There is a concern in the sciences of the idea of demarcation. The demarcation problem is the question of how do we tell the difference between science and non-science. This can represent a challenge when dealing with propositions that struggle with replicability or extremely complex systems – think like psychology versus physiology, or even whether there’s a scientific methodology that can be applicable to fields of art, literature, and religion.

The whole fundamental question of demarcation kind of lives in the space of where you can say science doesn’t apply here. The general idea for a time there was that you can’t use scientific methods to grapple with questions of religious belief, a position that was forwarded by Stephen Jay Gould with his framework of non overlapping magisteria. Notionally, science looks at facts while religion looks at values and therefore, these two things should not be seen as competing with one another, and should not be seen as threats to one another.

A problem immediately arises, then, when religion seeks to make fact claims; such is the problem with Young Earth Creationism or fundamentalist Christianity which uses fact claims to justify rules they demand people outside their faith. This can apply on big, important, political ideas like who gets to guide the country and by what rules, and therefore is of specific interest to me; another area it’s important is when you consider who does or doesn’t get to have a voice in a community of ideas.

Demarcation can be seen ultimately as a question of who gets to speak and where.

What if someone had an idea outside your field that made a whole bunch of complicated questions work…

… but nobody in that field would ever listen to their ideas?

Let’s talk about Immanuel Velikovsky.

Some boring biographical details and I promise this isn’t like last year where I sprung on you the dude had spent his childhood making Himmler look like a dipshit. Immanuel Velikovsky was a Jewish Russian-American … you know what let’s focus on writer for now, because his other achievements kinda have to live in the shadow of his writing.

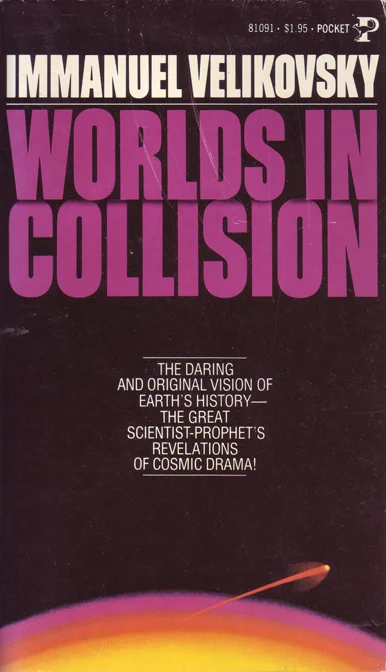

What Velikovsky wrote was a book called Worlds in Collision, published in 1950, and it was not published to a scientific audience but rather to a general audience. See, this book wanted to approach a big set of problems and present an idea to explain them all at once. If there were a set of problems and incongruity across a wide variety of sources, the book reasons, then there may be many small confusions or errors throughout these sources that explain the incongruity, but there may be a single explanation for all of them that lines up an answer to these confusions.

Velikovksy proposed in his book a bunch of events in a timeline, but which more or less cook down to the idea that a number of mythological narratives across numerous cultures throughout human history record real observed events that represent the movement of planets in our solar system that have been radically different within recorded human history. The preponderance of global flood myths across the world, he proposed, means there was some global flood, and then over time, cultural amnesia kicked in and we regard those events as fanciful, rather than recording of real history.

Thing is, a lot of the celestial mechanics don’t line up; records in ancient China and Egypt and the Mesoamerican data we have (such as it is) suggest that these events don’t line up properly with all the other events in this paradigm, which meant their dates needed to be adjusted. Adjusting their dates mean their celestial observations had to be wrong, which, when aligned, could create the impossible, inescapable conclusion that once, within human history, Earth didn’t orbit the Sun, and was instead a moon of Saturn. When Saturn had a nova event, it ejected earth across the world, creating a period of tumult, until it settled into its proper location, a period of chaos so immense almost all the records of it are lost.

almost.

Instead we have myths, stories of a ‘pre-historic’ world, ideas of a time when everything was fundamentally different and then we had the world changed to the way it is now. But the solar system wasn’t done playing billiards yet, because Jupiter ejected a chunk of its mass, throwing into the solar system a new player that had to get its atmosphere from somewhere – stripping off some of our atmosphere as it rocketed past until it settled into its position we now see, in the form of the planet Venus. Its atmosphere? A hellish boiling earth-like expanse of hydrocarbons.

This, Velikovsky argued, explained a lot; the period of comets and signs of Roman history; eras of plagues and wars, the collapse of civilisations that seemed unassailable beforehand, and of course, events considered mythical in the Old Testament, like the Egyptian plagues’ period of darkness, or the way the sun stood still for three days in the conquest of Israel. This revolutionary idea attacked orthodox views at their very root: it required the re-structuring of entire historical frameworks, where celestial calendars were seen as a reliable way to represent different periods of history and create a concurrent timeline of reasonable historical events across diverse cultures, and it drove things normally considered fanciful and fictional into prominence as now, considered, real history.

