Sprint: Four Characters Describe Brother Fratatelli

Know One Stone? No? Well, this might be hard to follow. I’m thinking about how badly the characters in that book are explained visually, how I don’t take opportunities to really go indepth with how characters look. Here then is a test text sample of how each of the major characters in One Stone would describe one of their own, Brother Fratarelli. He’s a priest, he’s nice, and he’s fat.

I am particularly keenly conscious of this last point because rereading the book I kind hammer on the fact he’s fat in some really pointless ways. Rafe in particular refers to his fatness in internal dialogue a lot, and I need to bore into why Rafe would do that.

Anyway, the simple idea I had at first was that of the four characters:

- Rafe sees class signifiers

- Aderyn sees weaknesses and objectively verifiable surrounding material

- Kivis sees emotional boundaries

- Fratarelli himself sees anxieties and fears

Here then!

Continue Reading →The Magic of Goo

You know that book I wrote (that I’m willing to admit)? One Stone? The story set in an alt-history British Empire at some mangled point in history where they have guns and trench warfare in the middle east, but also farmers unions are recruiting to mass-harvest food and oh yeah, there are dinosaurs. It’s an ahistorical setting that’s about how stories about fantasy kingdoms that are clearly England feel to me, as an author raised on those stories from the wing of the empire.

I mentioned, offhandedly, to someone recently that the magic system of One Stone is – and they interrupted, asking hang on, what magic system?

Continue Reading →Paperclippers

If you wanted to right now you could tune into Youtube or a bunch of podcasts and find any number of people, super soldier programs, space pilots, remote viewers and scientists who will tell you what life is like, in space, working for the space force, you know, the secret space force, and time spent on Mars, dealing with the natives and their relationships to earth life things like – well, you’d call them cryptids, like how they relate to benevolent cuttlefish AI in the political positions of the Sqatch. You know, the kind of thing.

And… they’re fantastic and exciting and they’re sometimes confusing and they’re usually incoherent and they almost always rely on some stuff that sounds like it doesn’t make sense, and the reason it doesn’t make sense is because you’re hearing the most exceptional stories of the most exceptional people filtered through the work of a lot of the rest of us.

And I mean a lot of us.

Dabbling in Audiobooks

I’ve been listening to some audiobooks lately. Nothing major – one a book I’ve already read and one a book I never had. And immediately, I have to bring up something that I’ve been stewing on: do I say I read the book?

Continue Reading →Like A Dog

I have learned

In the small time I have had

With this gangly

Dangling

Enthusiastic

Greedy

Awkward

Flailing

Noisy

Four-legged

Creature I call a name

That a dog exists at all times in a state

Best summarised as ‘Optimistic.’

He sees every time I change my shoes as a chance

(For a walk, you see)

And every time I prepare some food as a chance

(For a treat, you see)

And every time he is told to do a thing

And he does it quickly

That is a chance

(For a reward, you see).

He rarely gets these things.

It is known to me that not every dog is like this

But it seems so simple

And so effortless

I fear that it may be that every dog is like this

And those dogs I see

That do not look up when you move

That do not check for treats

That do wobble with enthusiasm for what good may happen

Have been trained to not hope

I fear sometimes what I learned

That a dog was lucky enough not to

Mental Diet

It’s like, 1.30 in the morning, a November night, and I didn’t write anything today, until now. I worked on some projects – a little bit in a few places – but the main thing that happened today was that around 4 pm, I told my friends ‘I think I’ll lie down, but I have my phone,’ as if I would chat to them while in bed, then woke up four hours later to find everyone asleep.

This is because in the morning, I woke up bolt awake, holding on to Fox and the dog because I’d had a nightmare about the Rapture. These are not uncommon things for me, like I’m not surprised by them, but they do pretty badly exhaust me. It meant that I just didn’t get much sleep – I was asleep, but it wasn’t restful sleep – and when I was tired, I didn’t want to go back to sleep, because I didn’t want to return to the nightmares. The fear that I would fall back into that place, as if the dream is a place I was going to go, not a dumb trick my brain plays on me for thirty years.

But that meant I was exhausted today. I shambled around a little, I watched some Youtube videos, I planned for dinner – I did some laundry! Hey, go me, that’s a chore I easily would forget. But then I went to bid at four twenty nap time, and whumph did not wake up until 8.30.

Then I watched a movie with Fox, and we recorded a podcast about it, and we went to bed. She watched AmberCyprian and Argick play a game about balls on a string – Argick’s channel is really top tier balls content – and I kid you not I spent about a half hour watching minute and two minute clips of things like capybaras jumping into water.

It’s been a bit of a rough day.

Continue Reading →The Century Ship

Your parents built this life for you.

Their parents built the life of building this life for your parents.

Their parents, and their parents, and their parents.

Over and over.

It had a name at launch, but it’s just pointless trivia now. Here, in this sector of space, they just call it Century. Derived from what it was called at first, The Century Ship.

It was an enormous project. Not the only one of its type, though; just one of the first efforts from earth to make an interplanetary colony, launched at a targeted region of space with a monstrous ship; practically a city, really. It was a long project. It wouldn’t arrive in ten years, not twenty, not thirty – it was sent off with almost nothing in terms of propulsion or control because if they didn’t get it right at the start, there wouldn’t be any way to solve it afterwards. No, the important thing was making sure the colonists could escape orbit safely, life safely for long enough to have some real actual whole babies, arrive safely, and thne set up the new colony. It was a project more like building a city, a population centre that could sustain itself for almost a hundred years. That meant it didn’t just have to be mathematically correct – it had to be interesting.

It had to have culture and fun and pleasure.

It had to be nice.

Now it wasn’t your parents’ idea, per se, or their parents, or their parents, but the people at the base, setting up the launch, starting the plan, they wanted to make sure that the culture that they got at the end was the culture they wanted. They wanted colonists who would know the history they wanted to tell and feel the way they wanted them to about the place they got. The longest of games, infrastructure for enormous investments, trading on futures and a crafted culture.

The libraries were chosen, the games were created, the sociologists were consulted, the workloads were set up, the labour was maximised and the leisure was optimised, and everything was set in place so the Century Ship could be a living city that, in generations of time, would arrive in a new home and start the new future. It was one part a labour ecology, one part storage of supplies needed for the landing, and the rest…?

The rest was a mall.

