March 2019 Wrapup!

Curse this smarch weather!

Game (Barriers, Readings, Reviews)

Sometimes I’m cautious about using the term game review when I talk about games in Game Pile. We’re not usually sure what a review of a game is, in language terms, except when people are talking very specifically about games as consumer product getting consumer guidance.

I don’t do that though – I mean, I do account for the consumer product of the games I talk about. Often I’ll offer reasons why you might like a game, or things about that game that are good guidance for when you buy it. That’s not really the primary way I talk about games, though.

One thing I’ve been thinking about a lot is how when I write about a game’s play experience, it can be viewed as autoethnography, but that’s a really obscure term and it makes me sound like I’m distancing myself from everyday talksy-about-gamesy people. There’s a barrier put in place when you use academic language, and while I want to connect non-academic people to concepts they may understand and be able to use from academia, if I do it by teaching them just plain jargon, I feel like I’m mostly teaching people unuseful things they won’t use. Even if I’m doing autoethnography, that doesn’t mean saying this is an autoethnographic survey of this game is just alienating as hell.

I’ve toyed with calling them readings, the way that that term gets used in both critical media and academia. This is my reading of this game, for example. That’s interesting because it presents my take as a sort of unified set of details that are meant to harmonise together. That would actually ask for me to do things differently, too, though, if I wanted to mimic a reading. Readings are great if you have a particular definitional vision of a work, too, where you want to present a version of events where this is what I think happened, or sometimes to frame it as if this happened, here’s an idea for what that means. I do readings sometimes – my take on Voltron is a reading, for example.

Most of the time, I don’t do readings of games. I tend to look at them in terms of design, or how they’re made, or the plot, or even single beats in the plot. Games tend to be kind of bigger than other media, it means there’s a lot of room to write about a lot of things when you write about a game. Some of my game articles are readings but that’s not to say that’s what I do.

And thus we loop around this thought, again and again, and again. What are they, if not reviews? These are thoughts and writing spurred by the retrospective consideration of the game, too. They are literally my thoughts upon review of the game.

I guess in the end, while this point of language bothers me just a shade, it’s a point I’m trying to get over. The idea that these things aren’t reviews because they’re not consumer examinations or because they’re focused on story or design is to cede the entirety of review to a glorified price guide.

Therefore, my articles about videogames, are game reviews.

Fight me, my own brain.

Game Pile: Assassins Creed Remaster

This month’s video is an experiment! Continue Reading →

D&D Memories: Shen Marrowick

We do this these days, right?

We talk about our D&D Characters?

Okay.

I am a firm believer in the idea that when you present a character to the players at the table, they need a handle on the character. They need to be able to grasp the character quickly so it’s often best to start with a basic archetype or story point. You want to occupy the space in the story, you don’t want to have to explain that place you want in the story.

Continue Reading →British Currency

Years ago, as one of my research projects, and to show off a bit, I talked about Australian money, because Australian money, unlike most other cultures’ money, is good, or at least, better than yours, or, most importantly, better than America’s, which is really bad. At the time I had the fanciful idea of maybe examining a bunch of different culture’s money, but mostly they all repeat the same basic-ass mistakes as the American money, which I think is possibly because American money is the template a lot of other countries use (why).

Still, there are at least two other countries whose money I think is worth talking about, and we’re doing one of them today: the British currency. Talking about Australian money took a long time, weeks, with stories about every figure involved. Talking about American money took a short dismissal, because all American money is bad.

British money needs a little bit more space, but less than it should.

Let’s go.

Caillois and Rosewater

This is about Magic: The Gathering, but it’s not.

It’s about Academic reading, but it’s not.

In Roger Caillois’ book Man, Play and Games, he describes a bunch of concepts that make a case for how games are important, what they do, what they mean for culture, all that good stuff that we can use in game studies. In this, he laid out his notion of both a sliding scale between two points for the way games work then he describes four types of ways players engage with games.

Mark Rosewater, the head designer for Magic: The Gathering, has talked about types of players and who they design cards for in terms of a sliding scale between two points for the things that appeal to players, and then describes three types of ways players engage with the game.

The sliding scale in Caillois’ work is between ludic games and paidic games. Ludic games are about clearly defined rules. The more tightly defined rules are, the more likely it’s ludic. Chess is very ludic, for example. Paidic games are about freedom of play, the capacity to create rules or subsystems or discard rules as you play. Improv games, for example, are very paidic.

In Rosewater’s work, he describes the idea of players caring about the feel and lore of the cards they play with (an idea first positioned by Matt Cavotta), and the players who care intensely about the rules of the game state and don’t care about that creative space. These are described as Vorthos and Melvin.

In Caillois’ model, his four types describe games in terms of them having attributes that give people reason to play:

- agon, games of competition

- alea, games of chance

- ilinx, games of vertigo

- mimicry, games of impersonation

Rosewater’s model describes three types of players, and why they play:

- Timmy/Tammy, who wants to feel something

- Johnny/Janey, who wants to express something

- Spike, who wants to achieve something

Now, these don’t directly map onto one another; it’s hard to see how ilinx connects to the Tammy/Janey/Spike model. I personally feel that it works well as Janey’s thing, where flipping a card and rolling a dice and seeing what your opponent can do about it is a feeling of being disconnected and helpless that you can enjoy. But that’s fine, it’s a narrow tip to a broader pen.

Also, Janet Murray in Hamlet on the Holodeck points out there’s a fifth type of play that Caillois doesn’t consider – the player who plays to enjoy the idea of the rules interacting. That rules that nest and set against one another in a satisfying way offer enough of a reason to play.

I’ve asked the crew at Wizards if Caillois informed their vision of the psychographics, and as of this writing I haven’t received an answer. Informed by their history, I think they devised their player psychographics independently, and the Rosewater model is missing some basic components.

