July 2019 Wrapup!

July’s over! Yay!

This month’s had quite a lot of that good Tabletop Gaming Content, with posts about The 3.5 Book Of Vile Darkness, about the process of making a game like Halls In the Mark, the way that D&D gatekept through complexity in Owlbear Traps, the view of violence in Vampire: The Masquerade. Far and away, though, the most popular article of this month has been The Dwarves Wrote The Histories, where I talk about the way that dwarf mechanics in 3.0 and 3.5 D&D paint an unspoken one-sided history. Also popular was The Dragon As State, where I talk about how dragons represent things and we can use that in stories.

This month’s video is half of a two-parter; I plan on uploading the other half next month, because even if it’s not in-theme, it’s still a thing I started, so I want to finish it. One of the problems with this kind of content is that I know it’s not very high demand compared to things like the Meatpunk and Heterotopia essays, but it’s much, much easier to make by comparison, and it’s good practice for free speaking, instead of scripted stuff.

Now, part of this is a function of how much of my writing time is dedicated to the big job of my uni work these past two months. That’s going to change a bit but not as much as you might think.

This month’s shirt, UWUNIONISE is a tribute in part to my friend who is very squishy and lovely but also extremely good and tough, and the plight of the tech worker striving to unionise

This was the month of SMASHcon, which is an Australian anime convention that has nothing to do (inherently) with Super Smash Bros, but that didn’t stop all the questions I got being about that other con that’s a different time and in a different country. Great SEO from our parties, I guess.

That meant we got Con Prep into Con Crud. This month also saw writing on my PhD intensifying, and meetings about the next semester. It’s all been a bit of a blur, and my general mood has been pretty down. There’s been a lot of people who need someone, if only for a few minutes, and it’s been extremely wearying. Also, despite the fact I normally sleep better in winter, I just haven’t been getting to bed at good times this month.

Sorry, sometimes it just sucks.

Making A Big Flag Thread

If you don’t follow me on twitter, and in that case, I’m genuinely surprised you’re here at all, though, thank you, hi, you might be unaware that in May and June I did a long exercise in posting critique of every city flag in America I could find, doing – generally – one state a day for a whole month.The intention was to archive it, on this blog, like I wound up doing for the state flag thread. This is good for me, because it means the work isn’t as ephemeral as it is on twitter, and I get some easy blog posts already made, and it’s good for you, because it means you can actually find the things by searching this central repository of my writing. Win win.

The problem now is scope. See, the state flags were broken up over a week – fifty flags, five days, that more or less worked out. The twitter thread though was an hour a day – more or less – every day for a month. And the number of city flags vary wildly between states – Wyoming only had two or three worth mention, while Massachussetts had three hundred and thirteen. What this meant is that every day I was writing maybe two thousand words plus research plus images of the flags in this thread, and over a month, that’s – well, that’s a book. If you read the whole flag thread, you read a very twittery book.

It’s also big enough that there really isn’t a convenient way to copy it into a document or translate to a webpage. I host the images I put on this blog on this blog – I don’t like the idea that another service going down will make the images fail, or that someone – hypothetically – can change what my blog is showing without my control over it. That means gathering my own versions of all of those flags – and there were almost eighteen hundred flags. Each blog post about them would be quite large, and a lot of those flag comments were just jokes based on a tiny number of extremely basic failings.

I’m not sure I’ve solved this problem yet. One possible solution is to just make the flag thread into an ebook, but that gets into a really fascinating complicated space.

See, anything posted on twitter is effectively transitory and there’s no expectation of financial remuneration. There’s a certain amount of leeway I get when I post a photo unsourced. I’m not sure, however, about the possible legal ramifications of the use of art owned by cities and states in a different country, especially when if I put the effort into making a good, well-formatted book, I’d be wanting to charge for it.

I mean I could, hypothetically crowdfund a book: Maybe just a book called Your Flags Are All Garbage, and pay an editor or legal department to work things out for me.

Still, for now, that’s an idea, rather than a plan. It’s a funny old thing, really. Creating things is hard, but then translating what we create to useful forms is hard, too.

Story Pile: The Saint (2017)

Aaaaah, they can’t all be hidden gems.

The Saint (2017) is certainly set up to be a hidden gem. I mean, hey, okay, c’mon, check out this breathless spiel. The Saint (2017) is a modern re-adaption of a long-running TV serial about a super cool super thief who flits around the world doing daring heists against extremely powerful evil people, and while he plays with lots of cool toys doing it, he still gives the money away to organisations like Doctors Without Borders and oh he has rad cute friends including a super-stylish lady on the wire who hacks things for him remotely and beats people up and she’s played by Eliza Dushku and there’s a gay black lady who’s on the trail of the villains and there’s a good conspiracy that our hero is the last member of and an evil conspiracy that he’s prepared to fight and it’s all slickly shot and it’s not like the 1990s movie that was bad, this one leans in hard to the stylish super-spy style, and Roger Moore has a guest spot in it,

and

it’s

almost good?

And then it’s very definitely not.

Continue Reading →3.5 Memories – Vileness

You know it’d be pretty easy to draw the conclusion, based on the way I talk about it, that I didn’t like 3.5 D&D. This couldn’t be further from the truth – I haven’t played the game in ten years and yet I still have all my books, still have character sheets and build articles and all sorts of interesting work I did. I wouldn’t write these articles about 3rd edition books and mechanics where I reminisce about how the things I did – silly as they were – were still cool. I liked 3.5.

But gosh did it make it hard.

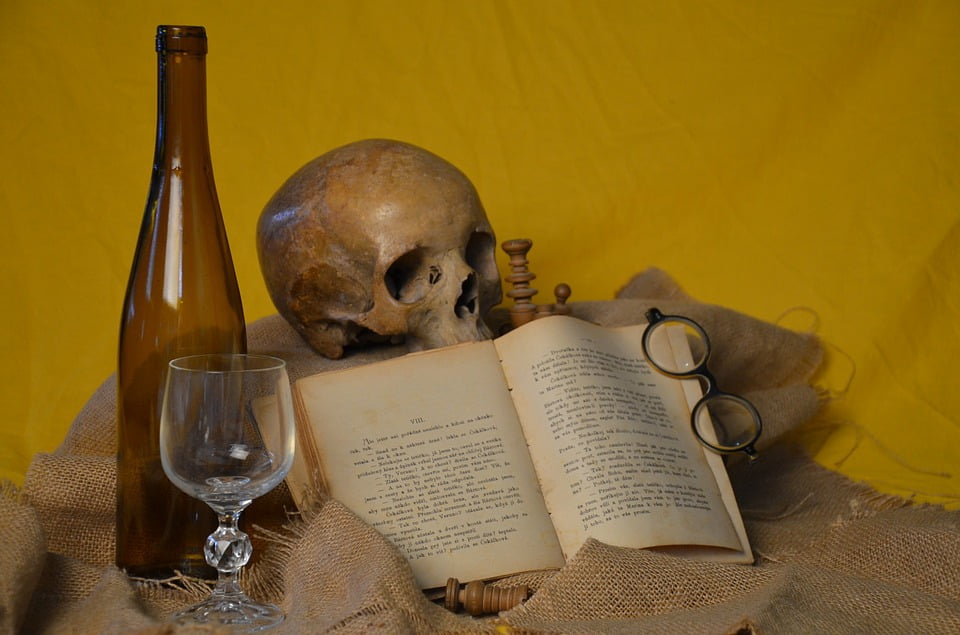

The Dragon As State

It seems only fitting that with Game of Thrones finally spilled out and bleeding its guts on the floor of the greater media community, that I trot this take out that is simultaneously extremely uncomfortable and also right.

