3.5 Memories: The Transphobia Of Unearthed Arcana

Content Warning: Mental Health, Transphobia.

Let’s talk about effort.

Continue Reading →3.5 Memories: The Palingenesis Of Xen’Drik

Content warning: I can’t help myself from bringing up the Nazis.

I’m not joking.

3.5 Memories: The Complete Adventurer

Before I go on to bang about something big and complicated in this book, I want to note, up front, that this book has Wraithstrike, one of my favourite 3.5 D&D spells, and which introduced the idea of spellcasters spending spell slots for short-term, immediate impact in combat, something I love and which always thrilled me when I got to play with it. If I only got this book for that one category of spell, I’d be pretty okay with it.

Just some uncritical, unvarnished, un-preambled praise.

Going back through my old 3.5 books is sometimes an exercise in wondering, in hindsight, just what exactly justified the book’s cost. At the time I was actively playing 3.5 D&D, the books were purchaseable research tools, things to leaf through and read and cross-reference. It was like getting a complex box of lego, and you could share your creations with other people.

Most of these books, I look at the spines and I have a warm thought or two. It tends to be something like oh yeah, remember how this lets you do that or that. Most any given book has an absolute dogshit class, one really embarrassingly weak thing, and one really busted thing in it. There’s always some stuff that’s, you know, decent, or stuff that becomes decent when you know what you’re doing. Basically, these books were themselves, even if never used to build a character, fun to play with.

Sometimes you’d find a book that had in it something that resisted play. Something with an obvious allure to it, but something that was hard to see how to make it work. These were often a bit like Finger Traps, kind of like Rubiks Cubes – puzzles where the impracticality of solving them was the point. Character options that asked an interesting question.

For the Complete Adventurer, the question was the Fochlucan Lyrist.

3.5 Memories – The Smoochless Book Of Exalted Deeds

Back in D&D 3.5’s hey-day, which was, it seems to look at these printing dates, 2003, they were so convinced of their infinite expandability and the depth of their market that they made themselves a special label warning that this book was of the Mature Line of products. In the time of this line’s existence, as best I can tell, there were a total of two books Wizards of the Coast published on it, with the first being the perhaps obvious Book of Vile Darkness.

The most obvious joke, ‘vile dorkness,’ writes itself, and is 100% justified.

The other book in this line, though, is the Book of Exalted Deeds. This book got to be Mature because… of… reasons, most of which seemed to be to add a few dollars to its sticker price and, I suppose, to let it reference the Book of Vile Darkness, which it felt a need to do. Now, there’s a lot to be said about the difficulty of composing a book whose entire foyer has to be a treatise on how to not only ‘be good’ but also be really good in these proactive ways that translate to good game mechanics and engaging character beats for an ongoing story. You can really feel the front end of this book trying to park a bus in a bike spot, as it seeks to bring up things that are good things for a character to do, in a proactive and engaging way, while still buying into the slightly mangled moral framework of D&D as she is written.

Continue Reading →3.5 Memories – The Cleric Archer

It’s by no means a secret that 3.5 D&D’s balance was off in some ways that made ‘good’ and ‘best’ categories of things a little unintuitive, like how the best stealth-based character was a wizard, or the best speed-based character was the wizard, or the best big, strong melee character who smacked things with a sword was a wizard.

Hm.

If you ever got asked, houwever, about ‘best’ builds, there were always a handful of builds that stood apart because they had unique combination of effects. There was the Supermount, for example, or the Wildshape Ranger, builds that were renowned for having access to something that set them apart from things of their type. And, especially since Legolas was in the popular media at the time, there was often a question about how to make the best archer. There were plenty of archery feats, and it seemed for once, this was a challenge the fighter was perfectly suited to address – the excessive strength of the Barbarian’s rages wouldn’t necessarily apply, and sneak attack for a rogue was harder to get, so perhaps, perhaps, with a host of feats available, surely the best character to take them would finally be the Fighter?

Nope.

It was the cleric.

3.5 Memories: GAY RAINBOW SNAKE

Eff it, sometimes I need one that’s a walk.

The way these posts tend to happen is I go into the garage where my physical D&D books are kept and I reach into the shelf and pull out a book I haven’t read lately, flip it open and see if what I see on the page reminds me of anything and this month we got the Complete Divine and the page I flipped to was the Rainbow Servant.

Good news, this class can do some beautiful bullshit, and it can do it while looking really gay.

What we’re going to deal with her is a lovely overlap of unintended consequence. See, D&D creation was ultimately fractal; when you made a new class or a new race, you could test it against other stuff but as more stuff happened, you would always find combinations of stuff interacting in ways you maybe didn’t intend. Sometimes this meant you could find two different spells in different supplements did identical things, but one was much stronger, and sometimes this meant that a character could take two identical feats for double the effect. The copy editors at Wizards of the Coast could keep on top of this most of the time, but not always.

What mostly happened, then, was things were tested against a core of ‘what was in the player’s handbook’ and the more sources you added, the more wild things could get. That was one of the ways the game got weird, too – the more of the exciting and interesting stuff you started to include, the more weird byproducts you got.

This time around, what we have is the collision between the Complete Divine and The Miniatures Handbook and repeated in the Complete Arcane. The two parts at work here are the Warmage (a class) and the Rainbow Servant (a Prestige Class).

Rainbow Servants are spellcasters that learn from and benefit from a relationship with couatls, a type of sorta-kinda-Aztec-y divine monster creatures that are snakes, that relate to rainbows, and yet, suspiciously, aren’t shown in rainbows in their default art. Must seem gay. Anyway, these couatls grant special gifts to arcane spellcasters, and those casters get to be Rainbow Servants.

As written, the Rainbow Servant is a prestige class for arcane spellcasters that want to add a bit of divine vibe to what they’re doing, in exchange for eating some spellcasting levels. Most of the time, this tradeoff isn’t worth it: spellcasters that give up spellcasting levels need to get something truly immense in exchange. The stuff you get out of the Rainbow Servant is domains (which add spells to your potential repertoire), beautiful rainbow wings, and then, eventually, the entire cleric spell list added to your spell list.

For a sorcerer or wizard, this represents more options, but not more choices. These classes still have to spend resources to know those spells. Wizards adding the entire cleric spell list to their spellbook is a lot of power, but you had to give up four levels of spells to get there, and that’s typically not a worthwhile tradeoff. Sorcerers need to spend their very limited spells known to get those spells, but you already don’t have enough spells.

So, Rainbow Servant is a bit weak, and you might pick it up if you really really wanted the rainbow wings, for example, or you had a strong concept for a divine-arcane mixed up spellcasters.

But then, let’s introduce to the conversation the Warmage.