These are two very good ways to look at game design; they both fundamentally want to focus on why someone plays, with Caillois framing it in terms of big, cultural ideas and Rosewater framing it as the choices of an individual’s feelings. Caillois (and Murray) take into account another two different ways to play, two more ways you can make games and things you can implement in games that people engage with.

One of the reasons we look at Caillois’ model is because, well, he was a French academic, and he wrote about a topic, and other people wrote about it subsequently. At the same time, though, Caillois’ ideas include a lot of super gross colonialism. His whole vision of cultures that aren’t western European talks about them condescendingly, the notion that their destiny was to be conquered or colonised, because of the games they play. The Rosewater model, on the other hand, is a living games text, expressed not in an academic book written by one person, but algorithmically sorted by a game that’s been non-stop produced for twenty-five years.

It’s not that the Rosewater model is better, I just feel it’s a bit easier to share. I don’t need to assign it one or more Yikes.

Is this some bold position, ‘we should use Rosewater instead of Caillois’? Nah. Is it some brilliant academic insight, ‘MTG R&D bites on Caillois’? God no.

It is still interesting.

Continue Reading →Story Pile: Touhou

Oh, yes really.

We’re doing this.

Touhou Project, Touhou, or Project Shrine Maiden, or whatever you want to call it, is a set of characters coexisting in a somewhat loosely aligned storytelling space first originated from the work of Team Shanghai Alice, which is to say, the entire staff of Team Shanghai Alice, which is to say, one person, ZUN, who has made (at least) 27 Touhou games since 1996. While the conventional vision of these games is bullet hells, and ZUN’s work definitely features that, there are Touhou games that ZUN didn’t make, and these include puzzle platformers, dungeon crawlers, RPGs, even a one-on-one fighting game.

The Guinness Book of Records, as of 2010, has instituted Touhou Project as “the most prolific fan-made shooter series,” which I think is a really stupid description because it suggests that ZUN is somehow a fan and not a creator in their own right, but it’s not wrong because a large body of the work that ‘is Touhou’ is not made by ZUN, and that collected third party stuff includes professional products.

This is extremely weird: It’s weird because conventionally, the vision of how work like this gets made has a certain degree of ownership and permission.

You can’t just make a Touhou game, I assume, you have to ask if you can.

At least, that’s how it works in the places I’m used to working.

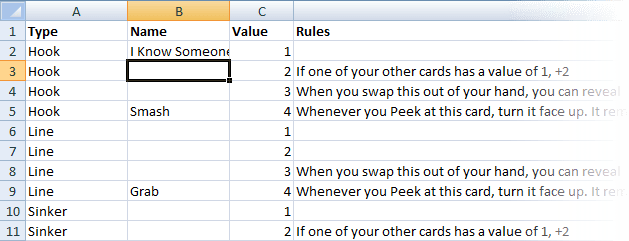

Continue Reading →Making Hook Line Sinker

Hey, check this out.

This is what I call the cover card for our game Hook, Line & Sinker. At the time of writing this, I’m still testing this game, but I like this aesthetic for the game, and unless it tests badly for use, it’s probably going to stay this way.

I made this. This is my art. I’m really happy with how it looks, and I figured I’d like to show the process I went through to make this card, this specific card. Below the fold, then, is a step-by-step process of showing how I made this, and this is very close to my first look. This was all done with like, basic tools that you can find in most every graphics program.

The Tail of Spite

Back in 2018, Dinesh Vatvani, a python programmer, took a set of analytic tools to the BoardgameGeek top 100. I have said some mean things about BoardgameGeek in the past, like how it’s a site that ‘loves lists as much as it hates women’ or ‘looks like an android’s uterus’ or ‘has a community that are shockingly comfortable with being the worst kind of racists,’ but one thing it’s generally regarded as being pretty solid at is presenting to a general audience a lot of data about whether or not a game might be, in some vague way, ‘good.’ It’s got a ranking system, you see, and that ranking system – well, it’s a system. Systems are right, aren’t they? It’s like algorithms.

The hypothetical idea is that BoardgameGeek, by aggregating a large number of opinions, this analysis avoids having a ‘bias’ and is instead presenting a kind of objective data.

Now, obviously, this kind of analysis is going to be as biased as any self-selecting group, and Dinesh’s analysis seeks to tease out a number of different factors. The full article is definitely worth a read, but in this, he introduces something extremely interesting, which he dubs the Tail of Spite.

The Tail of Spite is the way that:

A curious feature of the graph above is the tail of games of low complexity and low ratings at the bottom left of the plot. This “tail of spite” consists of relatively old mass-appeal games. Every single game in the tail of spite was released pre-1980, with many being considerably older than that. The games that form the tail of spite are shown in the table below:

What fascinates me about this tail of spite is that these are games that, with some degree of objectivity, seem to be successful. Some of them aren’t even exploitative like Monopoly – I mean who owns Tic Tac Toe? Who’s getting rich off kids knowing how to make that game on their notepaper. No, these games are games with wide-spread mainstream appeal, that do their jobs, are largely not broken and rarely poorly produced, but they’re extremely well known. They are not so much rated as they are resented.

I think this idea, that of a ‘tail of spite’ is a useful one to have. Your biases won’t just express in over-rating the things you like – you will also be inclined towards being more harsh on things you have personal distaste for.

Anyway, Monopoly sucks.

Game Pile: Keen Dreams

Oh hey, a Game Pile about a Commander Keen game! We’ve done that before! Twice!

And right now, it’s amazingly actually timely, kind of, because unlike how I wrote about Wonder Boy 3 just in time for the announcement of the remake, I had this plan lined up just as Keen Dreams dropped on the Switch.

On the Switch.

What the hell?

Who was seeing that coming!?

Released in 1991 under the Softdisk label, Keen Dreams marked a turning point in Commander Keen design. The first Keens were made as an exercise in smooth scrolling video on a PC – an attempt to replicate the movement of Mario Bros kind of games, and which wound up being – you know what, just go read Masters of Doom by David Kushner (no relation to that one) and learn about the arc that takes from Commander Keen and Softdisk to literally the entire modern landscape dominated by team-based multiplayer shooter games. Suffice to say this is legitimately one of the stepping stones on that path.

