3e: Objection to Formula

When I started on this article, the plan was to talk to you about the magic item system in D&D 3rd edition, and let’s put a pin in the word ‘system’ there. But engaging with it meant looking at a place in history and a realisation of how I’m not just talking about stuff from an earlier edition of D&D I’m talking to you about an earlier version of myself.

As long as there has been an online, it seems, I have wanted to make things and put them on there.

Continue Reading →3e: Sticks and Stones

Alright I’m up late and the thing I was working on didn’t work and I don’t want to fall behind on my schedule so let’s just belt out something about the ongoing grievance I have in how 3rd edition D&D treated spellcasters as a better class of people with their own higher standard of living because being able to rewrite reality at will is by no means a perk enough to justify not feeling bummed out.

Let me talk to you about sticks and stones powers.

Continue Reading →3e: The Love Potion

We’re all kind of on the page that ‘love potions’ in stories are probably bad, right?

Those things that you could buy in 3e as a cheap, disposable magical item?

Continue Reading →3e: Monk Attacks

Have you ever encountered something where a system is evident but the language for discussing it isn’t?

Cast your mind back to the days of Dungeons & Dragons 3rd edition. No, not 3.5, the one that forms the basis for Pathfinder that people generally claim is ‘the good one’ before 4th edition (the best edition) came along. 3rd edition, the edition before 3.5, which is what it definitely was, was notable for being ‘the things people like about 3.5 D&D, but all quite a bit more shit.’

Know what was really bad in 3rd edition? Well, a lot of things, including Paladins, Rangers, Fighters, Barbarians, Bards, Half-Orcs, Half-Elves, Halflings and all but two melee weapons, but, in particular for this conversation, one class that was quite bad was the monk.

Continue Reading →3e: Prestige Fantasy

In 3rd edition D&D, you started with a class. Then, in the DMG, they introduce the idea that as you level up, you could get access to a ‘prestige’ class, this idea of a special kind of class that let you create a different, interesting permutation of the base class. Based on the prestige classes in the DMG, it was pretty easy to see that these were meant to be interesting forks for the way a character’s life could change, as a way to ‘pick up’ a class in the middle of a game that didn’t lock you into starting something from scratch.

This interesting idea quickly fell by the wayside as instead of alternative classes you could introduce into the game in a later space that players could graduate into when their story became specific, prestige classes became the natural progression a whole bunch of players expected to graduate into, and they were the main reason to buy new splatbooks.

The problem, of course, is capitalism, but let’s look at the problem anyway.

Continue Reading →3E: Evil Gods And Ridiculous Rules

Bhaal. Cyric. Gruumsh. Shar. Myrkul. Malar. Talos. Lolth. Bane. Tiamat. The names of dreadful forces, towering gods of evil and spite, entities that draw power from the very nature of what it is they embody. These are the evil deities of the Forgotten Realms, whose machinations and operators sprawl across the world before you, and whose presence makes the world a diabolical and dangerous place. They are powerful, they are malicious, they are intelligent, they are gods and above all, uniting them all, they are evil.

These entities, by the rules for gods in worldbuilding laid out in 3e, don’t make any fucking sense.

Continue Reading →3e: Otyugh Signalling

There’s this type of monster, called an Otyugh.

The monster manual in 3rd edition describes them thus:

This creature looks like a bloated ovoid covered with a rocklike skin. A vinelike stalk about two feet long rises from the top of the disgusting body and bears the two eyes. Its mouth, little more than a wide gash filled with razor-sharp teeth – is in the center of the mass. The creature shuffles about on three thick, sturdy legs and has two long tentacles covered in rough, thorny, protusions. The tentacles end in leaflike appendages covered in more thorny growths.

Monster Manual, Page 204

Now, what does an Otyugh mean?

Continue Reading →3e: The Excellence of the D&D Onramp

There’s a recurrent pattern of discourse in the TTRPG community, especially amongst indies, that, cooked down into its parodically simple position, goes:

D&D is hard to teach, and nobody plays it properly.

So let’s talk about D&D having one of the absolute best onramps of all time starting with when I started to play it, in 3rd edition D&D. I bring up this edition of the game because it is absolutely a pigs arse of a game, and I know that a lot of the systems of the rules are only attempted by extremely bold people who needed something systematised.

Lemme tell ya, you run one aerial combat in 3rd edition you quickly invest in every technique you can to ensure you don’t have to run another.

