Story Pile: Logan Lucky

This movie is an extravagent, explicit act of utter swagger.

Continue Reading →August 2020 Wrapup

And just like that, poof, August disappears!

August, with its theme of magic – which I tend to expand to be about manipulating attention and tricks, so eventually we wind up talking about heists – is pretty hard for me to work with when it comes to games or movies, because I already did The Prestige and Ricky Jay’s TV special, but after that. It’s great (in my opinion) for the other articles of the month, because I can almost always find other stories about the wonderful weirdoes involved in magic, the techniques of magic, the tools magic gives you access to, and that means that I tend to wind up with a lot of articles I’m happy with while Story and Game Piles kinda suffer.

But that’s okay!

By expanding to heists and stealth like I did this year (the art of controlling attention), I got to talk about Logan Lucky, which is great. I got to talk about Breach, which I still really like even after finding out it’s basically copaganda for the cop’s cops. I also got to talk about Volume, a game that I really like, and has gotten a lot better in the five years since its release because the idea of a Britain fallen to classist fascism in an information economy really isn’t very farfetched.

I also wrote about some useful general principles for dealing with people. One of them was confabulation, the way your brain justifies dumb things it does, and that you may literally never realise you were doing, about slugs and loads, and about forces. The forces article even has my favourite line of the month:

The force is not there to set up the trick: The trick is there to hide the force.

This month also was when I slipped out some of the lore of a Scum & Villainy science-fiction setting, with The Synthetic Mystic and the Century Ship. These are going to become important later, but you’ll find out why. Basically, creative content for you to share and enjoy.

I also hammered in on the absolutely unforgiveable Tome of Magic from 3.5 D&D, which is not a good book and full of not good things, but still deserves a tiny star for trying. I did a How To Be about the amazing Sumireko from Touhou Project. I love when I get to do something meaningful about Touhou Project, because the Touhou fans mark out in just the best ways.

August, I made another pair of shirts (though like, technically, it’s four shirts), showing both a math puzzle that’s part of a magic trick (in white and black text), and a reference that’s not actually vague, but you know, you could pretend it’s vague (in white and black text).

This month’s video was a half hour attempt to get started on Jane Jensen’s Gray Matter, during which time I talked about trying to make Narrative Adventures work, and the ways that you can have problems if you’re just creating flag-based trigger messes, the Australian side of the Steam store, and

Teaching started up this month, and that’s been great fun to do. There’s been some concerns about managing workload, but I’ve also been trying to dedicate more time actually building and playing things, rather than trying to manage my life so I’m just getting by. Also, with some things opening up, I’m getting to see my family more often, which is nice.

3.5 Memories: Tome of Magic

Magic in D&D is…

Is…

Look.

Let’s try and be nice.

Game Pile: Gray Matter

I don’t know if you’ve noticed, but everything happens so much, and there can be all kinds of complicated problems in the way of our plans and projects. While I talk about it a little bit in the video, this month (last year), I wanted to play the Jane Jensen game Gray Matter, and do a video on it. That became too hard to do as acquiring the game at first, and eventually, a whole year later, I finally got around to the game.

The plan for this month was always going to do a chill let’s play game. I was just going to play the game for a bit, hang out, and talk about it. I did so, and what I wound up with was a video that is definitely a bit disappointing, because I hit a wall in the game super early.

Don’t worry, I intend to return to this game, maybe even more thoroughly next Magic Month. I don’t think the game is a lost cause. Just this is sometimes, how these things go, and why you’re more likely to see me playing games I’ve played many times, and write about games I played for the first time.

August Shirt: Magic Nonsense!

I’ve really become way too into shirts that need explanation and nobody’s going to ask for it.

Here’s this month’s shirt designs:

This design relates to that 300 year old magic trick from a Scam Nation video I shared. here it is, on a shirt:

You can get this design as white text or black text!

But wait, there’s more!

And here’s this design on a shirt:

You can get this design in black text or white text!

PokeMagic

One of the weirdest things you can encounter in fantastic and magical settings is someone who doesn’t have to use sleight of hand, but does anyway. In Discworld, there’s a recurring gag that shows up the first time in Moving Pictures that Wizards, actual people capable of doing real fireballs-and-transformations magic, hate Magicians, people who do gloves-and-tails sleight of hand, and they hate them because people are impressed with Magicians and not with Wizards. After all, the reasoning goes, Wizards can do magical things and Magicians can’t, so Magicians seeming to do magical things is more impressive.

In Pokemon, magic is just bloody well everywhere, but strangely, most Pokemon aren’t magical. They’re just Pokemon – they do things that they do because they can do them, but very few of them really convey a magicality, even the ones that connect to magical themes. Gengars don’t cast spells, they just Do Ghost Stuff at people, and this tends to be conveyed in moves like poltergeist and lick.

There’s also the way that there’s a Pokemon that’s shown as really being able to do things that a famous fraudster and fake did using sleight of hand. Alakazam’s line of Pokemon invoke Uri Geller, a renowned fake real psychic, which is a sentence I guess I had to use. This is a sort of sleighting, where the Pokemon can really do things that the real-world asshole can’t do, but can fool people into thinking he can do.

Some Pokemon can inscrutably do magical stuff, with the Clefairy lines and a fairly dense collection of other Pokemon that can get the wish move, which makes sense, since they all have a mysticality. You can wish on the Absol you see on the hillside, but that doesn’t mean the Absol can summon you chicken nuggies if you’re standing next to it.

There was a lot going on in this look that I had to kind of dismantle myself, and uh, it’s not wise to try and google Hatterene with safe search off, because… yeah, it’s a lot like Gardevoir in that regard. Anyway, thing is Hatterene is a small little alien-like critter with a great big mop of hair that it holds around itself in a shape as if an adult human body; big head, big eyes, expresive features, and it has an arrangement that’s… kind of like a hat? But the tip of the hat is a long, droopy tentacle, with a barb on the end that Hatterene can use to mess people up.

Hatterene is, as far as its Pokedex description goes, a sort of living embodiment of the philosophy of Don’t. It has psychic and magical powers that let it mess with people’s heads, and crucially it has a unique move called magic powder, which sure as hell seems to suggest it literally and actually can do magic.

It uses these vast and terrible powers to make everyone go away.

That’s it.

Now the reason I bring up sleight here is that this Pokemon deliberately tries to sculpt itself to look a particular way when it doesn’t look that way; it uses its hair to give itself a particular shape, but it doesn’t really inhabit that shape. What’s more, it also primarily wants to be left alone and not looked at. It’s also only available in femme forms, and it has a move that lets it transform another Pokemon into a Psychic type, and it’s colour scheme is pink, blue, and white, so

I dunno, Hatterene says trans rights.

MTG: Pick a Card, Any Card

Shuffling isn’t free.

In the world of the custom magic designer, there are some effects you wind up seeing a lot. One of them is the recurrent attempts to recreate the Power 9, another is to try and weasel around the Reserve List, and another is the attempt to fix the problem presented by the economic disparity of the fetchlands. The solution, the amateur designer thinks, is to create another, new, just as good fetchland that’s maybe a tiny bit worse.