If I was a fairer writer, I’d tak about Commander Keen 3: Keen Must Die!, and I guess, here, bonus Game Pile: Keen Must Die is an afterthought of a game and makes the moral weirdness I mentioned about Commander Keen 2 both front-and-centre and obvious. Like it’s pretty much impossible to finish Commander Keen 3 without shooting someone’s mum, which is pretty bleak as a story beat to put in a videogame.

Keen Dreams is a… decent game. It’s fine. It’s alright. It’s definitely weaker than Keen 4 and a little bit better than Keen 3. There’s less game here than you’d think, less spectacle, less fun exploration, and there was a point where this game was entirely available for free, but it’s certainly worth more than nothing.

Making Fun: Years Later

Starting in November 2017, I decided that, with enough attempts made to explore methods of how, that I would start uploading videos to Youtube. I decided to build on my then-recently-finished Honours thesis as an experiment in seeing what I could create that could suit a rapid-fire fast-talking Youtube content form, and as a direct result, my first video series, Making Fun was made.

It’s been a bit over a full year now, and I thought I’d spend some time to look at these videos and see what I thought of them, what lessons I had learned, and what lessons I would recommend.

A Low-Value Endeavour

In early January, the Australian government announced a grant of $6.7 million for a 39-stop circumnavigation of Australia in 2020 by a replica of James Cook’s Endeavour, in ‘celebration’ of the 250th anniversary of this colonial murder hobo whose main accomplishment is to get stabbed in the chest with a spear because the king of Hawaii refused to LARP along with Cook’s notion that he was a god.

This is something of a sore point, because celebrating any achievement of Captain Cook’s life is done by recognising that Captain Cook had a life, and that involves talking about Captain Cook and mentioning the much more miserable stuff he did like, you know, the invasion and initiating all the genocides and the colonialism and whatnot.

I said some stuff at the time, some of which turns out to have been incorrect, but mainly also this gave me an excuse to talk about boats which is subject near and dear to my dad’s heart, which is pretty weird, now I say that aloud, because I don’t actually care that much about it.

Nonetheless, this is a chance to correct myself a little and phwooar. Look at that… skimmtren. Ain’t that impressive.

(I have no idea what I’m doing)

First things first: The Endeavour replica this story is about is an absolute marvel of engineering. There are some modern components of it, mainly an engine that’s kept in the old Hold where you stored rotting bad food full of worms and also any people you wanted to ha ha, transport (probably never happened don’t worry about it) but those things are there to basically make this boat something other than a coin-flip death trap when taken out to the open seas. When you set that engine and its requirements aside, though, the boat, is made period-appropriate, down even to its eyelets in its sails, using woven cord, rather than metal eyelets.

The Endeavour was being developd in honour of the bicentennial in 1988, and finished in 1993, 26 years ago. It is an incredibly impressive, technically amazing achievement. I’ve been on it, for a school trip. It’s really, genuinely amazing, not a word of a joke, that it exists.

The journey itself is a bit of a swizz. Cook didn’t circumnavigate Australia (he did circumnavigate New Zealand, which both Australians and New Zealanders will firmly explain is not the same thing), that task was done by by Matthew Flinders in the Investigator or possibly by Chinese Junk traders. They were traders in Junks, a type of boat. Not that they came here to sell the Indigenous peoples their miscellaneous crap.

The circumnavigation of Australia is, let us not kid ourselves, about getting it to Perth, then back to Sydney, and filling the time in between with a bunch of school trips and the nebulously-hoped-for tourist dollars? it will? bring??

That 6 million dollar sum is important because if you don’t remember this boat exists that headline makes it sound like it’s 6 million to get a replica of the Endeavour and go on a tour for a few months, which is almost reasonable. But it’s not.

That’s the ship’s travelling upkeep cost.

The Endeavour is a period appropriate boat. Just travelling around the country costs about 6 million dollars. It is expensive to move because it is a period boat and it’s meant to be kept in pristine condition because it’s a historical replica piece. Now, you might not pay attention to historical replica boats from a period of history you don’t care about in a country you don’t care about, but I fortunately am cursed with actually remembering my abusive school environment, so I do remember this boat.

Back when I first wrote about this, I mentioned that the boat had been ‘sold’ multiple times, or rather that they’d tried to sell it multiple times and it turns out, with deeper research, that wasn’t the case. It’s not that they’ve tried to sell the Endeavour. It’s that they’ve tried to sell an Endeavour.

In England, there’s a second Endeavour – and that doesn’t have the same largesse ours does. The Australian Endeavour has been financed by government grants and private donations from various businesses, and the thing is, by all observation, a money pit. Simply put, the Endeavour exists by people paying money to keep it existing, and people pay it because the alternative is letting the Endeavour go around unfinanced. I can’t tell you who donates to it (beyond the Bond corporation, who paid for it to get made then donated it to the country).

Still, the thing is…

Nobody cares about this boat.

It’s going to travel around, conspicuously land the most times in the most racist state, be the subject of a lot of school trips, some well-meaning positive historians are going to try their best to wed the event to actual discussions of Cook, and that’s pretty much it. It’s too expensive to keep and it’s too important to junk and it’s too worthless to sell.

And yet if they scuttle it, I would be genuinely sad and I don’t have a good reason why.

I mean it’s not the boat’s fucking fault Cook was a monster.