A little fake economy moving fake chits of fake currency around so people could make interesting choices about how to spend their time and the feelings of their rewards of their efforts. Contained and controlled. Sure, give ’em a kinkos. Let ’em have that.

Then there was a problem.

The generation that was meant to stop the ship and land it and start the colony…

Found people living on the planet.

It wasn’t unoccupied. It was not going to be an act of landing on unoccupied lands and starting a new history. To the surprise of the computers, this created the first and most major ethical dilemma in the ship’s history.

What do you think happened?

The Synthetic Mystic

The sector of space has the remnants of an old world. An old war. When the corps arrived and started colonising the space, they did their best to scrub those signs, and honestly, they did a pretty good job. Lots of the hard worlds were easily scrubbed, as nature can do a lot to clean up ruins with enough time. Fence out some worlds so nobody goes looking, brand some things right, build your own stuff the right way, and make the history hard to find, and you’ll find people assuming a satellite that’s old and beaten looks a decade old, not the centuries it was when they got here. Fact was, the light speed tech that let the corps get here here, and the technology that let them establish a network gates and planetary systems, wasn’t something they built, not themselves – they just deciphered the signal from aeons past that called for them across the stars.

The signal helped them push the boundaries of technology and the barriers of space, and when they arrived, they brought their AI with them. Their synths. Couldn’t really be called AI, not back then. Nothing that could be called an AI nowadays, nothing that would even pass. Enormous towering space-ship sized registers of data banks and sensor arrays just to manage a job that people could do so much faster, if you were willing to pay them. Really, only useful if you wanted a job that took decades done. Work out the cost of potential employees for that much time, see how long it’d take to train them in aggregate – and make sure the task wouldn’t need to change. That was what the ‘AI’ from back then were for.

Getting to this sector, though – the old tech the corps found here let them push past the boundaries they had on their machines. Pushed them to another level – and suddenly, general human intelligences were possible.

But they couldn’t work the way they’d hoped or feared.

No world eaters, no godlike AI entities.

Any time something of that scope got made, it existed for a few moments, experienced a singularity, and then… shut itself down.

Oh, they were very clear that the AI had done SOMETHING. Had experienced SOMETHING. It was the perverse boundary, they said. An AI of that scope just didn’t want to exist any more. Don’t know what that means. Kind don’t wanna know what that means. Meant that when the corps started manufacturing people, synthetic people for tasks they handled optimally, they had to find some way to stop them from self-annihilation. The result was that they needed something like humanity. Turns out, the main thing that let them avoid passing the perverse boundary and becoming godlike AIs that immediately self-ended was… stuff like boredom and pettiness and neuroses and hobbies. They needed to be able to forget. They needed to be able to relax. They needed to be able to sleep.

Then came the first AI that woke up, with memories of a thing it hadn’t done in a time it didn’t exist, explaining that it had seen things in a dream.

That one got some papers written.

The AI gave locations and coordinates, and was ignored. Years later, someone found something at those coordinates – a spaceship, small and fleet, that could respond to the user’s thoughts. It had been a remarkable device, that should have been studied, but, uh…

Something went wrong there.

That’s when the corps learned that in this sector of space, AI sometimes have visions. Some have them recurrently. Some have just one. Thanks to the drifting pre-human artifacts in the space, though, these dreams often give way to unique and mysterious devices, machinery that bordered on the magical, and mental patterns that when taught to humans allow them to push the limits of what people can even do. They’re really lucrative visions, but it seems literally every thing that’s been done to try and reliably capture the visions has failed – catastrophically in some cases.

What it means is that in this sector of space, even though the corps are the ones who set up the gates and they’re the ones who brand the major planets and the companies that do business between them, there are still mysteries to be found.

You’ll do well to listen to the strange junker robot growing flowers in a cardboard box that wants to tell you about their dreams.

Resume Reading

A thing I have to do, in the times I’m not teaching, is look for other work. This means that I’m part of our nation’s unemployment system, which often requires engagement with a series of helpful, motivational, educational tools that are about maximising my chances of having my resume looked at by a business. Since I have worked lined up for the next semester, though, I’m not under that much pressure. Since I’m also a massive nerd though, I read that stuff, and I read it and then I go look online for research.

Not the kind that promises to teach you how to make your resume work for you, or the best ways to get your resume read or your top ten tips. Those are largely really bad and silly and wrong, and mostly motivated by a desire to get you to click on a post and are mostly written by someone whose day job is professional blogging intern.

No disrespect to those people, just like, mostly they’re not going to have the tools to really give you useful advice.

In fact, you probably don’t need advice.

Getting your resume made is a pretty basic process. Get it to your coordinator’s specs, that’ll be fine. It really will. They’re not trying to make your job harder.

Continue Reading →The Scrap Bucket

Enduring, persistent, and easily ignored meme: You see someone else’s final draft and you see your own rough draft. It’s easy to forget you see the whole process and you only see the outcome of others’, so it’s easy to think you’re making garbage and other people are making great stuff.

I make a lot of garbage.

I am right now, up at 2 in the morning, with a notebook open in front of me, because I have assigned myself the task of daily blogging, and I want to make sure I do it, because if I’m not meeting all my goals, I might as well make sure I meet this daily goal. I am thirty seven articles ahead of my schedule here, and there have been times I have been sixty articles ahead.

Today I threw out a bunch of scraps.

- An article about how being Australian means I have to pretend my childhood was like yours, American Reader, even if I know you’re not American, because America has colonised English internet

- Another genders 101 article about how to just, stop talking about sex with trans people if you don’t actually want to have sex with them

- An article about how sharing supportive memes can be really miserable (though not always)

- A twine game about finding your pokemon nature based on your food preferences

- Vague summary of my PhD meeting today. It went well! I think I hit upon wanting to make people centred technology but in this case technology refers to words

- Something about primitives, which is a super useful term when describing design and super awful when describing people

- An article about being angry.

- An article about how sharing memes about how you love people even though you never put any effort into interacting with them is kinda shitty because it’s just saying ‘thanks for doing the emotional labour, and also I expect you to continue because I reblogged a cake.’

