Values of A Dollar — The Confederacy’s Currency

Hey, the Confederate States Of America were a racist slave state that was founded in the name of maintaining a white supremacist state forever, and its eventual fall was a moral good. But don’t worry, while that state existed, they also made a bunch of shitty, self-glorifying art that even when it’s technically well crafted, is all built out of a fascist, white supremacist ideology that was so bad and so obviously evil that even The United States was their moral superior. Whatever aesthetic value their culture has is, like the art of Rhodesia, entirely predicated on them being a nation whose significance in modern culture is entirely about clinging to an ideology of racism, and you do not, in fact, got to hand it to them.

Anyway, I think that sets the tone right.

I have said, many times, that your culture’s money is probably the most commonly reproduced piece of art your culture makes in your name. It is the ideology of a nation, in its most common piece of civic art, art that’s meant to represent who you are and what you value, and that’s why it’s meaningful to care about what it depicts. I’ve said that the United States currency is some of the worst, both in term of its accessibility, but also its devotion to depicting nothing but the institution of its own governance from a very narrow window of time. Basically, US money depicts nothing as much as it depicts the importance of a small handful of people who maintained and operated the mechanisms of creating the country of America.

They still have Andrew Jackson on a bill and they’ve had seven years to put Harriet Tubman on a bill, and that hasn’t moved past prototype stages, so you can see how important it is to the people making choices.

But that’s America America; what about America America America, the America that insists it’s even more America than America America? What did the Confederacy put on their money?

Continue Reading →British Currency

Years ago, as one of my research projects, and to show off a bit, I talked about Australian money, because Australian money, unlike most other cultures’ money, is good, or at least, better than yours, or, most importantly, better than America’s, which is really bad. At the time I had the fanciful idea of maybe examining a bunch of different culture’s money, but mostly they all repeat the same basic-ass mistakes as the American money, which I think is possibly because American money is the template a lot of other countries use (why).

Still, there are at least two other countries whose money I think is worth talking about, and we’re doing one of them today: the British currency. Talking about Australian money took a long time, weeks, with stories about every figure involved. Talking about American money took a short dismissal, because all American money is bad.

British money needs a little bit more space, but less than it should.

Let’s go.

The Values Of A Dollar: American Currency

I promised myself I wouldn’t just throw rocks at US currency for being bad, because let’s face it, most things in America can be pointed at as being a little bit crap. I could make articles for days, standing outside the United States saying look at what this asshole does or look at how this crappy crap works, isn’t it crap, and I don’t wanna be that guy. But.

Currency is a practical element of an economic nation, and that’s fine, I mean, if we’re going to have it, we’re going to need it, and I’m not going to get into Hill People conversations right now. But currency is more than a purely pragmatic piece of government infrastructure: It is the most commonly produced, reproduced, and seen artwork that a nation has. Currency lets you reflect, to your citizens, in everyday ways, things that matter to you all. It is one of those places where media and community can feed into one another, and thanks to their passive practical application people will slowly, osmotically internalise the importance of these figures.

Don’t get me wrong: Australians broadly speaking do not know the people on most of their currency. But when you use their names, they often can attach those names to people.

Now, I want to start complaining about American currency infrastructurally (why do you still have pennies and dollar bills and cotton notes you galloping goons), and there’s a time for that, but let’s not, and instead I’m going to talk about what’s on the notes. This is easy, compared to talking about the Australian notes, because the American notes are kind of churned out to a really basic theme.

Now, I’m just going to focus on the common circulation bills here: The $1, $2, $5, $10, $20, $50, and $100 notes. There are some bills of higher value than that, but they are silly, and dumb, and let’s throw rocks at them.

Anyway, in order, those bills feature on their front faces George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, Alexander Hamilton, Andrew Jackson, Ulysses S Grant, Ben Franklin. On the reverse, they feature The Seal of the United States, the Declaration of Independence, the Lincoln Memorial, the Treasury Department Building, The White House, The Capitol, and Independence Hall.

