Okay, I’ve burrowed down on some specific points in games. Like how I used Hyrule Warriors to discuss hyperintertextuality, which sucks, or how I’m going to use Skyrim to talk about Rick Astley (that’s a teaser). And I’ve done a bit of a historical thing on Commander Keen 1, based on the video about stimulated recall, and if you get into it, Commander Keen 2 isn’t really a tangibly different game.

If I wanted to explain to you how Commander Keen 2 worked, or what it was doing or its values, I’d have to really pull out the shovels and get into it, to dig deep, to really go out of my way to pick at some seriously tiny nit, and you’d have to be pretty weird, and pretty obssessive about the details in old videogames to care about that kind of thing. I mean, you’d have to be a real dork and isn’t this just overthinking, isn’t this the kind of obssessive detail-oriented comma-fricking that we disdain when people do it of high-faluting fancy academic books and frame-by-frame movie analysese.

Anyway, so I’m going to do that.

In Commander Keen you get a gun. It’s picked up from the surface of Mars, not one of the things Keen makes himself. That’s also where he gets the pogo stick which was maybe some sort of alien artefact they stole from Earth a long while ago, sometime after 1919. Don’t get bogged down in those details. The point is, the gun in Commander Keen is external to the self. The first gun he gets he gets in the first level, and it’s marked with a sign that he can’t read.

In Commander Keen you get a gun. It’s picked up from the surface of Mars, not one of the things Keen makes himself. That’s also where he gets the pogo stick which was maybe some sort of alien artefact they stole from Earth a long while ago, sometime after 1919. Don’t get bogged down in those details. The point is, the gun in Commander Keen is external to the self. The first gun he gets he gets in the first level, and it’s marked with a sign that he can’t read.

This gun is essential to completing the game – there is a final puzzle that cannot be solved without access to the gun. Also along the way, numerous lethal threats can be contained with the gun – enemies that are willing to kill Keen are shot, and stop. Some things won’t stop when shot, and some things are only annoying when they’re un-shot, but basically the gun is framed as a tool for protecting Keen himself.

Keen 1 introduces you to a few instances of a creature called a Vorticon, a jumping pajama-clad kinda-dog-alien that isn’t from Mars. The Vorticons are connected in some nebulous way to the plot to keep Keen stranded on Mars, which didn’t involve just killing him. You thwart their plot, usually shooting the Vorticons, drop an enormous weight on at least one of them, and then make your way home. You find the Vorticon mothership, lurking around Earth, and decide to stop it from destroying Earth.

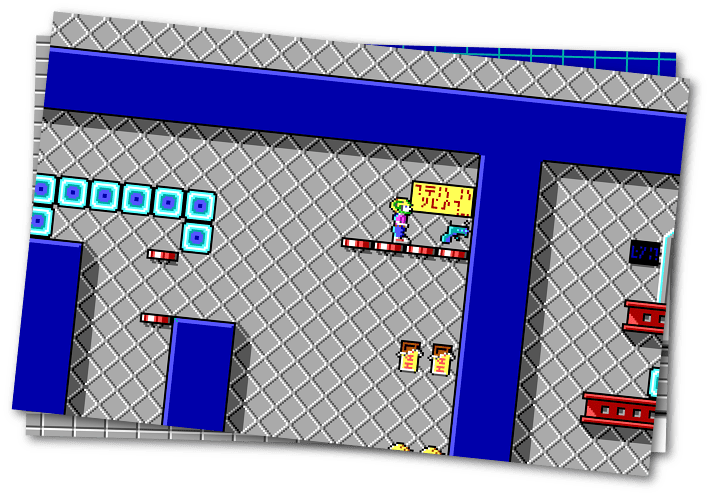

In the mothership, you pick up your next gun, which seems largely the same as the last gun, but stronger – it can now best Vorticons in only one hit – and you’re off. Keen disables the many guns of the mothership and is presented with very few opportunities for a truly pacifist run. While the nature of the game doesn’t make shooting enemies absolutely 100% required, it is definitely necessary for a blind play through, and level design makes any alternative pretty much impossible for playskill levels that doesn’t rely on speedrunning pixel-perfect tricks. This is a game where the gun is essential (for breaking the ship’s plot-critical guns, as gun feeds on gun) and presented as part of solving problems.