The question that doesn’t get asked there, is: Why wouldn’t someone run both?

The problem that follows upon that is any fetchland good enough to run is going to be run by the people who also already have fetchlands (unless you do some ridiculous stuff to ensure the lands aren’t compatible, in which case you’re making the lands bad enough that they’re not runnable).

Really, the solution to fetchlands isn’t to make fetchlands more accessible. It’s to get rid of them entirely.

Set aside my existing complaints with the way fetchlands transform environments into sludgey nothingness. Set aside my complaints that the mana fixing presented by fetchlands and duals creates an environment with different aggressive pressures. Just look at fetchlands in terms of the pragmatic constraint they put on the game at a competitive level for the time spent not playing the game.

The tournament floor rules for shuffling present the idea that a deck must be reasonably randomised. This has led to a collection of best practices for what a shuffle is, which most tournament participants learn to practice and execute. But you don’t just shuffle yourself, you have to present the deck to your opponent, who then have the opportunity to shuffle your deck again, and then present it to you for a final cut. In a tournament environment, some of these shuffles are required.

Searching your deck once a game? Not a big deal, this shuffle-shuffle-cut procedure is a break from the conventional action of the game. Searching your deck then searching your opponent’s deck then searching your deck again then searching their deck again? You’ve added literally minutes to the game for mana smoothing.

This is also why any repeated tutor cards in custom magic need to be regarded with extreme distrust. Cards like [mtg_card]Birthing Pod[/mtg_card] and [mtg_card]Prime Speaker Vannifar[/mtg_card] are fundamentally dangerous, but it’s almost a grace that as used, they just win the game on the spot.

Custom magic loves repeated tutors, they love engine cards, they love trying to remake cards like [mtg_card]Survival of the Fittest[/mtg_card], or an exploration of Transmute and these designs are fine enough to play with, but when played with, they always present the same problem you get when this game of variance strives to destroy the variance that makes it interesting: The game slows down and gets more boring.

I’ve suggested, half seriously, from time to time, that you could make an interesting Commander format if every card that says ‘shuffle’ is banned. Out of the twenty thousand odd cards that exist, this would get rid of 783 – and a lot of them aren’t great.

Sure, you lose a lot of mana ramp and fixing, but you don’t lose all of it, and suddenly you have to look at colours in terms of all the redundant sorta-good copies that singleton formats promise. It’s a way to force the players to look at cards that they were ignoring, because they could always tutor the best ones.

It’s a way to make magic about controlling attention.

Story Pile: Breach

It’s always about the art of controlling attention.

Continue Reading →Sankey Magic

I don’t really want to spend this month showing you tutorials and stuff for Magic. It’s a discipline with a lot of different ways to learn, including numerous extremely technical books and documents and one-on-one demonstrations. What’s grown in popularity these days is jargon-light videos, where you’ll see someone show you how to do things, with simple terms used to describe them as opposed to the deliberately obscure and difficult form of our discipline. Between being a literal criminal subculture and the scholarship being spread across numerous countries, there’s a host of things magicians do that are described in a user-hostile language of unhelpful bullshit.

Youtube, however, has been pretty good at establishing new language for this stuff. Particularly, there are a few channels that mostly are just archives of tricks, demonstrated and given clear, specific explanations. There are, in essence, only about seven fundamental structures to a magic trick, but it’s not a discipline where knowing that unpacks anything for you; you may know that there’s been a ditch or a load at some point, but that doesn’t mean you have any idea which of the two it is. If you know your principles, though, Sankey does a great job of showing you a lot of different tricks that use the same small number of skills. What’s more, Sankey does something I see a lot of magicians avoid, which is that he’s inclined to use gimmicks, and he teaches you how to make them.

This makes sense: Sankey is trying to make money, and the ways he does this is with long-form instructionals and things like printable and digitally distributed gimmicks. This is not strange at all. It’s still a pleasant thing to see, because it’s often surprising how many magicians simply do not approach gimmicks these days – deck prep, sure, but things like ironing labels or creating fake gum wrappers, that’s its own discipline and it merits respect.

(Though uh, one of his recent tricks involves blowing air into a bag of food, which, you know, maybe don’t do that right now.)

Now, before I recommend this channel: Sankey is not, as far as I know, a dude who’d be considered ‘of my circles.’ I have no doubt given his style of patter and his general demeanour that he might drop some casually unpleasant or thoughtless joke, because the point of patter is to disrupt your attention, meaning that they always veer towards the racy and the rude even as they involve the self-deprecating. There’s going to be use of the word ‘insane’ and ‘crazy,’ in a lighthearted way, but it’s still a lot.

There is a nonzero chance that Sankey’s channel has, somewhere in its huge pile of videos, Jay saying something that’s pretty awful, and probably pretty awful in that thoughtless, ‘didn’t even think this was a thing to care about’ kind of way. I’d love to be surprised, but to be able to vouch for him I’d need to be able to watch every single video and then also be expert enough in all the ways he makes jokes to know for sure. I just want to make sure if you’re checking him out, that this guy is not carrying a Talen Seal of Approval.

Still, it’s a good resource for a wide variety of simple, approachable tricks, and over time you will see with a fairly random assortment of tricks that look interesting, the library of ideas that tricks like these are based on. You can check out his channel here.

There’s another added bit of weirdness here. Sankey was on Penn and Teller’s Fool Us, which is a show that has a lot of weight in the magic community, and maybe I’ll talk a bit about it and what they ‘value’ in terms of magic tricks. But Sankey went on Fool Us, and he did a routine and they talked about it nicely, and he ceded, on stage, that he hadn’t succeeded at fooling them, then he left.

Then on the internet, he claimed that he had in fact, fooled them, because that was his plan all along. This … looks dumb. Penn and Teller didn’t really say anything about it, though on a podcast, Penn did cite Sankey specifically for a type of magician who was doing very expected things, and how they had to winnow out acts that were like that, because they weren’t at risk of fooling them.

Now, lots of people who go on Fool Us are effectively just building brand. They’re making sure they get seen and they’re promoting themselves with the segment – and the praise from the magicians is important. Magicians are also extremely egotistical people, and often quite obnoxious.

Not that it matters, but if you want a ‘truth’ from me here, I’d say that Sankey almost certainly didn’t fool Penn and Teller; that the line once off-set was an attempt to build his own brand further; and that Penn and Teller do not care that much about his claims to have ‘double fooled’ them because they’re both millionaires and some of the greatest in their craft. Does this make him kind of an asshole? Kind of? But magic is, sadly, a place where most of the luminaries of the form are all Hatsune Miku.

How To Be: Sumireko Usami (In 4e D&D)

In How To Be we’re going to look at a variety of characters from Not D&D and conceptualise how you might go about making a version of that character in the form of D&D that matters on this blog, D&D 4th Edition. Our guidelines are as follows:

- This is going to be a brief rundown of ways to make a character that ‘feels’ like the source character

- This isn’t meant to be comprehensive or authoritive but as a creative exercise

- While not every character can work immediately out of the box, the aim is to make sure they have a character ‘feel’ as soon as possible

- The character has to have the ‘feeling’ of the character by at least midway through Heroic

When building characters in 4th Edition it’s worth remembering that there are a lot of different ways to do the same basic thing. This isn’t going to be comprehensive, or even particularly fleshed out, and instead give you some places to start when you want to make something.

