September Wrapup

Bring out yer alive!

This is our second-last unthemed month of the year, and with it came a scattered arrangement of posts, some that had been written months ago and only came out now, cast off into the far future when I could forget about them. It’s also when I wrote about how to handle money in your game design (and how weird it is that it’s how we handle it in real life, almost like life is an unfair game, odd), about how Elite Beat Agents expresses difficulty, and I put out my article on the charming and interesting Magical Land of Yeld.

This month’s shirt is a pie chart reference to a song! The big shakeup in the store is how I took down some Harry Potter themed merchandise which I once upon a time made as meanspirited jabs at a fandom I wasn’t into, but was willing to sell them, because it didn’t matter if their fandom was bad to me, it was important to them. The thing is, now, selling that stuff can be seen as if I’m okay with JK Rowling’s behaviour, and I’m really not.

This month’s video is another short experiment; an unscripted article on Void Bastards, which took me a very small amount of time to make for a game I’d already pretty much beaten. I quite liked doing this, and I’m hoping it’ll work for some of the other games we’re going to look at going forwards.

This month, I hurt my foot, and that snarled up my grading and that means everything’s been done with not enough time, oh no, oh dear, anyway.

Wasting Waste Space

I can’t believe what a boring bastard of a thought this is.

It is at the time I am writing this, quite late. It’s late not just in the time of night, but also late in the cycle that our house runs on. There’s basically a fortnightly track, and it all orients around the single event of our recycling being done.

We don’t generate much in the way of typical garbage. Most of our waste in this house is paper and plastic, and since we do that, we buy recycleable whenever we can. In our area, in order to encourage recycling, the non-recycleable waste bin is half the size of the recycling bin, which, you know what, whatever.

If you just organically throw things into the recycling as they need it, though, they pack up and fill a lot of space. When things are being delivered in hard cardboard boxes, if you just stick those boxes in, their basic shape exerts force around them. When people give you paper bags instead of plastic ones, and you just ball them up and throw them away like that, they’ll occupy a lot more space than they would otherwise.

This space is at a premium then.

Fox and I basically have to plan throwing out our recycling.

And what’s more, she’s really good at it.

A box has all these points of stress, it creates empty space and it resists being pressured out of that shape. That’s kind of the point of a box. Same is true of plastic containers, though they often deform a little less easily. This means that the most efficient way to put a box in the recycling is to break it down into panels. Larger boxes get cut into matching shapes, then get stacked at the bottom, then soft paper atop that, then crushed plastic and cans, then anything that’s last minute atop it.

The most amazing thing about this is this means that my living room table, where I would normally sit or set up board games, is, amazingly, given over to the task to organising the recycling as we approach the fortnight end, when it will get taken out and go elsewhere. I am trying to make sure that the food I eat now is the stuff from recycleable containers so we don’t have two jars of the same thing in the fridge or cupboard, don’t have doubles of a type of can.

It is an enormous amount of work, and constant mental effort, dedicated to just making sure I don’t have to sheepishly ask our neighbour if I can put some boxes in their recycling (because they’re managing theirs too).

I write about this not because you should feel sorry for me, or even care that much. I’m writing about it to reflect on how something so mundane as ‘chucking things in the recycling’ is now consuming material space and effort to be done in a manageable way in this time of heighened awareness.

Story Pile: Pentagon Wars

Two young fish are swimming along. An older fish swims past them and says ‘hey, kids. the water’s nice today.’ and swims on.

a few minutes later, one of the younger fish looks to the other and says: ‘what’s water?’

Normally there’s a fairly healthy turnaround time on Story Pile posts. I tend to like taking my time on them, and there’s also a sort of queue effect, where a movie or book or tv series will get watched while I do other things, then when I reach the end I’ll spend some time ruminating on my opinion on it before I ever write about it.

This, I watched last night.

CoX: Xixecal

Time to time, I write up an explication of characters I’ve played in RPGs or made for my own purpose. This is an exercise in character building and creative writing, and hopefully interesting.

Not all hells are hot. Oranbegans, for example, knew of a hell that was frozen, an intense jagged land of ice and pain, numbing and biting. It’s the home of the hellfrosts, and shards of that frozen hell extrude through the power of the gods to this world.

We all get our power from somewhere. There’s a title, long since handed down, a title designed to sap even the tiniest power from the name of the beast that wore it once, slumbering deep beneath a trap of ice and water. Nightmares of the old sea, the dark and dreaming deep, all woven together, in the name of the Xixecal.

To most? He’s a frost mage. Nice guy. Knows things. Knows people who know things.

And every spell he casts is sapping the strength of a dreadful beast that can never be permitted to awaken.

Money (in Games)

Money ey.

It’s really useful.

Money is a thing that is useful, because we have our society built around making it useful. The idea of what money is, to a player, is always going to communicate the way money works for us now. It is what you can consider an ideal general utility; No matter what your needs are, you can usually meet those needs with more money.

Now, money can’t buy you happiness, but that’s okay, because we all experience a lot of different problems, and money, sufficient money, can deal with a lot of those problems – it has an overwhelming amount of, like I said, general utility. Converting unwanted resources into money is generally a reliably good idea, because the money will always be able to be put to some meaningful use.