Dragons, in most fantasy fiction, are governments.

I’ve talked in the past about how fantasy isn’t about some actual historical place (indeed, no media is) but rather is about how we exist in our world, today and now. Werewolves are things like fear of the stranger, the owlbear is the threat of the unknown in the dark of the woods, witches are a fear of women, selkies are a fear of women, the gorgon is a fear of women and you know it’s possible a lot of our myths that have survived haven’t been very cool about women now I say it out loud. Still, with the idea of these monsters representing things that we can then create and ensoul as entitites that we can interact with, that we can talk to and maybe fight, that is, in most narrative, the job of the monster.

The Dragons in Love of Varna, Bulgaria

And the Dragon, as a monster, is big. Dragons aren’t just materially big, but they affect the world around them in a really big way. They change the way food is made where people give up some of their herds to the dragon. They change where people go and move, they make them move in groups or stick together, they make people set up highways and guards and build castles and keeps, and try to live their lives in the hope of avoiding the attention of the dragon. People don’t forget it’s there, and they are aware of its influence, and they know they do things just in case of it.

Sometimes, the dragon is good, and thanks to that, there are things like cures to terrible disease, and safety from dangerous armies and the people just accept a few missing cows as the nature of their life, and it’s okay. Sometimes, the dragon is bad, and there are times when it comes out to destroy things for no good reason.

We even call them tyrants.

There are even things like kobold cults and draconic servants around some – people who exist to handle the management of things for the dragon’s whims! There are people who live in service of the dragon like beaurocrats and police and seneschals and they too, are referred to like creatures in a government.

Then you should look at the dragon in terms of who kills them. What your story can see as a way that a dragon dies. Does a dragon ever get beaten to death by all the oppressed peasants? No. It’s too big, too powerful. The actions of one ordinary person are too little. There is nothing one person can do, and a thousand nothings add up to nothing.

But a dragon can be felled, by a knight, or a cleric, or a barbarian or a priest. A dragon can be swayed by a lone hero. A dragon can be defeated by a lone individual or small group of those individuals, who represent, to the reader, a right way to kill a dragon. There are even small dragons, individual dragons, who don’t want that power and that scale and that scope, and who define themselves by being one creature, not a dragon like those, a thing of the same stuff but not the same type.

It’s interesting, almost like little anarchist cells, really. When I talked about the Tiefling as an avatar for the beneficiary of historical colonialism, there is a cousin to that idea; the notion of the dragonkin, the person-dragon, the dragon that cannot rule – and that be the individual who can look at the power concentrated in bad governments and say, they know, they know that whatever this is, it can end, and needs to end, and are willing to destroy the ways they are priviliged to do it.

A dragon is a government you can fight, or kill, or fuck, in the right way. The dragonborn and dragonkin? Antifa.

And maybe there need to be more stories of dragons torn to pieces with scythes and thresher’s sticks.

Game Pile: A Slow Swindle, Part 1(?)

Playing the Monster

I’m not going to buy a Vampire book to find out what their dumb explanation is for this, okay?

Every now and again, someone playing a White Wolf RPG gets some attention on internet because of some bad decision of a player, usually, or a storyteller, just as usually, and the question is always ‘here’s some really supremely fucked up thing that I and my friends sat around doing in our pretendy-fun-time game, and someone thought it was fucked up, am I good?’

There’s a lot of different conversations that spin off this, like the shrapnel of a thrown firecracker, and some of those conversations are good, like ‘how do I communicate better with my group,’ or ‘how do we relate to the media that we create in play,’ but there are also a lot of really silly conversations, including ‘why do these people play that bad game, they should play my much better game,’ or ‘doesn’t this show how everyone who likes that game is a bad person.’

One big roadblock to the conversation that comes up, often, is the all-purpose tried-and-true, worked-on-the-Satanic-Panic why-doesn’t-it-work-now response is that in Vampire (and it’s so often Vampire, but hey, sometimes it’s Werewolf, but, these days, certainly lately, it’s Vampire), you are playing the monsters, and that’s that, they say, folding their arms and smugly sitting back.

The correct response to that is ‘so?’

Playing a monster isn’t hard. It’s not even that interesting. What these games want to do, usually, in their best forms, is try to get you, the player into a mental space where you can appreciate the framework of a monstrous creature. Recently, though, that seems to be biased towards the idea that a vampire is a thing that by necessity must always be evil – that there is no way for a vampire to be a valid member of human society. This is a pretty novel idea, though, because it asks the question, why?

Now, one thing here is that the World of Darkness is a universe which has a sort of fundamental moral footing, so if the story wants to say ‘this thing is evil,’ then okay, it’s evil, just there you go, all Divinely Decreed. But these aren’t games that want to try and express that, they kinda balk at the idea of having their morality be as basic as Dungeons & Dragons (even though it pretty much is). Instead they start talking about moral justifications for power in their universe, or what makes Vampires ‘bad,’ and what ‘evil’ is in this universe.

Essentially, these arguments about what makes the Vampires monstrous is ‘they hurt people.’ Not just ‘the vampires that are like, Nazis, hurt people’ but just being a vampire hurts people. Your vampire can only exist as a parasite and that means they literally can never morally exist in the universe. This puts the Vampire world’s moral framework as kinda hilariously puritanical: There can be no moral application of violence, even in the opposition of the violent. Intention is not just corrupt, but your intentions can be corrupted by your nature. This extends throughout the universe – Vampire hunters are seen as corrupted by their pursuit of stopping Vampires. It’s a world where the Abyss doesn’t just look into you, but the only moral action that doesn’t lead to corruption is to lay down and just fucking die.

It is afraid of violence, in the most pearl-clutching way, and tries to enforce its fears with its rules about the world, then enforces those rules with lore about feeding a cosmic abyss.

You may be ‘playing the monsters’ but you’re playing monsters in a world so profoundly backassward that being a monster is meaningless.

Seems That Game of Thrones Is Bad, Huh?

That Game of Thrones, eh?