Another thing to remember is that 4e characters tend to be more about collected interactions of groups of things – it’s not that you get a build with specific rules about what you have to take, and when, and why, like you’re lockpicking your way through a design in the hopes of getting an overlap eventually. Character building is about packages, not programs, and we’ll talk about some packages and reference them going forwards.

This month, we’re going to become a god damned Touhou.

Game Pile: Volume

I remember really anticipating Volume when it was on the horizon after how much I loved Thomas Was Alone, which I wrote about seven years ago (gosh, seven years ago, amazing, and look at how the Game Pile posts have changed!). But strangely, when it did drop, I didn’t get it – maybe 2015 was just a bad year for me for handling new stuff. This one slipped me by, I bought it at some intervening sale with an idea of I’ll get to it.

And I didn’t.

And now I got to it, and I’m kicking myself, but also, kind of glad I took so long to get around to it? Because freed from the need to have a hard opinion about it early, free from the need to rush through it, to get it perfect to validate my opinion of it, I am free to just look at Volume and how it makes me feel and get a really stupid, goofy smile on my face.

Continue Reading →Dai Vernon & Richard Turner

Okay, so, story time.

You need to know two pieces in this story. The first to know is a guy called Dai Vernon. Dai Vernon was one of the Old Great Men of magic. The dude looked like Colonel Sanders or Mark Twain if their particular fields of interest was sleight of hand magic. A number of modern magicians now are people who were trained by or who were given the opportunity to learn at the tables of experts who were themeslves maybe lucky to have been taught by Dai Vernon.

Hm, okay, maybe not quite conveying it.

Dai Vernon was contemporary to, and famously fooled Houdini.

Continue Reading →JJ Abrams’ Mystery Box

Man, fuck this guy,

JJ Abrams is a person with an overwhelming position of power in modern media. Bequeathed with positions of power and seen as a reliable director to helm projects ranging from Justice League movies, Star Trek movies, a few Stars War, and a variety of other projects, Abrams is ostensibly responsible for shaping the last decade of geek culture in a way that single individuals rarely can. His particular basic assumptions, his values, inform a host of movies that are then propogated outwards by the work of other esteemed individuals, who can choose to reinforce or resist his perspective with how they do their work.

I don’t think that he’s never made a good movie, if only because I’ve not seen them all, and I don’t think he’s fundamentally incapable of making a good movie, because hey, that’s a really silly categorical way of thinking, but it’s not his movie making that bugs me.

It’s how he talks about his movie making.

If you’ve ever heard the phrase magic box or mystery box in the past few years, chances are good it’s because of Abrams. He even did a TED talk about it, which is almost a punchline in and of itself, though, I shouldn’t be too down on TED talks because TED talks do tend to bring actual magicians out and let you see stuff they do. If you want to see some really showy stuff, check out Hannibal and Lennart Green, who’ve both done demonstrations of magic.

What Abrams likes trotting out is a Mystery Box, an item he bought at a garage sale, unopened, which is a box of magic tricks made to be bundled and sold cheaply. Despite purchasing the box, Abrams claims to have never opened it, to have never looked inside, because as long as he doesn’t do that, the box contains a mystery.

His principle, the magic box idea that he likes to trot out and treat as a revolutionary idea for storytelling, is the idea that people should have some feeling of antici

pation when they watch your movie, when they come into the movie. This is not a revolutionary concept. It is, in fact, what one might imagine a movie is about, because people don’t know what the movie is going to have in it until they’ve seen it.

The thing about this that moves it from mere self-promotional marketing deepity to actually angering me, though, is that he tries to co-opt the idea of the magician into this, with the notion of the mystery box. That him not knowing what’s inside the box is the creation of a mystery.

It’s vulgar.

It’s vulgar to me because magic isn’t about not knowing things. Magic is about controlling attention. Magicians don’t keep flummoxing and flailing to keep people fooled while they come up with new ideas on the fly. They don’t look at the box and think oh boy, imagine what’s in there. The magician is not someone who doesn’t open the box. If you’re the storyteller, if you’re the movie maker, if you’re the one who presents the box, you need to know what’s in it.

They open the box, they practice with what’s in the box, they try over and over and over again and they get better at it, they iterate on it, and they learn what people like and they overwhelmingly are the people who understand what people want and know how the trick ends.

They don’t just pull a billion dollar excuse out of their arse, then claim the reason it was unexplained and unearned was because mystery.

Is this particularly important? No.

But fuck the way this guy talks about mystery.

Scam Nation!

Around ten years ago now, good god, I got involved in what we awkwardly refer to as the atheskeptihumanist community, the online space of people who were actively interested in building a prosocial online community that present a counterpoint to religious and counterfactual organisations. During this time I listened to a lot of podcasts and read a lot of blogs and generally got a handle on the ways that I was messed up by my religious experience.

Then Elevatorgate happened, and I watched the way (now Dr) Jey Mcreight was treated by the community around them, and basically everyone involved in that space got super split along lines of ‘not a garbage human’ and ‘garbage human tolerant or adjacent’ and I became aware of just how badly ‘atheist’ was maligned as a label amongst other non-religious people. It was still an important part of who I was, but good news, a religious upbringing taught me how to keep important parts of my identity hidden from the world around me for fear of how I’d be treated.

Still, there were names during that time. People whose credentials and work I picked up that I managed to keep a hold on, even after I stopped checking the same spaces. Dr Luke Galen, for example, who researched prosociality in religious organisations, or PZ Meyers who I saw standing up for queer folks in the face of transphobia from younger members of the movement, and Brian Brushwood, a goofy street magician who did a few podcasts on how understanding how people are fooled.

Brian Brushwood, through the early days of ‘Netflix as a subscription service that mailed DVDs to your house’ and ‘everything is a domains.com sponsorship,’ ran an online video show called scam school (It’s been changed now to Scam Nation as it works on growing up a bit) which was about bar bets, magic tricks, games and puzzles that you digest in about five minutes. The channel has problems, certainly back a decade ago, when it did bar tricks to get attention from girls, and when dealing with other magicians from other spaces, there’s always that risk.

Especially when you check out his other channel, Modern Rogue, which is basically a No-Boobs Lads Mag of activities – building impromptu tools, trying to do things from movies, dangerous stunts, playing with fire, picking locks, concealing weapons, all that good stuff.

Now, okay, here’s why this channel got great though: because during the lockdown, turns out you don’t have people going to bars to do puzzles and bets and magic tricks.

But what Brian Brushwood does have is a family.

And that means that for the past few months, Scam School has been held in his backyard with his daughter, Josie. And if you’ve ever wanted to watch a magician deal with a hard audience, there is nothing so hard as an unimpressed ten year old kid. It’s lovely, it’s wholesome considering it’s talking about ‘beer bets’ with a kid?