The Warmage is a class designed for a kind of different form of D&D. It was originally made to be a boomspell platform for the miniatures game, which used D&D combat rules to resolve a tactical miniatures wargame. Noticing that for fast combat, choosing spell preparation is a pain in the ass but choosing the right spell for the job on the spot is hard enough, they created a spellcaster who just always had access to all their spells, and made that spell list limited.

So.

If a warmage adds spells to their spell list – like with a domain – then suddenly, they can cast, spontaneously, every spell on the domain list that’s of a level they have access to. That’s pretty good. Then when they hit level 10, they have all the spells in the cleric list, available to cast spontaneously, and the existing warmage blast spells.

That’s really cool!

This build is also not especially strong, at least, not most of the time. You need to hit around level 16 before this happens, and at that point, you have a character who’s casting lots of different level 6 spells. You’ll never get access to 9th level spells (without some nonsense), but you’ll have enormous flexibility all the way up there – the best cleric spell for the job, all those lower level slots able to turn into useful buffs, and a bunch of handy special abilities to go with it.

Now.

This is clearly unintended consequence. The Rainbow Servant was not made to be a route to ‘late-game megacleric wizard.’ The Warmage was not created to turn into a support machine with the right level choices. These two elements were not created to interact with each other. One can argue that this interaction, being unintended, should be excluded. After all, if it wasn’t tested, it might have unforseen consequences. This is how a lot of MMOs behave: even things that are designed to replicate one another are often designed to not stack or interact, so as to prevent players from having too much of an effect. Check out how for a time, World of Warcraft had a standard list of ‘raid buffs’ (and may still have but I don’t care to check).

However, this is where TTRPGs have a freedom. You can look at how players engage with the game, and make those choices on the fly. You can decide if a player doing this stuff is eating up time. Hypothetically, you can even decide how in your game it’s okay for things to work out unfairly in one player’s favour, because that player may be less strategically minded, or not inclined to take advantage of the power, or bad at managing the information load. You might decide that it’s okay, because you can see other ways other things can be just as powerful that you are okay with. You can even decide to adjust this as the game goes on.

But don’t forget that sometimes, there are cool, odd interactions that some players may pick up just because they like the gay rainbow wings.

3.5 Memories: Okay, Fine, Let’s Talk About Zceryll

Back during August, I looked at the Tome of Magic, a 3.5 D&D book, which involved looking at the the Binder. The Binder was one of the classes presented in that book, where the basic idea was that the binder had these things, called Vestiges, that you could sort of cold-swap between to get different abilities based on your different needs; the task of swapping character mode was fast enough that you could do it between encounters, or on the far side of a dungeon door, or hurriedly while the guards are on their way, but it wasn’t something you could hot-plug in between combats. The Binder was a weak character class by default that could, with its variety of options, hot-swap into a form that was usually about as good as a rogue with most of the gear they want.

Note those italics.

When it comes to D&D content, Wizards put things in the books, but they also made a thing of web expansions – pdfs and website content that you could add to your game, stuff that came from the Official Source and was generally made to be safe enough to include in any game, and that is where we got the Vestige that on its own takes the Binder from ‘incredibly fair, even a bit weak’ to the upper tiers of power, brushing in the shadow of the wizard and cleric.

And bonus, that Vestige is spooky.

The actual text of the Vestige of Zceryll, from Wizards’ own web expansion, is pretty simple:

Zceryll was a mortal sorceress who communed with alien powers from the far realm. She became obsessed with immortality, seeking out the alien beings in the hopes of learning their eternal secrets. When she died, she became a hideously twisted vestige, forever seeking to re-enter the Realms via numerous artifacts she dispersed across the world. Zceryll grants you the ability to transform your body and mind into an alien form, granting you telepathy, resistance to effects related to insanity, the ability to summon pseudonatural creatures, and the power to unleash bolts of pure madness.

Okay, how is it broken? What’s it do that’s so good, power-wise? Normally when you talk about character power, you can usually point to something as a general rule – like you can point to the wizards’ spell list and that’ll explain itself. In Zceryll’s case, what you get when you channel this Vestige is:

Summon Alien: You can summon any creature from the summon monster list that a sorcerer of your level could summon. Any creature you summon with this ability gains the pseudonatural template. Thus, at 10th level you could summon any creature from the summon monster I-V list. When you reach 14th level, you can summon any creature from the summon monster I-VII list. You can only summon creatures that can be affected by the pseudonatural template. Once you have used this ability, you cannot do so again for 5 rounds.

Let’s simplify that: You can use Summon Monster (Half Your Level) every five turns at will. DMs may make you spend the action to do it, in out-of-combat ways, but at will summons is incredibly strong, not because you can flood the battlefield, but because summons are combat capable creatures that in many cases can cast spells. So every utility power available to any monster on the summon list is available to you, but in a spooky way. Need something big moved? Summon something big and stronk. Need to get out of a cage? Summon something that can move through walls. Need to wreck shop on the battlefield? Well at every tier, there’s a piece of cannonfodder you can dump on the battlefield and then not have to spend actions commanding. If your summon runs out of healing magic, you can just summon another one and get it to do the healing magic. If your summon is beat up, you can summon another one and get that to replace the other. It is one of the most startlingly effective spell families to have at-will access to, and the only real drawback for the Binder is that it’s a bit slow.

The actual theme of Zceryll is a weird one, and it bums me out a little that the Binder is a class ostensibly built around this variety of flavour choices, when every powerful Binder is going to be hard on Zceryll and the skills required to be good at managing Zceryll. It’s also frustrating because the name Zceryll is a person’s name first; the odd, hard to express mangled language of the name isn’t a language from outside reality – it’s someone’s name, a weird name, but it’s just… a weird name. It speaks of a culture that’s not common to you now, but Zceryll is still just a person, it’s not an extrusion of a reality where they don’t have vowel sounds.

I feel this is a dropped ball with Zceryll. At its root, it wants to be Lovecraftian; the powers are from the far realms, it’s about a refugee of our reality trying hard to get back in, it’s got this sort of lurking threat to it, and it shows you tearing reality open and letting in things that look like stuff you already know but which are definitely not, while you cast literal bolts of madness from your hand... and then disappointingly, it’s just… a wizard, like you, who drank of the outside.

My advice, if you’re going to use Zceryll in your game worlds? Soak in the eerie. Don’t say it was a wizard who started out researching the far realm. Make Zceryll something not someone.

3.5 Memories: Rokugan

Hold up.

I’m going to say some nice things about this book. I’m even going to praise some things this book does. I’m going to recommend you look to this book for examples of how to do a thing and I’m even going to talk about ways this game book set itself apart from an existing, flawed paradigm of D20 design for its period.

3.5 Memories: Tome of Magic

Magic in D&D is…

Is…

Look.

Let’s try and be nice.