Games use money all the time – letting you convert resources into a single, fungible, generally useful resource. That’s fine, games use resource management all the time, that’s fantastic. What can happen in games – and JRPGs are often going to land in this space – is where you can be confronted by problems where money doesn’t solve the problems, because it’s not supposed to, but your character can still do things that generates fantastic quantities of money that should address problems.

There are three basic ways that the real world keeps money from solving your problem (and why systems of capitalism often involves forcing these problems upon you), which you can use in games to make sure that you avoid the question of ‘why aren’t players solving this problem with their money.’

1. Depletion

There are things that keep us from saving. Rent, fees, transaction fees, costs for upkeep from week to week, like food and fuel and whatnot, those things are all elements that bleed away your money and keep you from saving. In a game, if you want to keep a player from stockpiling money to the point where it’s a problem, you can make large sums of money, or the things that people use their money for, bring with them the upkeep that depletes their reserves.

2. Scarcity

You can make it so anything that the people want to buy is itself inherently scarce. It can be the product of an extremely limited supply, or the end of a slow process, meaning that any that are made are bought very quickly. This can even feel like an infinite wait – players need to wait for keystones to be made craftable, for example, but the expensive components can become more available later in the game. In the real world, there are some products that aren’t reasonably available at any price once they’re all purchased, because the people who have them are refusing to put them onto that free market.

3. Scale

If you’re making a game where players can earn money that compares to buying ammunition, weapons, health packs or storage options, that doesn’t necessarily mean they can stockpile enough cash to buy a house. In the real world, these purchases do not exist on the same scale – and you can absolutely make your game so that the purchases that should deform the way the game works are simply on a different level. Science fiction games for example, set on spaceships, rarely let players earn money on the level of buying candy bars, that also lets you buy spaceships.

Secret Bonus 4: Let Them

You might notice that these existing tools are all kind of dumb, or rely on a world that’s dumb. They rely on a world where you can have this stuff that’s necessary for living that you then have to siphon away just to ensure people don’t get around artificial blockades in their life that you, the storyteller or game designer, are imposing. Why is it that the system we use for exchanging candy bars is also meant to be applied for managing inflexible needs like homes and medical requirements? That’s weird, the two things are simply not similar – should you be able to sell days of your life or your own health to someone for a candy bar? That’s dumb as hell.

I guess what I’m saying is when you think about money in games, and ways to stop money doing dumb things, you have to notice all the ways money does dumb things in the real world, and notice that they only do that because of an imposed system that’s made to benefit some people.

Weird, huh?

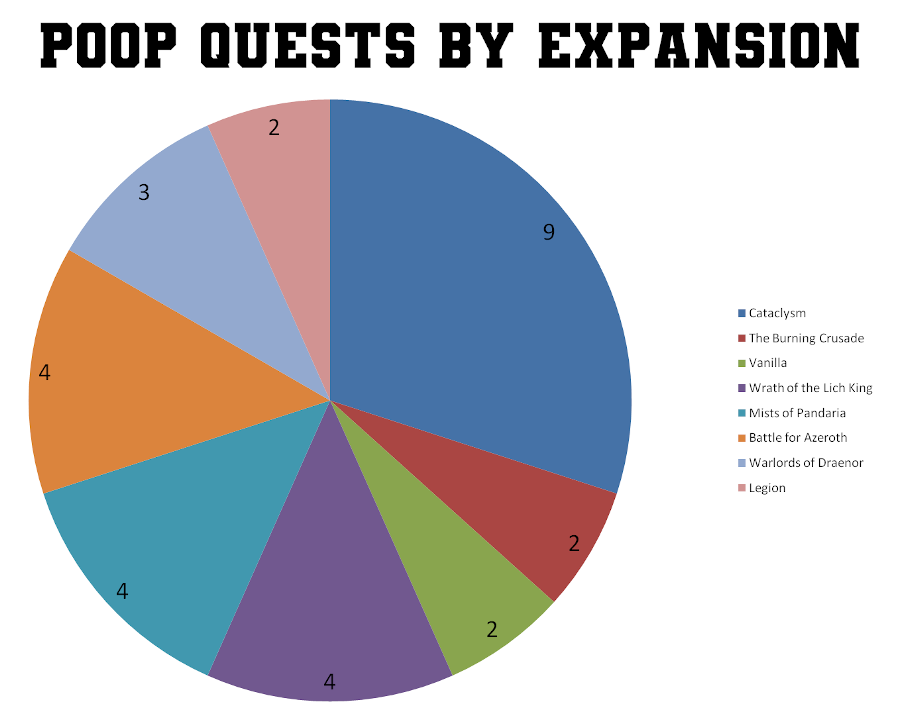

Game Pile: World of Warcraft’s Poop Quests

In World of Warcraft, you can reliably expect that your character has reasonably recently been sent out to the task of handling something’s poo.

World of Warcraft is a videogame, a Massive Multipalyer Online Roleplaying Game that, statistically speaking, if you are reading this, you have played and also, statistically, you are not playing right now. It’s a piece of gaming history and landscape and culture all at once – something that most people involved in videogames and game studies knows about, has opinions on. It is a common metaphor, a Game of Thrones event every time an expansion drops, it is the backround radiation of the MMORPG community discourse, even as it has been outmoded and replaced. Last year, an entire fuss was made about World of Warcraft opening up a service that let you play the game as it was ten years ago, and that ‘behold an old game with less worse stuff’ was a news cycle for months.