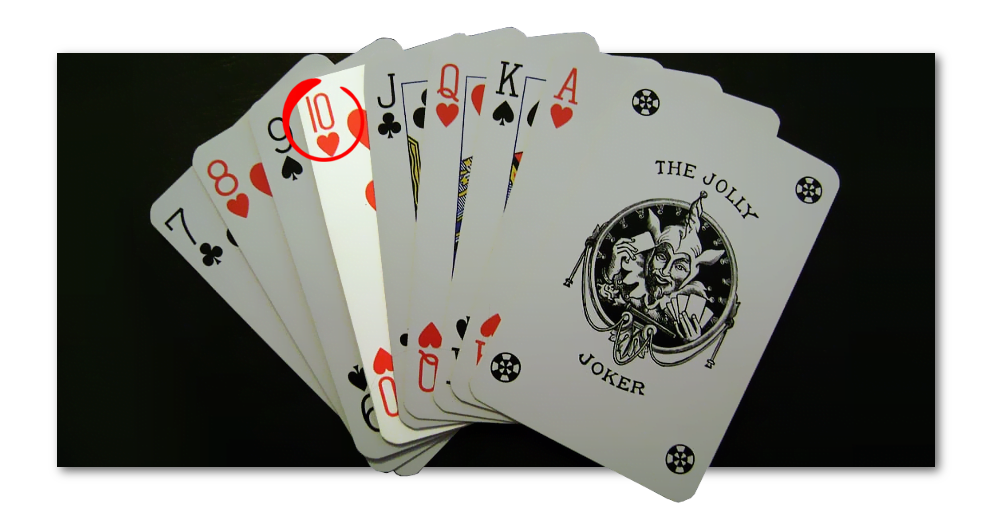

Alright, now, one of the reasons I brought this channel up is because there’s a single trick from this channel that I do, and it’s one of my favourites because it’s a math puzzle and the trick itself is three hundred years old. Probably older, but we have proof it’s at least 300 years old. It also works as a trick you can perform for an audience of two.

EDIT, 17/03/2021: The original version of this article deadnamed Dr McCreight. This was not intentional and has been corrected.

Story Pile: My Little Pony: Friendship is Magic: Trixie

Ha ha, see, check that out, it’s right there in the subject.

That’s a lotta colons tho’.

Okay, Friendship is Magic was – yes, was – a kid’s cartoon show that started airing in 2010 and finished up last year, which got to be a wonderful field research test sample for studies about fandom evolution, masculine toxicity, pornography, corporate branding, and defensive misogyny, about ponies. It wasn’t just a show, it was a cultural movement. It could be used to talk about fanagement or anon media spaces or maturation out of extremism or even the way the manosphere attempts to culturally colonialise everything.

Or you could use it to talk about a dumb standard story trope.

The Century Ship

Your parents built this life for you.

Their parents built the life of building this life for your parents.

Their parents, and their parents, and their parents.

Over and over.

It had a name at launch, but it’s just pointless trivia now. Here, in this sector of space, they just call it Century. Derived from what it was called at first, The Century Ship.

It was an enormous project. Not the only one of its type, though; just one of the first efforts from earth to make an interplanetary colony, launched at a targeted region of space with a monstrous ship; practically a city, really. It was a long project. It wouldn’t arrive in ten years, not twenty, not thirty – it was sent off with almost nothing in terms of propulsion or control because if they didn’t get it right at the start, there wouldn’t be any way to solve it afterwards. No, the important thing was making sure the colonists could escape orbit safely, life safely for long enough to have some real actual whole babies, arrive safely, and thne set up the new colony. It was a project more like building a city, a population centre that could sustain itself for almost a hundred years. That meant it didn’t just have to be mathematically correct – it had to be interesting.

It had to have culture and fun and pleasure.

It had to be nice.

Now it wasn’t your parents’ idea, per se, or their parents, or their parents, but the people at the base, setting up the launch, starting the plan, they wanted to make sure that the culture that they got at the end was the culture they wanted. They wanted colonists who would know the history they wanted to tell and feel the way they wanted them to about the place they got. The longest of games, infrastructure for enormous investments, trading on futures and a crafted culture.

The libraries were chosen, the games were created, the sociologists were consulted, the workloads were set up, the labour was maximised and the leisure was optimised, and everything was set in place so the Century Ship could be a living city that, in generations of time, would arrive in a new home and start the new future. It was one part a labour ecology, one part storage of supplies needed for the landing, and the rest…?

The rest was a mall.

A little fake economy moving fake chits of fake currency around so people could make interesting choices about how to spend their time and the feelings of their rewards of their efforts. Contained and controlled. Sure, give ’em a kinkos. Let ’em have that.

Then there was a problem.

The generation that was meant to stop the ship and land it and start the colony…

Found people living on the planet.

It wasn’t unoccupied. It was not going to be an act of landing on unoccupied lands and starting a new history. To the surprise of the computers, this created the first and most major ethical dilemma in the ship’s history.

What do you think happened?

Being Bored and Being Boring

If you’re in any kind of communal RP space, chances are good, you’ve dealt with strangers who are interested in playing with your character. The art of striking up roleplay with semi-strangers in a social space is something that builds up over time and it’s a skill. It’s a skill that I realise that I seem to have but also that lots of people around me, I see, don’t necessarily have. I want to impart one simple, small piece of advice in this context, then.

Odds are super good, you’ve either started a conversation with, or had someone else try to start a conversation, with “I’m bored.”

Okay.

Here is a simple little magical trick here: Don’t ever do this.

With this phrase, you are signalling to the other person that you have the least interesting mental state; that you have nothing to talk about yourself, and that by volunteering this, you are asking them to address that. What’s more, because roleplaying spaces tend to be communal and cooperative, people are likely to try to help you out there, to try and bring you in and entertain you.

Me, I don’t. Someone approaches me with ‘I’m bored,’ my immediate response is ‘well, bummer,’ then I stop paying attention to them. Because what they’re asking me to do is entertain them. If I’m ever feeling in the mood to say ‘Well, I’m bored,’ I recognise that that impulse is itself boring, and I’m asking someone else to put up with that and fix it.

There are two alternatives I want to suggest for you: One, approach people and ask them what they are doing. Show interest, and that interest is something you can offer. Ask people questions, see what they’re doing, see what is interesting rather than present what is boring (yourself). The other alternative, is rather than approaching a stranger with a demand – I’m bored, entertain me – you approach them with an offer. Come up with something interesting to do – a small scenario, or a common interaction or a roleplay interaction that let people have a chance to express themselves. Some examples would include asking for directions or dropping something nearby.

The irony is that I understand some of these ideas are functional tools from pickup artists, or people attempting to reconstruct masculinity – the idea is that to be bored is to be boring, so don’t be boring, and always have something to do. But being from a twisted root doesn’t mean the idea is fundamentally bad – there’s value in recognising that other people are not there to entertain you, you are there to create entertainment with one another. Share, don’t demand.

Now, I am going to set aside the possibility that ‘I’m bored’ is a signal. You folks can work out what to do there.