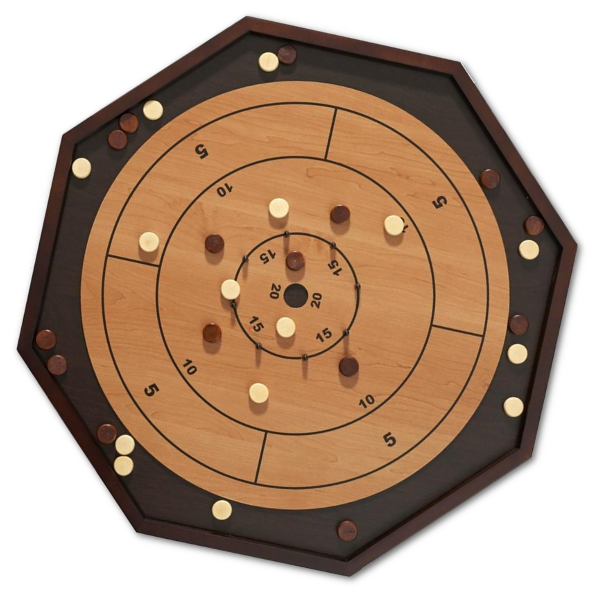

Crokinole And Doing Just Enough

Few things are going to go so well as to make broad, sweeping statements about what you can derive from a culture from observing its games. Roger Caillois offered that idea, and he was a shocking all-purpose super-racist, like a Voltron of racism, bolting together orientalism and exoticism and a kind of intellectual academia that formed The Head(lessness).

Caillois was so convinced that the destiny of cultures could be seen in the games they played that he dedicated a book to the task, a book that I have had gleeful fun making fun of lately but which also has some terms that we’ve kind of gotten very used to using, terms like ludic and paidic in terms of game design. His model of games as forms of engagement was to see them in terms of how people got involved with them and what that meant they got out of them, and then from that, to try and draw broad, elaborate strokes about what this meant for cultures that just happened to align with western Europeans and mostly French academics just being the best people, and clowns were evil.

Now I don’t think that you can’t draw some conclusions about cultures and their games, particularly in that when I think about Canada and games, the three that spring to mind are curling, crokinole, and ice hockey, and of those games, two require you to have a ready supply of ice in fairly large spaces. When a game can be played with commonly available stuff in common spaces, and doesn’t need a lot of speciality equipment, it becomes more likely that people will play it, and it can spread through a culture more readily. There isn’t a big curling scene here in Australia, a place that hasn’t had common ground ice in its capital cities or residential areas since those places ever existed. It’s kind of doable to look at Canadian games and think ‘the attributes of Canada as a physical space helps to encourage these games.’

It’s not like my opinions of games is coming from a space of serious expertise, either; Canada is a really big country, and those three games are trying to represent four hundred years of history across literally the second largest country in the world. The game of ear pulling has been played in Canada for literally three millenia and Ice Hockey is relatively recent by comparison.

Still, when I look at these three games, something that strikes me about them all that they have in common is that these three games are not about doing something to the limit of one’s ability. They’re all about, or have rules to encourage, you to do just enough.

This isn’t unique! After all, games like bowls and blackjack are also games about not doing too much but neither of those games are about dealing with the dynamic, slippery surface of ice, or the crokinole board and its skiddy polish.

Is there more to this? Is it a secret insight into Canadian culture?

Have I cracked some Cailloisian code?

No.

It’s just a coincidence. An interesting coincidence, but a coincidence.

But it’s fun, sometimes, to notice these things, and think about how you might do things differently.

Story Pile: Bleach (The Movie)

Conventionally, I open discussion of media for the Story Pile in a pattern. It’s literally a template – I have it laid out in front of me right now. Here, the segment is titled introduction and that’s where I put something that snappily sets the tone for the whole thing, but,

but

how.

Just how do you introduce this? There’s the technical – Bleach (2018) is a live-action movie based on the anime Bleach, based on the manga Bleach. Great, that’s a start. It’s also really useless.

There are, right now, five basic ways to know of Bleach, a sort of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Weebs. You have the absolute bottom tier, where you have no idea what Bleach is. You are the majority of the world, blissfully safe and ignorant of this strange story. This is the outer realms.

Then there are those who know Bleach primarily as a punchline. Then there are those who know it, and who wish to tell themselves – falsley – that Bleach is good, has always been good, and any complaints from people disliking it is a sign of an inadequate anime fan. Then, there are those who know Bleach, who were there for Bleach, who were part of Bleach and when Bleach failed them, they were angry. They speak of Bleach as if it was never good, and they are mad.

Finally, there is the top tier. Those of us who know Bleach, and know how Bleach is bad. We know that Bleach failed, but know that at the same time, Bleach was failed.

Continue Reading →Broken Fridge Light

The light in our fridge doesn’t work.

It hasn’t worked, literally ever. Our fridge was second hand, and it is great, and I am so glad to have it. It has a good energy rating. It has been a reliable, workable, completely great fridge. And it has never, not ever, had a working light.

Tonight, I got up, as I could not sleep, and I wandered out to the kitchen to have a drink of milk.

I opened the fridge, and looked inside, squinting, thinking, oh. the light’s broken.

I have this thought about once a month.

I am so used to the idea that fridges have lights in them despite having had a fridge without a light for over FIVE YEARS, I am still somehow completely expecting the light to work when I open the door. Human brains are weird.

Top Dog

Games are filled with opportunity for discovery. When you’re exploring a device with low stakes, you are in that time, playing with it – seeing the boundaries of what it allows. It is the play of a gear, more than the play of an actor. Play is how we find the limits of things.

Okay, rewind. A story. A story of a specific thing in a specific place.