But it is also a content platform. People log in to World of Warcraft to spend that day reading stories, or engaging in combat against other players, or accruing resources, or managing crafting or manipulating markets, and all that stuff was different types of content.

There’s this enduring line from Marshall Mcluhan’s Understanding Media that The Medium is the Message. It’s a oft repeated phrase because it sounds kind of meaningless outside of the conversation it’s from, and that can be used as a confusing sort of wedge to force the conversation open. It’s a ramp of a phrase, a line that helps introduce the idea that it needs explaining.

The idea it outlines is that medium is the thing that really changes the world. We talk about the idea of works of art transforming the world, but seldom about how the task of displaying that art transformed the world first. The impact of a painting is hard to compare to the impact of the museum made to house it. Television shows and videogames may be fantastic art, but isn’t the deformation presented by everyone having a TV and then everyone having a phone the greater impact on society at large?

It is in this regard that World of Warcraft, a game, is perhaps best viewed as instead a platform for the delivery of content. There’s a host of different voices and different kinds of content being put into it, and you can extrapolate how those things relate to one another and learn all kinds of things based not on the work of any single piece of content, but rather, the trends of content. How often does this story about a conflict between two parties get interrupted with a greater common interest? How often are two sides presented as equals in the conflict despite one being a slave-keeping colonist and the other the victims of mass mind control? And, as is pertinent here, how often does this game present you with a chance to handle poop?

This was going to be a video.

This was going to be a video, but the project outgrew what I could meaningfully and easily do in ten minutes. It went from being a short little idea that I could present as a series of shots, cutting from quest to quest in the narrative in World of Warcraft. Maybe even play through it, arc to arc, a character progressing from level 1 through to level 120, but that is hundreds of hours. When the idea first occurred to me, I went checking, and found that those blessed folks over on Wowpedia have already noticed this trend, and presented a comprehensive list of those quests. This is not a comprehensive list, per se, though; this is just a set of quests which relate to directly clicking on or moving around poop. There are other quests, such as is presented in Cataclysm‘s Mount Hyjal zone, where one of the quest givers is a magician trapped inside an outhouse, for poop related reasons. This is therefore, not a perfect sampling of poop quests per se, but it’s a good overview.

Some questions then: Are the Poop Quests concentrated? Is there a single place in the story that is particularly poopy? Well, the good news is, we can chart this stuff. Over the years of WoW’s lifespan, there have been poop quests in every expansion, and it’s always more than one.

This is particularly strange, because the nature of an expansion in WoW is when your boundaries and limits and the worst monsters you could fight, in the last expansion, are suddenly outmoded; narratively, there’s some side-eye to it, where you kind of ignore that you hit a level cap and then moved on to another zone where the mundane problems compared to the end-of-expansion problems of your past. Yet in each of these new expansions, in a new time and a new place, you’re introduced to some quest that is literally one of the most mundane, least heroic tasks people do. And it’s always contextualised as somehow worth your time – magic or money are the usual excuses.

But World of Warcraft keeps on bringing you back to sifting through something’s poo.

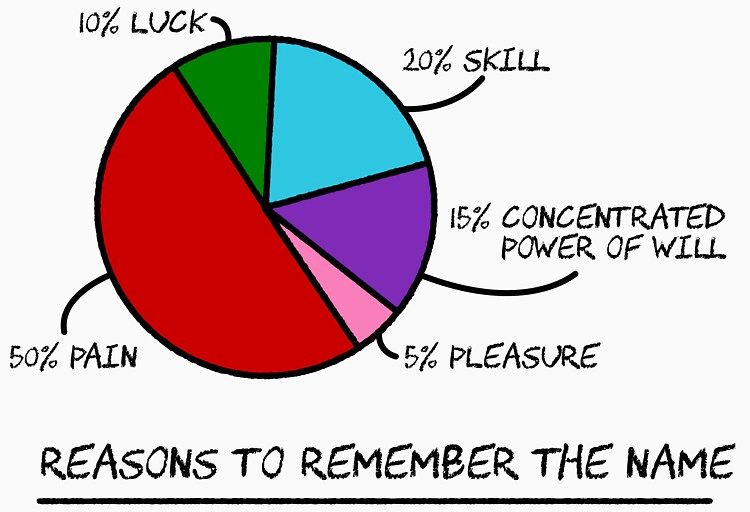

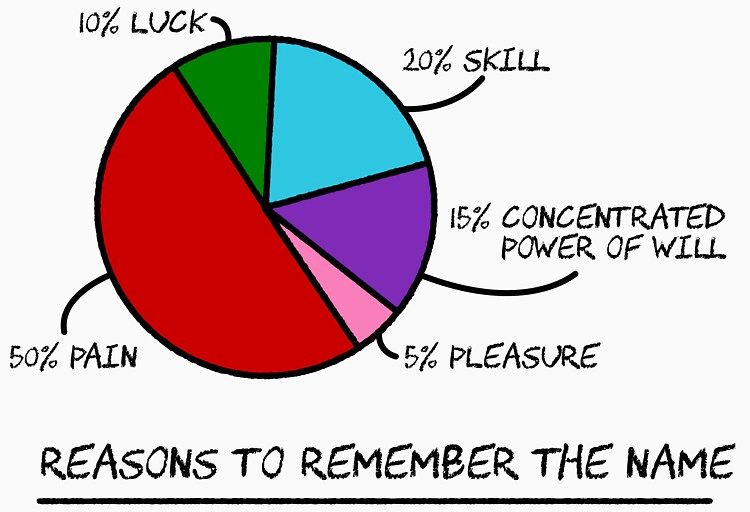

September Shirt: Reasons To Remember

Here’s this month’s shirt designs:

This design relates to a song. You may know the song. If you don’t, don’t worry about it.