Now, this basic structure was picked in 1914, and has only been slightly changed since then (like, the bills shrunk). The people on bills can be basically broken into two major historical beats: The Civil War (Grant and Lincoln), and Founding Fathers-Era Stuff; early presidents and signitaries of the Declaration of Independence.

And… Andrew Jackson.

Andrew Jackson. What the fuck.

Content Warning: Following video contains some insensitive ways to describe what might have been mental illness or may have just been some gigantic asshole:

Andrew Jackson, in case you weren’t aware, is basically the kind of thing the Constitution was meant to prevent happening. You can scratch this pyramid of a life and see that every layer down reveals something worse. It wasn’t enough that his Presidential Inauguration party was so raucous he had to sneak out, fill bathtubs on the lawn with whiskey and then sneak in while his revellers ran out onto the lawn and get more hammered there. Andrew Jackson used to duel as a hobby – and no, I don’t mean he liked to fence, I mean he liked to go out behind the actual White House and shoot people in the face over ridiculous slights. At least once he was actually shot and responded by killing the person who shot him. This was while he was President. Jackson used his last days in office to recognise Texas as an independent country because he didn’t want that pro-slavery bastion of anti-Mexican sentiment to be ignored by an anti-slavery president coming after him. He committed actual acts of genocide, and I mean he was personally there, a lot, killing people. And then, as if to just add a little dash of irony, he didn’t want America to have banks or banknotes.

Why the fuck is this guy the special exception!?

I mean, set aside that the guy was a total raging asshole, then set aside that he was a complete fucking monster, and then set aside that he didn’t believe in money, you have to be able to value other stuff this guy did a lot more than things like not-murder, not-slavery and not-random-acts-of-pointless-violence. And that, right there, is kind of the problem with all these money people.

For the most part, these guys are notably, historically, for their part in creating America, or, more specifically, creating American government. Government that, again, see back up the top of the document, is at the very least, a little bit crap. And the reverse faces are all… monuments to, or instances of government. The lesson then, in the simplest possible way, is that the US Government wants Americans to think of the most artistically relevant part of their lives as, well, the US Government, but the US Government as expressed and represented by the historical context of old white slave owners signing documents and huffing about not paying taxes that they, themselves, were responsible for incurring.

But you know what else is interesting in this? The money, in its basic template, has been the same since 1914. The money is designed to evoke a timelessness, an aesthetic of ages and represent things that also do not change. So you have this common artwork that holds fast to history, if you can ignore all the ugly bits of history, and then emphasise them as important in their shaping of the aforementioned slightly crap system…

And then consider how Americans are resistant to systemic change.Consider how every American, every day, looks at art they are told is important, they associate with importance, and with living, that is of old dead men focused around one narrow window of time, doing one narrow band of things, and … okay, one total fucking maniac in the form of Jackson. You even have an example of change in the notes – Lincoln and Grant! They had a civil war, and that’s what it took to free slaves, because this country is that resistant to change, jesus christ.

What I’m saying is: Art of a culture reinforces and influences that culture’s attitudes, and America’s most common art is about how America, as it is, is totally fine, and stop complaining or trying to fix anything created by these divine flawless old guys.

And now

NOW

you’re thinking about adding Harriett Tubman to a note. On the obverse of an Andrew Jackson note, possibly? Because man, that’s not awkward – a man who murdered people for fucking fun as opposed to one of the great icons of humanitarian risk? A man who hated how people made a big deal about his pro-slavery views on the other side of a note to a woman who was a former slave?!

What the hell?!

It’s nice to put Harriett Tubman on a note. It’d be good too, to strip off the people who wrote about ‘all men created equal’ while they were treating women and black people like awfulness. But that’s the real gist of it: This is nice. There’s more to do. There’s a lot more. A lot better.