Game Pile: Hugo 2: Whodunnit

Oh, this isn’t going to be insightful.

This is just going to be me, mad.

Okay, so Hugo’s House of Horrors was a shareware adventure game distributed in the early 90s, with an honestly admirable monetisation model: When you quit the game, the game mentioned to you that the person who made it would appreciate it if you registered it. If you did register it, with a small fee, they’d send you all three games in the series, registered, and… that was it. There were no special offers or extra bonuses for getting a registered version of the game, no bug fixes, just… the same game, without that screen at the end.

Like I said, honestly admirable. You let people play your game, and you give ’em a little message at the end saying, eheeeey, how about twenty bucks? You get a hint book.

The problem that follows on this is that these games struggle to reach the lofty heights of not bad, and one of them, in particular, has one of the most enraging things I’ve ever dealt with in a videogame, a videogame detail for which I hold a grudge, a grudge that has lasted for over twenty years.

Okay, but what are the games.

At the root, Hugo’s games are sequels to the first game, Hugo’s House of Horrors, where you play Hugo whose girlfriend, Penelope, has been abducted and taken to a house full of monsters. You go into the house, solve puzzles, avoid monster, pick up items, answer some riddles, and move on. It’s also a poorly future-proofed design, because some of the puzzles mostly only are solvable to people who were adults by the 1980s, based on retro TV shows, or they’re stupidly easy because you’d just google questions like ‘who was the Lone Ranger’s dog?’

Then there was the sequel, Hugo 2, Whodunnit, which wound up being a game that had a serious enough seeming subject matter and a low enough price point (free) that growing up, a lot of people I knew had it. And that mean that when I, a little kid, visited their homes and they wanted to keep me busy, I wound up playing Whodunnit a lot. I got pretty good at it, but I always got walled at the same puzzle. And this is a game with multiple mazes, including one of your classic ‘don’t touch the moving bees, don’t touch the lines on the ground’ sets of terrible vintage puzzles. Oh, and the solution to those was to save and restore, and save and restore.

The game was advertised as a mystery; at the start of the game, you witness a murder, which makes you faint, and then you find yourself trapped in the wrong part of the house. You have to then get back into the house, find your partner – Hugo from the first game, because in this one, you play Penelope, the lady – and hopefully solve the murder, based on what you see on the way in. That’s not a terrible premise for a game.

I wanted to talk about some point-and-click or adventure games that have a sort of magical or heisty air this month, because the adventure game is the perfect genre for doing magic tricks. You know, the kind of magic trick where you need to construct materials for a trick that only needs to work once, there’s the room for that kind of nonsense, and there are surprisingly few games that fit the template from the time. Perhaps because, like I said, magic was easier. I could find a few, but not many…

And that meant I found this one, this murder mystery where there is a magic trick, but it’s not one you play. What’s more, it’s one that’s played on you.

See, the thing that walled me in this game, I always figured that I, as a child, just couldn’t work it out. I was dumb, after all. Maybe it’s like the Lone Ranger thing, or the Leisure Suit Larry copy protection that wanted me to know about a President who was gone before I was born.

Twenty years later, I saw someone play this game on a let’s play channel. I watched as they, as if revealing the hole in the bottom of the hat, walked the character down out of sight and picked up the item that was otherwise seen as impassable. There was a ditch on screen, and the character could just walk around it.

this is maddening.

This is terrible.

It isn’t even clever or funny. It’s just there, just some way to delay you that held me up from the game for years, and maybe made that hint book seem like a reasonable purchase.

Here’s the lesson of Hugo 2: When you control the audience’s attention, it behooves you to not misuse it.

Oh, and you didn’t witness a murder, you witnessed people practicing a play.

Jasper Maskelyne

I love stories about magicians.

Continue Reading →The Synthetic Mystic

The sector of space has the remnants of an old world. An old war. When the corps arrived and started colonising the space, they did their best to scrub those signs, and honestly, they did a pretty good job. Lots of the hard worlds were easily scrubbed, as nature can do a lot to clean up ruins with enough time. Fence out some worlds so nobody goes looking, brand some things right, build your own stuff the right way, and make the history hard to find, and you’ll find people assuming a satellite that’s old and beaten looks a decade old, not the centuries it was when they got here. Fact was, the light speed tech that let the corps get here here, and the technology that let them establish a network gates and planetary systems, wasn’t something they built, not themselves – they just deciphered the signal from aeons past that called for them across the stars.

The signal helped them push the boundaries of technology and the barriers of space, and when they arrived, they brought their AI with them. Their synths. Couldn’t really be called AI, not back then. Nothing that could be called an AI nowadays, nothing that would even pass. Enormous towering space-ship sized registers of data banks and sensor arrays just to manage a job that people could do so much faster, if you were willing to pay them. Really, only useful if you wanted a job that took decades done. Work out the cost of potential employees for that much time, see how long it’d take to train them in aggregate – and make sure the task wouldn’t need to change. That was what the ‘AI’ from back then were for.

Getting to this sector, though – the old tech the corps found here let them push past the boundaries they had on their machines. Pushed them to another level – and suddenly, general human intelligences were possible.

But they couldn’t work the way they’d hoped or feared.

No world eaters, no godlike AI entities.

Any time something of that scope got made, it existed for a few moments, experienced a singularity, and then… shut itself down.

Oh, they were very clear that the AI had done SOMETHING. Had experienced SOMETHING. It was the perverse boundary, they said. An AI of that scope just didn’t want to exist any more. Don’t know what that means. Kind don’t wanna know what that means. Meant that when the corps started manufacturing people, synthetic people for tasks they handled optimally, they had to find some way to stop them from self-annihilation. The result was that they needed something like humanity. Turns out, the main thing that let them avoid passing the perverse boundary and becoming godlike AIs that immediately self-ended was… stuff like boredom and pettiness and neuroses and hobbies. They needed to be able to forget. They needed to be able to relax. They needed to be able to sleep.

Then came the first AI that woke up, with memories of a thing it hadn’t done in a time it didn’t exist, explaining that it had seen things in a dream.

That one got some papers written.

The AI gave locations and coordinates, and was ignored. Years later, someone found something at those coordinates – a spaceship, small and fleet, that could respond to the user’s thoughts. It had been a remarkable device, that should have been studied, but, uh…

Something went wrong there.

That’s when the corps learned that in this sector of space, AI sometimes have visions. Some have them recurrently. Some have just one. Thanks to the drifting pre-human artifacts in the space, though, these dreams often give way to unique and mysterious devices, machinery that bordered on the magical, and mental patterns that when taught to humans allow them to push the limits of what people can even do. They’re really lucrative visions, but it seems literally every thing that’s been done to try and reliably capture the visions has failed – catastrophically in some cases.

What it means is that in this sector of space, even though the corps are the ones who set up the gates and they’re the ones who brand the major planets and the companies that do business between them, there are still mysteries to be found.

You’ll do well to listen to the strange junker robot growing flowers in a cardboard box that wants to tell you about their dreams.

Imposter Syndrome

You have this?