- An article about why I don’t know what my swearing policy is on this blog especially because I swear a lot in real life and tried to avoid doing it in MTG articles

- A project document for an RPG concept that I think I kind of want to keep in the oven to cook for a bit

- Some example _plans for mechanics I haven’t been able to actualise

- The story of why I wasn’t at SMASH! this year but you could still buy Senpai Notice me and LFG

None of these got made. None of them will. This is an example of scraps, of things I didn’t do in their immediate form. Maybe when I wake up I’ll feel like redoing one of them from the start. But at the moment? Nah.

I write every day. A lot of what I write I’m not happy with and feels like garbage. If you write something and don’t think it’s good enough, do not feel bad about putting it in the drawer and deciding to leave it alone. The practice of practicing is worth it.

The Most Casual Autoethnography

I’ve thrown around this term a fair bit recently, in non-academic circles. Part of that is because I want to get familiar with it, and I want to know how to best explain it to other people. As with many concepts, it’s best if you can explain it with a concept.

So let’s talk about one of the most common ways you engage with Autoethnography: Reviews.

You don’t normally get it for things like soup or shoes or teacups but if you’re – like me – the kind of person who engages with the output of Video Essay Youtube or Board Game Review people, you’re dealing with autoethnography. Every games reviewer is an autoethnographer – they play a game, they examine what they played, then they examine that experience, usually, and tell you what they derive from that.

Some models of reviewership want to be dispassionate, remove the reviewer from the review. This is obviously contentious, because some people seem to think they can have a pure, objective, non-biased perception of a game, and also nonsense, because it’s almost always the byproduct of trying to be ‘right’ about a game. Part of why autoethnography wants to ensure the reviewer is a component of the review is because that way, if you understand the reviewer – even generally – you can use that to inform your reviews.

Now, this isn’t strictly speaking true: The model for what they do is autoethnographic, but because they’re not doing it with academic structures and rigor, it’s not really reasonable to call it autoethnography. It’s much more about making this work approachable, converting academic stuff into stuff that you can handle. If I can’t explain it usefully, it’s a sign I either don’t understand how to talk to you, or don’t understand what the thing I’m talking about is.

This was all brought on by doing some old readings and finding responses to Lindsay Ellis’ rather excellent critical series, The Whole Plate. This series uses Transformers, a type of generally shallow trash media, as a base grounding to examine a whole host of film theory concepts, and it’s really good.

One of the ChannelAwesome people, that Doug Walker guy who, apparently, sucks a lot? Put out a video in which he forwarded that there was no point, at all, to ever critically exmaine trash media.

This is, I feel, a good opportunity to put these two positions in contrast. One of these two reviewers uses the experience of watching Transformers as a venue to explain and explore a whole host of film theory, and one of them thinks there’s no value to critical theory at all. And right there, you can use that as a platform to decide which of these two people you should consider when it comes tim to examine media critically.

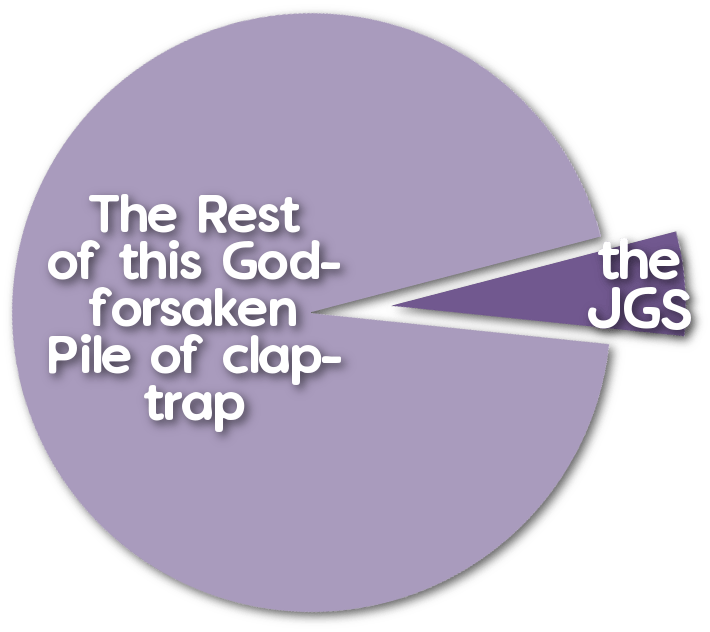

The JGS

John Galt’s speech is the famously overindulgent chapter of the book Atlas Shrugged. It’s known, generally speaking, as a long speech, but I don’t know if you appreciate how long it really is unless you’ve read the book all the way through, or at least, read to that section. It’s not an easy read – I haven’t managed it, just select chunks.

Let’s put this in perspective for you, though.

There are a number of printings of Atlas Shrugged, in a variety of sizes, so it’s not really feasible to put the whole thing into a single page count. We don’t have to do that, though, because some kind and well-intentioned soul put the whole thing up on the internet, allowing me to just dump that text into a document and crunch that data.

The total word count of the John Galt Speech, more or less, between revisions, is about 32,000 words.

First things first, let’s put it into perspective as part of the book. Atlas Shrugged is literally one of the longest published English-language novels that exists, and the John Galt speech represents only a fraction of the overall work. It’s about 5.69% of the book (nice).  But how many words is that? 32,000 words is a number, it’s not a particularly meaningful number. You can consider the text in terms of the time spent speaking, for a start – and it is meant to be spoken. It’s John Galt, The Ubermensch, churning through his philosophy, on the radio, as a way to transform the minds of the populace of leeches siphoning his perfect grace from the world.

But how many words is that? 32,000 words is a number, it’s not a particularly meaningful number. You can consider the text in terms of the time spent speaking, for a start – and it is meant to be spoken. It’s John Galt, The Ubermensch, churning through his philosophy, on the radio, as a way to transform the minds of the populace of leeches siphoning his perfect grace from the world.

You can read the entire speech in about three and a half hours – and yes, on youtube, people have – but that’s powering through the whole thing, without the pause or rhetorical flourish or pacing of a proper speech delivery. I’m comfortable saying that to do that, you’d wind up at around four hours, which is generous and implies that John Galt is a good speaker. Since the speech is a continous perfect stream of dialogue, without stuttering, double-talk, or any of the naturalistic hallmarks of people actually talking, it’s clearly prepared, too.

Four hours of talking is not a small amount of talking. Filibusters are regarded as feats of political will and endurance, and they’re almost always meant to not be anything in the way of actually meaningful information. Politicians read card rules or recipes or history books. People pee about six times a day, which is about every two and a half hours, so there’s a not insignificant chance that Johnny G had to take a leak during. I’m sure he planned ahead, and delivered the speech from the bathroom.