It was a single question, whose answer transformed the entire vision of history and which presented a new, fractal, spanning vision of our own place in the cosmos that was blinding in its dizzying potential. The first man did not see these same stars, was not born under the same sun, and did so on the far side of an era of dreadful darks.

Anyway, it’s all so much pigsmoke.

If you’ve never heard of this guy and this is your first acquaintance with his ideas, you might have perhaps gleaned a certain Chariots of The Godsness from them, for authors in the 20th century just pumping out popular ‘science’ books that sold well, but also bypassed actual scientific review for some reason. I’m not being unfair here about his positions, by the way; Velikovsky’s work generally covers what I outlined and lines up with mostly the events he described, even if it’s a bit hard to summarise all of them in one spot. They changed a little over time, and he sometimes had ideas he wrote about at length but never published about because of the pushback other, related ideas got.

The idea is novel, and chances are if you heard about it at some point about a thing that happened in Deep Time, you might go ‘oh, wow, really?’ I know when I first learned that Earth’s moon is a chunk of Earth that got knocked off us when another planet smacked into us some half-billion-years or more before the first cellular life happened, and that moon may have been instrumental in stabilising the earth, I thought ‘surely that’s bullshit’ and I had to learn a lot about how we know it’s true. It’s possible from that same position, the idea that Earth once orbited differently, and a change in that orbit resulted in our current now could seem like it was a meaningful idea, just like how you might be easily convinced that Venus came from Jupiter, because – well, it had to come from somewhere, right?

One of the reasons Velikovsky published a popular science book and not papers was his lack of qualifications in any of the fields he touched. He was a psychoanalyst first and foremost, but his radical idea explained to his satisfaction, the way that he wanted mythologies to be real, and all he had to do on the way was project a series of events so massive it defies analogy. It’s hard to convey to you just how off-scale Velikovsky’s ideas are; Venus took 4.5 billion years to settle into its current space, and he figured it could get all of that done in about three thousand years.

Look, let’s treat this like money; the budget says to get Venus where it is, with its current attributes and movement, would cost 15,000 dollars. Velikovsky budgeted one cent for it.

There’s so many questions in Velikovsky’s ideas, too. Why did Jupiter disgorge an entire ass planet? Why is it necessary Venus’ atmosphere brush ours (and uh, that’s really too close, just saying)? How can this period of planetary wandering be proven, considering how far back Saturn was? Where’d all the heat go? What happened to the moon in all this? The way he answered them was some mix of uh, ‘cosmic forces’ and ‘electromagnetism.’ If you’re not familiar, ‘electromagnetism’ is the go-to explainer for pretty much every peddler of woo who isn’t doing it through quantum theory. Particularly, flat earthers love it.

If, occasionally, historical evidence does not square with formulated laws, it should be remembered that a law is but a deduction from experience and experiment, and therefore laws must conform with historical facts, not facts with laws.

Immanuel Velikovsky

This gets us back to our idea of demarcation. How do we tell the non-science from the science, and what do we do with the science claims of the non-science? You can work out if Velikovsky’s theories are true, after all, it’s all chartable; you can measure where Venus is and how it goes and chart it back through orbital mathematics and get yourself a reasonable set of information about why Venus is where it is and how stable it’s been and for how long. It’s complex math, famously some of the hardest math you can do, but you can do the math and all you need is the math to see that Venus probably didn’t eject from Jupiter a mere few thousand years ago.

There’s another question at the other end of it, too: What the hell does this get you? What meaningfully changes in the world if this list of impossible propositions are somehow true, despite evidence to the contrary? Well, the reason Velikovsky pursued it, and what he was interested in, was the idea of presenting stories from the Old Testament as being factually true.

And that was important.

It was important, because if the Old Testament wasn’t factually true, then the history of Israel he believed, where an actual literal God bequeathed a country to them after slavery in Egypt and an Exodus, and which they earned through multiple genocides, was based on just a story. It might not be true. And it might not justify, you know.

Another genocide.

It’s a bummer, because outsider and new ideas are great. In Academia, the fact that I’m just younger than my peers means I get a lot of people asking me what I think of things and curiosity about how things look to me because I’m not entrenched in the same sources. The readings and study I bring to bear is different, and that can create interesting ideas. We are constantly looking to people who can shed new light on ideas, and then there’s the confrontational exercise of peer review, where you put something in the public eye and watch as people you don’t know are given every bit of motivation to find what you said wrong and address it. Publically.

“My point, once again, is not that those ancient people told literal stories and we are now smart enough to take them symbolically, but that they told them symbolically and we are now dumb enough to take them literally.”

John Dominic Crossan

Anyway, I know about Velikovsky because my dad once spent a long car ride explaining him to me because he thought he had some interesting ideas that verified the Bible.

Remember, every church has a conspiracy theory.

1 Trackback