Also, there’s the possibility you don’t want anything to do with money and you find the idea of putting art of Hariett Tubman in every pocket across America as gross or vile because it’s part of capitalism. I’m not about to say that being against money is a bad thing, but I do feel like at least, right now, it is a part of art and culture.

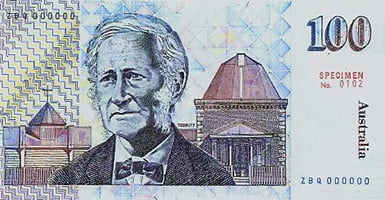

The Values Of A Dollar – $100

And now we come to the very last of the Australian bills. We’re almost done with this little tour of bills – having already done 5, 10, 20 and 50.

John Tebutt

%27%20fill-opacity%3D%27.5%27%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%235e5e5e%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22rotate(157%2052.9%20101.8)%20scale(116.11463%2070.52669)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23dedede%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(-72.49609%2035.81668%20-167.91804%20-339.88079%20351.6%2082.8)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23d8d8d8%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(-30.67631%20-34.8672%2065.9323%20-58.00753%2021.4%2032.1)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23d2d2d2%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(-15.66877%2027.23514%20-53.8029%20-30.9536%20197.4%2016.2)%22%2F%3E%3C%2Fg%3E%3C%2Fsvg%3E)

The old printing of the 100 featured on one side, John Tebutt, who can be simply desribed as ‘an astronomer.’ He discovered a comet, or specifically ‘the great comet of 1861,’ which was kinda neat, but there was no way to tell the people in the Royal Society in England about it because hey, the Pacific Ocean is quite a thing let me tell you. When the findings were checked and dated, Tebutt was correctly attributed as the first discoverer of that comet, and that’s where most folks’ stories would stop.

Instead, Tebutt went on to hand-build his own observatory near his dad’s home, and spend the next fifty years studying the stars from a position that had been largely untested. The rest of his career was tireless study and publication.

What’s really interesting to me is that in this printing he completes the arc of all of our currency featuring a scientist on it.

Douglas Mawson

%22%20transform%3D%22translate(.8%20.8)%20scale(1.5039)%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23e0e0e0%22%20cx%3D%2218%22%20cy%3D%2268%22%20rx%3D%2230%22%20ry%3D%22255%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%236a6a6a%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22rotate(-93.7%20127.9%20-17.7)%20scale(116.67285%2052.53926)%22%2F%3E%3Cpath%20fill%3D%22%236f6f6f%22%20d%3D%22M82.5%20152.1l3-87%2020%20.8-3%2087z%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23a7a7a7%22%20cx%3D%22233%22%20cy%3D%2245%22%20rx%3D%2237%22%20ry%3D%2284%22%2F%3E%3C%2Fg%3E%3C%2Fsvg%3E)

Douglas Mawson was also a scientist. But instead of building something in his dad’s backyard, he went down to Antarctica to study the rocks there. Mawson’s story of exploration of the Antarctic is sadly one of those stories that, like so many other exploration stories, has tragic and sad components; while Mawson lived to tell the tale, many dogs didn’t, and just bringing that fact to mind makes me sad.

On the other hand, it’s kinda weird that our currency featured a dude who once ate dogs.

It was pretty dire as experiences go, I don’t want to act like he’s a bad person. It’s just sad anyway.

Dame Nelly Melba

%22%20transform%3D%22translate(.6%20.6)%20scale(1.1914)%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23caddd7%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(53.3366%20-26.59265%20102.90272%20206.39092%20219.8%2049.5)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23576661%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(-13.5076%2055.55344%20-94.71297%20-23.02907%2060.8%2075.1)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%2332a981%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(-19.40671%20-1.01192%205.83877%20-111.97641%2012.8%2033.3)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%2341b48e%22%20cx%3D%22239%22%20cy%3D%2230%22%20rx%3D%2227%22%20ry%3D%2218%22%2F%3E%3C%2Fg%3E%3C%2Fsvg%3E)

In the second printing, however, rather than Antarctic explorers, we have Dame Nelly Melba, whose claim to fame in common parlance is the time someone else named a dessert after her, the Peach Melba – a dish ironically that features none of the name she’d been born with, but was for the name she chose. Nelly Melba, aka Helen Porter Mitchell, was one of the most famous operatic sopranos of the early 20th century.