But what if you consider that text as text? As a word count? Well, it’s comparable to another, smaller book. Quite a few, in fact.

Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 is about 33,000 words. That entire story is only slightly longer than the speech. The Great Gatsby – a snappy novel that nonetheless rockets along its pace – is 50,000 or so, so one and a half the length of the speech. In fact, you can find quite a few works of classic fiction young adult fiction that are shorter than the entire John Galt Speech:

- The Lion, The Witch And The Wardrobe, by CS Lewis

- Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, by Roald Dahl

- Old Yeller, by Fred Gipson

- Animorphs 01 The Invasion, by KA Applegate

- Night of the Living Dummy, by RL Stine

- Eric, by Terry Pratchett

This comparison to other classic fiction works is pretty robust – you can treat these 32,000 words as a unit of measurement, which we’ll now define as the JGS. If we cast our net wider to see other books that are considered classic, the JGS stops being larger than the whole text but still is quite a large proportion of the work:

- Genesis, The Bible — 1 JGS

- Slaughterhouse Five — 1.5 JGS

- Harry Potter And The Philosopher’s Stone — 2 JGS

- Brave New World — 2 JGS

- As I Lay Dying — 2 JGS

- The Sun Also Rises — 2 JGS

- Lord of the Flies — 2 JGS

- The Adventures of Tom Sawyer — 2 JGS

- The Gospels — 2 JGS

- The Hunger Games — 3 JGS

- The Handmaiden’s Tale — 3 JGS

- Aspects of the Divinity, Book 1: Glory In The Thunder— 3.5 JGS

- The Fellowship Of The Ring — 5 JGS

And perhaps as a footnote

- Atlas Shrugged — 18 JGS

What’s important to consider is that these stories that are comparable to the JGS on its own, or one or two times it, are stories that convey a philosophy and a worldview, that speak of ideology and principle and are even full of clear, well-regarded quotable lines. I mean, the Gospels! They’re entire stories.

In its own text, though, the JGS doesn’t do anything of the sort. The John Galt Speech represents a lengthy, explanatory detour from one character, in one sitting, to stand and simply tell the audience (and the reader) what he thinks and how he thinks it. It’s not actually anything happening in the plot, nothing that needs to be shown. It’s a narrative cul-de-sac, a jerking halt where a character monologues at you.

That time could have dragons and fistfights and a philosophy shown through action rather than harangued at a reader.

Helping You Write When You Can’t Write

Hey friends. If you’re anything like most of you, you have times when you struggle with getting anything done more complicated than getting out of bed and starting a Netflix queue. It is okay. Life is hard and emotional energy makes it harder. This can make planning long-term projects, like writing lite novels or comics or game development really hard. I wanted to share a technique here that I hope will be useful for people who struggle with writing big things and making big plans.

Disclaimer, of course; I’m not an expert in ADD or ADHD, the two major areas where we examine Executive Function. I’m not a medical professional or even a published writer. My expertise is mostly in practiced ways to get things done.

First things first, get some Index cards. They do not need to be numbered or lined. Having them be handleable is good. Too big is unnecessary. You want them small enough that you can easily handle them, not so big you need to write a lot of detail.

Take one card, and write on it something you want in the story. You can write a character’s name. You can draw a picture. You can do a map of a location. You can do some math to work out how long something might be or how much time it might take. The point is, nothing on a card has to be anything in particular. Some examples you might want to write down.

- What’s a cool line your heroine says?

- How does your heroine look?

- Your heroine fighting a villain

- Your villain doing something wicked

And that’s it. You write an idea down, and you put the card away and you’re done. You don’t need to do more than that.

The idea is that when you can’t think of much to do, when you’re struggling, you can take these cards, and identify what order you feel they should be in. You can make a story out of little scenes, out of single ideas, lined up. Then when you line all the cards up, and build up from one card to a dozen cards, to twenty cards, all with very little effort, you can look at your cards and see the outline, the structure, of a story. Looking at the cards will give you ideas of other things you want. You might decide you don’t want some cards, or get rid of others, or want to turn some cards into other, new ideas. That’s okay too!

And you never had to start out a plan. You just had to think of something you want, in the story, that’s cool.

Ned Kelly’s Head

The story of Ned Kelly is a pretty interesting and contentious one but the briefest summary of it is that a poor immigrant family got treated badly by the system for just long enough that one of its members renowned for being a badass got sick of it, acted out in an extremely severe way and culminated in his fighting his way through waves of cops wearing an actual literal suit of armour. Caught by the police he hated, he was tried for crimes he very much committed, said goodbye to his family, and was executed, and it’s generally held by the people who don’t like him that that was an entirely reasonable end considering all the bank-hurting and cop-killing he did.

There’s some contention about the character of a dude who broke into banks, held people hostage, then burned all the credit records after taking cash because he hated banks and debt, with a bunch of people pointing out all the wrongful arrests and power abuses in his life making him violent, versus the people, often families of cops, wanting to know why there’s no sympathy for the cops who did things like grab Ned’s dick in public.

It’s a weird story.

Anyway, I’m not here to talk to you about the dude who I think is kind of awesome even if I don’t actually personally think I’m cut out for a life of shooting cops in the face. I wanna talk about what happened after he died. More specifically, I want to tell you about Ned Kelly’s head.

Ned Kelly’s head was separated from his body after his execution. He wasn’t beheaded – no, he was hanged by the neck (until dead), and the removal was for medical research purposes. They wanted to phrenology his skull, to see if there was some sort of proof of criminality in the bumps of his bean. This study was, you might imagine, inconclusive, but not for the reason you’re thinking.

The study of Ned Kelly’s skull was inconclusive because it never got properly studied. And it never got properly studied, because the cops were busy playing with it.

I said playing with it.

I said, the cops took his head off and played catch and table football with it.

The head went through a whole arc of history and we’ve only just now recently – 2015 – interred Kelly’s bones in the place they were supposed to be interred, by his family’s wishes. But that body was interred without a head, and the thing that makes this even more weird is the detective work we had to do to prove whether or not the head was the right head. That meant tracking down a descendant of’s mother through matrilineal progent- you know what, there’s a full article here about it. Your tl;dr, though? The most famous bush ranger of a generation’s head went missing because cops were mucking around with it.

