes weird sex, sometimes chaste sex, sometimes circling around not wanting to call it sex.

I guess I bring this up because I still see people using ‘people ERP on the internet’ as a punchline. Sometimes a website like Polygon or Waypoint will talk about it and in a very hamfisted way I get to watch as other people slap at the topic with a lack of nuance that speaks of embarassment.

People do this. It’s not weird. Try and have some chill about other people’s fun.

Unserious Queeriness

My first draft for everything this month has been a series of articles that are mostly me yelling angrily about various fan theories about how queer series aren’t queer, or how easily you could queer a series and improve it (Blacklist), but one thing I’ve been avoiding doing too much is talking about work that you might think of as serious queer media.

I have a couple of reasons for this. One is that I tend to find this stuff really super alienating. I’ve been looking for options of Queer Media to cover that I think I can cover in a way that’s useful or meaningful. It has involved interrogating what I even talk about, or why.

Let’s really quickly mark out three types of Queer Media that I don’t want to talk about here: There’s the two spaces of Horny Queer Media which I hope is just pretty obvious, and what I’m going to shorthand as Painful Queer Media, which is where you get your tragic personal memoirs and personal accountings of abuse or transphobia or lesbiphobia or so on, or how hard it was to get your first gay experience, or that sort of thing. Singular, personal vignettes.

The third type, which I’ve talked about already, is Subtextual Queer Media, where the queerness isn’t there so much as it’s easy to see queerness if you know about it. You know, stuff where it’s Queer, and the Fanbase are very sure it’s Queer, but if you can watch it as someone who doesn’t know what queerness is, or who believes that same-sex people can just be friends, then it doesn’t make you ask questions.

Now, I feel ill-suited to talk about Horny media. I had an explanation, but… nah.

Just nah.

And when it comes to the Painful Queer media, I just don’t feel like I’m qualified or that I can offer a meaningful insight. What’s more, showcasing this kind of work feels like the wrong fit for me. Not that it’s not valuable or meaningful, or that I think you shouldn’t make it if it’s the kind of art you want to make.

The idea that Queer media is confined to this space where the art has to be tragic, has to be painful, or it has to be completely facile reminds me of Hannah Gadsby, in Nanette, talking about how for the people who aren’t beneficiaries of the privilege system of our world, to stand on a stage and lay bare your soul is not an act of humility, it is an act of humiliation. I don’t think that I have a meaningful lens to offer on that.

I want to write about adventure. I want to write about heroics. I don’t want to try and make some way to connect my damaged soul to the writings of say, an enby making a game about the challenges of American medical health care. I’m damaged in different ways, so I can’t really offer my meaningful lense to the matter, and I don’t want to hold up these traumatic experiences of other people as if I’m somehow good for showing you this thing you totally would never have checked out if I hadn’t shown it to you.

That’s not what I want to write about either! I don’t see the value. My damage and my situation aren’t, I feel, taken seriously in queer spaces, so it’s not like me saying ‘here’s how this intersects with my pain’ is meaningful to anyone. Tragic manpain, I’m sure. And if I can’t meaningfully contribute to the conversation, I don’t want to be seen as performatively looking at things that don’t speak to me. It was bad enough to deal with a month of romance games that made me feel gross, after all.

Nah, what I want to talk about is fighting and reasons. Characters and motivations, people who do stuff and why they do that stuff. Slow boiling coffeeshop AUs are for other people. Instead, I want to show you queer adventures and stories about fighting baddies and punching dragons and slaying or being cool monsters, but like actually being a cool monster and not a monster being a metaphor for atypical body types and therefore you just want to play videogames and sleep in. That means that I lose some space for complexity, which I guess I’m okay with, because what I lose is stuff I wouldn’t do a good or meaningful job dealing with. Let’s instead spend our time finding queer media that isn’t About Queerness but is instead about Doing Things where Queerness is an assumed standard. I can do fun and goofy and non-intense.

In the words of Griffin McElroy, This is a ding-dong podcast.

Wittgenstein’s Outsized Example

Today – so months ago – I spent some time reading Wittgenstein. If you’re not familiar with Wittgenstein, he’s one of those philosophers you’ll find if you do a sort of ‘greatest hits’ compilation of the 20th century. Definitely important and all that, contributing to the logic of mathematics and language.

Anyway, the thing is, Wittgenstein has this really weird relationship to game studies in that it seems traditional for everyone to write in their earlier stages a discussion of what a game is. This discussion inevitably brings up that Wittgenstein, in his book Philosophical Investigations, used the difficulty of describing ‘games’ as an example of the ambiguity of language.

And then, for sixty years since, academic writers and game scholars have taken issue with this half-page of text, the single example he offered as a stepping stone on to other topics. In fact, in some cases, they get downright personal about it!