What makes her significant in our history is that there was a point, in all seriousness, where we, a nation that claims to thrive on music and culture and art and poetry and science, were considered a place that could not yield actual artists, could not create actual ‘real’ culture. And from this came a woman whose voice thrilled the world.

Sir John Monash

%27%20fill-opacity%3D%27.5%27%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23c3c2b0%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22rotate(176.3%20144%205.1)%20scale(231.72204%2055.22651)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23307e68%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22rotate(149%20164.3%20122.8)%20scale(144.84461%2066.7313)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23979a2c%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22rotate(-102.5%2088.3%20-.7)%20scale(141.4759%2046.887)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%234fac94%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(-57.0254%20-10.98136%2022.46276%20-116.64747%20420%20112.5)%22%2F%3E%3C%2Fg%3E%3C%2Fsvg%3E)

Monash, whose name most commonly connects to a set of university campuses in Sydney, was an engineer who, when Australia was looking for a general, thought he could do a bit of that warring business. It’s kind of funny to me in hindsight that he, as an engineer, fills out the scientist requirement of this bill – because we often joke that engineers aren’t ‘scientists.’

John Monash was appointed to a leadership position for infantry in the First World War – a position that was met with resistance because this Australian was also a German and also a Jew.

If you know First World War history, the classic line is that the troops were lions commanded by donkeys. We created technology that outmoded our tactics; monstrous machine gun nests which we threw soldiers into, watching them being torn apart and somehow thinking that the progress we made was enough. It was a terrible, dreadful conflict, the kind of thing we don’t tend to even glamourise (except when someone in Britain wants to do a Christmas sale, rather tastelessly), and generally, we see the generals in charge of it as ignorant, at least.

Monash, however, was a technologist. He firmly believed that there needed to be a change in mindset of the military, a change that did not take root until years later, in the second world War, thanks to another German general: Rommel. Specifically, Monash had this to say about the role of the Infantry in the military.

the true role of infantry was not to expend itself upon heroic physical effort, not to wither away under merciless machine-gun fire, not to impale itself on hostile bayonets, nor to tear itself to pieces in hostile entanglements—(I am thinking of Pozières and Stormy Trench and Bullecourt, and other bloody fields)—but on the contrary, to advance under the maximum possible protection of the maximum possible array of mechanical resources,

Monash was hailed by other generals for this push, though they didn’t seem to listen to him very much. Eventually, when he was given full command of Australia’s military, he instated policies that called for an advance in technology to diminish the risk and harm to people.

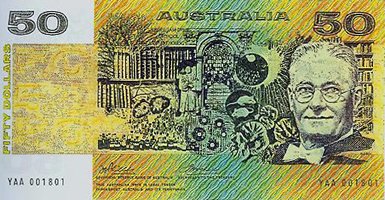

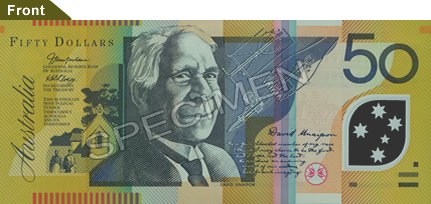

The Values of A Dollar – $50

We return to talk about the values expressed by who we, in Australia, present on our currency. I promise this entry didn’t take a lot of research. I’d normally joke that ‘I don’t recognise these bills’ because I’m a digital person and don’t make this kind of cash transaction very often. The previous denominations of currency are here (five, ten, twenty), if you’d like to see them.

Howard Florey

Chances are you know the name Florey, at least vaguely. You want a few moments…?

Chances are you know the name Florey, at least vaguely. You want a few moments…?

I can wait.

Tick tick tick.