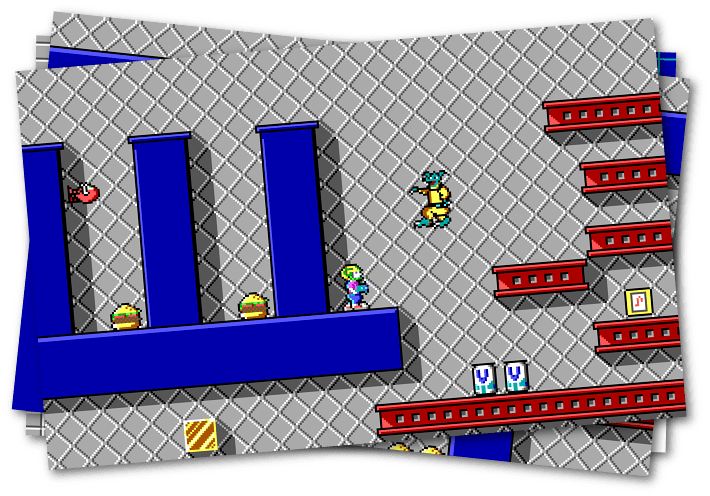

But there is an optional level you can do, where you find, after a long passage that has involved shooting some more Vorticons, a frozen Vorticon. The frozen Vorticon tells you that first of all, the Vorticons are mind controlled at the behest of the Grand Intellect. All of them. Then it asks you not to kill them.

This carries with it two horrifying realisations. First, to proceed through the rest of the game with this knowledge requires knowing that you are killing Vorticons, helpless slaves in their own bodies. That’s bad. That’s a rough challenge for a game that is, at the least, a bit unfair about how it distributes difficulty and spawns sprites in its enormous, chunky, vertical-over horizontal engine. This game isn’t easy, and I haven’t finished it without shooting, despite my time trying.

The other thought is that you’ve killed people! The Vorticons aren’t an alien nothing, the guns you shoot at Mars aren’t knocking people out, the’re killing people, and the killing was done without you necessarily knowing – until you get to that crushed Vorticon. The justification – that they are threatening you and may kill you – is perhaps compelling (and we’re not going to get into the Juul-side idea of how multiple lives interact with the game fiction), but even then that’s not necessary because why is this game about being an 8 year old super scientist featuring something so dark?

It isn’t like the story has any kind of undercurrent like this! It’s not a world full of secretly macabre jokes and references, that came later in the id ouvre. This is a game of Tom Hall’s view of goofy things, of words like Yorp and Garg and featuring Vortoconinja! It’s a sweet, goofy, kids-oriented game with this pitch dark swerve in the middle of it.

And you can not notice it and keep going!

This is an interesting example of what structuralist game examination (the kind Gerard Geanette does) calls hypertext. Text is the work, a participation in the media, then there’s paratext, the zone of media created to experience that media, which includes things like interviews about the work, the box it came in, the way your room changes your perception of the light. There’s also subtext (things in the text implied but not stated), and supertext (things the text says that it has in common with other unrelated works), as well as metatext (the way the text replicates trends in other, related works), and finally, finally we get to hypertext.

Hypertext is the way a text changes when you participate in the same text multiple times. First coined when decribing interactive fiction (like Twine games!) Hypertext is the conceptual space where videogames can thrive. Hypertext is how you can develop a view of a text by iterating over it again. Sometimes this means rewatching a movie with a twist ending, or watching a movie for the thirtieth time and seeing all the technical details in it now you can appreciate them, or maybe it can mean reading a book twice, with a ten year gap in between. The point is, hypertextuality is using the text to examine the text.

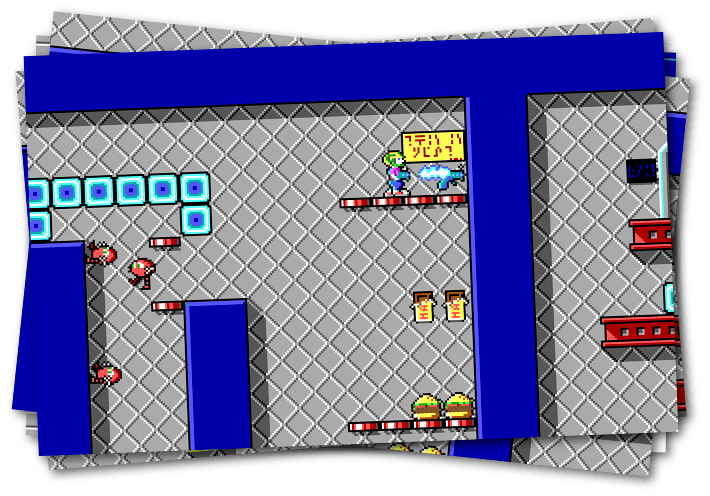

In this case, the first times I finished Commander Keen 2, I never thought about the moral implication of the shooting, because I figured the enemies would get back up. Some of them did. Some were immune. And they were shown falling over, or bouncing and glaring or being surprised at their state. Also, it was a boy’s adventure! There was no need to think about the morality of the violence because the story was more focused on exploration and making that violence relatively low impact. You don’t see blood or violence or injury. Just, well, enemies are zapped.

Once you know about this other point – that the gun works, the gun kills, and nobody you kill in game 2 deserves it – the entire game changes. You can’t not know about it. It was true whether you knew it or not, and the game has no intention of making you feel good about whether or not you engaged with that.

And that is some heavy stuff to drop on an 8 year old!