You can get this design as black text!

But wait, there’s more!

Diggy Diggy Hole

Alright, so come with me on a journey.

While listening to Power Metal tracks on Youtube, which is definitely a thing a sensible human would do (because ad blockers work on Youtube and not on Spotify), I got treated to this fantastic bit of stompy Power Metal. Most of the bands I like in that genre are either ESL (like Korpiklaani or Sabaton), so there’s always a little bit of odd or weird phrasing, which meant that the actual boast of the song is a little… weird. Right? Diggy Diggy Hole.

Anyway, I liked the song and moved on with my life.

But then I got kinda bothered by the way that phrase sat in the head. Some other lyrics too – lines like suckled on a teat of stone, which isn’t a very natural ‘badass’ phrase you’d see in an English song. Being a context seeker, I figured well, Wind Rose might be an ESL group and this might be one of many Swedish power metal bands playing with dwarf fantasy stereotypes, because power metal bands love personae. And then I found that yes, Wind Rose are ESL – but not because they’re finnoscandian rock-busters.

Because they’re Italian.

Okay then so that seemed weird, ‘dwarf’ and ‘Italian’ don’t leap to mind together the same way, so I went looking further for the origin of this phrase diggy diggy hole.

Which led to a Minecraft Youtube video.

Back in 2011, a Minecraft Youtube channel called Yogscast (I am simplifying and do not care) had someone jokingly chirp the song “I am a dwarf and I’m digging a hole, diggy diggy hole.” It was a bit. It was a throwaway joke.

This being the internet, and a channel with several million internet subscribers, on the famously prolific and fan-productive Youtube, this song was then replicated by dozens of people, and then fans animated it, and then that song was now a song, and eventually, eventually, this found its way to my life.

Because I listen to Power Metal on Youtube.

What’s more, the song is pretty great! It’s got bombast, it’s got some guts behind it, and it sounds like dwarves should sound to me. But also, in this song there’s this one little snippet, one phrase that stands out to me.

We do not fear what lies beneath

We can never dig too deep

Probably the single most iconic phrase of literature that relates to dwarves at all, in any media, is going to be Ian McKellan whispering, The Dwarves delved too greedily and too deep.

And this song says fuck you, Tolkein.

I don’t like Dwarves much. But I do like this song, and I like these dwarves.

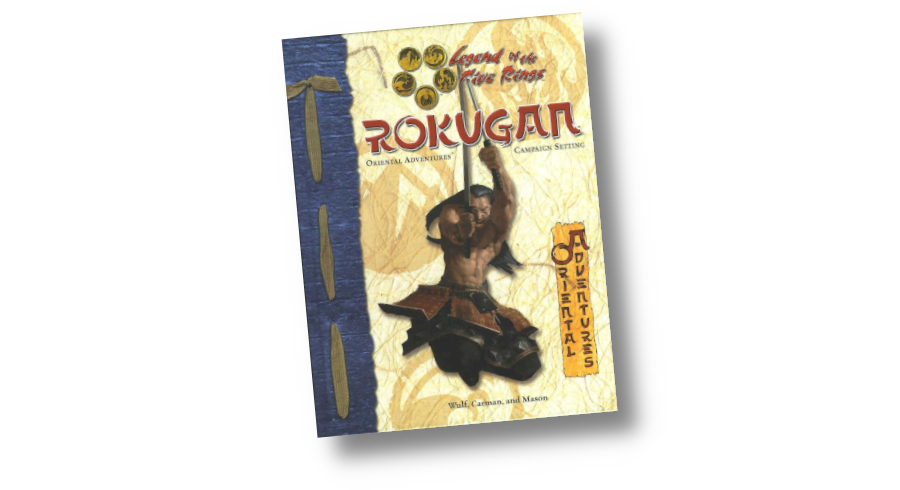

3.5 Memories: Rokugan

Hold up.

I’m going to say some nice things about this book. I’m even going to praise some things this book does. I’m going to recommend you look to this book for examples of how to do a thing and I’m even going to talk about ways this game book set itself apart from an existing, flawed paradigm of D20 design for its period.

Story Pile: Kipo and The Age Of Wonderbeasts

Let’s just have a fun one for once.

How To Be: Tier Halibel (In 4e D&D)

In How To Be we’re going to look at a variety of characters from Not D&D and conceptualise how you might go about making a version of that character in the form of D&D that matters on this blog, D&D 4th Edition. Our guidelines are as follows:

- This is going to be a brief rundown of ways to make a character that ‘feels’ like the source character

- This isn’t meant to be comprehensive or authoritive but as a creative exercise

- While not every character can work immediately out of the box, the aim is to make sure they have a character ‘feel’ as soon as possible

- The character has to have the ‘feeling’ of the character by at least midway through Heroic

When building characters in 4th Edition it’s worth remembering that there are a lot of different ways to do the same basic thing. This isn’t going to be comprehensive, or even particularly fleshed out, and instead give you some places to start when you want to make something.