Now it might be that someone in the past, once, said that by definition The Game of Thrones was doomed to have an unsatisfying ending, and that someone may have said that the whole story was something like, you know, a narrative lootbox and then Game of Thrones ended and its ending was bad, and the ending being bad resulted in a giant pile of people suddenly going ‘hey, has this… sucked for years?’ and suddenly everyone is arguing about when the whole affair went sour, when this prestige TV show worth millions of dollars they’d sunk their life and fandom into might be bad and they should have known it ahead of time.

The really interesting thing to come out of it, though, is the understanding that part of what made the ending of Game of Thrones bad was not, as I once asserted, that they had no idea where they were going, but that they had an absolute, clear, definite ending, and that meant that accomplishing events in the final season was a matter of ticking things off a list, in order to force the time they had to fit the sequence of events they had to show.

And you know what, that’s fair. Maybe it wasn’t a lack of a plan, the problem was too much of a plan. Or maybe it was an inability to contain what they were making along the lines of that plan. Or maybe it was people’s fault, for being too into it, and it got too popular, forcing those poor creators to ruin it. Or maybe there was a conspiracy. I honestly don’t know, or really care. I don’t think there are lessons from Game of Thrones that are specifically really applicable to you and your creative work, beyond maybe, that if you put a lot of sexual assault in your work, people are going to ask exactly what the fuck is wrong with you, and getting defensive just makes everyone start to draw conclusions about that answer.

That’s the thing. It’s too big a work. And based on watching video of the actors preparing for the show, and the special effects crew and the prop makers and the armour fitters and all that stuff, I think it’s reasonable to say that on average everyone who showed up to make that series did a great job. But not everyone’s effort has an equal impact on the outcome.

I look forward to this future where Game of Thrones dissection becomes our personal rite, where everyone has their opinion about what in this series failed, why it failed, how the real problem the series had was this, or that, or the other. It’s great. It’s wonderful to see this practice turned widely mainstream. Hi, everyone else, this is what anime nerds have been doing since forever.

Turns out the real Iron Throne was the friends we made along the way!

July Shirt: UwUnionise!

Don’t let it be said I don’t listen to my twitter followers. I tweeted this, someone wanted it on a shirt, and here we are.

Here’s the design:

And here the design is on our friendly gormless supposedly unisex Redbubble model:

And here’s the design being modelled by the Teepublic ghost:

This design is available on a host of shirts and styles. If you like the look, I can see about making the individual badges into stickers.

Story Pile: Geobreeders

I’ve been talking about anime a lot this year. And because I’m an older anime fan, a fan boy, as it were,it’s easy to reach back into a history that’s older than some of you and point to these old classic works, things that are important and influential and you should feel ashamed you don’t know about them, I guess, if my expectation of generalised anxiety and imposter syndrome is usefully applicable.

Partly, this is because I’m a believer in the idea that remembering art is enough to make it meaningful, and there isn’t really a bottom threshold on ‘worth talking about.’ I watched a lot of garbage back then, some of which I found it fun to ridicule but some of which wasn’t good in a very boring, tedious way.

The Game Pitch

Everyone has their own silly loves. Everyone has things they like doing that don’t make sense to anyone else, right? You know there’s someone who likes refining or commenting their code or someone who enjoys doing reference citations or someone who likes sorting a library of books. All that stuff. Right?

Well, something I love, a lot, is pitching games.

Not the big, stand-in-front-of-investors, white-board and flop-sweat pitching. That doesn’t bother me but I rarely find it fun. That’s actually really challenging because you’re in a live-fire exercise trying to find the frame of reference for your audience and want to construct a kind of language gear that you can use to connect to them and turn the wheel of their mind. That’s hard, that’s really hard, and the fun that you get out of it is a very different beast.

No no no – what I mean is pitching a game to my players.

When you’re to start a campaign of a roleplaying game, it helps to have an idea of where you’re going, how the plot might work out, the kind of things – in a general sense! – you’re going to be dealing with. You don’t want to plan it to death, dear god, no – but you want to have an idea of your tone. You want your style. Do a little conversation with your players, feel out what they’re into, feel out what you’re into, and commit something onto paper to be the groundwork for them to make their characters, and what you have there is the basics of your game pitch.

Game pitches are really fun because they’re high concept views on stories but also they leave one of the most important parts of a story completely blank: you have no idea who the protagonists are. This means you get to shape the kind of characters someone might want to make, but you also don’t know what you’re going to get. At the same time, because you get to lay down rules, you also get to tell people the kinds of characters they should bring, without necessarily defining anything too clearly. It’s great! It’s this wonderful little potential bubble of stuff.

And then you get to wrap that up in some mood writing, something to give people an idea of how you want them to feel going in. You might lead with some fatalistic poetry or a quote from a scholar, or an excerpt of relevant history, or maybe you share an account from some character the story meets. Maybe you’ll show a scene of something, an actual snippet of history. Or maybe, you’ll lead with a short, bitter phrase, something the characters may already know, may already repeat to one another, bitterly.

I keep around a bunch of these pitches in my books and archives. The house rules, written down, the character creation rules, the guide to things like ‘we want characters who are heroic’ or ‘we want characters who are connected to this organisation,’ or ‘one member of the group has this royaly title.’ One came I ran, Border Guard, the brief opened with the phrase:

We’re not the best

We’re not the brightest

We’re not all we can be

We’re just here.

One of the players who played in that game turned to me once, about the sleep he had lost taking care of one of his parents through a medical rough patch. About how he hadn’t signed up for that difficult task. And he said it back to me, and then added, he couldn’t remember where he heard it.

I love creating game briefs.

They’re so much fun~.

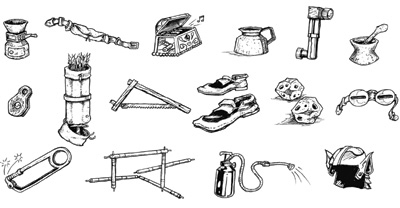

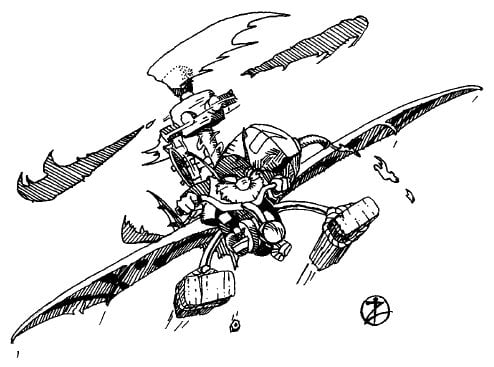

Starting Making, Concept 1: Halls In The Mark

Okay, okay, I’ve talked about making games, and I’ve tried to talk about getting started, but I know that just because I’ve mentioned something once doesn’t mean it’s always there for people to find. There is a river of content, and restating things in different ways is worth doing, because it means you are more likely to potentially get a hook

I’ve talked about how to view those things, but I haven’t done a lot as far as showing the process, so today I’m going to show you how I approach this process, by taking an idea I have and showing you how I arrive at decisions of what to do after I have the idea.Continue Reading →

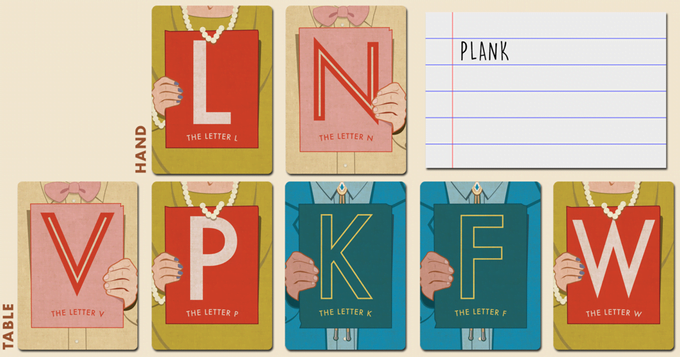

Game Pile: Handsome

I’ve gone back and forth on whether or not to talk about this game, because I feel that it’s almost like a big tweet.