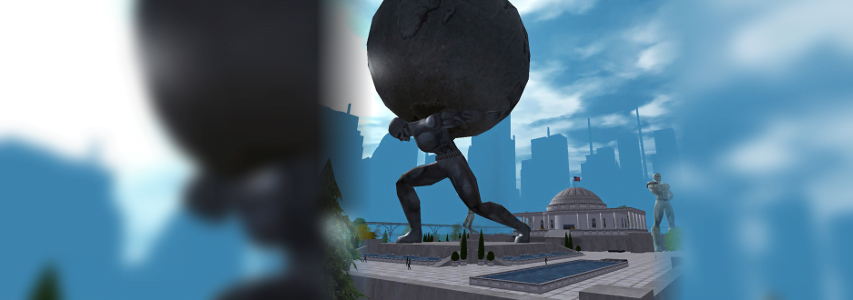

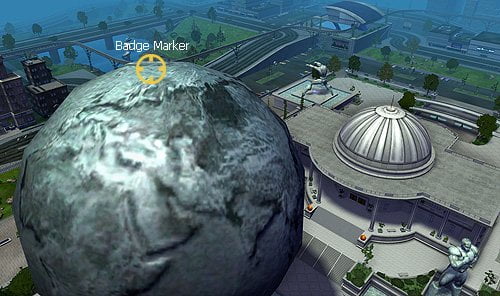

Back in the day, in City of Heroes, when you first made a character, you’d complete a short little tutorial, and be dropped in front of the steps of the Atlas Statue in Atlas Park. It looked like this.

It’s a common thing for players to talk about, the first moment the got a flight-related travel power. It was usually hover, but sometimes it was a jetpack. However you did it, when new players gained the ability to leave the ground, one of the most common things they’d do is use that power to fly up to the top of the Atlas Statue and look at what was there.

What was up there was an exploration badge.

These badges were a bit like achievements. You could put a badge on your character and it’d display under your name. More important than what this badge could do, though, is what this badge did.

When you explore, one of the most disappointing things to find is nothing. I have memories of struggling up mountains in World of Warcraft and New Vegas and finding blank textures and no reaction to my presence, a sign that I hadn’t actually achieved something difficult but just had done something the developers had never expected. That taught me to stop trying those things, to stick to the path, to give up on exploration and excitement. I turned the gear all the way in one direction, and the game didn’t react well to it, suggesting I never do that again.

In City of Heroes, you tried something, and the game found you when you got there, and said hey, yeah. This kind of thing works.

The Top Dog badge encouraged players from the earliest point to always look on top of things, around things, to think in terms of what counts as worth exploring. It was a good idea, and I think that it rewarded players for being playful with the world.

Game Pile: Braid

Braid, the 2008 videogame by Jonathan Blow, widely heralded as the first Xbox Arcade indie game and the dawn of a new era of artistic expression in videogames and the newly democratised marketplace, is in an uncited claim on its Wikipedia page, in contention as ‘one of the best videogames of all time,’ which suggests that this little indie game is very important and smart and deep, like other best videogames of all time on the wikipedia list, like Ninja Gaiden.

For obligatory game-as-game-context, Braid is a side-scrolling puzzle platformer game with your classic runny-jumpy-climby, a beautiful hand-painted art style and puzzles that focus on an engine that can do endless, smooth rewinding of every game entity all at once. This has a lot of clever design in it, and thanks to the endless rewinding, you can design the whole game around really challenging puzzles knowing you can always reset them and try again.

It’s decent.

It’s fine.

It’s regularly quite cheap, and it definitely isn’t overpriced.

Spoilers for Braid, ahead.

Continue Reading →Blocking out a Card

Hey, here’s a thing I was working on in February. You may have seen it on twitter.

Here’s a cut link because this is going to show full images of cards and those things are loooong. Oh and pre-emptively, these cards have been munged by Twitter because I could not be hecked to re-export these progress shots.

Form Informs Function

I’m looking at this game, Yamatai.

It’s this big, bulky beast of cardboard, a real classic Euro of dear god, there are how many bits? At its root, it’s a game of laying paths and fulfilling economic requirements. In fact, you can almost punctuate Yamatai as a sentence with a lot of asterisks – you place boats* on a map* to fulfill goals* that earn money* to build structures* to earn victory points*. And every single * indicates a place where the game has a specifically designed system meant to make that particular action more complicated.