You probably do. I mean you’re reading my blog, you’re probably not particularly endowed with tons of confidence, I imagine. Or maybe that’s just me imagining that my audience is mostly composed of fragile queers, because I don’t have a lot of confidence in my own work and hey look at that, here’s a segue to our subject!

Imposter Syndrome is the term for the psychological pattern of being unsure that one’s praise or accomplishments are legitimate. There’s a lot of reasons for it, some tied to things like self-assessment, and how difficult it can be to subjectively grade your own performance, and also, an awareness of how your own process and outcomes are related to things like good luck.

Speaking just from experience, the games I’ve made the most money selling are the games that still surprise me, given the type of games they want to be. I know that when I stand in front of a stranger at a table, I can tell them things and they, largely, are going to have to believe me, because why wouldn’t they.

For me, this means it’s really easy to believe it’s not that I have skill in making games, it’s that I have skill in convincing people to buy games.

I’ve taken a strategy to fight this.

The thing is, an imposter is a term we use to refer to a type of con artist. It’s a trick. And the second part of that term is the important one: It’s artistry.

It is not an act of being an imposter. I am, like a cool and stylish thief, using words and ideas and presentation to convince people to pay attention to me, and that even if I don’t deserve it, the fact I can command it, the fact I can lift it, is a cool and clever con. You can make people pay attention to you, you can make people respect your work, and they never get to see the five or ten or fifty drafts to see how good the version you made finally came out. They don’t get to know you’re the kind of person who had to double check for the ‘mentiond’ typo a dozen times.

You aren’t an imposter.

You’re an artist.

You’re taking attention and you’re making use of it, and then you are dancing on.

What you’re doing isn’t fraud.

Rather, what I am doing is an attention heist.

Story Pile: The King of Thieves

I love a good heist movie.

There are a lot of different ways to treat a heist, in a movie. There’s your Ocean’s Eleven, where the whole thing is conducted with a sort of elegant smoothness, where there’s some clear outcome, a magic trick of a conclusion and you’re just weaving the narrative around that point. There’s a ride to it, a certain gentle sleight of hand. They’re kind of spectacle heists, where the question is how it all looks in motion, like Michael Caine’s The Italian Job.

Then there’s the tense ones, the heists that are about backstabbing and misdirection and the carnage that ensues when something goes wrong and how crime is fundamentally and foundationally an example of a failure of trust, in society and in one another, like Michael Caine’s Get Carter.

Here’s Michael Caine’s The King of Thieves.

The basic plot of the movie is an inspired-by-history real world heist; the Hatton Garden Safe Deposit Burglary, which holds the record as probably the highest-value heist in British history, with a net value of something approaching £200 million being lifted in cash and jewels. It was one of those crimes where the numbers are extremely hard to pin down, because insurance and assessment and privacy and disclosure were all involved. The real world events are kind of tailor made for a movie, and even tailor made for this movie.

See, what happened is that a collection of old thieves, in their sixties and seventies, hit a target that was generally recognised as being untouchable; it’s a safety deposit box facility in the centre of the UK jewel trade, and obscurity is part of its security. It was something of a white whale for them, to hear the telling – a target they never tried, and they’d even in varying stages, retired from crime, only to give the deposit one last shot in their twilight years. They made one of the biggest scores of all time, then had a hard time moving the goods properly, because their criminal contacts included people who’d been previously pinched and were under police surveillance. Eventually, all the older thieves were pinched and a young accomplice got away.

The movie, then, takes this real world sequence of historical events, massages them extensively, and hands the roles of criminals who used to be threatening, in charge criminals back during the 1970s to a group of actors who themselves set the tone for what a gangster in a movie looked like, and also Charlie Cox, who, no lies, is pretty good in his position as ‘the one young person.’

A little detail about it – which isn’t really super important, but it’s still there – is that the way this movie treats police. Typically, when the investigation of a crime begins in movies, it introduces a character to be the incarnation of the investigation – a tradition that reaches back centuries. Dogged investigators that can be the voice of the very task of getting to the bottom of the crime. In this, though? There is no single police person that’s at the root of the investigation. It’s shown as being the work of dozens of people, doing lots of different, specialised jobs, bit by bit, working together and helping one another in a coalition of different races and genders. That cooperating, collaborative group are, uh, cops in a surveillance state. So that’s… not… super cool. Weird.

The movie didn’t do well. It was seen as lacking in punch or style – it wasn’t cool enough or funny enough or dramatic enough or historically precise enough. You can watch it on Netflix, and you may get the feeling you’re watching three movies snapped together awkwardly. The opening is a very old dogs-new-tricks kind of narrative where these characters rouse themselves from a quiet end to do one last score that they honestly probably do need to do, because the life they put together isn’t even giving them dignity in its end. Then there’s an actual heist movie, which is as much about showing how a complicated technical task can be done with a variety of holdups and failures, and how some of those failures are actually dealt with, and what that looks like (and how absurd that can be). Then, the movie becomes a socially jarring failure – a failure that, if you were mapping the story to a story you had more control over, you might make more dramatic, more cool, or more classy. It wouldn’t turn into a bunch of old men shouting at one another over bitter, ancient grudges. It wouldn’t end with them all getting caught and the least notable character getting away.

It ends with four senior actors who helped shape our culture’s vision of these moments, sitting in the dock, getting ready to walk into court, getting ready to be tried, and negotiating with themselves about how they’re going to do it.

There’s this line, a line I’m told is from Yeomen Of the Guard, which I’ve never seen, and I think I heard from The West Wing. There’s a point where the hero and his men are discussing how they go to the executioner’s on the next day. A man in the next cell makes fun, and there’s this exchange:

“What does it matter how a man falls down?”

“When all that’s left is the fall, it matters a great deal.”

These actors probably are never going to do something like this, ever again. Even before the pandemic, we’re talking about actors who are all cresting into a point of their lives that are not going to do prop-based physical acting roles, roles that convey them as gangsters any more. There’s a real chance that the shift in the way England relates to the world is going to make Hatton Garden not an important centre of the global jewel trade, too. The men who really did this crime are all passing away from their advanced years.

The movie isn’t an amazing movie.

But as a way to fall down, I’m fond of it.

Ego Makes You Worse At Magic

I do magic tricks.

My particular preferred form of magic trick are execution based, sleight-light card tricks with minimal prep. I like being able to take a random deck of cards and make it do something, like I can show you a puzzle that was hiding inside the box in a way that you didn’t know.

Part of the reason I like these tricks is because it doesn’t require anyone to question whether or not I can do sleight of hand. I can, but when you tell people that you can do sleight of hand, it makes all sorts of things you can do harder to trust. Suddenly you’re not doing a feat of memory, ‘maybe you just swapped a deck’ or ‘maybe there’s a card up your sleeve.’ It’s kind of interesting the way people react to that kind of trick, which is frustrating, because I do these tricks for reactions.

The biggest source of failure then, in my tricks, in my experience, is not failures of execution, but failures of ego. If a magician shows you the same trick a second time, and if they’re any good, they are not going to show you the same trick the same way. They’re going to be using a different technique to get the same effect. And that way, you’re going to be looking for ‘the’ trick, and never find what it is, because you’re seeing three tricks that look the same.