Handsome is a Button Shy wallet game. Sometimes we get these game terms where you might be a bit lost by what we mean, like a hidden identity or bluffing or secret identity or whatever, but this one’s about how big the game is. A wallet game is a game you can stick in your wallet. It’s tiny, it’s so small you can carry it around with you everywhere. This is something Button Shy do really well, with regular kickstarters for very small games.

I keep a copy of Sprawlopolis in my bag all the time now – it just lives in the little section of things I never have to check because odds are I’ll always want one, and it’s proven to be a wonderful tool for introducing people to my particular genre of game.

Anyway, Handsome is the next game by them and it’s almost a kind of roll-and write, a game that scales up deftly to any number of players.

Handsome is a card game where there are community cards, your own cards, and you’re trying to build words out of them. It’s elegant in its scoring and its system – you get as many vowels as you want, but then you have to make as long a words as you can, involving as many of the different suits of letter on the table, and that’s it. That’s the whole cycle. You see who gets the most points, then you can play to more letters or not.

There’s no intense tension about the word play here. You don’t need to do a lot of interconnected play, there’s no board, it’s this tiny little thing, and there’s not a lot of rules to learn. It’s very pure little game, and that’s why I feel like praising it is almost just… y’know. A tweet.

Hey, it’s another Button Shy game. I bought it, because I thought it looked good, and I played it, and it’s great. There, tweet sized greatness.

I think a real measure of a game’s quality is how quickly after playing with you, someone goes and gets their own copy. I don’t know about you but I’ve always had a tense relationship with games, with my friends, because even when I’m having fun and enjoying the experience, there’s a part of my brain that’s still the damaged little church kid knowing that they’re putting up with my weird little interest as an act of kindness and the second I’m out of sight, they’ll breathe a long sigh of relief.

I showed this game to my sister on a Saturday.

That monday, she bought the Print-And-Play and was playing it with her class.

I Like: Dave And Jeb Aren’t Mean

I grew up in a bubble of what I refer to as ‘Christian Replacement Media,’ which is this space full of movies and tv shows where the budgets are low, the talent pool is shallow, and there’s a host of very natural and normal things that the shows can’t depict, because it’s a moral evil to have a character swear. It’s not enough that the work shows people who swear as bad, or that swearing be rare, it’s that swearing at all is bad.

These are stories that try to do moral panic and endangerment and horror of the other by such things as ‘someone grabbed my wrist’ or ‘a black person said hey unprompted, with an accent,’ and the romances in them appear at the last instant, as the boy we’re followed meets a girl and she smiles at him and the music swells, implying they are absolutely going to be together forever.

Christian Replacement Media is a lot of things. Mostly it’s surreal, a sort of heightened reality where the story winks at you and says You know how this is meant to work, meaning they don’t have to show you the things they’re hinting at. It’s media by summary.

Anyway, what that means is that when I discovered Dave and Jeb Aren’t Mean, a podcast about two normal humans with normal frames of reference reviewing the movies of the Hallmark network, I was hooked.

Hallmark make movies that are not Christian Replacement Media, but are designed to form part of that space, the spackle of the entertainment media. You know, you don’t necessarily want to appeal only to those consumers, but if your work fits in their landscape, there’s a large market of the no-swears no-offensive-content as-few-black-people-as-possible media.

These stories are weird and unnatural, and this podcast makes them a hilarious part of the landscape that I heartily recommend you check it the heck out.

What Can Hide In Your World?

Watching Hannibal – which is bad, by the way – I was reminded of an old conversation about hiding things in your setting. The same idea is root to the narrative of Brightburn, and in turn tangled around the root of the Marvel Cinematic Universe. Still, it’s a question that’s important to the world building in your games, because it shows what your world has room for.

In the Marvel Cinematic Universe, superheroes can ‘lay low,’ and be more or less well hidden, but once they start ‘doing stuff’ of any scale it’s pretty likely they get found. This is because that world has a organisation that makes a positive showing of constantly looking for these people (‘in some way’) and the narrative kind of doesn’t ask any questions about what that means. Now, in this world, the point of this is to bring superheroes into attention and get past the boring bits of an origin story – just have the Shield folk turn up a new hero, and get involved in the story at an interesting bit after all the tedious bits are over. This is to say that in the Marvel Cinematic Universe, there’s literally a heroic surveillance state that not only does things you want them to do (speed up superhero stories) but makes monitoring everything in the world seem cool and doable.

In Hannibal, there’s somehow enough means for multiple serial killers with lurid, vividly horrible modus operandi to spring up in one area over the course of a few weeks, with their activities overlapping, and the department of the FBI that was set to the task of dealing with them was like, five people. Now, that seems weird to me, but that’s what this setting needs – and I mean, if Hannibal Lecter is a wealthy millionaire then it’s kind of fine, I guess, that he can just murder people with impunity, but if that was the case why would he bother being so careful about his identity? The story already has a monster – Mason Verger – whose money makes him immune to punishment, so like, what does it matter that these things are hidden? How are these bodies being moved around, these elaborate tableaus being only discussed by one sleazy blog?

In Brightburn, the question is ‘how likely is a meteorite landing to be noticed in the year of our lord 2010,’ which I guess leans on the wall of what’s believable, but also then builds a story about ‘how creepy and invasive can a single kid be without anyone noticing it, and how likely is that to be de-escalated.’ That’s interesting.

(Brightburn doesn’t do anything interesting with it).

The thing is, in each of these cases, these are worlds that are meant to be like ours – some even give a specific date! In our world, it’s hard to maintain fictions about big events, because we have recording devices everywhere, a sort of sousveillance state.

In a fantasy setting, we don’t tend to have rapid communication, but we do tend to have a reasonably modern vision of trade. It’s one of the funnier things I’ve noticed in most fantasy RPG settings – there’s a vision of commercial trade that’s generally a lot further along than the technology and societies imply. I actually really like Erik’s term of Castlepunk for this – you’re not gunning to represent a real pre-rennaisance world, you’re just jamming the cool looking bits of it together and asserting that it would make sense, so relax. The point is, people are moving, and goods are moving, and people are buying and selling things in a meaningful way. That means they’re talking.

