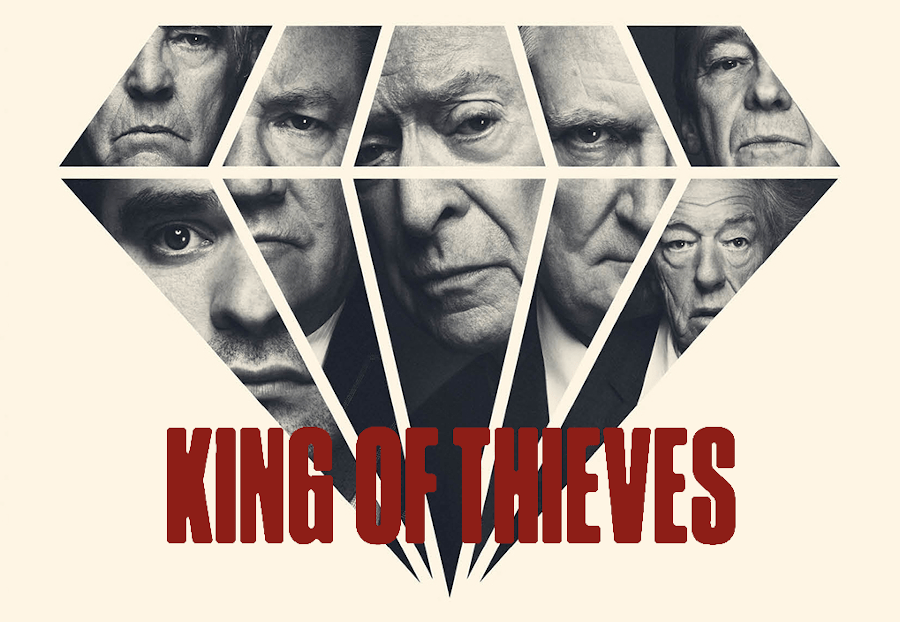

Story Pile: The King of Thieves

I love a good heist movie.

There are a lot of different ways to treat a heist, in a movie. There’s your Ocean’s Eleven, where the whole thing is conducted with a sort of elegant smoothness, where there’s some clear outcome, a magic trick of a conclusion and you’re just weaving the narrative around that point. There’s a ride to it, a certain gentle sleight of hand. They’re kind of spectacle heists, where the question is how it all looks in motion, like Michael Caine’s The Italian Job.

Then there’s the tense ones, the heists that are about backstabbing and misdirection and the carnage that ensues when something goes wrong and how crime is fundamentally and foundationally an example of a failure of trust, in society and in one another, like Michael Caine’s Get Carter.

Here’s Michael Caine’s The King of Thieves.

The basic plot of the movie is an inspired-by-history real world heist; the Hatton Garden Safe Deposit Burglary, which holds the record as probably the highest-value heist in British history, with a net value of something approaching £200 million being lifted in cash and jewels. It was one of those crimes where the numbers are extremely hard to pin down, because insurance and assessment and privacy and disclosure were all involved. The real world events are kind of tailor made for a movie, and even tailor made for this movie.

See, what happened is that a collection of old thieves, in their sixties and seventies, hit a target that was generally recognised as being untouchable; it’s a safety deposit box facility in the centre of the UK jewel trade, and obscurity is part of its security. It was something of a white whale for them, to hear the telling – a target they never tried, and they’d even in varying stages, retired from crime, only to give the deposit one last shot in their twilight years. They made one of the biggest scores of all time, then had a hard time moving the goods properly, because their criminal contacts included people who’d been previously pinched and were under police surveillance. Eventually, all the older thieves were pinched and a young accomplice got away.

The movie, then, takes this real world sequence of historical events, massages them extensively, and hands the roles of criminals who used to be threatening, in charge criminals back during the 1970s to a group of actors who themselves set the tone for what a gangster in a movie looked like, and also Charlie Cox, who, no lies, is pretty good in his position as ‘the one young person.’

A little detail about it – which isn’t really super important, but it’s still there – is that the way this movie treats police. Typically, when the investigation of a crime begins in movies, it introduces a character to be the incarnation of the investigation – a tradition that reaches back centuries. Dogged investigators that can be the voice of the very task of getting to the bottom of the crime. In this, though? There is no single police person that’s at the root of the investigation. It’s shown as being the work of dozens of people, doing lots of different, specialised jobs, bit by bit, working together and helping one another in a coalition of different races and genders. That cooperating, collaborative group are, uh, cops in a surveillance state. So that’s… not… super cool. Weird.

The movie didn’t do well. It was seen as lacking in punch or style – it wasn’t cool enough or funny enough or dramatic enough or historically precise enough. You can watch it on Netflix, and you may get the feeling you’re watching three movies snapped together awkwardly. The opening is a very old dogs-new-tricks kind of narrative where these characters rouse themselves from a quiet end to do one last score that they honestly probably do need to do, because the life they put together isn’t even giving them dignity in its end. Then there’s an actual heist movie, which is as much about showing how a complicated technical task can be done with a variety of holdups and failures, and how some of those failures are actually dealt with, and what that looks like (and how absurd that can be). Then, the movie becomes a socially jarring failure – a failure that, if you were mapping the story to a story you had more control over, you might make more dramatic, more cool, or more classy. It wouldn’t turn into a bunch of old men shouting at one another over bitter, ancient grudges. It wouldn’t end with them all getting caught and the least notable character getting away.

It ends with four senior actors who helped shape our culture’s vision of these moments, sitting in the dock, getting ready to walk into court, getting ready to be tried, and negotiating with themselves about how they’re going to do it.

There’s this line, a line I’m told is from Yeomen Of the Guard, which I’ve never seen, and I think I heard from The West Wing. There’s a point where the hero and his men are discussing how they go to the executioner’s on the next day. A man in the next cell makes fun, and there’s this exchange:

“What does it matter how a man falls down?”

“When all that’s left is the fall, it matters a great deal.”

These actors probably are never going to do something like this, ever again. Even before the pandemic, we’re talking about actors who are all cresting into a point of their lives that are not going to do prop-based physical acting roles, roles that convey them as gangsters any more. There’s a real chance that the shift in the way England relates to the world is going to make Hatton Garden not an important centre of the global jewel trade, too. The men who really did this crime are all passing away from their advanced years.

The movie isn’t an amazing movie.

But as a way to fall down, I’m fond of it.