What if I mention Sir Alexander Fleming?

Right. Howard Florey was one of the two people who shared the Nobel Prize with Fleming for Medicine. They discovered between them this stuff called penicillin, which helped spread antibiotics throughout European culture, and therefore, its economic and physical colonies. Florey was an Australian from Adelaide who conducted the first medical trials of penicillin – trials in which the patient died because Florey and his team failed to make quite enough of the drug.

Sir Ian Clunies Ross

Hobby horse time! In Australia, we have this thing called the CSIRO, the Commonwealth Science and Industrial Research Organisation. While a bit of a kickball politically, CSIRO has been a longstanding part of Australia’s push to scientific discovery and research, and has made crops, space-ship equipment, internet technologies and all sorts of neat things in that same sprawling general category of ‘what good can this thing be?’

Hobby horse time! In Australia, we have this thing called the CSIRO, the Commonwealth Science and Industrial Research Organisation. While a bit of a kickball politically, CSIRO has been a longstanding part of Australia’s push to scientific discovery and research, and has made crops, space-ship equipment, internet technologies and all sorts of neat things in that same sprawling general category of ‘what good can this thing be?’

CSIRO went on to create the system of wireless TCP/IP transmission that you now know as Wi-Fi, and the patent was used without credit for quite some time by businesses like McDonalds. We sued over that.

Anyway, CSIRO is cool, and Sir Ian Clunies Ross was at first a parasite researcher for its forebear, then eventually, its director. He was also a vet, which means that this was one of the first-printing notes to have two qualified scientists on it.

Edith Cowan

In the new printing, we have Edith Cowan, who was the first woman elected to Australian parliament. In uh, 1921? Which is not bad, considering that we didn’t have a Parliament until 1900 and all, but it’s still a wee bit embarassing since despite allowing women to vote, we needed to pass special laws to let them be elected.

In the new printing, we have Edith Cowan, who was the first woman elected to Australian parliament. In uh, 1921? Which is not bad, considering that we didn’t have a Parliament until 1900 and all, but it’s still a wee bit embarassing since despite allowing women to vote, we needed to pass special laws to let them be elected.

Edith Cowan was a pro-education, pro-information legislator. In an ironic twist, in her first election, she beat the man who was responsible for passing the legislation that gave her the right – or rather, stopped withholding the right – for her to run for parliament. Once she was elected, she pushed hard for womens’ rights and for education.

The most interesting thing about Edith Cowan’s very interesting life didn’t happen until after she died. Two years after her death, a clock was erected in honour of her – and people fucking protested it. What the hell, people of Western Australia? What possible reason to you have to not want to commemorate the passing of a person who did a thing first?

…claimed that monuments were inherently masculine and therefore not an appropriate form of memorial to a woman…

Oh, fuck you.

Now, Edith Cowan has a monument that gets handed around every day, her image is printed out and shared and given and everyone in the country possibly sees her about once a week. And to everyone who wanted to push back against her can suck a duck.

David Unaipon

Ho boy.

So before we go any further on the specifics of Mr Unaipon, it’s worth noting that David Unaipon was an Aboriginal Australian. To be specific, he was a Warrawaldie Lakalinyeri of the Ngarrindjeri, which is a set of words I am not only unqualified to pronounce, but are older than everything that I consider ‘my culture.’ Specifically, the term ‘Ngarrindjeri’ is a term used for a coalition of Aboriginal people in the area we now call Adelaide, and means ‘The People Of This Land.’

sigh

I’m sorry. I’m really so sorry.

Mr Unaipon is credited broadly as ‘breaking stereotypes of Aboriginal people,’ which can be rephrased as ‘made it harder for White Australians to be quite so blatantly racist.’ David Unaipon was a smart man, and we know that because he filed for nineteen different patents of working inventions. We can also, if we didn’t know it, infer that he was an Aboriginal man, because he couldn’t afford to file those patents fully, given that he was poor, despite having a job as a bookkeeper. There are all these lovely quotes about how clever Mr Unaipon was, but they all use such patronising language to do it.