Something to consider for your D&D settings, then, to think about in terms of how well they know the places next door. Every place you go probably knows two or three things about the place one town over, and they probably know the biggest place in the region. Think about it as an exercise; three individual ideas about each adjacent place, and three ideas about the capital. You can even treat these lists as traits of the place.

For your town, jot down say, five traits. People in the town know five of them, people one town away maybe know three, and people another town over know one. This is a really simple, dirty trick for starting out your worldbuilding, but it does the job of representing the way information moves around from place to place.

Turning The Gear Of Surprise Mechanics

The play of an actor, the play of a gear. When you hear a phrase enough it can dull out, lose its meaning, and in academia, some sentences are constructed so that they convey a host of ideas in a small space and allow for branching discussions. The medium is the message, and the many ways you can expand that sentence, to show different things that McLuahn said in other places, in other times, because they were all built off that idea.

Hold onto that, we’ll need it later.

Story Pile: Snow White and the Huntsman

Back in February, you may remember – because you read everything I write, right? – that I tried to make a bunch of articles about smooch media, and one of my choices was to try and focus on romantic movies that were doing something interesting and cool and not just another Two Extremely Hot Movie Stars Awkwardly Bump Into Each Other In A Predictable Way.

At first I found there was this seam of ‘romance’ movies that were clearly made for men – my iconic example is This Is War, a movie about two super-spies that compete for a hot girl and an action movie breaks out while they’re doing super creepy abuse of surveillance state technology in order to get emotional upskirts of this girl. Now, I felt in my heart that I’d really like an action movie romance if the romance was just between two people of comparative levels of attractiveness.

That’s another thing. Dudes in romance stories are either tremendous people with the emotional capacity of a grape, or they’re potatoes that get girls because they’re in a designated story slot. There are a lot of movies about ugly dudes getting beautiful women to fall in love with them – things in the mould of Knocked Up or, well, any where the central male actor is known primarily as a comedian and not as a ‘leading man.’

I was honestly really hopeful then, when I popped open Snow White And the Huntsman.

And what I got was an amazing sequence of failures.

Spoilers ahead.

A Dead Week

I simplify talking about this blog as “I write something every day.” And I do that, generally speaking, but it’s not like what I write, every day, goes into this blog. For example, in May and June, I did a flag thread on twitter, which was a huge amount of research and work, and a lot of that work was writing work. That all got put onto twitter, and that work didn’t show up on the blog here.

Now, there was something that went up every day, because I made a backlog on my blog. I’m happy with that. This week – which is back in June – I have been sick. And like, surprisingly sick. One part of that has been difficulty sleeping, and difficulty composing complex thoughts. Bonus: This is the time I’m revising a most important part of my next stage of my PhD, which means if I have 12 points of brain-think each day, those 12 points are going to get used on my PhD, sorry, and that means nothing much else happens.

I’ve been trying to prioritise and one thing that that prioritising means is that at the end of the day, if I need an extra six hours of sleep, those extra six hours are going to happen before another blog post. Which does mean that now, as I start to feel better (he says, hoping), I need to climb back in to the backlog.

It’s easy to get the impression from me that I’m this endlessly productive super-beast, which I’m just not. I have my setbacks too. I’ve just set things up to make these things less obvious.

I know some of you are just starting out working on writing. It can be really scary to look at what other people are doing, and think they’ve always got on top of it, they’re always fine. I’m not fine right now. I’m not producing as much or as easily as I want to be. And now I am recovering.

Hunter’s Dreams – Handling ‘Race,’ Part 2

This is more work on Hunter’s Dream, a 4th Edition D&D-compatible mod made to enable a Bloodborne style of game, where players take on the role of hunters, who have to first research their prey before going out to the tactical combat stage of things where players get to have cool fights with werewolves and whatnot.

Last time I outlined some of the problems with ‘race’ as she is treated in the game of Dungeons and Dragons 4th Edition, the challenges of making settings through the ‘race’ option, and the potential, unconnected legal concerns with how to treat races so as to not invalidate the rules of making 4th edition D&D content.

Those are our parameters, the problems we need to consider. Now let’s talk about what I’m going to choose to overcome this.

Game Pile: Yoshi’s Crafted World

Yoshi’s Crafted World is, well, it’s a Yoshi game. It’s a Yoshi game, made by Nintendo, and that means that there’s a part of my brain with a groove worn into it where this game locks a strange mechanism that means that I’m constantly in mind Yoshi’s Island, one of the best console games I’ve ever played. As I write this, I’m hearing the music from the game – but not Crafted World, the music from Yoshi’s Island. It’s part of me.

I’ve talked in the past about how much impact Yoshi’s Island had on me as a player, but I also know that being A Yoshi’s Island isn’t enough to pollute my common sense and leave me unable to rationally examine a game, because the game Yoshi’s Island DS annoyed me a great deal for Not Being As Good as Yoshi’s Island.

Any given Yoshi’s Island game is going to be judged then in terms of how well it delivers on the platonic ideal of the first Yoshi’s Island game that I love the most. Yoshi’s Story gave more visual depth and less fluid flow. Yoshi’s Island DS offered larger levels but they weren’t as good.

Hunter’s Dreams – Handling ‘Race,’ Part 1

This is more work on Hunter’s Dream, a 4th Edition D&D-compatible mod made to enable a Bloodborne style of game, where players take on the role of hunters, who have to first research their prey before going out to the tactical combat stage of things where players get to have cool fights with werewolves and whatnot.

This time, he said, in the tone of voice of a breathless white boy who has just completed his first college course on the topic, I want to talk to you about race.

Race in D&D is a fraught topic, so going ahead, we’re going to talk about some things that are racist, and we’re going to talk about trope space and fantasy novels, and how those things are going to be racist too. Just be braced. This is before we talk about the choices I’m making in Hunter’s Dream as much as it is about me thinking my way through the problem and whether or not it’s good to address it in this.

Defining Mastery Depth

Hey, let’s talk about things for talking about games! And sure, it’s old hat to me, but if I use it and you don’t know what I mean, I look like a stupid asshole talking over your head, and it’s important to remember everyone learns a concept somewhere!

I want to talk about Mastery Depth, a term I used when talking about Century: Golem, then realised I may have never mentioned it anywhere before. I mentioned it offhandedly, but never really sat down and wrote out what I mean when I describe it in games, or what it’s good for or what it’s not.

Here’s the concept, then: Mastery. The ‘put it in a single sentence’ version of Mastery looks like this: Mastery is the way the game is affected by having already come to understand the game.

That’s a small sentence, it’s reasonably simple words, and it’s also a little confusing. I’ll try to explain it better. For pretty much every game, previous experience playing the game makes the game easier to play. Sometimes that’s just a matter of learning the rules more thoroughly, so you don’t need to look things up. Sometimes it’s about knowing what you should prioritise in the game, after the rules present them to you as a big wave of equal stuff.