Continue Reading →3e: Your Guild Leaders Are All Trans

3rd edition D&D doesn’t do much with queerness. It’s an interesting artifact of the late 90s, early 00s, where the whole edition was something that, to use the parlance of now, would be claimed as ‘woke propaganda’ now, was still something that didn’t feature a queer NPC until a Dragon Magazine published well into the release schedule of 3.5, and when it did, he drew heat that the editorial lineup of that magazine had to fight about it in the letters column of the next issue.

There are other areas that the game can be seen as surfacing queerness, and I’ve talked about one – the way that the D20-SRD component Unearthed Arcana introduces transphobia in the form of gender dysphoria as a byproduct of literal madness. That’s not great. It is, in fact, uh, bad. You can even have a multiple personality disorder identity which has a different gender to you, isn’t that cute?

But uh, okay, so that’s one way that explicitly not-cis-not-heteronormative culture showed up in 3rd edition. Uh… is there anything better? Anything that could be considered, um, nice?

Continue Reading →3e: Finally Talking About Grappling

Alright, sure, let’s finally tear off this bandaid.

When I bring up the rules for 3e D&D, there are some rules I bring up that the rules were bad at, to, you know, bully them. The challenge rating system was pants, for example, and I will never not mention that. There’s also the imbalance of the wizard, the numerous busted prestige classes, all of that stuff — it doesn’t work, it’s build on bad assumptions, it relies on players to create their own balance matrix. Lots of great fun reasons to make fun of things.

One area of the rules I make fun of a lot is the grapple rules.

Continue Reading →3e: The Epic Level Handbook’s Monsters

I’ve spoken about the Epic Level Handbook in the past, as a sort of ‘pull the corpse open and look at its insides,’ sort of way. Y’know, look, here’s where the liver is all weird and this bone connects to that bone and now you can see how all these parts in a broad way relate to one another and also why the patient is stone dead. It’s a good article, I recommend you read it because it’s about big, overarching problems the book had. I also have written about the problems of challenge ratings, the black box of imbalance that 3rd edition D&D has going on, a black box that gets worse and worse over time, all building on the impossible fundamental error of D&D 3e’s design philosophy, in that it’s intentional for players to be able to be bad at it.

But I didn’t come here to talk about that.

That’s not why I busted out the Epic Level Handbook, to drag the ugliest system rolled with worst dice through the streets again. Nor is to delve into the misshapen balance parameters presented by treating a single level of a class as equal across all classes when representing characters built well and characters built badly. A level 21 fighter is meant to be an equal challenge for a party to a level 21 wizard, even though one of those is essentially a tough guy with a sword and the other is a tough guy with a sword and the power to stop time.

Instead, I want to talk about the monsters of the Epic Level Handbook.

Because I think a bunch of them are cool, even if their execution is stupid.

Continue Reading →3e: Arcane vs Divine

What’s the difference between Arcane magic and Divine magic?

Familiar as I am with 3rd edition, I know there’s definitely a structure that says Arcane magic is the slightly more powerful one, and that Divine magic is easier and more convenient to use out of the box, but that’s the perspective from one extremely bleeding edge level of power that I never really got to play with. My experience of wizards and clerics in 3rd edition were always characters who did that and something else, in order to keep their power level meaningfully contained. Basically, I liked a wizard with a sword or a cleric with a pet rather than just taking my Busted Spellcaster Classes straight.

Until 4th edition approached and rebuilt every power source with a specific holistic vision for the shared traits of powers, Arcane magic and Divine magic existed as parts of a continuum that shaped your vision of the world at large. And the machinery of the game was designed to get people involved at one point and you were meant to grow as a player while you did.

What, then, was the difference?

Continue Reading →3e: The Beauhort

Back in 3rd edition Dungeons And Dragons there were a lot of problems in character building, but I dedicate special attention to those that pushed players making reasonable, desireable choices into things that made the game strain. It was super easy to make an overpowered cleric or druid if you just looked at what they could do. It was easy to snap the game in half with the Spelldancer, just doing what the class suggested you do. It was easy to buy into a class fantasy that stranded you unable to confront the challenges the game had.

And if you wanted to pick up a boyfriend in-game, there was an obvious and available way that kinda made the game buckle a bit — just take the feat Leadership.

Continue Reading →3e: Haste!

Oh boy you know what’s the most broken spell available in 3rd edition D&D well now you mention it it’s a contentious slot because there are a lot of spells that are really, really broken and third edition had a lot of them flying around but when it got broken you kind of had to start in the core rulebook and see the things that you’d wind up seeing used all the time and nothing was really ever going to wind up being as broken as this one it’s haste it’s haste look it’s obvious I’m talking about haste haste was so very goddamn broken in third edition D&D.