Setting aside what Mr Unaipon was talked about, and how he broke stereotypes, let’s just look at what he actually did. He was an avid reader, loved studying philosophy, science, music and literature. He invented a technique for, uh, and I’m just going to quote the patent here, ‘converted curvilineal motion into the straight line movement,’ which is used in modern shears. It’s used in almost all modern shears.

Mr Unaipon was credited for this patent once. He received no financial renumeration.

He also wrote poetry and books. He was a recognised expert on ballistics. He also wrote about the synthesis of Christendom and Aboriginal beliefs that he held. He gave lectures, pushed for Aboriginal rights, and when he was travelling around giving these lectures we didn’t let him stay in most of the nice hotels because good christ.

Jesus christ this is a depressing bill.

Basically, we have here a pair of people who at some points in our history, we said we didn’t want. Now they are icons of our nation, shared and recognised by the people of our country… but probably not as much, or as well as we should.

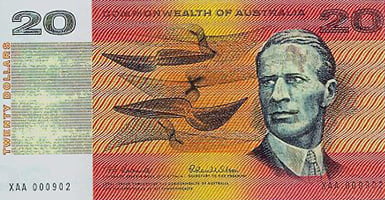

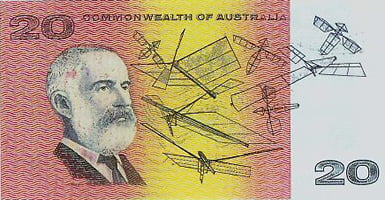

The Values of a Dollar – $20

Following on from our discussion of the $10 and $5 notes in Australian currency, we move on to the $20. We’re going to do things a little backwards this time: We’re going to start with the newer note. It’ll probably become more obvious when we’re done why.

Mary Reibey

I feel a bit bad that we jump so quickly to this. Ms Reibey was a businesswoman. Like, that’s basically her big achievement, the reason she’s remembered, because she was a woman who became very successful in business. And I mean very successful in business – her estate was valued at £20,000 back when there weren’t many £s at all. If you walk along the dock areas of Sydney (that’s all of them) you’ll find a number of old copper plates on the buildings signifying when they were made – and a startling number of huge-ass warehouses for shipping were made in the 1820s.

See, Mary Reibey (and if I spell her name differently from time to time, don’t worry so did she) was in Australia because John Burrows was arrested for stealing a horse. That is to say, Mary Reibey’s crime-committing alter-ego got arrested and deported to Australia. Why did she steal a horse? Because she was bored. After being deported, she took up work as a nursemaid, then married an East India company worker – and when he travelled, she managed his estate. And his family – which wound up at seven or eight kids (give or take).

And then her husband died.

Most folk figured this would be when the Reibey business holdings in shipping would be distributed. Were they hell. She consolidated, and expanded, and expanded so aggressively that she founded a bank in her living room.

She retired in 1828 and spent her later years kicking around Newtown and giggling at the fictionalised novels people had written about her.

Reverend John Flynn

Remember how I mentioned airplanes were important to Australia? Well, turns out if you live out on the stockyards that are each individually larger than Delaware, you don’t have a lot of easily access to doctors. That was, at least, until the Flying Doctors service was started – and it was started by John Flynn.

Flynn was a really nice person, and I don’t mean that sarcastically; he wrote books on how to survive in bush environments and deal with medical problems or foraging for food and he made sure the book was distributed for free in the outback regions of Australia. But knowing that wasn’t enough, he moved on to found the Flying Doctors – which is exactly what it sounds like. Small planes that could reach a spread of territory the size of countries were loaded with a pilot, a doctor, and then flew around stockyards all across the great brown land of Australia, checking up on people.

The Flying Doctors became a really easily ridiculed TV series full of turgid melodrama, because we’re not very good at making TV, which is a goddamn shame because they’re really quite cool and badass and they help people. But oh well.