Another thing to remember is that 4e characters tend to be more about collected interactions of groups of things – it’s not that you get a build with specific rules about what you have to take, and when, and why, like you’re lockpicking your way through a design in the hopes of getting an overlap eventually. Character building is about packages, not programs, and we’ll talk about some packages and reference them going forwards.

This month, we’re going to dive into the world of the dead and look to the Queen of Hueco Mundo by the most powerful shounen anime right, the right of default, the underboob to Matsumoto’s cleavage well, Tier Harribel.

The Tetris of Movies

A few years ago, in June, Rami Ismail brought up, and gently made fun of, the idea of the Tetris of movies. This was a joke, because typically, the conversation that compares movies to games goes the other way around. The cliche is The Citizen Kane of Games, and that comparison is deeply annoying for a host of reasons (for example, film started in 1895, and Citizen Kane came along in 1941, suggesting that the first home videogames still have another twenty years to get around to theirs). Rami pressed B on this question, and flipped the narrative around to look at it from the other side.

What movie did what Tetris did?

Now, I think this question is really interesting, not because I have the right answer to it, but because it does something actually interesting about the comparison between the two possible forms of media. When we talk about The Citizen Kane of Games, it often really means something like the game we’ll all eventually see as important, and that’s so stupid, because it doesn’t even really meaningfully identify what Citizen Kane is. It’s a shibboleth, a reference to the idea of ‘the important one.’

Dumb!

This is a form of intertextual examination. It’s not that it’s bad or even silly to do so – we often use media as tools for examining other media all the time, indeed we even invite it when we reference media within media. Think about how many times you’ve heard Shakespeare’s cliches quoted, or references made to the Bible. There’s nothing wrong about using media you know as a reference point to examine other media you know, and it makes everything easier (Darmok and Jalad at Tanagra, and I can do that now because I’ve finally seen that show!).

I think, if I was going to describe ‘the tetris of movies,’ it reminds me of a few things. Tetris was Soviet-developed; it was revolutionary in its development of gameplay technology, and every game that came after it was, usually, influenced by someone who had played it, or learned techniques from it. That, then, put me in mind of Battleship Potemkin, which was a soviet-made movie that pioneered what we would wind up referring to as montage.

That, however, is just one comparison – a simple one, even. Point of origin and impact on the medium. You might look at it in terms of the influence of the polynimo – is there something so widespread in media of other forms? What about duration? Is there a movie that’s nearly endless in the same way?

It’s a simple little question, and it’s fun because we can talk about movies the way we talk about games.

The only reason we can’t is because we assign idiotic levels of prestige to movies, and our attempts to emulate that prestige is embarrassing.

Game Pile: Void Bastards

This here’s an experiment! This video was made with a strict time limit: Create something in half an hour. This means no script and minimal sound editing. There is one thing about it that bugs me – the game audio wasn’t being recorded and I didn’t check that until it was too late. I like this, and may do a few more like this if it continues to be this easy.

Who Eats Tide Pods?

Remember this?

If you go check out the ‘Tide Pod Controversy’ page on Wikipedia, you’ll find a report that’s long on reports on the meme, full of people talking about the meme, referencing videos that reference the meme, and surprisingly scant on incidents where people, referencing or creating content about the meme actually did the thing the meme is about.

In 2018, there was a fuss. Teenagers, the fuss went, were making videos about the ‘tide pod challenge.’ If you didn’t actually hang out with teenagers, you probably saw tide pods coming up in the context of political cartoons, which used them as a go-to hack’s form of identifying the folly of youth. The idea was that youths were daring one another to eat tide pods, and then, doing so, and we assume, getting hurt and hospitalised.

This demonstrates the kind of object permanence that you can usually rely on media targeted at boomers to do. Because it turns out that if someone makes a video of them putting a tide pod in their mouth, or making soup out of them, that they aren’t necessarily eating that thing after the next cut. The other thing is, we keep statistics about poisonings, so you could just look those things up.

In the United States, an under 20 every single day was hospitalised by tide pods, which made up about a third of all hospitalisations from their ingestion. Of course, that statistic sounds pretty damning about stupid teenagers until you check the data and find that ‘under 20’ could be brought down to under 5s, and that data was from 2012 to 2014. And then if you’re paying attention you go ‘hang on, a third?’ and find out that for every child that eats soap and gets sick, about two elderly people do too.

Tide Pods were already dangerous when they were first introduced. They were dangerous particularly to infants and the undercared for elderly. They still are. There’s a really worthwhile conversation to be had about how the marketing techniques to make Tide Pods generally appealing do make them look like a foodstuff – that we merchandise these things with chemical construction and colour choices to tap into the parts of our brain that like things, and we tend to like things that we can have sex with or eat (sorry, asexuals, but it is a trend in aesthetics). This is really a thing worth addressing in general.

Pathetic, then, that the conversation only surfaced when people wanted to frame it as teenagers, people who we give the tiniest bit of agency and unsupervised time, doing something stupid that, broadly, they didn’t do.