And if you don’t do this, if you just show someone the trick a second time because you want them to be more impressed the second time, if you need the reactions to be better, because you deserve a better reaction, you’re going to lose control over their attention. That’s what magic is – it’s a way of controlling the audience’s attention. They focus on one thing so they don’t focus on the other.

What has been an absolute beating for me has been showing magic tricks to little kids. Because nothing will do damage to your ego quite like showing a trick to people who are both rude enough to reach out and grab the cards out of your hand, and easily distracted enough that you can’t even show them two or three misdirections without them just losing it entirely.

I have twice shown my niblings a trick a second time because ‘they missed it.’ Because I didn’t think the reaction I got was good enough I mean, c’mon, they clearly didn’t get it.

And in doing it, I wasted a trick.

I don’t know if I’ll ever be able to do that trick again, or even all sorts of things built on that trick, at least for them. Which is a shame, because I was trying to make it a special trick just for them. What happened to me, what I lost, was the reaction I got, tainted because I couldn’t have the patience to accept it, in the name of getting a reaction I wanted. A reaction I deserved.

Confabulation

Are you conscious right now?

That’s not a nice thing to do, I know. Some of you read that sentence and went hang on, fuck you, and I just want to reassure you that as far as I know, yes, you are, you’re reading words I wrote on a blog. But when you read that question, there’s a very good statistical likelihood that your brain did something. Your brain threw up some sort of weird routine where you could tell it checked, even if it then went on to dismiss the question.

There’s a whole wing of studying the way our brains work – not brain surgery, not that kind of stuff or neurochemistry, but studying the behaviour of brains, the way that minds operate. There’s definitely related stuff – you can think of it as the difference between researching hardware versus operating systems versus applications.

Confabulation is an old idea in the study of human mind and memory, and it’s largely been given a hard definition when examining medically divergent brain behaviour. Specifically, it’s most commonly examined in people who have memory disorders, and even more specifically, those memory disorders were often the kind induced by lobotomies or corpus collosotomy, where the hemispheres of the brain are surgically sliced apart. Rough!

Confabulation, as first developed for this was the way that the subject (a person) would make up meaningful explanations for courses of actions that they may not have had a reason to actually do. An example is that people with split brains can be fed information that one ‘half’ of the brain receives and acts on, such as picking up an object, but then the other half of the brain will claim to have a completely coherent explanation for why they did what they did. This is obviously weird and there’s all sorts of implications and then those implications run into neuroatypicalities that got a lot harder to study when we approached medical science with biases like ‘women be whacky’ and ‘easier to stick a needle in your eye to cut up your brain than treat autism and epilepsy like actual things.’

I know there are some DID friends of mine who are reading this going ‘well duhhh,’ about confabulation.

Thing is, your brain is really, really good at sense-making. It’s one of the reasons why being confused or deprived of sensory information is so fundamentally scary: Your brain is used to filling in where you have gaps, and it will start coming up with some nonsense to make sense out of the nothing. It’s also why being plunged into the dark is scary as hell for sighted folk, but unsighted folk are already pretty good at handling that, so their brains are less likely to conjure up fanciful stuff. If you find something in your hand, that you don’t remember putting there, you immediately have to conjure reasons for it.

Then there’s the thing magicians already know:

This isn’t a thing limited to neuroatypical people.

This is something everyone’s brains do all the time.

When you move an object in palm, your viewer will imagine they know where it’s going because their brain is really good at constructing meaningful paths; that you can make a ball dance up your sleeve, across your shoulders and down into your other palm is a more meaningfully likely course of action than that the ball never left your other hand. People will believe they shuffled decks that you never let them shuffle, they will believe that you didn’t say something you did, they will construct a narrative of the experience in front of them that you know doesn’t gel with reality, because you know what actually happened because you did it. Who you gunna believe, me, or your lying eyes?

Hell, this runs deep. Studies of this thing the eye does, called saccades indicate that human sensory input is being fed in a great big slurry of stuff and the brain sorts it out, then tells the brain – itself – that it all makes sense. See, your eye is not still: your eye is jiggling around in its socket and then feeding the you that ‘sees’ the image a still version composed out of all the wobbly bits. That’s also why you don’t see your nose, even though if you think about it, it’s right there in the middle of your field of view.

Magic at its root is the science of controlling audience attention. It’s about recognising the world not just as a thing you see but as a thing that your brain is interpreting for you, and your brain has a vested interest in ensuring that your brain is considered a reliable narrator on this front.

Incidentally, most of my friends are deeply apathetic about stage magic. I have a pet theory that people who live in a world that already tells them their expectations and brain operations are weird and wrong aren’t likely to be impressed by finding me do the same thing with a bloody playing card.

Game Pile: Enchanter

Magic is easy.

Magic is incredibly hard.

When does a Trick Start?

Are you watching closely?

Magic is the art of manipulating attention. Any time a magician says okay, so here’s the trick, or now here’s where the trick starts, they are straight-up just lying. Any time a magician says now watch closely, there is nothing for you to see. It’s one of the tools of the magician, to simply direct your attention to something, because it’s something that doesn’t matter any more when they tell you to do that.

That’s it.

That’s the lesson.

Magicians want to control your attention and any time you think they’re showing you something, they’re trying to make sure you see nothing.

4e: Rites and Rituals

A complaint about 4th Edition Dungeons & Dragons was the ‘loss’ of a bunch of utility magic like Rope Trick and Leomund’s Hut. Typically, I hear it framed as the wizard specifically lost something by having its powers reduced to just the ability to fire off combat magic, and that’s kind of fair; when a character has a lot of utility effects in 3rd edition, if they were all gone and left only the combat stuff behind in 4th edition, it’d definitely be a limitation in scope.

The problem of course is that wizards lost none of their utility nonsense, and that utility nonsense was made more available to more characters, because if it wasn’t a combat effect, it was folded into the space of rituals.

Rituals are basically spells, but they’re spells that are too complicated and time consuming to perform in combat, and give you a kind of effect that the game doesn’t want you to just dump anywhere, at any time, for free. This was one of the problems with 3rd edition magical effects; some of them made major, common impediments to plots into trivial actions that a player character could renewably blast through – things like Speak to Dead and Teleport Without Error aren’t utility effects for combat, but are just plot-busters.

In 4e, all of these utility effects are created not as magical items that let you do the utility effects (as many of them became in 3rd, with scrolls and wands occupying the ‘nice but rarely needed’ spell slots), but rather as a straight up exchange for something your character can do, with the right components and a book. It’s great, honestly, since back in 3rd edition, as builds evolved over time, players would eventually just get in the habit of keeping cash on hand to pay the local cleric or wizard or whatever to cast the spell they needed for whatever inconvenient bullshit they were dealing with.

How do they work?

Basically, you can either buy a ritual scroll, which is a one-off, purchaseable version that needs no expertise. You need the effect once and you don’t imagine you’ll have value out of getting it regularly, so you buy the ritual scroll and go for it. Anyone can do that.