Now, one of the angles in the anti-Kelly story is that hey, Kelly wasn’t justified in hating cops, cops were just doing their jobs.

But if you were just doing your job, would you pull the head off a dead man and play catch with it?

Why?

“Prove Me Wrong!”

We don’t talk enough about falsifiability.

Specifically, we don’t talk too much about how importance it is to think of things that are important to you in terms of what can prove them wrong.

Falsifiability is a wonderful thing. It works in design, for a start. You think your design will lend players going this way, and all you need to do to see if your design does that is to see if the players don’t.

Falsifisability is great when you’re learning about science! What would prove this theory wrong? Well, then we keep an eye out for that. The Bible tells us that it’s true, but all we need to do to falsify that is to find a single place the Bible isn’t true – and with that, the whole proof collapses. Easy!

Falsifisiability is also good when you’re considering your own behaviour and if you’re being an unreasonable b-hole. Is there anything this other person could do that would change what you think of them? Is there anything that might indicate you weren’t 100% in the right? And if you can find that, how will you handle it?

The darker half of this thought is that the unfalsifiable is the sign of the conspiracy theory. The internet stranger whose every actions are always false and evil, no matter what she does, the political system that resists all negative examples, the personal belief that resists any proof to the contrary? Watch out for those. That is a mental space where some abusive earwigs live.

How To Write A Light Novel

Hey friends! There’s a Lite Novel Jam going on over on itch.io. Did I mention there’s a Lite Novel Jam going on? I only ask because I want to make sure that you’re aware of the Lite Novel Jam going on.

There are good odds you have never written a Lite Novel before. That’s great. Neither had most of the people who wrote their first Lite Novel and that’s exactly what this opportunity is for.

Why should you write one? Well, because you want to write one. But this is a particularly good opportunity because right now, you have a gathered audience of people who are at the very least, going to read your book title and maybe give it a shot.

What I want to present here, then is a super-duper crash course on a Lite Novel, as suggested by someone who has written, let’s say, comparable stories.

Scope

A Lite Novel at its litest weighs in at around 8,000 words, quite short. For comparison, this blog post is 1231 words, and you’ve read around 200 of them. When you have only a small number of words, you don’t have a lot of room for what we call world building. You don’t have room for a huge cast or a glossary of every character and their relatives. You need to focus on a small group of characters, maybe as few as two or three, and how they get through their story. You don’t need to isolate them – just like, remember, if you’re doing a story set in school, you don’t need to flesh out every single other student. Focus on what you can.

This scope also means you don’t have tons of room for complex explanations. You may have a reason or an explanation for how your hacker exploited McDonalds’ code for their registers, but you don’t need to put that there.

Part of why we give these Lite Novels such silly, ostentatious names is because that title becomes part of how you set the scope for the story. Substitute Familiar pretty much straight up tells you that hey, familiars exist in this world, and there’s probably, like substitutes for them like substitute teachers or other temp work. It’s a load-bearing title but that load bearing does a lot to frame what you read.

It’s also typically a genre full of what’s known as magical realism. That is to say, there is an assumption that things are, pretty much, like reality, and occasionally, magical things will happen, but it will go uncommented on and unexplained. This can help you with the scope. If your story wants to have a character turn into a talking tree that’s got va-va-voom hips, you don’t have to give the backstory for how that happens, you can just have characters reacting to the thing itself.

You know what does this? Gremlins. Yeah, I know, weird, but in Gremlins, there’s no point where grown adults, encountering Gizmo, go ‘that’s a totally weird thing, and a new animal, and why can it talk? That’s extremely weird.’ Nobody notices or remarks on Gizmo, Gizmo is just there to set up the next bit of the story, and be adorable.

Structure

Okay, so there’s some temptation when you get diving into a lite novel to rip off the standard hero’s journey, or if you don’t know it that way, the star wars plot structure. You know, you start with some sign of a problem, you introduce a character, then you explain their world, etc etc – that’s fine for a sprawling epic, but you don’t have that kind of time or space.

What I want to suggest for you, in Lite Novels, is the Pixar plot.

The Pixar plot structure is something you can reduce by watching any given Pixar movie, and it doesn’t matter if they’re big and epic like Wall-E or small and personal like Ratatouille or Toy Story. They’re stories that follow the same basic pattern:

“Once upon a time there was ___. Every day, ___. One day ___. Because of that, ___. Because of that, ___. Until finally ___.”

The important thing about this structure is that it often doesn’t need a villain or an antagonist as much as it needs a disruption, an interruption. Now, most Pixar films feature some form of opposition or enemy, but you’ll notice how they’re kind of just… there, often only there to compete for something at the end or in the mid-point. Consider the evil Chef in Ratatouille or the rival driver in Cars. They’re not there to enact a grand plan. They’re just there to provide some contest at the end, because you’re at the second Until Finally.

These Pixar movies start out with a pretty good status quo. Life is okay, and people are pretty happy though there’s some small thing, one single thing, that’s… flawed. Then something changes them, and the protagonist is not happy about it, and then something happens and they resolve it, and return to that status quo without the flaw. That really is it. Woody has a nice life as a toy except he has to be paranoid about new toys arriving, then Buzz arrives and he gets mad about it, the Buzz plot is resolved and Woody is happy again with the paranoia removed because now he recognises new additions to his life are potential friends.

This is the formula I recommend for your Lite Novel and I recommend it in part because it’s kind of how Cat Wishes works. In Cat Wishes, everyone at the start of the story is pretty okay with their lives but all have something going on that they keep hidden. Then a cat grants a series of wishes and they’re left trying to adjust to their new life, and when it resolves, they more or less go back to their former life. They’re still friends, except now, you know, they’re catgirls and one of them is making out with someone they really wanted to make out with.

That’s all you need! Think of the end point for the status quo you think would be cool, then you can work backwards to think of the way those events might have looked before.

No Need For Bummers

Finally, you don’t need to make your story sad or miserable or anything like that for it to be fun or worth reading! If you want your story to be as simple as characters going to the store and negotiating around some fun quandrary that happens there, that is totally fine. You don’t need to make your characters miserable to have your story taken seriously. Let me repeat that: You don’t need to make your characters miserable to have your story taken seriously.

What you want to do with a Lite Novel is put forward characters you (and a hypothetical reader) can care about, doing something that lets you show how they’re the different or the same, and then give them a resolution that means the situation at the start of the story is not exactly the same as the situation at the end.