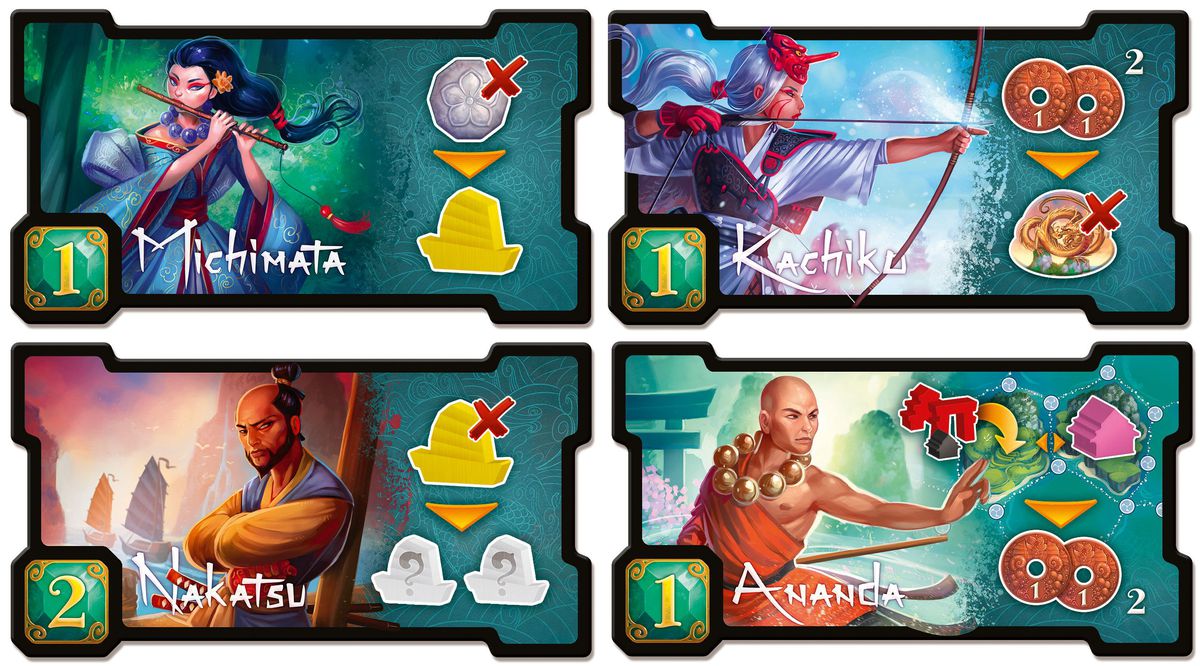

If you remember me talking about alignment systems as plumbing, then this is the kind of game where you work with a lot of plumbing to make it work. It isn’t a bad idea, most games are simple systems rendered difficult by complications after all, Bernard Suits and the willing overcoming of optional difficulties and what not, but anyway, in this game, there are these tiles that determine special game actions you can take and how fancy your faction is regarded, known as Specialists. They look like this:  This is how they actually look. They have these names. The rulebooks specify what they do, but never who they are, and while we can talk for a bit about mechanics informing character, it does feel a bit like a swizz to turn these people into these tiles that represent actions. These people aren’t reduced to what the can do, they’re reduced to one action only, which is good for a big and complicated game that already has too many bits going on.

This is how they actually look. They have these names. The rulebooks specify what they do, but never who they are, and while we can talk for a bit about mechanics informing character, it does feel a bit like a swizz to turn these people into these tiles that represent actions. These people aren’t reduced to what the can do, they’re reduced to one action only, which is good for a big and complicated game that already has too many bits going on.

Why are they people, though?

These could be machines, or flags, or they could be brokered trade details (and maybe even decorated to look like them) or faction histories or – there are lots of things these tiles could be. They’re not. They’re people. They’re named like they’re people.

To spin this around to one of my own designs, I’m working on this small game (at the moment – it’s probably long done by the time this goes up) where there are only eighteen cards, and they each represent parts of a plan. What’s tripping me up at the moment, though, is the challenge of what verb form to put the card names in.

I’m not trying to bag on Yamatai (here) for reducing Asian People To Objects (again, here). I’m thinking about the ways we talk about mechanical objects and their purposes. How we choose them. How to make them consistant.

Janet Murray once expanded Caillois’ model of gameplay with its agon and alea and mimicry and ilinx and described a form that Caillois hadn’t considered, of rhythmos. Her idea was that some forms of rules satisfaction came from making rules that worked cleanly together as rules, and that helped drive gameplay. This is a very real effect, and one that you’ll notice if you miss it.

And so, here I am, up late, worrying away, like a beaver at a twig, thinking about conjugation and the card-tile non-people of Yamatai.

MTG: Tiny Cube

Let’s assume you’re familiar with Cube.

Okay, no wait, let’s not assume. The basics of Cube is that it’s a pool of cards and you draft them and play Magic: The Gathering with what you’ve drafted. An in-depth discussion can be read here.

Now, let’s assume you’re familiar with Winston Drafting.

Wait, no, that’s a bad idea. Winston Drafting is the idea of a format for drafting cards between a small number of players – two or three is the usual numbers. You Winston draft by slowly generating piles that become more and more desireable. You can read an in-depth discussion about that here.

Now, let’s talk about Tiny Cube.

Story Pile: Castlevania

If you’d told me that Netflix were putting together a Castlevania series by Warren Ellis and it was an Anime I’d have to have assumed you were working through some sort of nerdy fanboy madlibs, like the output of a twitter robot designed to generate quote-tweets from people inclined to go ‘omg that’d be great.’

It’s such a confluence of edginess; the game is not obscure, but it’s sub-mainstream enough to seem a little edgy. Netflix are by no means a small production house, but Netflix original animation is certainly not on the level of houses like Disney. Making an anime as a specific, separate genre of thing, is also, again, not actually not-mainstream, but seems non-mainstream. And then you throw in Warren Ellis, a man who’s produced tons of comic books and the licenses for tons of movies, and even a TV series, a man who has been kind of all about being the not-the-mainstream version of mainstream comics for large chunks of his career.

Warren Ellis is almost perfectly positioned as everyone’s second favourite comic book author; excellent and creative, but also so aggressively Very Online that you could be forgiven for thinking he’d sprung from the fever dreams of the internet itself. Ridiculous and posturing, energetic and digital, he’s also somehow managed a career as long as his without actually massively embarassing himself on issues that comic book authors didn’t seem to realise mastter that much. There’s no lingering false vision of his work like Mark Waid has, no uncomfortable sensuality of magic that Grant Morrison has, and unlike Akira Yoshida, Ellis exists.

He is the Patrick Swayze of comic book authors; great but so often overshadowed by excellence. You need to know comics to know Ellis and you need to know why Ellis hates comics to love them like he does. Ellis is a great big pink sparkly mullet of an author in an industry peopled by people trying to get themselves taken Very Seriously when they write about the spangly man in the cape with the funny knickers.

This set of factors, coupled with people talking about how brief the first season of Castlevania was pushed me away from it – it seemed that three episodes of NES-era narrative via Ellis might be the perfectly sized dose to completely blow the minds of people who had no real familiarity with any of these factors, that the sheer surprise of the series would set people off, have them curious for more, without it actually being in any way a necessarily good or enjoyable experience for those of us who knows what it’s like to wait six months for a comic issue that’s been A Bit Delayed.

Then I watched it, and…

Oh boy, is this the Good Shit.

Why Does Christian Media Suck Ass?

One of the most dangerous things to fundamentalism is a desire to be good.