3.5 Memories: Replacement Levels

Ever heard of this?

This mechanic, introduced in one of the Races Of books in 3.5, presented the idea that while the class structure worked in general for most of the game, there were more specific versions of classes for races that had a particular, peculiar affinity for that class. This meant that while halfling fighters and gnome fighters and dwarf fighters were generally all the same, a half-orc fighter might be different because of the way half-orcs did the job of ‘fighter.’

Continue Reading →Oaths, Pacts and The Moral Failure of Trying

A lot of D&D players view their D&D world like they’re a bunch of cowards.

Continue Reading →The Epic Level Handbook (3E)

When it comes to D&D books, you’re talking about what amounts to academic reference material. That’s not a slam on the game, of course – I’m not objecting to the games or the playability of the game, as if they’re now these dusty tomes that are only meaningful in a sort of hypothetical framework. It’s more that the books are literally designed to be reference material for a specialty field. These books are dense. That can present a challenge in giving someone who isn’t already versed in the game a way to understand that book. Do we talk about specific chapters? A point by point analysis? Do we look at just an excerpt?

I think in this case, at least for now, what we want to talk about here is an overview of the Dungeons & Dragons 3rd Edition Epic Level Handbook.

This book is a punchline.

Continue Reading →Karmic Twin

Okay, I said I’d only do a few 3.5 posts a month, so this one’s going to be a quickie. Back in that day, there was a special crop of feats you could get that you could take at level 1, which were made to try and give a character a feeling of their ‘background.’ These feats were first trialled in Dragon magazine, then a few were tested in the Player’s Guide To Faerun (that horny setting I talked about earlier in the month), and one source that really went hard on them was the Oriental Adventures and Rokugan sourcebooks.

Now wait, hold up, let’s just mention something here because if I don’t bring it up, someone will huff their cheeks and go ahah, gottim. Look, Oriental Adventures is the label on a door behind which you can find yikes, yes, of course, obviously. Doesn’t have to be, we have room for potential here, I really like this setting and stuff, there’s lots to like, but let’s not get caught up there.

Because the really funny thing here is a player behaviour, based around a single ‘Background’ feat.

In Rokugan, a General Mish Mosh Of Asian Cultures setting, you had Ancestor feats instead of Background feats, and they tied to historical lore characters and that was kinda cool as a way to encourage players who wanted access to mechanics to be aware of the lore of the setting. Good idea, good move, do that in your settings.

Anyway, one of the Ancestor feats was a Scorpion clan background feat, Karmic Twin.

Karmic Twin is a feat that is pretty gonzo on the face of it; you get effectively 4 extra points of Charisma for most non-spellcaster purposes, you get the ability to track or find a single person without any help and oh yeah, if nobody else in the party is your karmic twin the party gets an NPC whose story is tied with yours.

Leadership was one of the most powerful feats you could get, because it’d give you an NPC that was basically 2 levels below you and that’s an enormous amount of utility. Power, maybe, but just having someone who could synergise with you under your control was really strong. Karmic Twin gave you the same thing at level 1. Sure, some DMs might use it to inflict a lifelong enemy on you (and if they did, the charisma boosts were probably reasonable as a trade!), but here’s the thing.

My players used Karmic Twin and its cousin feat Sons of Thunder a lot. And every time, what they used it for was not for power reasons – the players overwhelmingly didn’t care about the mechanics of the other character.

But they all used them to get hot boyfriends.

Let your players have hot boyfriends if they want ’em. It doesn’t hurt things and the stories are more fun with players getting things they like in them.

3.5 Memories: Soo-Nee

I’m trying to limit my writing about 3.5 D&D and 4e D&D to maybe once a month, because while I do love doing deep dives into subjects there, they’re time consuming and I’ve found a variety of different articles is the best thing I can do to keep my audience engaged. Plus, it’s a great kind of ‘content well’ where you can grab a book from the game in question, leaf through it, and find something to talk about – inevitably.

In this, Smooch Month, though, what content is there in 3.5 D&D to talk about that I haven’t gone over with a discussion of ‘roll to seduce?’ Lords knows we don’t want to talk about the way sex and romance are normally represented in D&D, because they’re mostly only ever brought up transgressively. We did the Book of Vile Darkness already!

Still, it’s smooch month and that means that while we may be talking about romance and relationships, there’s always with that aftertinge of ‘horny, maybe?‘ that I circle around and avoid, and when the time comes to talk about horny, maybe and D&D, there’s really no place to go but the Forgotten Realms.

If you’re not already aware, Ed Greenwood’s Forgotten Realms setting is a place full of lots of different interesting countries (I’m trying to be nice) which are perhaps known for a pattern of having an elderly, cranky wizard in an important place that’s secretly guiding important political events and enabling adventurers. You might know it as a setting which has a large number of prominent women in positions of authority in some important, adventurer-centric places, meaning you may have a fond memory of being sent on an early quest by Aribeth.

It’s also perhaps a little less well known for being a setting where under the hood Ed Greenwood was fantastically horny and has definitely, definitely dedicated lots of time to thinking about the sex lives of those characters. Once you know about it, it just kind of lurks there like a fog at ankle-height, clinging to everything.

Now, something else about the Forgotten Realms is that Ed Greenwood started writing it in 1967 and pretty much has never stopped, filling the world with ever increasing levels of detail, conspiracies, political introgue, cities, townships, lodges, orders, empires, dragons, really racist drow stuff, and of course, gods. That brings us to the book I flipped open this month, Faiths & Pantheons.

If we’re talking about a love domain (and boy there’s a lot bound up in that conversation which I largely want to leave alone, but suffice to say fucking sigh) then why not look at the Forgotten Realms’ goddess of love, Sune?

Sune as a goddess is a bit standard. She’s a beautiful feminine woman, her descrpition includes how her lips are plump, how she dresses in ‘near transparent clothes,’ all that standard stuff. She’s a redhead, which I mean, you can make a case for any of those typical looks and what they encode, but the real basics is that Sune is a Hot Goddess of Hotness.

The descriptors of her goals, aims and dogma are all extremely in this vein, with a drop of how thanks to recent reforms in her church, women only outnumber men four to one. Her temples are described as public salons and bathhouses, with diaphanous robes and beautiful clergy and mirrors all over the place. Sune even communicates with you via mirrors, where you look into them, she changes your appearance, and then talks to you through your own, now hotter face.

Now, one thing in favour of this setting, and this character, is that Ed Greenwood has gone on record that Sune (and everyone good in the Forgotten Realms) says Trans Rights, so that’s something and that’s all we need to talk about there.

Sune’s a goddess of love, lust, pleasure and protection and it’s so weird that as represented, her faithful mostly seem to hang around taking care of people and not doing adventure stuff. They even talk about how commonly the Heartwarders are pacifists, and how this means that enemies often are reluctant to attack them, which let me tell you, that’s not how that tends to work.