Sir Charles Kingsford Smith

The first $20 was an interesting one because the two figures were linked in a way other notes weren’t: They were both aviators. Now, look, Australia is a country that’s basically the size of America with almost every major population center literally thousands of kilometers away from one another, so flight was important to our early, pre-internet infrastructure.

The first $20 was an interesting one because the two figures were linked in a way other notes weren’t: They were both aviators. Now, look, Australia is a country that’s basically the size of America with almost every major population center literally thousands of kilometers away from one another, so flight was important to our early, pre-internet infrastructure.

What’d he do? Smithy, as he was known, was kind of an endurance flier. First and lesser, he crossed the nation in a plane, which when the plane was basically a shoebox with wings and a bike engine, was pretty badass. Then he flew to New Zealand, crossing the Tasman. That was also pretty amazing. And then, he crossed the freaking Pacific.

The PACIFIC OCEAN.

When planes were a new piece of tech, we had to find out what they could do. We had to prove their limits. And Smithy was a grown man who was willing to strap his butt to one of these little pieces of wood and canvas, and risk his life in literally the most remote parts of the planet.

Sir Charles Kingsford-Smith died in a flight between India and Singapore, pushing the limits of what planes could do.

Lawrence Hargraves

Now here’s the odd one.

Lawrence Hargraves is a slightly strange one to talk about for me because there’s the stories the history books offer, which are interesting and kind of distant. And then there’s the stories my family swap about the guy, stories we have heard from his great-niece.

Who is my grandmother.

So what I can tell you that seems to be publically agreed upon is that Lawrence Hargraves was a geek, one of those multi-disciplinary geeks back before science was quite so easily distributed. Thanks to living on a coastline hemmed in by a mountainside, he had the option of taking to very high altitudes to fly kites, which he did, and, with that thrill undertaken, he then decided to try flying kites with him in them.

Astoundingly, Lawrence Hargraves did not die by doing this.

Lawrence Hargraves was fascinated by the idea of human flight, but he was also scrupulous about recording details. Recognise this man existed before the photograph was widely distributed. If he wanted to take notes on the design of a device he had to break out protractors and measuring tape, and he did. So thorough were his notes that his experiments were easily reproduced, multiple times, by other scientists. We know this about his notes because he refused to seal them. He never applied for a patent, he never tried to close his work off to others and when he passed away he made sure the work was public because he believed ‘science belongs to science.’

I guess the thing that most sticks out to me is this quote:

“Workers must root out the idea [that] by keeping the results of their labors to themselves[,] a fortune will be assured to them. Patent fees are much wasted money. The flying machine of the future will not be born fully fledged and capable of a flight for 1000 miles or so. Like everything else it must be evolved gradually. The first difficulty is to get a thing that will fly at all. When this is made, a full description should be published as an aid to others. Excellence of design and workmanship will always defy competition.”

Hargraves described scientific discovery as work, and he advocated cooperation vs competition to overcome great, almost impossible challenges. In an environment of hypercompetitive markets defined by flying machines, these words from a man who is in no small part responsible for flying machines happening at all should be taken more seriously.

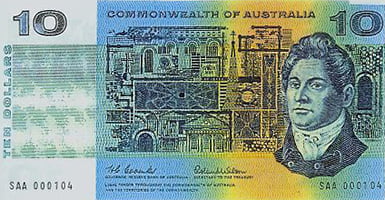

The Values of A Dollar – $10

Almost two years ago now, I started what I had at the time intended to be a set of posts about the people who appear on the Australian currency. That post, The Value of a Dollar established my theory that currency is the common art created by a government, and reflects values that government has. We’ve done the five dollar bill, so let’s talk about the ten dollar bill!

Francis Greenway

Francis Greenway was a convict sent to Australia for the crime of forgery. Take a moment to let that sink in – for a time, we had a man who was responsible for faking money, on our money. I’m sure he’d have been quite confused by the experience.