Oh, one final thing.

That statistic up there about how elderly people and children are the primary people who consume Tide Pods? Yes, a child is hospitalised every day under that.

There were six deaths to this kind of poisoning in 2018.

The Difficulty Curve of Elite Beat Agents

I wrote earlier this year about Ouendan, a nintendo DS rhythm game, and mentioned in that article that the game had a western release, in the form of Elite Beat Agents. Elite Beat Agents takes the preposterous idea of Ouendan and reinvents it for a western context. In Ouendan, a wild, roaming gang of school tough cheerleaders find people across all walks of life, including shapeshifting Kaiju and outer space invasion, and help people overcome their problems through the power of cheering. In Elite Beat Agents, this nonsense is replaced by the much more serious idea of an extrajudicial government agency that’s constantly surveillancing the world and deploying suited cheerleaders to fix it.

That doesn’t sound great, hm.

Anyway, in Elite Beat Agents, the game has difficulty settings expressed by what agent you play. Let’s look at that.

First up we have Agent Spin. Spin is brand new to the agency. He has headphones, and clearly listens to music all the time. Spin has the easiest time in this game. It is not difficult for him to cheer people up, his moves are economical, and he gets the same results as every other agent, with much less difficulty than they do. Even his difficulty refers to how easy this is for him: it’s called cruising.

In The Games Black Girls Play, Kyra Gaunt forwards the idea that whiteness needs to see traits of black culture as inherent to black people, rather than the product of practice or skill, particularly in the way that black people are seen as having ‘natural rhythm.’ This rhythm, she notes, ties into singing games, clapping games, skip rope and time keeping techniques that black children do when very young, and share and reinforce in one another all the time, so what is an example of a lifetime of practice is reduced instead to ‘a thing about black people.’

Ostensibly, beating the game with Spin is not impressive: The player needs to do the least to get through the game. This presents the idea that Spin is ‘easy’ but it’s kind of the exact opposite: Spin is the best dancer of the lot, because the player requires the least work to make him excel.

Next up we have J. J is ostensibly an expert in all forms of dance including hiphop and ballet, and that bears out with our principle of work and investment. After all, he can be completely well trained in a lot of official capacities but that doesn’t necessarily mean he lives music the same way, or started at the same age and has the same extensive, ingrained practice that Spin has.

He’s almost as good as Spin! There’s a lot of flourish to his performance, but as Spin shows, it’s unnecessary flourish!

Then we have Chieftan. Now setting aside the awkwardness of a big white southern dude calling himself ‘Chieftan,’ he’s a big guy, and he is the game’s official ‘hard’ mode – the difficulty that starts unlocking things because it’s hard to get through them with this gigantic chunk of Texas Toast under your control.

Chieftan has even more flourish than Spin, and often needs sometimes as much as four times as many points of input as Spin does. This guy needs you to nearly constantly help him. If you slip up and miss a note, you’re probably out of the game entirely, showing he’s extremely sensitive and failure prone – his confidence in his ability to dance is extremely weak.

Then difficulty takes another enormous spike:

With the Elite Beat Divas.

Now, here’s where things get interesting, because the Divas don’t just represent a continuation of the existing difficulty. Part of what makes their levels in the game even harder is that they’re dealing with mostly the same notes as Chieftan, but they’re smaller targets and appear much closer to the window when you need to tap them.

That is to say: They’re doing the same stuff, but being held to a higher standard. This is true for how women are treated in almost all media spaces:

Then the question becomes: How much harder can it be? What’s the next step of difficulty up above that? If we’re suddenly seeing the way women are treated, the way demands are made of women that are already being held to higher standards (I mean, look at the way they dress compared to the men).

Then the next step is to see what happens when you ask a dude to try and meet those standards.

Anyway, thank you for coming to my TED talk.

Inspiration and Privacy

One of the things that drives this blog is a direct pipeline from my day to day experience. Part of what has made scheduling blog posts in advance with a full plan such a great thing for me is that it means that if I have a single incident on one day, that inspires me to write something, that written work isn’t going to happen for weeks or in some times, months, meaning that I get to write about topics over the whole year, then they’ll come together in a particular period, looking like a coherent theme was sought out ahead of time.

It’s neat!

Here’s another thing, though: If I have a schedule it means that, by default, any immediate need to say something can be put on a page, and left alone for two weeks. It gives my thoughts time to breathe, and this becomes very important when I’m talking about things that upset me ore things that I find myself extremely excited about. I have deliberately slowed myself down so I don’t have to be the Hot Take Time Machine, and that means that my opinions don’t get the benefit of riding the Attention Cycle, but they also don’t have me locked into fast, quick impressions of things where I look like a dumbass a year later.

There’s this joke that pretty much all blogs start the same way with this dickbrain, who is a dickbrain, but in this case, the dickbrain is me, and the blog scheduling tool lets me keep a reign on my own dickbrainness.

This means that blogging periods are sometimes symptoms of what was inspiring me a month ago. You’ll see trends and streaks, if you can divine the tea leaves of my me-ness. Complicating this, though, is what my life is doing.

As I write this, I’m coming off a period where some of the things that normally fizz my brain and stimulate my writing aren’t happening. I don’t just mean isolation, though! I mean that normally, university semester means travel, reading, listening and looking at things around the place. What I’ve been left with instead is time spent on private projects – things that involve people who didn’t sign up to become part of my #internet #content #machine.