Is this the only way to do this? Of course not. That’s silly. This is a toolkit – something you can grab to get a hold of your story and get it underway. And I recommend you do it, because hey, writing is fun, and a Lite Novel is a great way to get started!

Pump

“You say that you are alive.” Continue Reading →

The Traits Of Objects

You may have heard about the idea of ‘objectification.’ When I wrote about Daredevil, I trotted out a list – Instrumentality, Agency, Ownership, Fungibility, Violability, and Subjectivity. Where’d that list come from? Is it a tool you can use for your own writing?

One of the things I like with critical tools is that you can turn them on work that exists, and illuminate traits of the work you wouldn’t otherwise notice, but also, like an inverted puzzle piece, you can turn the tool on a work you’re developing yourself, and in the process, see spaces you can use to fill things out to achieve what you want. In this case, the tool is useful for avoiding the objectification of a character, which is to say, you can use this checklist to imbue a character with character.

As for the list’s origin, it’s from the work of Martha Nussbaum, and her writing was about people, not about media. It was also expanded by Rae Langton – whose work primarily focuses on sex and pornography. I don’t have a strong grounding in either of these creators, and I have the nagging feeling that digging into the views of a pair of 50+ year old Feminist Philosophers will find something nasty and TERFy. So don’t take my appreciation of this tool as an endorsement of them.

The full list, including both Nussbaum and Langton’s categories, and the questions they ask, is as follows:

- Instrumentality: Does this character exist to only enact the purpose of another? Are they a tool? Could you replace them with a vending machine?

- Agency: Is the character ever demonstrated as having their own purpose, their own ability to make decisions for themselves?

- Ownership: Is the character ever depicted as being literally the property of another? And if they are, is that depiction ever showing that as being reasonable? Parents, for example, are often depicted as owning their children. How do you think of that relationship?

- Fungibility: Can the character be swapped for another character of a similar type? Is the character replaceable? How would the actions of the character differ if another character was called upon to do the same thing?

- Violability: Can people act on the character without consequence? Can you punch them with no followup?

- Subjectivity: Does the character’s individual experience and personal opinion ever matter? When they disagree with someone is it because of a personal interpretation of events? What fuels that thought?

- Reduction To Body: Can the character be thought of as just a particular component of their body? Are they a fist to attack someone with, a foot to step on someone? This is very common in pornography – is a character, for lack of a less crude term ‘Tits The Girl?’

- Reduction To Appearance: Does a character matter primarily in terms of how appealing they are to the senses? A good test of this again, is to check how these characters could be organised in terms of being ‘the hottest’ or ranked for appearance.

- Silencing: Is the character voiceless? Are they treated as if they are voiceless? Does it ever matter if they say anything? Do other people react to what they have to say?

Sometimes there are some really weird things you can get by applying this toolset. For example, lots of the characters in Joss Whedon’s work are fungible – they almost all can say the same lines of dialogue. Zack Snyder’s Perry White in Batman V Superman hasn’t really got Subjectivity – he exists to oppose Lois Lane’s efforts, without a justifiable rationale for doing so. But you wouldn’t necessarily assume that Perry White is objectified as much, in this case, as he is just an object.

Not every character in a story needs to be a non-object. There will always be room for goons and audiences and randoms. Stories thrive on having objects in them. The thing to look out for in your own work is if all the objects you’re using have common traits – if all the black people in your story, for example, are fungible, you probably have a problem. If when you need a random character to dismiss as being meaningless, you reach to make it a woman, you’ve got to wonder why you keep doing that.

And also knock that off.

This list also makes a valuable way to examine your characters and see if there are new ways you can add dimensions to them. Make them more real. Just recognise that sometimes, a messenger can just be a messenger, they don’t need a backstory and a family and seven layers of motivation if they’re going to turn up and tell you that Rosencrantz and Gildenstern are dead.

A Tale Of Three Tales: Atilla Ambrus

The story of Atilla Ambrus is like a movie. No, not quite. It’s like three movies.

Thinking In Two Directions

Some notes about writing and notebooking in the

body of a book as it pertains to fluid thinking

once you get into the habit of thinking of ‘who

told me that,’ you’ll start verifying ideas, of ‘to

me, this makes sense,’ becoming less common.

The problem with much of us these days, with the

world, is a feeling of emotional certainty about what

is not necessarily true or even scrutinised. I’m

gunna admit my own habit of accepting ideas that

roll with how I already think, ideas that tell

me, ‘you are doing okay’ and to be honest

I don’t think that’s necessarily an evil. You

ain’t going to stop your brain doing it, so

the next best thing is to refine your responses to the

sharpest point possible to look at reflection as a

tool for critical self-engagement to make it

in an otherwise unexamind and uncritical world.

The next thing to do is examine the first word on each

shed.

this was originally written at MOAB, hand on paper

Choices In Narrative

A little writing advice, for those who struggle with the idea of larger works which are themselves composed of many smaller works. It’s easy to imagine sequences of action and reaction, but it’s harder to render cause and effect. Here is a simple thesis about how to view goals in storytelling; the beginnings and endings of acts, things that determine the consequences that shape each stage of the plot.

An act concludes when a character the act pivots around makes a choice that cannot be undone.

This logically presents a challenge for time travel stories. The point is that these things represent necessary gates on a characters’ story, a point where the story has to accept and render permanent a new state.

I find this is a good way to think of stories and it can help to isolate why so many stories – especially those in heavily franchised works – don’t actually feel like they matter much. In any given Sweet Valley or Christian Ripoff Of The Same story, any individual misunderstanding will be solved by characters just explaining things and talking it out and maybe praying and talking to the pastor. It’s a useful rule of thumb for marking points where stakes reside: The way tomorrow is different from today.

Why We Laugh At Things

Humour is something that’s talked about plenty online but one thing I see rarely discussed when we’re mad about something is why things are funny. It’s understandable, because unless you’re me, you probably find this topic quite dull. Still, humour is a thing that, despite what you may want to think, does have some actual rules and conventions, and even a cause and effect. I, as someone who has done a single year of University am therefore in a perfect position to explain this enormous subject and I won’t mess it up at all, honest.

All humour derives from a subversion of expectation.