What else has Sune got going for her? If you’re not getting sent on quests by the Goddess of Love to do things like smash tyrannical families that are keeping star-crossed lovers apart or destroying churches that are trying to control people’s expressions of love or pleasure, or even just building safe spaces and standing in the doorway with a sword, what else has she got going on, why worship Sune?

Girl Hot counts for a lot, right?

When you get a Player’s Handbook you may see the five or ten gods presented there and think that the power of a setting is built around gods of punching, fierceness, and maybe evil punching, and that’s certainly a place to start. As the pantheon of the Forgotten Realms built out, Ed expanded into things like racial pantheons, where elves have a bunch of their own gods, and maybe other races have whole bunches of other gods, and with that came the need for more things for gods to be about, represented by more domains.

Sune, therefore, required (?) the creation of the Lust Domain.

It’s not great.

I’m trying to avoid talking about the way you may frame enchantment spells or diplomacy checks in your game, but the good news is that you don’t need to worry about what the Lust domain does in any given 3.5 game, because it’s really bad and the Protection and Pride domains are right there. Okay, so she’s not setting the world on fire mechanically. What else is Sune bringing to the table?

Another mechanical space that these gods open up is the idea of prestige classes. This was a really good idea, because it served two possible purposes for player characters. If you liked Sune, you could look at her prestige class and get a feeling for the kind of mechanics she liked; if you liked the mechanics of that class, you could look at Sune and see if you liked that direction for your character’s personality.

Sune’s pretige class is the Heartwarders, which is a basket of yikes. This class increases your charisma (very rare to get like this, but not hard to get at all), gives you a ally buff power by kissing them (which also is so amazing a kiss it dazes them, meaning you can actually make them worse off), and lets you create holy water love potions by, um, crying. There’s a lot bound up right there in what a person sees as being beautiful or aesthetically resonant. The class is pretty broken, because it still lets your cleric be a cleric, but as far as stuff you can bolt onto an already-broken class goes, this one’s not worth what it gives you!

It’s a shame, because a rose-coloured knight of love and rage seems like a great character concept to defend the worshippers of a god of love. Someone should make a much better version of this idea.

And that’s Sune! A Goddess of love and lust in a subtly horny world. And if you’re like me, you were today years old when you learned this name is instead pronounced ‘Soo-nee.’

Bad Balance: Races of Destiny

I’ve made fun of Dungeons & Dragons 3.5 a lot, and I do it because it’s easy, and fun, and it’s funny, and let’s do more of it.

There were two sets of the first wave of expansions for 3.5, the class style books, known as the Completes, and the race books, known as the Races of books. The Completes touched just a tiny bit on the early days of the class role system – with the first wave being Complete Warrior, Mage, Psionics, Divine and Scoundrel, but expanding into things like Adventurer and Champion. The Races Of books gave you a run down of three races at a time, linked by a common theme, and that was a theme that was routinely straining at the edges. Halflings got treated as a ‘race of the wild,’ and gnomes as a ‘race of stone,’ as opposed to their proper place they shared of ‘races of hobbits fans.’

No time for gnomes or halflings, me, I know.

Continue Reading →3.5 Memories: The Kaorti

Now, while I may be on the record saying that Dungeons & Dragons can do horror scenarios, doesn’t mean I necessarily agree with the way that the default books angled towards horror. One can point to the ‘mature’ Book of Vile Darkness (more like vile dorkness, boom, gottem) that tries to be shocking and edgy and it’s just kind of insulting and basic. But the BoVD wasn’t the only book of its type that tried to be creepy and horrifying, nor was it one that strived to be mature.

For example, the Fiend Folio is the only book I own with nipples.

Here, check it.

After this point I suppose it only bears to mention: Content warning, creepy monsters and horror imagery after this point.

This book is also trying to cover a lot of bases, with some artists getting quite a lot of work which I feel, though can’t say for sure, is a product of some artists being very productive in a short period of time and that being used by the art director. Like Thom M Baxa, who produced a bunch of work in this book which is meant to represent a lot of different things but mostly just seems to represent Just Thom M Baxa’s work.

Continue Reading →3.5 Memories: Psionics

Maaan, this system was cool.

Okay, so it’s twenty years old or something so I’m assuming you don’t really know what this was or how it worked. Psionics was one of those things that D&D 3.5 seemed to pick up because it was in 3rd edition and there was something similarly back in 2ed and then going back. It was never something the rules prominently featured, and was always meant to be its own little contained system that ‘couldn’t work the way that spells worked. The older systems, back in 2ed used ‘power points’ instead of ‘spell slots,’ you know, one of your rudimentary mana systems.

These required rules, coupled with the way they were sequestered meant that the Psionics systems got handed off into a small number of books, which were focus work by a small number of developers who not only really cared about them, but weren’t competing with anyone about it, like the core rules’ Druid, Cleric, Wizard and Sorcerer problems were.

The result is that the Psionics system is made up of a smaller number of powers that have to be flexible, because they just weren’t going to get a lot of different psionic powers the way that every different version of a fireball got to have its own fancy special effect.

It also meant the psionic powers had to be designed to scale much better than the spell system; rather than the tight restrictions of spell slots that force you to wind up collecting a large number of choices, and be aware of all of them as the best least tool for any job, you instead had the powers that you could do, and the choices were made at use. You could spend points to make your powers scale, and you could even choose the way they scaled.

That meant that yes, you still had fiddly spells, but you chose how fiddly they were, how fiddly they could get. You could pick your powers to get a wide variety of oddball stuff, or you could focus on a consistent theme, using your power choices to make one power you were absolutely great at, and small utility powers to go along with it.

There was something to the aesthetic of it, too. Rather than your typical wizards and robes and swirling lights, Psionics played in a realm that was more purple and crystals, with a sort of Cthuluhoid Lovecraftian horror to the enemies. Rather than drawing on the idea of old lore and ancient history, of things written in books, the storytelling of the psionic character was more tied into really primal knowledge, things that were born out by doing rather than learning.

This still put the books in some odd places, of course; mechanically, there still needed to be wands and scrolls, because those were considered essential parts of balancing the needs of a flexible spellcaster, so there are Dorjes and Power Stones (or ‘sticks and stones’ as they were known). There were psionic dragons, because of course you need dragons, and their gimmick was, well, they’re dragons, but they’re psychic.

Yet when I think back on this system, a thing that really sticks with me is how in 3.5, there were just so many builds you could make for psionic characters that weren’t constrained the way that wizards and clerics were. You could afford to lose a caster level or two, you could pick up other effects to build on what you had. You could share spellcasting skills between different psionic classes, and there were interesting, oddball prestige classes that gave you a niche, interesting way to craft your character.