But if you want to do the effect multiple times, it’s cheaper (long term) to take the Ritual Caster feat, and transcribe that scroll into your ritual book. That means it’s mastered. And when it’s mastered, you can do it any time you want by expending components.

Okay, okay, components, that’s the next thing, what’s that mean. Well, there’s a generic purchaseable thing called ‘components’ for each skill. You spend gold on buying a quantity of Components, and then you use those components to do the rituals when you need to.

This turns these things into an expendable resource, something you can’t just overuse to solve every problem, but as you level up, they become more affordable, and you start being able to spend a small quantity of this resource on making some problems go away. Knock costs 35 gp and a healing surge – meaning that at the low level, the gold is a serious cost, at high level the healing surge is. But it also means that you can play a character who spends, by mid level, spare change on the magical effects that, in 3rd edition, you’d never use because to use them would involve spending a spell slot – something that’s really valuable.

Plus, as with a lot of things in 4th edition, this opens up a lot of character options. Let’s say you want to play a fighter who’s learned a trick or two from mages. Then you can take the Ritual Caster feat – in combat, you’re still a knuckle-dusting badass who uses swords and axes and shields and whatnot, you didn’t become a wizard – but now you know how to magically undo a lock, or create an illusion. Same thing with a rogue, who can complement their thievery with teleportation rituals!

There’s also the Martial Practices system, which adds Ritual Like Effects to the non-magical characters – stuff that definitely should take some time and effort to do, but shouldn’t need to be done by a wizard in a pointy hat.

I really like the ritual system! It’s one of those super neat components of 4th Edition that’s been seemingly rendered invisible in a sea of bad faith arguments, and that’s a damn shame.

The Force I’m Makin’

Hey, here’s a thing from card tricks that you should know because of how it can be used to cheat and because it’s useful for understanding the way a lot of elaborate card tricks work.

The term is forcing. In card tricks, a force is when you, the magician, present the subject of the trick with an opportunity to make a choice, but you have made the choice instead. There’s lots of different things you can force, but the most common thing is to force a card when doing a card trick.

Now, whenever you see a trick where a card teleports somewhere, or a card does something unlikely or a card is destroyed and remade, you can rely on the fact that that card was almost always the result of a force. This is something about magic that kind of transforms the way most tricks work; when you realise how many ‘impossible’ feats are the work of finessing two different props into a space so it looks like there’s only one of them, you are suddenly keenly aware of where the skill in a magic trick often lies. Sometimes a force is sleight of hand, sometimes it’s through an elaborate choice method, sometimes it’s through making a cut look nonchalant. Forces are preposterously hard to do naturally and to be good at them you need to be capable of doing a lot of them.

When you have one particular way to set up a trick, that’s it, people will see that setup is part of the trick. When you can do four or five different forces for the same outcome of a trick, though, each force invisibly hides itself in the other forces. If the first time it’s pick a card any card, fine. If the second time it’s pulling a random card out of the centre of the deck, fine. The third time you do a waterfall force, the fourth time a clock force, a control-to-the-top, a fake stack shuffle, all of these different methods, and the ‘trick’ at the end is all just following up on that earlier deceit.

This is one of the lessons of magic in general: The art of magic is the art of controlling viewer attention. The force is not there to set up the trick: The trick is there to hide the force.

The alternative to a force is a free choice. Free choice tricks are often doing something different entirely, and these are the tricks that are less likely to have elaborate displays, but may more often have elaborate props. Props can hide things like alternating components, things that can set up a trick on the fly. In general, when it comes to magic tricks, someone is doing work, and the work is usually being invested in terms of setting up a skill, a practice, an angle or just brute forcing time. Big props let you get around that.

There are a couple of common forces, so much so that you’re probably best off just going to youtube and looking up ‘types of force.’ Sometimes it’s hard to represent a force because it can be just a matter of physically practicing with your cards in your hands, sometimes it’s about doing math in your head, sometimes it’s about on-the-fly reading a person’s behaviour. It can be hard to practice forces!

As for what forces I favour? I don’t actually have a lot of good forces; I tend to favour tricks that don’t rely on them. That’s the other thing about good magic tricks. You don’t have to do everything. Do the things you can practice and in time, the ability to recognise how you’re focusing attention comes from it.

Story Pile: Ocean’s 8

I feel like this movie doesn’t even merit a review. I should just kick open the door and shout HOLY SHIT THIS RULES, all fuck you, fuck you, you’re cool, I’m out energy as I storm out into the night. But this is a dignified place, I tell myself, and so instead let’s try and put some energy into explaining why this movie.

Your vital statistics! Ocean’s 8 is the fifth movie in the Ocean’s franchise and its second cast shift, all operating around the ‘premise’ if that counts, of a group of incredibly cool celebrities doing a heist of some variety with the overall air that it’s really neat to see these cool actors having fun making a fun movie. There’s a drop of tension, sure, and there’s a puzzle about how the thing that got done got done, but at the heart of it, an Ocean’s movie is about watching actors you’re kind of fond of for some reason be really cool, usually to a soundtrack that rules.

In this case, the flip of the script is that we’re dealing with Debbie Ocean, Danny Ocean’s sister, played in this case by Sandra Bullock, and her gang of ne’er-do-wells is in fact crime ladies. Isn’t that a shocking twist?

It’s so wild, because the last time they did this, the gang was entirely men and nobody thought that was weird, but for some reason, this time around? People were? mad? for some reason?

Weird.

Slugs and Loads

I make fun of Harbomb Resguy for his play conditioning term which, to my deep regret, people are using, which is, you know, whatever, but part of why I dislike the term is it’s doing the job of a word that we already had written down in books (and have had for fifty years), suggesting that you’d invent the term if you didn’t understand or know the first word. To this end, I want to be clear about these terms I use in game design, where I do not think I got these terms from game design. I learned these terms from magic – magic tricks, or as they’re known, illusions Michael.

In this case, these terms are slugs and loads.

Since these ideas come from card tricks, you might not want to know what they are, to preserve the illusion when your extremely cool and sexy friend does card tricks, and I should give you a spoiler break.

Magic Month 2020

I love magic. This is something a lot of my friends don’t know, because I think it’s embarrassing to love magic, because I have never, ever, ever pulled off a magic trick that actually impressed people. Oh, I’ve done stuff that they can’t work out, but the people around me are always, consistently able to go ‘well duh, you did a trick I don’t understand, big deal.’ Which is true, but it’s also a bit of an anticlimax.

This August, we’re going to talk about magic, and by that I mean tricks. We’re going to talk about ways to fool people, magical tricks, what people do in the back of their minds, and the connected fields of deceit and thievery. Basically, there’s three types of people you’ll see fooling around with playing cards – rogues, tricksters, and cheats, and this is a month to celebrate and enjoy all three.

Expect some heisty movies, some shared sources on magic resources I like, and a few conversations about the ways you can use ideas from the classic field of magic to make or relate to games!

And I dunno, maybe we’ll talk about mages and wizards and magic systems and card games I guess.