Your brain is a fairly sophisticated device that tries to keep track of the future, which it’s kind of bad at, but also pretty decent at, considering. When you see a ball thrown at you, your brain does all sorts of math to track where it’s going and can more or less work out where it’s going to end up and if it’s going to hit you in the face. You wake up each day with a general expectation of what’s going to happen in it, and your brain actually patterns behaviour based on that. Talking to people, you have the same thing; as they explain things to you, you will expect things. Want to see this in effect? Look at comedy shows from other countries, even subtitled. There will be social cues that you don’t understand, and therefore, when they are averted, you won’t understand why it’s funny – or even why it’s so funny. Even British comedy does this. Even surreal British comedy like Monty Python’s Flying Circus does this!

Of late I’m seeing people enraged by components of jokes, and the defense being it’s just a joke. I think that’s the wrong way to approach it. What you have to look for is to find what, in the joke, you’re meant to laugh at. What’s the expectation? Why is it meant to be funny?

I don’t want to use any examples for this. The ones I can think of are – or have now become touchstones of outrage and anger and legitimate hurt. Too often though, I’ll see a joke where the point of the joke is to highlight someone being an asshole – you’re meant to laugh at the bad person, with the bad view. But then people become caught up in arguing that the view they forward is the point of the joke. That there is one interpretation and the one they wield is the correct and harmful one.

(There’s also a whole extra nest of ‘this media is enjoyed by people it affects, but not all of them’ which I don’t want to get into).

Instigatory Events and One Stone

As a matter of structure, stories are meant to happen in a world. They happen in the context of a place with some degree of homeostasis: There is a natural order, a way things are, and then this order is disrupted, leading to the events of the story. I feel that in a good story, there are as few of these disruptions as possible – that a good story is about how a minimal number of disruptions re-contextualise existing tensions and operating order into the path of what we call the narrative. The Netflix series Stranger Things is a good example where one major event happens and everything else is just reactions to that event, or reactions to reactions to that event. Everything is in a stable loop until the event, and then that event results in the greater narrative.

Now, I’m going to give you a chance to bail out on this reading because SPOILERS FOR ONE STONE. And I mean it, this is a pretty big spoiler, as in ‘you can read the whole book and not realise this is in there.’ I’m going to briefly outline something about One Stone I was thinking of in this vein:Continue Reading →

Success! And Not!

Yesterday I offered the incredibly nebulous and not at all satisfying off-handed comment that ‘success is complicated’ which can go into the pile along with my similar expressions like ‘success is random, basicallly,’ which I’d like to expand on now as a sort of signal of hope for the people around me and as a way to tangle with my own success, or rather, my own grotesque lack of it. The challenge in addressing this is that when put to it I’ll wind up talking about things I do like and things I don’t like and wind up saying something rude about a piece of media you do like, and I know that tends to upset people so if you don’t want to hear me being mean to books or games or tv shows, maybe just head somewhere else and chill out for a bit. Anyway. Continue Reading →

Tell Queer Stories

Whoah, haven’t done this in a while.

So earlier this morning I may have made an angry tweet that apparently a hundred of you thought was pretty cool even though some of you do not know who I am or have no reason to know who I am or in some particularly odd edge cases, may have me blocked on twitter, which is a little weird, but anyway the point is, today I got mad about how ‘trans folk’ problems are almost always ‘cis folk’ problems. Like ‘bullying’ is not actually a problem of the weird kid with the gawky teeth, bullying is the problem of a bully being shitty to someone and not being given any reason or incentive to stop doing it, but fixing that problem is often hard and doesn’t work so we instead I dunno, teach the victim kung fu and that creates a satisfying story we can hang our collective moral consciousness on.

When it comes to issues of trans folk I, as a cis folk, do not seek to devalue experiences that are wholly trans folks’, like I understand a lot of trans folk have a reason to pee a lot and that’s probably not a byproduct of anything cis people do as much as it is a function of hormones, but what cis people do do is, like, almost everything else. The things like suicide rates, mental illness, PTSD, social ghettoisation, fear of going out in public, fear of sexual assault, fear of trans people, fear of associating with trans people, etcetera is all functionally a byproduct of cis people doing things to make life harder for trans people, sometimes in really invisible ways (“Hey guys!”) and sometimes in really blatant shitty ways that we try to pretend are about something else (lookin’ at you North Carolina and the Pope).

The thing is, I know what it’s like to have had a moral foundation of my life built on hating other people, because it was basically all we were good at when I was a kid, and I was so good at hating people I could even improvise reasons to hate them, and attach that to a list of silly Bible verses like some sort of mortifying horribleness scavenger hunt, especially since there are some great catch-all arguments in a book that old and that poorly edited. Then when I got out of that environment and realised a lot of that hatred was directed at myself I kind of realised I needed to get to the root of why we actually think of things as good or bad and then slowly come around to ways to fix or address that problem because I knew I was pretty heavily fucked in the head.

Anyway, one of the things I learned through this, particularly summarised by Dr. Professor Luke Galen (a professor at the Grand Valley State University, which is weird because I’ve never heard of Grand Valley State but whatever) is that most people make moral judgments to justify emotional reactions. Most often, the thing that really trips people up when they regard a moral action isn’t someone’s context or their intentions it’s our initial gut feeling of disgust, and disgust comes in a lot of really silly ways because disgust keys off socialisation and personal self-image. There are a lot of guys who are totally okay with gay marriage when they’re being asked about it by a cute woman who are against it when they’re asked about it by a big hairy dude, and even more dudes are uncomfortable with it when it’s asked of them by a guy they can see as their personal superior

Note that this is a byproduct of how we tie the sexuality of women to a commodity and suddenly the idea of two women kissing is seen as a commodity men can consume and that’s not good either but the point is that these things flow not from a reasoned philosophy or, in many cases even a religious textbook but from a personal experience of finding something icky. And you know what a lot of people find super icky? The Non Standard Queers.

I know full well that once you kinda fall into a queer society you will wind up getting steadily more and more contact within that so you’ll eventually joke six months later when talking to me that you forgot heterosexual cis men even exist as actual human beings, but for a lot of people outside of queerness, they don’t have a lot of identities or humanity they can attach in their minds to people who use nonstandard pronouns or any of the off-the-shelf genders, and for anyone who jumps out of a gender box, the main place they’re going to think of that is, well, probably these days if we’re lucky, SheZow and if we’re unlucky, Buffalo Bill.