3.5: The Supermount!

Hey, do you wanna be agile, hostile, and mobile in 3.5 and play a character whose primary and major ability is engaging in melee combat and not casting spells?

Let’s talk about the Supermount!

Continue Reading →3.5 D&D: Drinking Souls

The Book of Vile Darkness is not a book for players. On the fourth page, it lists Hide This Book!, which states that the book should be treated as if it were a published adventure, that it should inform and add to player experience, but never be treated like other player option books.

Let’s ignore this and talk about the Soul Eater, a prestige class that requires you to be Evil and which is contained only in the Book of Vile Darkness.

Continue Reading →3.5: The Archivist

Hey kid, wanna read some dirty books?

D&D is a game of nerds, and therefore there is always some degree to which it will reflect the vision of the kinds of nerds that made it. By default, there is an idea of power that lends itself towards the obvious, with mighty barbarians and fighty fighters plunging onwards into the fray, but it almost seems too obvious that a game that for thirty years was seen as the domain of the kind of dorks who boasted about their test scores just so happened to land the majority of the powerhouse play options in the lap of the characters visually represented by being physically unathletic and carrying a big book everywhere.

In a game full of busted stuff, it’s well known that in D&D 3.5 the most busted stuff comes from the host known as the ‘full spellcasters’ – characters whose power derives directly from their spellcasting as the primary thing they do, and who get nine levels of casting spread out over seventeen levels, eighteen if you suck and pick a sorcerer. And amongst those, the typical top tier are the Wizard, the Cleric, and the Druid.

The Archivist is the rare example of a character class presented in the 3.5 D&D expansions books that manages to not just exist alongside those three, but in a way, exceed them.

Continue Reading →3.5: Use Magic Device

The most comically, hilariously, overpowered skill in 3.5 D&D was a skill that very few classes got, could only be used trained, couldn’t be used reliably and had a drawback if you ever rolled a natural 1. It was also something that wizards didn’t tend to care about having, clerics could almost never take advantage of, and if you had access to it, would take over your build because of what it let you do.

It had a stupid name too.

It was Use Magic Device.

Continue Reading →3.5: The Misfit Children Of The Complete Books

Dungeons & Dragons is a beast of structures. One of those structures is a class, which gives you a collection of mechanical abilities to express how you operate in the world. One of the other structures is a book release schedule, which gives you a sequence of products that Wizards would be very happy to sell you, and would make your game better, no really, check it out, this will totally address problems you’ve mentioned and noticed. Back in 3.5, the first wave of these was the Complete books, the Complete Warrior, Complete Adventurer, Complete Arcane and Complete Divine, which I will note, did not in fact, complete those options. Blatant false advertising in my imho.

Each of these books had three classes in them, meaning that after the initial release of the Player’s Handbook, we were presented within the first six months with twelve more classes to select from, which makes sense. Binches love classes. I have a long-standing opinion that every Complete book that presents new classes presents one legitimately interesting class and at least one complete turkey. What you almost never got was a powerful class out of a Complete book.

Of these classes, I actually think I have to revise my assessment. Like, some books didn’t really have an option that managed to reach the high water mark of fine.

But that’s a list! We can look at a list!

Presented then, in an itemised list, are the twelve classes of the Complete Books, 3.5 edition’s misbegotten I Guess player options. We’re going to look at the worst book to the best book, in terms of whether or not the classes are powerful. This is non-scientific and you’re reading along because I’m charming, so don’t get too het up about it.

Continue Reading →3.5: Sex Is Bad

The Satanic Panic did things to the culture. We can pretend it wasn’t really a thing (because it was a thing about a thing that wasn’t a thing), but undeniably, a bunch of angry parent-types bellowing about the way their kids were being exploited until the exploitation changed colour did pervert the course of business interests. It was largely, just not worth the fuss to do things that could annoy that vocal body, and you could just change the decals on some of the stuff you did. I mean, having a bunch of weird outsider kids who liked playing D&D doing things like ‘being friends’ could be super upsetting for the parents of those kids, especially if those kids were having fun with their friends and not wanting to have fun with their family. Maybe the family sucked? Anyway, point is, that the Satanic Panic had a direct and meaningful impact on the big business juggernaut that was Wizards of the Coast. Famously, they stopped using demonic imagery on Magic: The Gathering for seven years.