Francis Greenway was a convict sent to Australia for the crime of forgery. Take a moment to let that sink in – for a time, we had a man who was responsible for faking money, on our money. I’m sure he’d have been quite confused by the experience.

That’s not why we put him there, though. Francis Greenway was an architect, and was responsible for the architectural style of many key Sydney buildings. If you’ve ever been to Sydney, you’ll notice the older buildings have a very stocky style, with clear, brightly coloured white or red sandstone outside. That was Francis Greenway’s style. Essentially, Francis Greenway was responsible for the face of Sydney.

Henry Lawson

Henry Lawson was a short story writer, a poet, and a journalist when he had the time. Amongst his works was The Loaded Dog, a charming story we tell to children about a good-natured dog so stupid it eats dynamite and dies a horrific explosive death. I feel a bit bad here because Henry Lawson, while a crucial figure in Australian poetic history was overshadowed by…

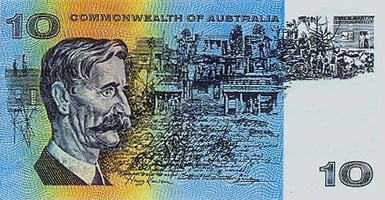

Banjo Patterson

This guy, the new ten dollar bills’ chisel-featured Banjo Patterson. Patterson was… well, a journalist, a poet, and a short story author, and in his list of work we have things like The Man From Snowy River, or Clancy of the Overflow, or We’re All Australians Now, or, oh wait, here’s one you’d have heard of, Waltzing Matilda.

This guy, the new ten dollar bills’ chisel-featured Banjo Patterson. Patterson was… well, a journalist, a poet, and a short story author, and in his list of work we have things like The Man From Snowy River, or Clancy of the Overflow, or We’re All Australians Now, or, oh wait, here’s one you’d have heard of, Waltzing Matilda.

Banjo Patterson and Henry Lawson once had a slow-release rap battle, on the newspapers.

But poetry continues onto the obverse of the $10 with…

Dame Mary Gilmore

There’s just alway something ironic on a tenner in Australia, it seems. The first ten dollar bill had a forger, and this ten dollar bill has a socialist on it.

There’s just alway something ironic on a tenner in Australia, it seems. The first ten dollar bill had a forger, and this ten dollar bill has a socialist on it.

Dame Mary Gilmore was a journalist, poet, and political activist. She was also, as I say, a registered socialist – a firm believer in a structure where the primary purpose of the Australian nation was to benefit Australians – and therefore, she fought for and argued for ‘extreme’ positions in the 1920s like ‘Equal Pay For Women’ and ‘Government Subsidies For Mothers Who Want To Work’ or ‘Give Disabled/Disadvantaged People Money To Live.’

She had to separate from her political party for being ‘too extreme.’

Then, Mary Gilmore went on to write poetry and letters for the Tribune, which was the communist party’s newspaper. And then, because her poems kicked ass, she was made a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire by the crown – and she was the first person to be awarded that status thanks to literary work! Then she went on to write patriotic bolstering poetry, believing it important to give people strength to work together during the time of war, particularly No Foe Shall Gather our Harvest – the poem that is included on this note.

I like this. I like that our second most commonly-used currency used to have a forger who made a city pretty, and now it has a poet who opposed the idea of money.

Dame Mary Gilmore’s ideals have not yet been met, and we should not forget them.

The Values of A Dollar – $5

Currency is the art of a nation’s soul. When you look at a country’s money, you can see things about what that country values and respects, things that both represent that country, and things that represent that country’s place in history – and what about its history it deems important enough to immortalise, fold up, and stuff into someone’s butt pocket. The things a person has done for the country earn them that place. I’d like to talk some about the nature of Australian money for a little bit, as the topic, I feel, reflects well on us as a country, and lords knows I don’t mind making people feel that my country is awesome. Money is also popular, so let’s see what kind of story we can find in the tale of Australian money?