Normally when I think back on 3.5, there’s a pretty clear hierarchy system that kicks in. Fighters form a sort of basement where everything that’s worse than it is seen as really hosed. Then there’s the crew of weird classes that aren’t bad for any specific reason, but because they have a niche that usually can be replaced by a spell from a wizard. Then there’s the really good renewable resource types, the powerful melee hitters, the prestige class complex builds, and then there’s the spellcasters, and then just at the bottom end of the spellcasters there’s the rogue and some gish, I guess. It’s a complex space and most of them, the best thing you can do is one thing.

But when it came to psionics – classes that mostly sacrificed variety of effects for flexibility of application – there were just so many different ways to build, just based on the powers you took.

Kinda preceded the Book of Nine Swords, too, and formed the foundation for the way 4ed worked.

Huh.

Funny that.

3.5 Memories: Heroes of Horror

When you sit down to play a game with your friends, you are ultimately looking to have an experience. That experience can be built around so many feelings, so many ideas, and it is just as valid an experience to seek out the tension and catharsis of a horror scenario as any other. The horror campaign, the macabre fantasy, the tangle of feelings you get when you find yourself pressed in the thorns and consider how much you’d give to just escape, even if it means leaving behind a little of your soul – this is absolutely something you can do in tabletop games.

It’s not even at odds with Dungeons & Dragons’ vision of heroic fantasy, which we can argue about, or wait, no, we can’t argue about it, because I find having to define the narrative parameters of a heroic fantasy or really deal with people who want to try and define the ‘genre’ of a game that’s as broad and flexible as D&D to be a task more akin to pulling teeth than having fun. Accept then that it is entirely possible to run a horror game using Dungeons & Dragons, because even if it’s not to your standards of horror doesn’t mean it doesn’t deserve to wear the genre label.

And Wizards of The Coast recognised it too, releasing the 2005 supplement for D&D3.5, Heroes Of Horror.

This book is, let’s say it reaches the lofty purchase of fine, I guess. I’m not wild about the content it offers (in no small part because my players have been horrified by things I made without any such guidance), but I’m also not against what it’s doing for the most part. Particularly nice is that the book contains an attempt to discuss player boundaries and emotional needs, even if it’s a very surface, a very 2005 discussion of those boundaries. I was going to give this book a treatment, only to find I already did a thread on it, and then saw how that thread kind of cooked away into just making fun of one thing in the book.

Even while the book is a thorough examination of a theme space, it’s not all one way of looking at it. There’s talk about player options, about how to handle ideas of tainted powers, kind of a Moorecocky thing. There’s some monsters meant to be more horrifying, there’s some discussion about the use of the inexorable, about the notion of the destruction or opposition of hope itself as component of horror. There’s also some horror scenarios, which I’ll admit I don’t find very engaging because they start at ‘murder clown mind-controlling orphans,’ and I don’t really need any kind of special rules to treat clowns as kill-on-sight targets in games. They’re up there with viziers.

Nonetheless, this is a 3.5 book and what that means is at least somewhere, you’re going to find a big list. In this, the list is a gigantic, 100 entry list of what it calls Creepy Effects. These are meant to be things you can dot into the game to give players a feeling of something unsettling being afoot.

There are three problems with this list. The first is the kinda fucked-up time issue; some of the list’s things can be singular moments, abrupt and dramatic arrests in the vision they have of normal – all the wildlife in an area falling silent to no effect, for example. Some of them are long-term problems, like fiding a persistent object you were sure you disposed of. These events aren’t really comparable – one is best when it comes out of nowhere, the other requires regular poking and prodding to make a repeated effect.

The second problem with the list is how many of these ‘creepy’ things are in fact very ordinary. One creepy happening is meeting a person who has a voice like an adult, but are as tall as a child. That is to say, meeting somone short. Another is a player hears something that none of the other players hear, which is a really common real-world experience, not to mention hearing voices or smelling smells nobody else notices. I get it, it’s horrifying to experience those things if you’ve never had to deal with doubting your own perceptions, but for people who have experienced that, it’s just kinda a reminder of how precious the writer must be. There’s also a bonus point here: in a world where there are Sending spells and Psionics, how is it weird to hear a voice? The real trick is trying to work out who sent the messages.

Finally, the third problem is this table ends on the entry: One Word: Fog, which made me laugh so hard it broke all chance this game had to ever act like it was going to lead to spooky games ever again.

3.5 Memories – The Dragon Girlfriend

Time to time I’ll talk about things in Dungeons and Dragons 3.5 about the fairness or brokenness of various things like I’m some kind of specialist scientist with a really niche interest and people around me are reasonably familiar with what I’m talking about but don’t actually understand the magnitude of what I’m talking about. It is, I imagine, the kind of blank look that civic engineers get when they start describing ‘tolerances’ to city planners, or a nuclear physicist trying to explain control rods to a Wendy’s drive-through, just with stakes that are infinitely lower.

Here’s a thing, then, that’s just there, in the rules, and it’s really powerful and it’s silly and it’s invisible. It’s invisible because it relies on a dice roll and the game rules work at it, and the rules as written just seem to stop, like someone didn’t consider that anyone might actually use this ability.

Clerics could get domains. These were things that’d make your character feel more different, more distinct from anyone else. Hypothetically, this meant that a cleric of Time and Elf would look different to a cleric of Fire and Law, except what usually that meant is you got a lot of clerics of Luck and Time and Elf and Glory, and if the player was just a well-meaning scrub attracted to some good looking keywords, maybe even Strength.

Anyway, mixed in amongst this there were the innocuous-seeming Fire, Water, Earth and Air domaints, which gave you the ability to, as in th example of the Water Domain: Turn or destroy fire creatures as a good cleric turns undead. Rebuke, command, or bolster water creatures as an evil cleric rebukes undead. And that sentence sat in the player’s handbook like a god damn rat trap.

Because what does that mean? What does a ‘water’ creature mean. Well, a water creature is any creature with the water subtype. Which obviously means things like a water elemental, and that’s not such a big deal, right? Those creatures tended to be kinda basic; single special ability, a bunch of immunities that won’t protect them from much, but they would come along and maybe a cleric could have a fun time with their new pet. No problem, right?

Here’s the thing: The rules don’t put a duration on controlling undead. Controlled undead, in all the situations you see them, operate at the order of their controller, but act on their own initiatives. And that’s something you have to dig for: A player character with controlled undead will generally be allowed to boss them around freely because 3.5 was not a place that had a good handle on what we call ‘an action economy.’ Okay, so a Commanded elemental creature is great because it’s free actions, right? That’s a problem right there.