Was that why 3rd edition Dungeons & Dragons and its followup edition 3.5 thought sex was bad?

Nah probably not, this was probably just further building on the game’s pre-existing protestant ideology that thought Sex Was Bad. Let’s talk about the Ace Rights prestige class.

Content Warning: Acephobia! And uh… amazingly, just general talk about sexual assault? THIS WAS SUPPOSED TO BE A FUN ONE.

Continue Reading →3.5: The Adherent

The 3.5 D&D Paladin has problems. It may be one of the better melee classes in the book out of the box but that doesn’t mean a hell of a lot and there are a number of levels where the Paladin just increases a few numbers and nothing else changes for them. These are known as ‘dead levels,’ and honestly, in 3rd edition D&D, for the melee characters, you could do worse than that. A couple of classes got worse when they levelled up.

I therefore tried to solve this problem in the fashion that to me looked the most sensible, straightforward, and functional way. That is, I decided to make a single class that addressed the Paladin’s balance problems, integrated Domains as a design element, and let players play a whle bunch of different characters that were only united by being primarily combatants and empowered by something beyond the self.

I made the Adherent.

3.5: Fighting Backwards

Dungeons & Dragons 3rd edition was an interesting system with a lot of good ideas. In a big, top-level mechanistic way, it had some good ideas, like making standardised rules for how categories of things worked. Some abilities were spells, some were spell-like abilities, some were supernatural, some were extraordinary, and if it didn’t fit that category, it was generally unique, but by making these categories meaningful there were a lot of rules that just got tidied up. Things were complicated, and the rules system wanted to cover very complicated things. 2ed had some very complex monster abilities, and 3ed wanted to be able to run things that looked a lot like them. Not quite compatibility, but certainly to carry some of that same ‘oh, this can fight like this OR it can be a spellcaster OR it can teleport at will,’ kind of design.

Thing is, this kind of top-down design idea was done as a half measure, and also didn’t preclude the system from bringing in some real problems of its own, like the way that all the melee classes were garbage and the wizard and druid were overpowered. There had to be a big balance enema, and that enema was called 3.5. It was an opportunity to get you to buy all the books again, but also a chance to do some really comprehensive, holistic errata, onboard new players with the better rules. This could address those balance problems, too, by reigning in the wizard and druid and maybe the cleric as well, and then giving a good shot of power to those weakest classes, Everyone Else.

How’d that work out?

Uh.

Well, the Druid got Natural Spell in the core books, so it became even more powerful. The cleric didn’t get the slightest bit of reigning in. Wizards lost one of the most powerful spells they had and were still otherwise completely as busted as before. The bard, ranger, barbarian and Paladin all received improvements that didn’t really address the categorical problem of how they worked, but certainly made them less boring. What about the fighter…?

Well, and this is going to sound unbelievable, they made the fighter worse.