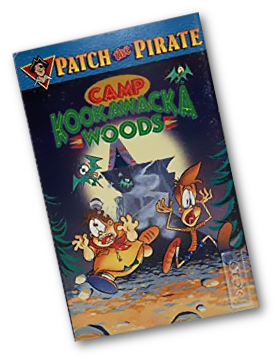

This post was in part spurred by relistening to the absolutely dreadful Camp Kookawacka Woods by Patch the Pirate, a subject so dreadful I feel a bit like I should do a rewatch podcast just so I can impress upon people just how utterly yikesy the whole franchise is at its core. Listening to it, though, with Fox, I had to let her know that some of the songs (that were performed pretty well) were hymns, and some of the songs were based on old campfire songs, and some of the songs were rip-offs of pop songs, and how the whole thing was just so cheap and hacky.

This is a pattern.

If you’ve ever gone looking for what I call Christian Replacement Media, you might have noticed that it’s kind of bad? Not necessarily remarkably bad, no glorious-trainwreck The Room style hubristic excess, it’s just that the best of these movies tends to crest a Pretty Alright level. Probably the best Christian Media Escapee band is Five Iron Frenzy, which is to say that the entire right-wing music machine was able to produce a single good ska band of leftists, which considering the number of times they’re rolling that dice is not a great average. The movies, the branding, the graphic design, almost everything you see in the Christian Replacement Sphere is a slightly shit version of whatever it’s replicating.

Oh, they’re often expensive. Yet even the things that are expensive in this space tend to be gaudy, or overpaid for. When it comes to art and media these stories are almost always just slightly inferior, confusingly weak versions of things that aren’t actually that hard to get right. There are bestselling Christian authors whose work crests the quality of maybe a decent fanfiction.

This is weird though! It’s not like being in the Christian cultural space asks you to be bad. Assuming a random selection of the Christian media space is an equally random selection of the culture of the world, you have to assume that a certain percentage of them are just going to pick up decent artists.

What gives?

I have a theory.

No, wait, I have a hypothesis.

The hypothesis is built out of my experience, and the experience of a few ex-fundie friends. We’ve talked about it, about the things that pulled us away from the faith, and how those things that pulled us off the path were not the fun, excellent temptations we were warned against, but inevitably, a drive to be good at something. I didn’t learn my eschatology and biblical foundational theory because I wanted to prove it wrong. I learned it, because I wanted to be able to prove it right. Nonbelievers would come at me with arguments, I was told, and so I wanted to understand those arguments so I could show how they were wrong. One of my friends wanted to do excellent work rendering graphics for their church, and so they wanted to study how graphics worked and how to convince people with the icon rendered in front of them. Another was driven by a desire to Make Computers Work.

None of us set out to fall.

The basic idea is this: To be good at something requires context and practice. Gaining either of these things inevitably exposes you to the ways in which fundamentalist church spaces fail.

It’s not that church seeks out awful artists. It’s that the modern American church is a sorting algorithm that wants to throw out the good artists in the name of keeping the people who are content to be average at things. Oh, they may want the numinous and the excellent, but if you ask a preacher to choose between a ‘faithful’ artist vs a ‘troubled’ one, they’re going to plomp for the pious one every time.

Plus, the faithful don’t tend to charge what they’re worth.

Examining 3 Wishes

If you’re bothered by seeing designers scrutinise other designer’s designs explicitly to change them then you might want to check out now. I personally advocate for this practice very hard, since it’s both important to demistify the lie that games spring out of the aether, but I know that some people are both more precious and more sensitive to the idea of ‘idea theft.’ Since I put a ton of my design work out there on this blog, you can probably guess that I don’t have that same fear.

In the simplest sense, what I’m doing here is play. I am playing with this game, with its design. It is more akin to the play of a gear than to the play of an actor, but it is still play.

This is an examination of how a game can give you ideas for another game, it’s not about things the designers ‘should’ have done, or things that they should have presciently known better about.

Onward!

Game Pile: Peggle

This isn’t about Peggle.

Vancian Magic Is For Posh People

In most editions of D&D, there’s this system for magic that treats all magic as a sequence of ‘spells.’ In 3rd edition, the idea was that a wizard would have a certain number of spell ‘slots’ available, and each day they would choose the spells to put in those slots. This is known as Vancian Magic. Contrary to what some folk think, this magic system was not made to be a game system, but it just happens to work really effectively as a game system.

Originally devised by Hugo Award winner and joyous sailboy Jack Vance for his Dying Earth series, this system tends to be tied to spellbooks. The wizard encodes most of a magical spell at the start of the day, using a spellbook to handle all the complex work and memorisation, and completes the magic spell at a later point. It’s an interesting idea, and it sort of feels like electrical engineering played a part in its conception.

Vancian magic tends to be entwined with books. If you look for the phrase ‘fantasy art wizard’ on google, you’ll find that almost all your most prominent hits are going to feature some kind of bookshelf, library, or spellbook. There’s a historical trend for this, of course; in our stories about power, power tends to be about the things we regard as powerful. In the days of history that fantasy wants to use as its framing, books have a power to them, because the people with power were also the people who had books. Often for no related reason.

I’ve talked about this, but it still carries out – these days, intellectuals want to be framed in front of books. People arrange their bookshelves to bear in mind not convenience or access but rather the image of what that bookshelf says about who they are. The gamer of youtube puts himself in front of a bookshelf (a place of power) and fills it with the signs of his gamer power (usually consumable merchandise or purchases that show his good taste).

There’s something else about how Vancian magic travels, though. See, if the wizard does the spell in the spellbook, in the morning, why can they do things later that complete that spell, in a different location? Why does that power move from place to place?

The idea is that power can travel, which may seem weird to bring to attention, but it kind of is because it’s not travelling in anything. The wizard isn’t making potions that have the power and then using them (though they can – and that wizard tends to get called an alchemist). The wizard isn’t putting the magic in something. Is the power in the wizard? That doesn’t seem right either, does it – if the power was in the wizard, why wouldn’t they just call it up on the spot (like sorcerers do).