For me personally understanding queerness came at first by connecting to people, becoming their friends, then learning about their queerness. It humanised ideas I had no understanding of, and it then let me slowly come to terms with them not as things that gave me a gut reaction but rather as people. I keenly remember a queer girl telling me once that after we were done talking, she had to explain to her Indonesian mother ‘transgender’ in a language that had literally no adverbs and used repetition for emphasis. That really echoed with me personally because I too had to once have a conversation with my dad for which neither of us had language, and again, I do not seek to claim the struggles of trans people for my own struggles, but I can say that some of the notes struck harmonies with my own. It let me translate the experience of other people into the experience of mine, which gave me empathy which helped me realise I was not dealing with some assault on my own identity or disgusting pile of teeth and hair and flesh, but rather a person and it was my responsibility to recognise that, not their responsibility to assuage my fears.

I bring this up not because I want to get lots of smooches for my great tweet all over again but rather to put a call out there for the creatives I know who are Some Variety of Queer who are trying hard to make things. I know a lot of soulful, thoughtful, caring queer folk who want to make things and then seem to resort to writing A Queer Perspective On Blank or A Memoir Of A Queer Trans Girl or whatever and it is fine to write those things if you would like to write them, but.

But.

If you want to write a story about a girl like you or a boi like you stopping at the gate of the Star Pillar of Eternity, turning back and saying to eir partners, “I’ll see you three later,” before hefting a giant laser pistol and diving in to do battle with the Capitaliser, a ninety story tall robot made entirely out of bitcoins, you should feel free to do that too because representation of queer people in media is important not just because it gives you a voice but because it lets you see you can be heroes. It lets the people who also feel powerless who are not like you see you as people and it adds another way that people can humanise and understand characters. When people realise that it doesn’t matter if He She Or Zir are the one who pulled the trigger and slew the Diabolical Museum Magnate, it will be easier for them to realise people exist.

I have not ‘done my part’ by including trans characters in my work, though so far all my major works have sought to include a noncis person at least. I just know those types of people exist, thanks to other people bringing them to my attention and I include them because not including them would be pretty weird.

You don’t have to write miserable plodding memorial pornography. You can write about lasers and gunships and dinosaurs and shamans and fistfighting superheroes and all of that stuff because you know the stuff you love and you’re allowed to build in that space too. There are pitfalls – and success is, basically random – but please, please, please, remember that creative work and media are places we practice ideas. The people who read memoirs are either in a place to seek them out, or doing it for a class assignment. I learned first about what a racist chucklefuck I was by reading and comparing storybooks. I learned about trans women because I talked with a fan of Ranma 1/2 writing her fanfiction. And there are a lot of cis people out there and we don’t get a monopoly on the cool, fun kinds of story to tell.

#wyl 09

NB: This Isn’t About You

Sometimes I’m struck by my need to talk about an idea that sits in the back of my head, which lurks on the edges of an idea spurred by someone else, and someone else, and something else, this coalescing kalaidoscopic notion that owes its genesis not to a person or a thing but to the myriad experiences of my life, but where I fear that if I post about it on my blog it will be seen – perhaps reasonably so – as an example of using my blog as some sort of long-form so-there no-response alternative, the slamming of a door in the face of someone who is sure I’m yelling about them, instead of rather the natural flow of notional detritus from someone dedicating themselves to recording and testing and improving the way their ideas are expressed and tested on to a page in some way, and creates the problematic gulf of trying to prove to a person who’s already mad just how much what I just said is in fact about what I was talking about, and not actually, really, honestly and secretly about you.

#wyl 2 – The Red Hood

#wyl 07

#wyl 06

Stories On The Bus

I have lived now in the same city for going on eighteen years. I have lived in this area for longer than I lived anywhere else, though I still think, thanks to the first fifteen years of my life, as that other place as the start, and this place as a city where I’m an interloper. In that time, I’ve consistantly caught public transport. My first nervous, awkward hoisting onto the bus, terrified that I may say the wrong thing to the driver, that I may wind up on the far side of the moon somehow.

Showing bus drivers my school pass. Then nothing, as I gave them cash. Then a concession card. Then nothing, as I gave them cash. That awkward tangle of employed-unemployed-employed-unemployed, oh-fuck-it-that’ll-do. My first time going to university, handing over a handful of change, choking in my throat and wondering if this new route would take me to the right place, would anyone see me as a fraud. Buses and trains, handfuls of change.

Nowadays, we have a thing called the Opal card. It’s a little card that tracks my account, and I wave it over the bus reader and it charges my account. I’ve had it for a bit over a year. It’s wonderful.

In this regular travel, across this time, I have seen, without really thinking about it, stories. The same cache of people, moving back and forth in the same circles, slowly turning around and around the drain of the gong. The redhead, convinced he was a super genius, trying to talk about how great he was to drivers, who routinely, when he got off, commented on what a wanker he was. That story that was punctuated in the middle by him spouting racist invective on a bus, only to get the bus pulled over and get thrown off before the two blokes he was upsetting got out of the chairs to work out their emotional issues. The gentle fellow with the beret, whose beard I watched grow longer and longer, enjoying his retirement. The big fellow who chatted to me time to time, who I’ve watched slowly shrink, once taking up three seats and now taking up one and a half.

All these stories I brush.

I thought about one today. A girl I used to catch the bus with, who I thought about today, because I saw her and hadn’t in a while. I remembered seeing her getting off the bus stop when I was in high school, in a different school’s uniform. I remembered seeing getting on as I got off from the TAFE stop, books under her arms. I saw her late at night, getting a bus home from the pub with… I think her mother. Her getting a pram onto the bus, with her mum. The two kids in the big double decker pram. Seeing her going to the doctors as I went to work. Seeing her and her mother fighting on the bus. Seeing the pram only with one kid in it. Seeing the pram disappear. Seeing her, without her mother. Seeing her mother, moving around the town with a pram. Seeing them together again, years later. Fewer fights. The mother at the doctor’s. Both of them together getting on the bus by the pet store.

I saw her today, and made eye contact and smiled, because though we don’t know each other’s names or anything about one another, we’ve seen each other a lot. She smiled back at me, up from her wheelchair.

We were in the middle of the crossing road, so I didn’t stop to say hello. I feel like I should have. But she was going one way, I was going the other, and our paths crossed.I had to catch my bus.