The other thing is, though, ‘water’ type creatures aren’t just ‘things made of water.’ It’s a whole galaxy of critters that have the Water subtype. And that means that suddenly the entire Monster manual opens up, and it doesn’t specify nonintelligent water creatures and that takes, if you start from the top down, into the home of the dragons.

Yes.

Two dragons – Black and Bronze – are ‘water’ creatures.

You get a lot of bang for your buck out of a dragon. A level 5 cleric can command, with a reasonably good roll, 9 hit dice of Dragon, or a Medium Bronze dragon, which has six attacks at +11, an AC of 18, 76 hit points and a breath weapon. A level 8 cleric with a pair of baby bronze dragons flapping around them would be a cute thing to see, and in terms of sheer bulk you can put on the battlefield, it’s pretty stunning – a level 8 cleric is looking at having something like 45 HP, and those dragons would have the same, so this one class feature with a good roll can triple the amount of meat you put on the table.

What’s more, this is without any weird stuff. This isn’t pushing the limits on what your domain can do. This isn’t using magical items to improve your turning (and you absolutely can) or feats to improve your turning (and you absolutely can) and this is without involving the other types of elemental domain (and red dragons have the fire subtype), or even taking both and getting to command your hit dice + 4 of water creatures and your hit dice +4 of fire creatures!

Did I ever see anyone do this? No.

Nobody bothered. I mean, clerics were broken enough without it.

You could ignore a class feature that let you control dragons because… eh.

You had better stuff to do with your time.

I always wanted to give it a shot, and make a character who used it to have a water dragon girlfriend that followed them around? But any DM would look at it, despite the way the rules said it worked, assume it didn’t really do that, and then the whole idea got vetoed. Which really, it should.

And this is just one feature of one domain from one class that’s so broken it can ignore this.

3.5 Memories – Vileness

You know it’d be pretty easy to draw the conclusion, based on the way I talk about it, that I didn’t like 3.5 D&D. This couldn’t be further from the truth – I haven’t played the game in ten years and yet I still have all my books, still have character sheets and build articles and all sorts of interesting work I did. I wouldn’t write these articles about 3rd edition books and mechanics where I reminisce about how the things I did – silly as they were – were still cool. I liked 3.5.

But gosh did it make it hard.

Owlbear Traps

In the past I have remarked upon the idea of Dungeons and Dragons 4th edition’s quality as it being a game that lacked ‘bear traps.’ This is just a basic metaphor, you know, comparisons between a thing that could hurt you hiding in an undergrowth, that you might never realise was there until after it hurt you? It wasn’t ever meant to be a genuine game design term, not something I’d use in serious discussions.

Yeah except now I’m using it and I need to nail down that to make sure people might know what I mean, and I’m going to be very specific here. I’m talking about Dungeons and Dragons 3rd Edition as examples of game design, and I’m talking about the overall philosophy of the game.

Dungeons and Dragons 3rd Edition did not mind or care if you had a bad time that was the game’s fault.

I’ve spoken in the past about the sorcerer and the wizard; the tension that lay between two classes that were very similar, with one just being markedly worse than the other, and the competitive design mindset between them. I’ve also spoken in the past about how there’s this class, the Druid, where they have a class feature that’s about 80% of everything that a Fighter is, and how over time, that class feature improves faster than the fighter, resulting in overtaking in the mid-game.

The big issue of 3.5 class balance is that melee combat was, just in general, not as good as magic. Ranged combat wasn’t that good either, but it could be made to compete with magic, mostly through the use of magic. The best archers in the game were inevitably spellcasters using magic to compensate for what the fighters and rangers were given, and still had their spellcasting besides.

This is something of the philosophy of this game, where it wants it to be possible to mess up building or playing your character. It’s a way to represent ‘being good’ at Dungeons and Dragons. Which is an interesting idea, and one that I kind of want to support, on one level. I think games are better when they’re made as sequences of interesting decisions; deck-building in Magic: The Gathering is an interesting decision, and that doesn’t make the game play experience of it that different. Heck, you could view a draft, then a deck build, then the matches of Magic: The Gathering as multiple different games, with all sorts of interesting decisions along the way.

The problem is that an evening of drafting for Magic: The Gathering is maybe four hours and you’re done while building a Dungeons and Dragons character in 3.5 required an enormous investment in time because you could only level them up as the game progressed.

It’s also gatekeeping: The game wants to give you the means to screw up at it, because the idea is that doing well or making smart choices is more satisfying and rewarding. Except your character, their feats and their powers are not a small choice; they grow over time based on your experience playing a game and may take months or years to come to fruition. You might need to read dozens of books to get a handle on how a character really works – the full breadth of a character may be dozens of books, some of which are totally unrelated.

This game presented you with choices of varying difficulty, but you needed enormous context to know how those choices worked. And you had to master the system to ever appreciate how bad some of the choices were.

And thus we have an owlbear trap: A way in which Dungeons and Dragons 3.5’s design philosophy prioritised servicing an enfranchised, qualified group of players in order to make it tangibly more desireable to do the things those players liked. Or to simplify: An owlbear trap is when you make it possible for new players to fail, just because they’re new.

The Dwarves Wrote The Histories

An idea I’ve never been able to shake is the D&D racial animus between dwarves and orcs-and-goblins 3.5 D&D presented. This is an idea that stems basically from your Tolkein source material, but it has a weird side effect when you interrogate it, because of time.

Dwarves are so good and so used to fighting orcs and goblins that they have all got an advantage at it. Like, this is stuff baked into their culture so deep their pastry cooks and their ponces all know how to lay into an orc a bit.

Look at this chart (obtained from d20srd.org):

| Race | Middle Age1 | Old2 | Venerable3 | Maximum Age |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human | 35 years | 53 years | 70 years | +2d20 years |

| Dwarf | 125 years | 188 years | 250 years | +2d% years |

| Elf | 175 years | 263 years | 350 years | +4d% years |

| Gnome | 100 years | 150 years | 200 years | +3d% years |

| Half-elf | 62 years | 93 years | 125 years | +3d20 years |

| Half-orc | 30 years | 45 years | 60 years | +2d10 years |

| Halfling | 50 years | 75 years | 100 years | +5d20 years |

Ignore the halflings and elves and all that, we’re focusing now on the Half-Orcs and Dwarves. Goblins in the Monster Manuals are said to live a variety of years, depending on which one you read, but they tend to hover around 30 to 40. Orcs and Hobgoblins have a similar range, and Races of Destiny presents a Half-Orc’s lifespan as capping out at an absolute max of 80. By comparison, a dwarf’s maximum age is 450.

A dwarf, by middle age, has seen the rise of nine orc or goblin generations.

Consider what that means to humans. If I fought the man that killed my grandfather when they were both young, that man would be old, now. In this case, an orc facing the dwarf that killed his grandfather is facing someone who time has not weathered at all.