Mastery depth is a way to look at a game in terms of how much of what a game does that rewards players with more or less mastery. Is there a game you can think of where there’s a particular dangerous situation that can come up and you need to know how to recognise it? What about the way we see Chess, a game with a variety of ‘openings’ that require learning a new language to understand? Mastery is how you recognise those things. A game that rewards mastery often rewards playing with mastery – games like Dungeons and Dragons are mind-blowingly complex, but as you master them you learn how to stop caring about unimportant details, and learn ways to build the game to get the outcomes you want.

A lot of games get called ‘bad’ because they lack mastery depth, and some are ‘bad’ because their mastery depth has a hard limit. Connect Four and Tic-Tac-Toe are games that once you understand them enough are solved, and the person with sufficient mastery knows the way the game will go and wins it. By comparison, though, there are some games where it’s hard to tell different levels of mastery – you can look to the intricate and complex development of Magic: The Gathering, where asking a computer to calculate ‘best plays’ in any given situation is brain-explodingly difficult.

I think about this because one type of game I’m trying to avoid creating and sharing with my niblings is games where I, a grown adult with time to focus and a better constructed memory and a lot of experience, am just always going to beat them because they are kids. This has meant I’ve been delighted by some games I normally used to think of poorly – I bought King of Tokyo and have found it an exceptional game in its class, for example.

Bear in mind what players need to know, how much they have to play, and if your game needs mastery or rewards mastery, and if you’re okay with that. Mastery is fun! I love games with a lot of mastery depth… but I’m also learning to love the games that are a bit less likely to reward you for a long-term plan.

City of Heroes and the Clamps!

In case you weren’t aware, City of Heroes is (as I write this) back (kinda?), and with it comes the return of forums. These are not places I’ve been going, because these forums are full of people whose opinions I do not much respect, and what’s more, now they don’t have an actually gatekept developer space, so instead we have a group of very entitled people wanting to talk about making development changes to a game they’re very confident they know how to ‘fix.’

Most of the time, these people don’t know what they’re doing or talking about, and don’t know how hard or easy what they’re suggesting would be to implement that. One suggestion I’ve heard is about something someone sees as contentious, is getting rid of the CLAMP.

For those not aware of very old development lingo, the Clamp is a term used in City of Heroes development for the to-hit formula. The basic idea was that any time you tried to attack something, the game would do some math and you’d see whether or not you successfully hit your opponent. No matter what you did to your chance to hit, you’d always have a 5% chance to miss, and that’s the ‘Clamp’ of the discussion.

It’s a pretty silly thing to get angry about because you might be familiar with this as a basic critical miss mechanic. This mechanic is common to a lot of tabletop games, and really, common to a lot of videogames that are just so gauche as to not tell you they’re doing math when they try and shoot you.

I’m not going to get into an argument with this person about why the Clamp should be around, or why their suggestion to get rid of it in a game that otherwise works fine is nonsense, but it did make me think about addressing why you even want a critical failure system in a game at all.

The thing this Clamp did for City of Heroes in combat is what it does in all other games that use this system for combat: It stops combat from ever reaching a place of being potentially identical. When you throw a fireball into a group that it will probably kill, the fact you can’t be sure who will survive is important to make sure that your turn has some variance in it. In City of Heroes, where you’re making hundreds of attack rolls over sequences of seconds-long combats in minutes-long missions, these little bumps of the unreliability mean that you’re still making decisions and choices while you play, because you can’t be sure who will run and when.

Now, that’s not to say critical misses or absolute failures are a good thing in all games. One of my favourite designs in Blades in the Dark is because in that game, ‘success’ seems very attainable – it’s usually something like a 1/2, with some complications, and any extra dice make it more likely you’ll get something like a success. The pool of dice you roll is never very big, and that means you’re likely to get hit with random variance and then that failure becomes a thing.

Similarly, you can check how the kinds of times you want to make those checks. In City of Heroes, these rolls to see if you succeed or not are made when you want to attack something, but not when you’re seeing whether or not you successfully craft and object you want for your build. It’s not that this is a game where you can always fail, it’s a game where you want to represent combat as being about an interesting experience, whereas crafting is more about just getting what you want when you pay for it.

These systems are not used without a reason, and the reason to use them is challenging to explain to players. Players may think they want the game to never let them miss, but if you give them that game, they may find it more boring, less interesting but never know exactly why. It’s a really dark art, tuning player experience, and there’s going to be things they don’t like that they don’t know why they don’t like.

Story Pile: Solo

Disclosure: Someone I know worked for one of the companies that got Solo made. I don’t know the precise details and I don’t want to pry, but there you go. I don’t imagine they care that much if I think the movie is good or bad, and they haven’t spoken to me about the movie’s quality.

With that in mind, some bonafides up front: I am the Doesn’t Really Think That Much Of Star Wars guy. Not a ‘they were better when I was a kid’ guy or the ‘well this stuff lacks the depth of cinema veritate’ guy, but just someone who has for some reason or another never had that much of a high opinion of Star Wars as a franchise. I have had my fair share of Star Wars media – mostly in the form of videogames, books and my fill of watching the movies – so I am not ignorant of it, I just don’t really think it’s very interesting. It’s a bit like Monopoly – I understand that it has a deep cultural impact and lots of people are very familiar with it but I just don’t think it’s particularly good.

I guess the easiest way to explain what kind of Star Wars fan I am is that I think 90% of the movies are boring and the remaining 10% is all full of Ewoks.

Anyway, Solo is a movie seen as ‘controversial’ because Star Wars fans are just the worst kind of joke. There’s just the silliest kind of swirl of ridiculousness around this movie’s box office sales, conspiracy theories that are one step removed from saying ‘the Jews don’t want a movie about a strong white man to succeed!’ and there’s a lot of noise. Since it seemed Star Wars fans didn’t like it, I thought hey, maybe I should check it out. Maybe I’d like it, if it wasn’t something that appealed to the kind of people who thought Star Wars was good. Right? There’s a logic there, surely?

Anyway, I kind of love this awful movie, but I also kind of hate this great movie.

Goldshire Inn Ethnography

Before there was photography, there was heliography. It was from around the 1820s, and to make a picture with heliography you needed to get a big funnel-shaped distorted mirror to capture sunlight and direct it through a glass lens and onto a plate of chemicals and it created an image. Things had to hold very still while the sunlight ‘etched’ onto the chemicals, and it was pretty quickly outmoded by photography.

The heliograph was used in its narrow window of time in the – haha – sun, to take pictures of naked ladies, who came in and held poses long enough to get shadowy silhouettes made.

In Game Research Methods, Lankoski and Bjork explain a bunch of different methods for studying games academically. It addresses techniques that are unique to games, ways that games fit in with existing research tools, and challenges that games have that people unfamiliar with them won’t necessarily consider. This is where I first got the idea of Stimulated Recall, where recording yourself playing a game, then watching that playback is a chance to talk about and experience your mental state and give a more accurate accounting of the play experience.