What follows then for me is a challenge of divining where I can draw a line between what was on my mind and what will seem was on my mind later. What I can’t share, and what I shouldn’t share, and what subjects can be said to be brought up by people in private spaces that aren’t necessarily going to be seen as big ole subtweets.

This is part of the path of managing this kind of writing: it matters enormously to me that if I’m writing something, it’s because it’s something I want to write and because it’s something I think you, the audience, will want to read.

There you go, some process stuff! How it all comes together! As of writing this, back in June, I have already a chunk of writing planning for later months done, some actual articles – and some things that are slowly brewing as I consider if it’s worth going into the topic, or holding back for another time.

Story Pile: Tomb Raider

I know it might have slipped your mind, but there was a Tomb Raider movie in 2018.

… shhh…

ASMR looks fundamentally strange from the outside and I’m reconciled to that.

It’s a creative space which has a lot of what I personally consider gobbledeygook. I mean nothing but the best of intentions to most ASMRtists, but there are quite a lot of reiki healers, both sincere and simulated, Youtube Culture Fans, Beauty Culture fans, Crystal people, healing energies people, conspiracy theorists, and just in general, nonsense that it’s impossible to test for its sincerity, because ASMRt is fundamentally, a quiet and private space where I actively do not want to become heavily invested in the personal life and opinions of these people.

As someone who doesn’t believe in the supernatural and whose opinion of the numinous is decidedly rational, this can be offsetting. Personally, I really like the ASMR space for its tangible effect helping me concentrate as I work. It can be an interesting avenue for science fiction and fantasy narrative, and indeed, good ASMR for me wants to do something surreal to make sure that I’m not thinking of it as ‘serious’ narrative. I definitely like stories told through this format, but I know full well the stories are being delivered in extremely stilted ways.

What I think, though, that matters to me a lot about ASMR, and one of the things I find about it so very comforting is the value that the format puts not just on quiet, but on the ambient and constant sounds of the world around us. I’ve talked about the idea of rhyparyography, the notion of artistic exploration of the unimportant, and how the bulk of videogame art exists in the space of artists making ten thousand mundane bookshelves.

ASMR often is drawn not out of exciting or mysterious devices, or elaborate and unique pieces of specialised hardware (though they are useful for the creation of the content). The things that derive sound for ASMR art are almost always definitively unimportant devices. Clacky keyboards. Tin roofs and rain. Pad and paper. Bottles of makeup and lotion.

As someone who surrounds himself with sound and stimuli, in a field that is so often about the quiet contemplation of the complicated, ASMR It encourages us to listen to ourselves

to our environments

and to the small and mundane devices in our life.

MTG: Otrimi, I Guess?

First things first, you should read this thread by Orion Black. And this other thread by them. You’ve already seen them? Good! Great! I don’t want anyone who is interested in or playing Magic: The Gathering to do so without at least some awareness of this problem, this persistent problem. I guess my main thinking here is that the least I can do is make sure Wizards has the reputation not as ‘one of the good ones’ but as ‘that one has fucked up a lot and needs to fucking address it.’

I haven’t been playing a lot of Magic: The Gathering. Just other things going on, plus any time a banning happens or a new set releases, prices on MODO get a little weird, in a way I don’t appreciate. Typically if I wait a month, all the things I want to play around with get a bit cheaper, and this few months in Magic’s history have been

weird.

The last time I was playing, I was playing, I kid you not, a budget standard Walls deck, using High Alert and Teyo, the Shieldmage. This means that I haven’t really been paying attention for two whole additions to standard, and I also missed the return of Commander – not 1v1 Commander, but Commander – to the MODO interface.

Let’s then talk about a card I’m kinda intrigued to play with in Commander, but can’t see the ways I’m going to make them work:

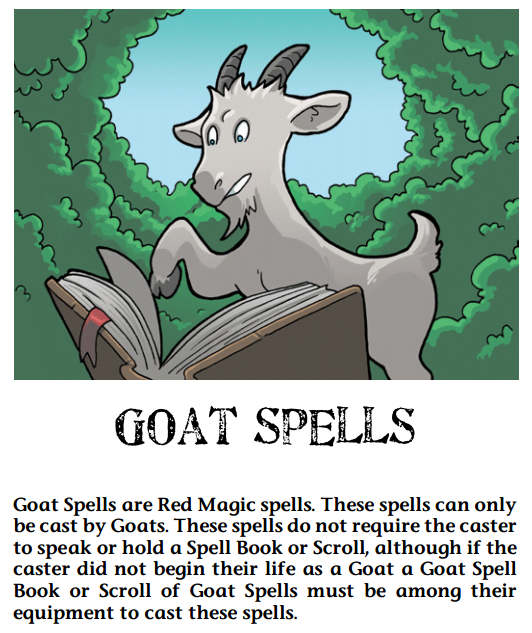

Game Pile: The Magical Land of Yeld

Here is a list of things you are going to find in the book The Magical Land of Yeld.

- A Witch class whose first benefit is literally saying “No one understands me. But that’s fine! I understand myself!”