What’s more, the reasons, the motivations for doing so – they’re not around. When you look at how these books present orcs, goblins and dwarves don’t have cities or civilisations; they have things called warrens and camps. They’re presented as being kind of what we’d normally consider ‘pre-civilisational’ and that means they don’t do things like agriculture or writing books that tend to be how we, as people who do agriculture and writing books consider a hallmark of being ‘real’ cultures. Let’s set aside the obvious bias here, and just look at the effect. It’s going to be very hard for these Orc and Goblin cultures to have clear records of what happens when they have wars with the Dwarves.

They don’t have maps or border or maybe even the concept of a country. They’re typically represented as illiterate and use a script that’s not even their own native tongue to write in when they do. They don’t get to know why the dwarves rolled in, but the dwarves do. It’s one of the most obvious things about the dwarf culture as it’s represented: They are old, and they are stubborn, and they remember old grudges.

From the perspective of the orc, the dwarf is an implacable unstoppable juggernaut that emerges from the mountains to kill a generation for reasons that are never truly scrutable. Their armour and weapons are older than your civilisation. They are like cataclysmic storms.

And the dwarves have been doing this for so long that everyone knows how to fight an orc.

Everyone.

And the orcs and goblins and hobgoblins don’t get a bonus against the dwarves.

Consider who’s telling us these stories; the people with their forts and their steel and their axes and their maps and their records who teach their members to murder goblins and orcs and hobgoblins that they never have met and never have any reason to meet. A clockmaker isn’t going out of their way out of the fortress to go forage around in dangerous hobgoblin areas for gear parts. But he knows how to stove an orc’s head in.

Here’s your lesson, game-design wise. These decisions were all made to reinforce flavour from a fiction: In Tolkein’s books, dwarves and orcs were at war, and dwarves were player characters and orcs weren’t, so dwarves got a bonus to help players who play dwarves be excited to fight orcs. The ages follow through from Tolkein too – created monsters like the orcs don’t need a culture, they’re just there to be fought, so it doesn’t matter if they’re short-lived. They’re a byproduct of someone else’s war machine. Dwarves are meant to have long kingdoms and take a long view, so they have to last longer than humans. It all makes sense.

But the mechanical choices made here to represent this flavour create an eerie kind of genocide-capable culture that seems to exist to punish a nearby stone age culture for crimes that culture may not even understand as crimes.

These dwarves seem like they’re really bad, to me.

The dwarf-goblin header art is from Jeffry Lai on deviantart

The bumper image is the cover art for Battle of Skull Pass, which best as I could find was by John Blanche

Rebuilding Cobrin’Seil Part 4: The Everywhere Else

Back in 3rd edition, I created my own D&D setting. It wasn’t very good, but I’m still very attached to it, and want to use it as an object lesson in improving. I also want to show people that everything comes from somewhere, and your old work can help become foundational to your new work.

Content Warning: Some of the old text is going to feature some unconscious cissexism and sexism, and I know there are a few unknowingly racist terms that I used.

Alright, so previous bandaids were about my decisions that were thoughtless and badly thought out, like ‘Kyngdom’ as a name, or barely scrubbing the name of Cimmura. The thing is, Dal Raeda, the Eresh Protectorate, and Amenti represent what are some of the best designed pieces of the setting, the places where I had good, fundamentally usable ideas.

The rest of things is where it all gets a bit soft, and also where I did some things that are uncomfortable, and now with the benefit of experience, I realise are pretty damn racist.

You might have notice that I’ve avoided showing any maps of this world, because it’s all in flux now.

Continue Reading →Rebuilding Cobrin’Seil Part 3: Framing Spaces

Back in 3rd edition, I created my own D&D setting. It wasn’t very good, but I’m still very attached to it, and want to use it as an object lesson in improving. I also want to show people that everything comes from somewhere, and your old work can help become foundational to your new work.

Content Warning: Some of the old text is going to feature some unconscious cissexism and sexism, and I know there are a few unknowingly racist terms that I used.

The standard D&D place write-up is bad.

When I first wrote this setting, I did it by emulating the existing 3.0 and 3.5 D&D sourcebooks’ ways of representing countries. It’s a good practice, certainly as far as making sure that as a developer I was making games to a professional template, but it meant that things that template did that I don’t like, I was doing anyway.

Continue Reading →Rebuilding Cobrin’Seil Part 2: Knightly Orders

Back in 3rd edition, I created my own D&D setting. It wasn’t very good, but I’m still very attached to it, and want to use it as an object lesson in improving. I also want to show people that everything comes from somewhere, and your old work can help become foundational to your new work.

Content Warning: Some of the old text is going to feature some unconscious cissexism and sexism, and I know there are a few unknowingly racist terms that I used.

I mentioned last time that I like giving players handles. In the country now known as Dal Raeda, this took the form of different provinces, with different cultures, but since a game set in Dal Raeda meant I’d be dealing with the lead-in to a potential civil war or players subverting or delaying that civil war (and that seems a big setting piece to deal with in my first game or two), I immediately relocated my focus to the nation next door.

Continue Reading →Rebuilding Cobrin’Seil Part 1: Names in the Kingdom

Back in 3rd edition, I created my own D&D setting. It wasn’t very good, but I’m still very attached to it, and want to use it as an object lesson in improving. I also want to show people that everything comes from somewhere, and your old work can help become foundational to your new work.

Content Warning: Some of the old text is going to feature some unconscious cissexism and sexism, and I know there are a few unknowingly racist terms that I used.

First of all, let’s talk about just some basic work of names.

One thing I feel gives players a good handle on things is giving them groups and places to feel they can ‘belong’ to. These are player anchors, and players love those. It’s why class-race characterisation has lasted so long and so well, and why people use it when describing games that don’t have classes or races. Handles are great, and they’re part of how we tell stories and anyone who tells you they work against good storytelling is unimaginative, fight me.

Continue Reading →Rebuilding Cobrin’Seil

When I was nineteen, I started running Dungeons and Dragons. The history of my time with this game isn’t important, but what is important is that when I started, I had access to the setting books of the Forgotten Realms and Greyhawk settings, and seeing this veritable library of game rules and information about mechanical identity and culture, I immediately said No, I don’t want that.

I wanted to tell stories with this game, but there were two reasons I wanted to avoid an established setting:

- I was brand new to the game, and didn’t want people to feel they could ‘beat me’ about the world by bringing up a book

- I didn’t want to have to read a dozen books to get started

Instead, I invented a world in a weekend and then spent years bolting on new things, editing, re-editing, retconning and then, around the time 4th Edition became a thing, I quietly put the world away and worked on other stuff. I still ran the occasional D&D game in this world, but the world wasn’t important to the games.