This book also includes a really interesting chapter about understanding the ramifications of ethical disclosure in digital spaces as it relates to subjects (people) and their ability to share information. That’s a big sentence but it’s basically a finding from a researcher who was studying people ERPing in WoW.

Now I’m not going to infantalise you and pretend you have no idea what those acronyms are. For the sake of completion, though, ‘WoW’ refers to World of Warcraft, and ERP refers to ‘Erotic Roleplay.’ It’s got a lot of possible terms but the basic idea is using text roleplay in a game’s shared space to roleplay out sex.

Now, some people react to this discovery with incredulity, which I find kinda tiresome, but yeah, if you have literally never heard of this: People do this. In fact, people doing this is as old as the internet itself. In fact, back in the day, before the internet, people used to write dirty letters to one another, to make up a sexy narrative. Like, written with hand. There even used to be a whole range of clever acronyms for those dirty letters, a hidden language that was designed to convey information to the insiders and keep the communication fast and fluid.

A lot of those letters you see people reading in World War 1 re-enactment dramas, a tearful moment as the music swells and you, the audience, reflect on this humanising moment as this soldier is connected to their home country and given a reason to feel just for this moment not here in this filthy trench?

Those letters were really dirty.

Anyway the chapter is interesting and includes a lot of self-examination from the researcher, who realised that their work was not just about examining the interactions of objects in a space, it was the behaviour of people, and reading logs of people boning meant getting insights not just into the practice academically, but also the way people feel about themselves, and one another. About the meaning of our virtual bodies, the bodies we use to express ourselves, and it’s all very good reading and it’s very interesting about designing your data capture so it takes into account the ethical needs of intimate places that players create. It’s really interesting.

It’s also four years old, and built on existing research into ERP. Which is why I know those things about those filthy letters, and about the heliography of naked ladies. People make stories with one another, and people use technology, and one of the most common things people use that technology for, and make those stories about, is, well, sex. Sometimes weird sex, sometimes chaste sex, sometimes circling around not wanting to call it sex.

I guess I bring this up because I still see people using ‘people ERP on the internet’ as a punchline. Sometimes a website like Polygon or Waypoint will talk about it and in a very hamfisted way I get to watch as other people slap at the topic with a lack of nuance that speaks of embarassment.

People do this. It’s not weird. Try and have some chill about other people’s fun.

Owlbear Traps

In the past I have remarked upon the idea of Dungeons and Dragons 4th edition’s quality as it being a game that lacked ‘bear traps.’ This is just a basic metaphor, you know, comparisons between a thing that could hurt you hiding in an undergrowth, that you might never realise was there until after it hurt you? It wasn’t ever meant to be a genuine game design term, not something I’d use in serious discussions.

Yeah except now I’m using it and I need to nail down that to make sure people might know what I mean, and I’m going to be very specific here. I’m talking about Dungeons and Dragons 3rd Edition as examples of game design, and I’m talking about the overall philosophy of the game.

Dungeons and Dragons 3rd Edition did not mind or care if you had a bad time that was the game’s fault.

I’ve spoken in the past about the sorcerer and the wizard; the tension that lay between two classes that were very similar, with one just being markedly worse than the other, and the competitive design mindset between them. I’ve also spoken in the past about how there’s this class, the Druid, where they have a class feature that’s about 80% of everything that a Fighter is, and how over time, that class feature improves faster than the fighter, resulting in overtaking in the mid-game.

The big issue of 3.5 class balance is that melee combat was, just in general, not as good as magic. Ranged combat wasn’t that good either, but it could be made to compete with magic, mostly through the use of magic. The best archers in the game were inevitably spellcasters using magic to compensate for what the fighters and rangers were given, and still had their spellcasting besides.

This is something of the philosophy of this game, where it wants it to be possible to mess up building or playing your character. It’s a way to represent ‘being good’ at Dungeons and Dragons. Which is an interesting idea, and one that I kind of want to support, on one level. I think games are better when they’re made as sequences of interesting decisions; deck-building in Magic: The Gathering is an interesting decision, and that doesn’t make the game play experience of it that different. Heck, you could view a draft, then a deck build, then the matches of Magic: The Gathering as multiple different games, with all sorts of interesting decisions along the way.

The problem is that an evening of drafting for Magic: The Gathering is maybe four hours and you’re done while building a Dungeons and Dragons character in 3.5 required an enormous investment in time because you could only level them up as the game progressed.

It’s also gatekeeping: The game wants to give you the means to screw up at it, because the idea is that doing well or making smart choices is more satisfying and rewarding. Except your character, their feats and their powers are not a small choice; they grow over time based on your experience playing a game and may take months or years to come to fruition. You might need to read dozens of books to get a handle on how a character really works – the full breadth of a character may be dozens of books, some of which are totally unrelated.

This game presented you with choices of varying difficulty, but you needed enormous context to know how those choices worked. And you had to master the system to ever appreciate how bad some of the choices were.

And thus we have an owlbear trap: A way in which Dungeons and Dragons 3.5’s design philosophy prioritised servicing an enfranchised, qualified group of players in order to make it tangibly more desireable to do the things those players liked. Or to simplify: An owlbear trap is when you make it possible for new players to fail, just because they’re new.

Game Pile: Century Golem

First up, if you like light economic euro-style games, where nobody is actually trying to attack one another, and where the goal you’re building towards is just something nice and wholesome, I wholeheartedly recommend Century: Golem Edition.

It’s a great game, particularly because it doesn’t have tons of mastery depth to it; you’re not going to have an advantage over the player who plays it three times when you’ve played it twenty times. Everything you can do in this game, you learn how to do in the first turn, and after that, it’s just a matter of reacting well to what’s happening in front of you.

Players getting ahead put themselves behind, and even the last card flipped can change the fate of the game without feeling unearned. It is a game so quick that you’re rarely left waiting for your turn, but it’s still a game where it’s worth having a think about what you want to do.

Century: Golem Edition is an excellent economic trading game, and if you want this kind of game, this is a fantastic example of it. It is a fantastic example of the kinds of things this hobby can do.

It is also beautiful for its mechanics, and its base assumptions.

Gnome Names

Hey, you know Gnome names? Popwhistle, Grindgear, Bombfuse, Fizzlewist.

Why are they like that, you think?

In almost any setting I’ve seen with Gnomes, they tend to follow this kind of rule. Sometimes the setting is a little more Tolkeiny and the Gnomes are sometimes Halflings or Hobbits or (god help me) Kender, but there’s this race of small people who are inventive, tinkery, and have these strangely modern compound names.

Now, names that are modern words isn’t unreasonable, in my culture. I know a number of people who have names like Cloud, South, West, Green or so on. But those names are all old and they’re rarely compound like that. What’s really interesting about the Gnome names is that Gnome names are words in whatever non-Gnome language they’re presented with.