I think that the magic being able to travel, as the wizard moves, is kind of an unconscious representation of ideas like ether, which you could consider as a kind of pre-internet idea of wifi. It’s not just the idea of a universal binding force, or an energy that flows through everything – I mean, that’s an idea that sounds almost like eastern mysticism when you say it like that, isn’t it? Monks do that! Druids kind of do that. The wizard interacts with it in a way that’s about a triumph of knowledge, of being smart.

Look at the base assumptions of work. Think about why things are chosen to be the way they are. There are often interesting ideas waiting to be considered there.

I Like: The Technical Difficulties’ Citation Needed

I’ve spoken about these lads before. Haven’t I? Surely I have. Anyway,

The technical difficulties are, kind of technically, a podcast, who’ve tried a bunch of formats but all rely on the central game of someone knowing things and the others trying to learn about it. It’s a really interesting, good game, and one I recommend you try with your friends, especially after watching this, because Tom Scott, the host, does an amazing job of keeping everyone on point.

There’s a lot of Citation Needed, it’s very funny, and it’s very approachable, you-can-do-it kind of fun making stuff.

MGP: Children’s Games

Starting January 2016, I made a game or more a month for the whole year. I continued this until 2018, creating a corpus of 39 card or board games, including Looking For Group, Senpai Notice Me, and Dog Bear. Starting in 2019, I wanted to write about this experience, and advice I gained from doing it for you. Articles about the MGP are about that experience, the Monthly Game Project.

Making games for kids is a challenge.

Story Pile: Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego

This show rules.

It used to be when I wrote these articles I felt the need to build up to the verdict as if the purpose of this kind of article is to tell you whether or not you should try it, and that kind of review treats my opinion like a magical trick. There’s a structure to these kinds of things, a meter, there’s position and flow and there’s all this stuff about the science of listener attention, like the way this sentence is starting to sound breathless in your head, and making reviews like that is a kind of game.

It’s a kind of game where the prize is only imagined – I sit back and think to myself boy I bet that person reading this is having a great time and now they’re surprised. It’s a type of structure that I learned from playing games with good arcs, where it was obvious that things started out easy, got harder, and then there was that sharp moment of relief where your expectations and the facts lined up, boom and there we are. Crafting such a review is a puzzle.

These days, I’m not interested in doing that because I’d rather talk about what a series does than whether or not you should check it out. Let’s not, then, spend time talking about whether or not this show is good, and instead make it nice and clear up front.

Where In The World is Carmen Sandiego is a really good adventure story, which uses the format of an educational heist program to tell stories about a cool thief who opposes bad thieves. The main cast features an international conspiracy of criminals, a troublesome anti-criminal organisation that operates outside of Interpol’s laws and a lot of reasons to every episode describe the culture of an area while presenting a villainous plot that is worth thwarting.

Some of these villainous plots, by the way, are just breathtakingly petty. It’s really good Bond-villain stuff, and the whole setting is kind of built around this silly question of where do Bond Villains come from, and what stops them from just being caught?

Then in between these forces of ACME and VILE, you have Carmen Sandiego, who is doing her best to keep a step ahead of the criminals, with her unique knowledge, but who knows she can’t just go to the police with the solution to the problem, because what she opposes, VILE, doesn’t really properly exist.

I think this show is great.

Meta Is Boring

I understand that not everyone partakes of media at the same pace. There are things that, for you, are brand new. Someone out there is experiencing, for the first time, a work that feels like Coyote Gospel, or their first time a webcomic literally leans on the panels of the comic. I know, no matter how much I may feel a thing, it doesn’t make it a universal rule. You are not, in any way, beholden to my tastes.

But god I find meta boring.

‘Meta’ is a memetic shorthand. It isn’t really about postmodern commentary, not really – the kind of people who ‘use meta’ are also the kind of people who dislike the word ‘postmodern’ or who dismiss the idea of postmodernism, often without necessarily understanding the term or its meaning. Meta is a particular kind of wisecracking too-cool, disaffection, and it’s often used in videogames and tabletop games as a sort of get-out clause for failures in their own fiction.

This isn’t to say I don’t like ‘very meta’ works. I after all, really enjoy Portal, which uses its deliberately puzzly structure to talk about how puzzle games work. Meta can be fun. What bothers me, though, is that there’s a lot of modern ‘meta’ work, especially in games, that cares more about using the meta-ness as a get-out clause for the fiction it wants to construct. Indie videogames are rife with videogames that want to draw your attention to the fact you’re playing a videogame…

And it’s so flipping boring.

If your world, if the story you’re telling me, isn’t interesting enough to keep my attention, maybe take it back to the workshop and go for another round or two? I’ve been thinking about this a lot, since I heard of the plot and structure of Glass, the movie, about how it’s a movie that’s mostly about being a screenwriter masquerading as a movie about being a supervillain.

Maybe the story doesn’t need to be clever, per se. Maybe you can learn a lot by making your story fun.

March Shirt: GEN 8 STARTERS!

Woop woop let’s back this up!

If you’ve been following the schedule I’m trying to keep to (and why, why would you do that), you’ll notice I’ve been putting out one shirt design, every month, and I post that shirt late in the month. No real reason to post it late, I just thought ‘eh, sure,’ and put it there arbitarily. That’s why I showcased my Lovin’ Smoochin’ Journey Referencin’ shirt about a week ago.

But last night (for me as I write this), Pokemon Direct showed off the next generation of Pokemon, and showed us three starters and look at that, I did fanart reasonably quickly, and – well, dangit, here we go, three shirt designs. Plus, since they reference Pokemon, there’s a non-zero chance they’ll be gone in a few days, so heck it, here, check them out.

Here are the designs:

And here the design is on our friendly gormless supposedly unisex Redbubble model:

And here’s the design being modelled by the Teepublic ghost:

This design is available on a host of shirts and styles, go check them out! You can get these designs on Redbubble or on Teepublic (Grooky, Scorbunny, Sobble)!

Should go back to the normal schedule next month!

Game Pile: Ghosts Love Candy

I found this game in a skip.