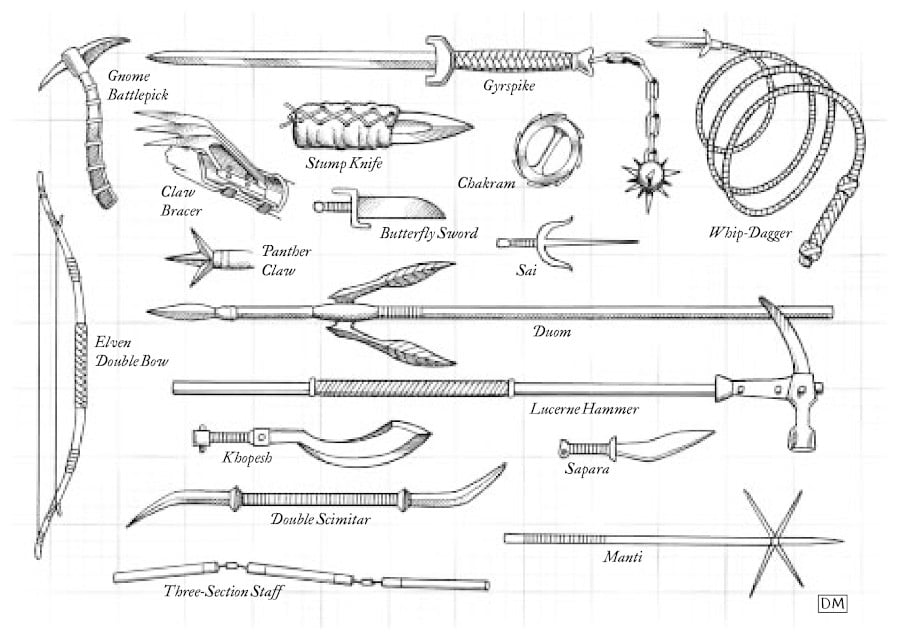

Continue Reading →3e: ‘The Exotic’ Weapon

Dungeons & Dragons is a game about creating a shared, temporary, fictional, consensus reality with your friends and ceding authority to manage the apersonal elements of that reality with one of your friends who can be trusted to use that trust in order to direct a narrative that provides satisfying engagement for the whole of the group, as I’ve always said. Part of that consensus reality is therefore the idea of managing what is and what constitutes normal, which is, overwhelmingly often, done with literal no rules or insight into how reality functions on an intrinsic level. You do not need rules for gravity (check flying rules, p56), you do not need rules for what dying means (check the head-in-a-bucket rager, p114), you do not need rules for why a culture wants a rightful king in power (check bend-at-the-knee p1312). The fictional reality does not have a different set of mathematic rules underpinning their reality (though you can make a case that that’s what a D20 is if you’re very meta and boring), light and vision do not behave differently, planets whirl and matter can be touched.

Rather, the reality of D&D is a collection of signifiers of the very small set of differences between our reality and theirs, and that is, in part, established with rules that recognise the conventional vision of what is or is not normal, most often represented by the tools that are of interest to adventurer player characters. It is in this regard that the weapon proficiency system tells you what is normal and what is other.

Continue Reading →3e: Knowing What Love Is

Back in 3rd edition D&D part of the worldbuilding was done through Gods. Rather than give every single god a particular unique mechanic as was the trend in second edition (the rarely-spoken-of-on-this-blog 2e, for fear Lorraine Williams will sue me, on the internet), this was handled by creating a set of tools available for every god,and that god gave you a handful of them.

Continue Reading →3e: Challenge Ratings Are Hot Garbage

Sometimes an article is just a big tweet, and this is one of them. In this case, the bigness of the big tweet is however, beyond the boundaries of a mere tweet, so let’s go. The 3rd edition Challenge Rating system, which was replaced in 4th edition by the XP budget of each encounter, was hot garbage and nostalgia for it is at best rose-tinted glasses, and at worst a signal of complete mechanical illiteracy.

Let’s talk about the 3rd edition system for creating* balanced** combat*** encounters****, the Challenge Rating system.

* Sort of.

** Sort of.

*** Sometimes.

**** Sort of?

The best of 2021, Part 1 – D&D

I wrote some bangers last year.

I sat down at first to give a sort of top ten articles of my own last year, that weren’t covered by specifically the header of How To Be, Game Pile or Story Pile. I tried it, and found that I had run out of slots for ‘absolute banger of an article’ in two months of summarising posts. Then I realised there were whole trends of things to write about and then I realised, hell, this is my blog, you’re here for my content, and unless you’re Vincent or Tab or Kate (hi, you three), odds are good you miss an article or three I write.

We’re going to do three of these this week. A whole bunch of bangers, divided up by the type of writing it is, and why I might want you to go reread it. First we’re going to talk about general content – stuff that I think you should link to other people outside the blog, posts that explain some complex concept in a way I’m proud, but also which doesn’t necessarily fit the other stuff.

And so here, I’m just going to bring your attention to a big pile of things I’d already written that are really good and which I know have escaped your attention, yes you, and today, it’s going to be about the Dungeons & Dragons, DMing and Worldbuilding articles.

3.5 Memories: Worse Than The Fighter

In Dungeons & Dragons 3.5th Edition, a thing that’s not at all un-awkward to say, there was a set of hardbound expansion books released as a group to satisfy groupings of characters as an archetype. The first set of these, released around 2003, were The Complete Divine, The Complete Arcane and The Complete Warrior, a trio of books that kind of told you what they were about in the name. You had arcane spellcasters, divine spellcasters, and uh, everyone else, I guess.

The Complete Warrior had to bear up as the space for all the classes that weren’t divine spellcasters (but the ranger and paladin can play here too, sure) and all the characters who weren’t arcane spellcasters (but there’s stuff in here for melee spellcasters). Barbarians and Rogues and Monks all got to cram in on this book, but based on the name and the style, and of course, the preponderance of feats in this book, this is the book that’s for fighters.