This is a huge trove of lore and game mechanical information. I made classes and races and feats and just a ton of stuff, some of which I recently dusted off and looked at, and you know, some of it was bad, but some of it surprised me. Particularly, a thing that surprised me was how many of the basic ideas in it I liked, and wanted another chance to do better.

Plus, I know there’s an interest in worldbuilding as a skill, and I’m friends with some people who are really good at it, and they’ve had some really interesting stuff to say about it. But I don’t just want to make good things and show you the final product; instead, I want you to see that every good thing you like was worked on and refined and changed, and for that reason I figured I’d put down these setting revision notes here, in a series.

This is going to introduce you to the setting, both how I’d explain it to a player, and how I’d put it into a book. I’m going to examine my ideas, and then examine how I think players might engage with them as play spaces.

Going back over old writing is going to reveal some ugly stuff, and some really basic stuff. I imagine there’s going to be some implicit racism and cissexism, some unconscious misogyny and I know at least once I use a slur as a game term, which isn’t good. A content warning then, going forward.

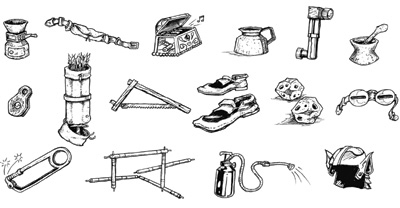

The image is from the VGA Remake of Quest For Glory I, a game that heavily influenced the creation of this setting, even if I let almost none of the Cole’s taste for Whacky Humour infiltrate my game.

3.5 Memories – Singh Rager

Sometimes playing Dungeons and Dragons 3rd edition was like playing a game under a Mexican standoff. Part of it was our maturity as players and part of it was a very programmatic view of the game rules. There was a fairly widespread, commonly seen vision that there was a correct way to play the game, and you could use precedent and rules and various senior authorities to make your position the correct one. The thing is, these arguments weren’t fun and they’d eat all day and you’d get sick of them, so you wanted to avoid them.

What’s more, the game was so big that it wasn’t very easy for a DM to be sure about what their players could do, and it was often very awkward to roll with it when a player did something unexpected. If you were particularly strict about things, you’d sometimes watch as the game juddered to an almighty halt as you nerfed a player in-action, putting your foot down at the right moment to make a player feel bad. Especially bad when players had common goals, but you had to reign one in while leaving the other unrestrained. Rightness of it notwithstanding, it felt bad.

It wasn’t like the design didn’t encourage this kind of mindset, too – there were all sorts of monsters which were made explicitly to shut off particular abilities of player characters. Golems often were immune to magic in all but extremely specific ways, many monsters had totally unreasonable damage reduction or really weak saves in one category, and that was meant to represent a way that the players could prey on weak points, or, that you could punish players for their failings. DMs knew they had ‘the nasty stuff’ they could bust out, and it was stuff that almost never had any meaningful reason to be the way it was. You didn’t need to put Gricks anywhere, Gricks didn’t have powerful resonance. You didn’t need a Golem, representing a wizard’s hubris, you could just use all the other more interesting things wizards could do. Wizard players would never flipping bother with making a golem, too.

DMs stayed away from these things unless the players got uppity, and the players, in order to avoid arguments, tried to avoid getting uppity. One of the easiest ways to get uppity was to show off that you could exceed the challenges presented by the DM – which really, in hindsight, is such a silly thing. If a fight’s over fast, just implement that knowledge for next time.

Anway.

What this meant is that if you wanted to min-max, you kind of wanted to min max within boundaries of what the DM could handle. Combat was a good place to stay, because even the nuttiest combat build still tended to be limited by where it could physically stand and how many actions you got in a turn. Wizards could sidestep entire combats with utility spells, or scry-and-die boss monsters. Clerics could make armies and take over dragons, and druids were all that on rocket skates. The Artificer and Archivist waited nervously in the wings, hoping nobody would notice them, because they were somehow more busted than the other spellcasters.

If you wanted to min-max a melee combat type, though?

Well, boy, you could go buck. wild. there and it wouldn’t really matter too much. The most broken melee combatant in the game you could make was probably a wizard or cleric, after all, so if you got there without doing any of that nonsense, you were usually seen as ‘playing fair.’

So let’s talk about the Singh Rager, a 3.0 orphan that got nerfed by 3.5, and was good enough even after the nerf.

Game Pile: Lords Of Madness

I rarely hold up Dungeons and Dragons books as being good books for general gaming purposes. They’re all very much books about Dungeons and Dragons, and even Elder Evils, last weeks’ offering for campaign-ending threats, was a book jammed full of systems for explaining weather, big dungeon designs and complex fight mechanics. When you bought a book for Dungeons and Dragons 3.5, you were often getting a book that was some 30%-50% system information, information that’s dead weight if you’re not using that system. Some of my favourite books from that time, like The Tome of Battle and Races of Eberron are absolutely steeped in mechanical information, and if you’re not using it, you really aren’t getting enough book for your investment to be worth your time.

But let me show you a book that I want to recommend to anyone making or playing with horror even if you don’t want to use D&D or even fantasy settings, that also has the on-theme matter of being a spooky book about spooky stuff. I don’t mean Heroes of Horror, which devotes a lot of its space to trying to systemitise horrifying things, no. I want to talk to you about a book about putting things in your world that are horrible.

I want to talk about Lords of Madness.

That said, I would issue a content warning, beyond the typical this is a book about spooky stuff. This book has a lot of humans being eaten, brain parasites, descriptions of people being seen as prey, but all that stuff is very passe for D&D monsters. Here be tentacles, goop, puppeteering and meat.

The other content warning is that if you’re Dissociative or plural or have DID or any of the related fields of mindset complication, Lords of Madness attempts to write numerous ‘alien’ psychologies that may look familiar to you, imagined as alien othered.

I’m personally reluctant to use the term ‘saneism’ because I don’t feel qualified to make that call, but there’s a lot of language in this book that assumes a very simple mental health binary and puts things like plurality or low-empathy living in the ‘bad’ bucket. Note that this doesn’t really take into account that most D&D adventuring parties are composed of homeless murderers.

Game Pile: Elder Evil

Part of the challenge in finding horror topics for this month has been finding game related things that I found actually legitimately horrifying. Things that I found creepy, things that I found that were capable of giving me that prickle on the skin, rather than just wearing the trappings of the horrific. There are lots of horrifying videogames, lots of games that want to be horrifying, but so few of them really make me feel it.

Let me show you then, the book that heralded the end of the world for 3.5 D&D, and went out with a howl.

Bad Balance: Pissing Contest

Back in D&D 3.5 there was a really weird balance problem that existed within the confines of “two of the most powerful classes” that were nonetheless so different in power that one of them was definitely a weaker option.

Let’s talk about wizards and sorcerers.