It’s a well-accepted piece of modern lore that people’s names have meanings, phrases or terms that they owe their derivation to. Even basic and boring ones like James and John and Peter have some connection to an earlier iteration of the name, some thing you can translate them to. Gnome names, however, come translated already – Cogwhistle Buzzthump is two compound words in the language of the reader (in this case, English).

From this I can derive two things:

- Gnome names are some kind of agglutinative language, made up of bits you can jam together

- Gnomes think humans are total assholes who will translate their names into English rather than try and get them right

This is, incidentally, a problem that a lot of recorded history of Native Americans in the United States have to deal with. Peoples names get translated like they’re not names, but are rather titles. So instead of referring to when Mo’ohtavetoo’o was betrayed by The Strong And Steady Digger, we refer to Black Kettle being betrayed by George Custer.

I dunno, Gnome names are racist or something (they’re probably not).

The One Good Bit Of Punisher Season 2

I thought, for a while, about doing a Story Pile about Netflix’s The Punisher second season. I mean I watched the whole thing, how bad could it be, I mean, if I spent that time, surely I could divine something to talk about in it. Then I kept finding it was easier to come up with other things to talk about than it, and with the news that Netflix’s MCU is ending, it seemed somewhat pointless.

I mean the most interesting thing to say about The Punisher season 2 was that it was impressive the way it maintained the badness of the first season. Like, normally media this bad is bad because nobody in charge could tell how a thing was meant to work, and the result is unfocused and sluices down to a worst point. The Punisher instead manages to be bad in a way that’s consistent and reinforces the failures of the previous season, and that’s impressive, in a way.

And that’s the problem with an article about it. Because an article about this series would mostly be me telling you how it sucks just like the last one.

Instead, I want to talk about one scene, one snippet of a scene, even, and it’s the best thing in the whole show. You don’t even need to know any of the characters or much context. It’s spoilery, though, so if for some reason you wanted to take the series seriously and avoid spoilers, now is your chance to get out.

(Why, though.)

The Dwarves Wrote The Histories

An idea I’ve never been able to shake is the D&D racial animus between dwarves and orcs-and-goblins 3.5 D&D presented. This is an idea that stems basically from your Tolkein source material, but it has a weird side effect when you interrogate it, because of time.

Dwarves are so good and so used to fighting orcs and goblins that they have all got an advantage at it. Like, this is stuff baked into their culture so deep their pastry cooks and their ponces all know how to lay into an orc a bit.

Look at this chart (obtained from d20srd.org):

| Race | Middle Age1 | Old2 | Venerable3 | Maximum Age |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human | 35 years | 53 years | 70 years | +2d20 years |

| Dwarf | 125 years | 188 years | 250 years | +2d% years |

| Elf | 175 years | 263 years | 350 years | +4d% years |

| Gnome | 100 years | 150 years | 200 years | +3d% years |

| Half-elf | 62 years | 93 years | 125 years | +3d20 years |

| Half-orc | 30 years | 45 years | 60 years | +2d10 years |

| Halfling | 50 years | 75 years | 100 years | +5d20 years |

Ignore the halflings and elves and all that, we’re focusing now on the Half-Orcs and Dwarves. Goblins in the Monster Manuals are said to live a variety of years, depending on which one you read, but they tend to hover around 30 to 40. Orcs and Hobgoblins have a similar range, and Races of Destiny presents a Half-Orc’s lifespan as capping out at an absolute max of 80. By comparison, a dwarf’s maximum age is 450.

A dwarf, by middle age, has seen the rise of nine orc or goblin generations.

Consider what that means to humans. If I fought the man that killed my grandfather when they were both young, that man would be old, now. In this case, an orc facing the dwarf that killed his grandfather is facing someone who time has not weathered at all.

What’s more, the reasons, the motivations for doing so – they’re not around. When you look at how these books present orcs, goblins and dwarves don’t have cities or civilisations; they have things called warrens and camps. They’re presented as being kind of what we’d normally consider ‘pre-civilisational’ and that means they don’t do things like agriculture or writing books that tend to be how we, as people who do agriculture and writing books consider a hallmark of being ‘real’ cultures. Let’s set aside the obvious bias here, and just look at the effect. It’s going to be very hard for these Orc and Goblin cultures to have clear records of what happens when they have wars with the Dwarves.

They don’t have maps or border or maybe even the concept of a country. They’re typically represented as illiterate and use a script that’s not even their own native tongue to write in when they do. They don’t get to know why the dwarves rolled in, but the dwarves do. It’s one of the most obvious things about the dwarf culture as it’s represented: They are old, and they are stubborn, and they remember old grudges.

From the perspective of the orc, the dwarf is an implacable unstoppable juggernaut that emerges from the mountains to kill a generation for reasons that are never truly scrutable. Their armour and weapons are older than your civilisation. They are like cataclysmic storms.

And the dwarves have been doing this for so long that everyone knows how to fight an orc.

Everyone.

And the orcs and goblins and hobgoblins don’t get a bonus against the dwarves.

Consider who’s telling us these stories; the people with their forts and their steel and their axes and their maps and their records who teach their members to murder goblins and orcs and hobgoblins that they never have met and never have any reason to meet. A clockmaker isn’t going out of their way out of the fortress to go forage around in dangerous hobgoblin areas for gear parts. But he knows how to stove an orc’s head in.

Here’s your lesson, game-design wise. These decisions were all made to reinforce flavour from a fiction: In Tolkein’s books, dwarves and orcs were at war, and dwarves were player characters and orcs weren’t, so dwarves got a bonus to help players who play dwarves be excited to fight orcs. The ages follow through from Tolkein too – created monsters like the orcs don’t need a culture, they’re just there to be fought, so it doesn’t matter if they’re short-lived. They’re a byproduct of someone else’s war machine. Dwarves are meant to have long kingdoms and take a long view, so they have to last longer than humans. It all makes sense.

But the mechanical choices made here to represent this flavour create an eerie kind of genocide-capable culture that seems to exist to punish a nearby stone age culture for crimes that culture may not even understand as crimes.

These dwarves seem like they’re really bad, to me.

The dwarf-goblin header art is from Jeffry Lai on deviantart

The bumper image is the cover art for Battle of Skull Pass, which best as I could find was by John Blanche

Story Pile: Neon Genesis Evangelion

DISCOURSE CONTAINMENT

Neon Genesis Evangelion is twenty-five years old. It is not a new series. It is not a series lacking in exposition or consideration or study. It is an important text but it is also vitally an old text. There is a degree to which the conversations around Evangelion are not just uninteresting, but are now completely tedious.

You might have seen it the first time, ever, this week. You might be planning on watching it. You might be wavering on whether or not you do. After all, it’s a Big Deal, why not?

There will be no meaningful spoilers for Evangelion. I’m barely going to talk about anything that’s in the show at all. But I am going to talk about this series and some of the reasons it matters, and the most important fact, that this series means a lot less than it matters.

DISCOURSE CONTAINMENT