It’s also a pretty cool book, if you’re looking at the good stuff in it that you want to use and make sure people can use. LIke this book has tactical feats, a category of feat that kind of roll together a small number of ‘not enough for a full feat’ advantages into a single grouping, and that’s a really good way to expand expertise on fighters. Prestige classes in this book include the Actually Good Frenzied Berserker, the kinda decent Tattooed Monk, the sorta-maybe-why-not War Chanter, the busted as hell Warshaper and that’s four classes worth having access to in most campaigns. The excellent Combat Brute tactical feat is in here, and uh

Anyway, the point is this book is one of the books I think of pretty positively.

It’s also a book that features the rare examples of a class actively worse than the Fighter.

The ‘Samurai.’

3.5 Memories: The Necropolitan (That Fucks)

Ever type out the title of an article, and look at it and go: Well, I can’t change that now.

3e D&D: SONIC FIREBALLS

In the pantheon of D&D spells, there’s nothing, it seems, more iconically important to the identity of the game than ‘fireball,’ a spell that apparently nobody ever anywhere would come up with without D&D bringing it to their attention. Hm. Bit sarky there, I should come back at that again. Anyway, Fireball! What a great spell! A classic, a powerhouse, a spell that always comes quickly to the fingertips and that players love to hear when the wizard is about to start some shit with a fireball.

Anyway, you’d never bother casting it in 3rd edition D&D.

Continue Reading →3.0 D&D: Everyone Shapeshifts

Min-maxed 3.0 D&D was fucking weird.

I use the term 3.0 to talk about ‘third edition’ because there’s this weird way that people treat ‘3rd edition’ D&D as a single game, and not a period of time between the last release of 2nd edition and the first release of 4th edition. 3rd edition content is still being made and the game is still being played, even if I’d moved on from it. Important to this, though, is that ‘3rd edition’ is a term that I feel inappropriately ambiguates the two games made in 3rd edition.

When people are criticising 4th edition — hey maw he’s defending 4th edition gain — sometimes you get a ‘timeline’ argument; the idea that 4th edition, as a game that was only actively published and promoted for six years before the introduction of 5th edition. 5th edition has been going for 7 years since then (two of which were pandemic years), and 3rd edition went from 2000 to 2008, showing that 7 and 8 years are ‘good’ times for a game to exist, and 4th edition’s 6 years indicate that it was a ‘bad’ time. Thing is, 3rd edition D&D, the thing before 3.5, was only around for 3 years, and it was not the same game as 3.5. You couldn’t just pick up classes, creatures, or monsters and port them over. First party feats and classes were generally all weaker than 3.5, and spells were largely stronger.

4th edition never released a supplement that wasn’t compatible with all of 4th edition. By comparison, 3.0 lasted for 3 years, and 3.5 lasted for four – an immense rules patch apology.

And trust me, it was an immense rules patch.

Like, did you know in 3rd edition, in min-maxed groups, you basically never bothered building for physical stats if you were starting after level 3 or so?

Because in a min-maxed party, you very rarely were dealing with un-polymorphed characters.

Continue Reading →3.5 Memories: The Struggles Of The Hexblade

We’ve spoken before about how the wizard and sorcerer presented a sort of top-and-bottom of the top tier of D&D 3.5’s utterly unbalanced nonsense space, and it’s something of a storied matter of lore that the Fighter represents a most obvious terrible class. It creates a pretty simple narrative that spellcasters are great and melee damage dealers are ass. This isn’t totally right – after all, the Truenamer, the worst D&D class, period, is a spellcaster, and there are classes that are primarily melee damage dealers that aren’t underpowered compared to standard enemy content.

But it does hold, generally.

The core rules brought with it a set of three arcane casters and four divine spellcasters. Of those divine spellcasters, two were what we call ‘full’ spellcasters – they cast spells at level 1, and every level their spells get better – and were the Druid and the Cleric, two of the most stupidly powerful classes in the game. The other two were the Paladin and the Ranger, who had a pretty interesting structure; both were full-base attack bonus classes, with special abilities that made them better in melee combat, and after level 4, they started to get a small number of spells that gave them a lot of potential options. And honestly, the Ranger and Paladin were pretty damn good. They weren’t the worldshakers that the primary spellcasters could be, but if you wanted to hang in their parties, you were at least going to get interesting choices and could do some cool things.

But what if there was an arcane class that was templated off the Paladin and the Ranger?

What if there was a melee-capable class that got arcane magic and special powers to round out their flavour space?

Well, there was.

Presented in the Complete Warrior, we got our Arcane Paladin-Ranger-type.

It was the Hexblade.

And it suuucked.