Now here’s the thing, the thing that means me here, in the year of our Luigi is so frustrated by this: Wittgenstein didn’t really care much about games.

It was an example! It was just a language example of a grouping of things that we can all intuitively tell are connected and reasonably share traits, but don’t necessarily have a checklist of clearly and easily defined commonalities! And while sure, you can take issue with that framing, and I mean, Bernard Suits’ definition of games is the one I use but it’s still really stunning that it comes from arguing with Wittgenstein as if Witty was being Very Firm about Games, and not about language!

Imagine being so good at examples, being so renownedly smart, that years later people were building books around addressing an example of yours to tell you you were Actually Wrong. And then other people would come along after them, to disagree with them and you to try and make a point that you were definitely wrong but the other person saying you were wrong was also wrong.

And this is on a topic you kinda don’t care about!

Ethically Expert

I am at this point in my life, at least accomplished enough in reading some books and mentioning those books by name in the middle of other sentences, something that you could consider, or at least be fooled into thinking, is an expert. I have done things that other people have not yet done and I’ve done a LOT of them – it’s not just that I’ve made and sold a game, it’s that I’ve made and sold dozens of games, for a few years now. It’s not that I’ve got a degree in business communications and media, it’s that I’ve got a degree, and honours, and am working on the next level of academic study.

What’s more, the kind of thing I’m studied in isn’t something that most people really know that much about, or even know that there’s much to know. Oh, videogame fans may think that the entire field of games studies or media theory is pretty meaningless, and that beating Dark Souls means they’re more capable of knowing about how humans deal with or make games than anyone who’s actually studied them, but broadly speaking if I meet a stranger and tell them I’m working on a PhD in making tabletop games, they’re largely inclined to nod, smile, be polite, and say ‘Oh, that’s interesting,’ and if they’ve got the time, ask me some questions, and then all that expertise and my own native curiosity kick in and we talk about something that matters to them and how it relates to my field of study.

It is fun and I like doing it, because I wouldn’t be in this subject matter if I didn’t love it, but it’s also something I’m aware generally relies on them trusting that I know what I’m talking about. That trust is pretty freely available, especially amongst people who don’t think they’re experts.

Now, recently, a piece was published in the Atlantic that wanted to talk about rhetoric and argument as an art that was created in Ancient Greece and then sat completely still, unchanged and waiting for someone in the enlightened 21st century to point it out, and can you all please stop making fun of me on the internet. As a direct result of this, people who did know about rhetoric and academic study of argumentation spent the afternoon quietly exploding about watching their discipline finally get some mainstream journalistic attention, only for it to be touted by the kind of babby talk doofusry that showed the author of the piece was only seen as capable of commenting on it as what we might call a wikipedia-level surface-reading scholar.

I’m not going to link the piece, because the dude in question is a transphobe and I think heavily invested in the idea that other people on the internet should definitely show him more respect just for his awful, horrible, miesrable opinions that get kids killed, but he does put me in mind of something that worries at my mind a lot, something applicable for my life.

By the way, one of the applicable things is ‘Don’t be a transphobic asshole.’

The other thing is that to most people, I am an expert, as far as they know, and I have things in my life and history and my demeanour and my tone and – let’s not kid ourselves, my whiteness – that make me seemingly more qualified than any random. And with that trust can come a lot of dangerous implication. I mean, it’s not impossible that I could find someone with money, who was a total asshole, but who wanted to be told their total assholery was correct, and then spend my time telling them what they wanted to hear, rhetorically turning and tuning whatever nonsense they wanted into things that sounded legitimate. I don’t want my positions on things to be taken up as forms of harrassment or attack.

This is a concern that really eats at me.

And so I continue; the need to cautiously temper myself, the need to make what I say reasonably easy to understand, and to root my explanations in either my own sincere feelings, or in scholarship and other sources that I can point to. That’s one of the reasons why I mention the names of these scholars: It’s not to show off ‘look how many books I read.’ It’s to make clear the fact that whatever it is I know, it is rooted in a long and wide tradition of other people, that I am standing on the summits of hills made of giants, and all I really am trying to do is describe, to you, the view.

British Currency

Years ago, as one of my research projects, and to show off a bit, I talked about Australian money, because Australian money, unlike most other cultures’ money, is good, or at least, better than yours, or, most importantly, better than America’s, which is really bad. At the time I had the fanciful idea of maybe examining a bunch of different culture’s money, but mostly they all repeat the same basic-ass mistakes as the American money, which I think is possibly because American money is the template a lot of other countries use (why).

Still, there are at least two other countries whose money I think is worth talking about, and we’re doing one of them today: the British currency. Talking about Australian money took a long time, weeks, with stories about every figure involved. Talking about American money took a short dismissal, because all American money is bad.

British money needs a little bit more space, but less than it should.

Let’s go.