- A christmas sweater you can give to an enemy at the start of combat and if they’re never attacked, they will become a friend

- Rules for food that improve your dice, including vegan options

- Comics that explain what happens with at least one funny talking dog telling you how to knife a baddy

- Character creation bases that let you pick archetypes such as Princess, Big Sister, Know-It-All, Brat, Dog, and Liar

- Chaining combat mechanics that require you to say ‘excuse me!’ to interrupt monsters

- Death mechanics that let you haunt the baddies until your friends get back to an inn

- A calendar tracking the holidays and festivals your characters will get to experience

- A bunny postman

- A Secret of Mana style job system that starts out basic and expands to Badass

- A spell that lets you summon a horde of sheep

- Beautiful, clean artwork illustrating everything

- A basic adventure where you fight a person who is quite clearly a Messed Up Adult In A Fandom Space Being An Asshole To Kids

- A Sweater Shop

- A Battle Kite

- Fumble systems for spells that lets your existing spell effects work, but also add on interesting disasters

- An extensive discussion of structuring stories in terms of their stages and consequences to build anticipation

- Folding character sheets

- A monster called a bean whale

- And I guess, if I was going to try and convince you to check this book out, it’d be with this:

So go buy it, jeeze.

Continue Reading →I Hurt My Foot

As I write this, I am recovering from having hurt my foot.

I hurt my foot a few days ago. It’s not a particularly big deal but it is a deal. I didn’t drive a nail through it, didn’t need medical attention, didn’t have to cut a portion of it off, didn’t have to walk a long distance on the already-injured foot, I didn’t have to unfold one of my toes and I didn’t have have a piece of earthmoving equipment roll over it, all of which are things that have, previously, happened to my foot.

My response to it the first day was to not really pay attention to it, and then it became unbearable and impossible to sleep with; the result was the next day, I had to stay at home and not do a grocery shop because my foot was hurt so badly and the pain had been exacerbated by my inattention. I sat on the sofa and watched Netflix and generally felt like a bit of a lump. Nothing in the queue got done that day. I was desperate to recover, because the next day (today, as I write this) I had to teach and I didn’t want to let my students down.

This worked, I got a full night’s sleep, I taught all day, and then, because my foot felt so much better, I thoughtlessly flicked it out to stretch it, and immediately regretted my actions.

Now, through all this, I made my situation worse by consistently forgetting that painkillers are a thing; what’s more, these painkillers are anti-inflammatory, which means I forgot things that wouldn’t just help me immediately but also makes the process of recovery better and easier.

It’s just a bit of friction. I need to remember how long it’s been since I had one, then I need to negotiate with myself if I really need it, if the immediate pain is that bad.

This isn’t an interesting blog post, and as it goes up, I’ll probably be fine?

But I kinda use this blog for diary notes, and during the pandemic, being aware of my own dumbass behaviour that makes it harder to do things is important. Productivity is being diminished by every form of friction imaginable, after all.

BDG’s Commedia Del Anime Chart

Hey, did you like this video?

I liked it. I liked it and it gave me a list that was useful as a way to consider collections of characters (like roleplaying characters, or the cast of a book you’re working on), and that seemed a fun thing to play with. Problem is, the complicated system that BDG outlined here isn’t presented with something like a spreadsheet to copy and fill in on your own.

Sooo

I did that.

Here’s a link to a viewable chart, which you can Make a Copy of and fill in with your own characters. Have fun!

Top Five Pokemon Gym Leaders That Show This Game Is Incomprehensible For People Over Five

Pokemon, a game franchise for children, is a well-loved cultural fixture that we all share in as a group, has a recurrent feature of gyms. Gyms in the game are sort of like little tests that block your forward progress until you overcome the challenge they present, then they give you a signifier that you’ve beaten them so as a player, you can track which ones you’ve successfully beaten.

These gyms are also presented, in-universe, as a place that you, the player character are going to, and are set up with an actual person in charge of them, the Gym Leader. Presented then here are five of those Gym Leaders, in a list.

Continue Reading →Story Pile: Coconut Telegraph

Sure, we’re bumping at the edges of the month, but trust me: There’s no Jimmy Buffett album that’s got anything fun to say on Pride Month. And this is going to be the last of our Boats to Build articles – at least unless I really regret it and extend my examination one extra album, for later.

The albums of Jimmy’s I listened to were the albums my dad’s music collection; the records he owned, on vinyl, and when we moved and I grew up, they were just there. In the church environment, dad couldn’t readily add music to his collection – certainly not vinyl, with his new fangled, impressive CD player that lived in the corner of the living room like a big black box of impressive technical doom.

I try not to think too much about it. Dad didn’t buy more Jimmy Buffet albums after this one – and this album landed smack between my sister’s birth, and mine. It might be that dad felt there was a massive dip between this album and the next… or maybe, being a father of two and looking for work that could support that while trying to contribute to church meant that these were the first costs that got cut.

In a way this selection of albums that all predate my birth but were endlessly replayed as I grew up are part of the foundation of who I am, a reminder that no matter how millenial I am, I’m grappling with being a product of cultures of lies that give me conflicting, meaningless insights into who they think people can be. It’s up to me to pull these pieces together – or discarding them! – and seeing what I can find.

This album has both one of my favourite Jimmy songs, and one of my least liked Jimmy songs.

Five More Bleach Songs That Were At The Start Of Episodes

I’ve said Tite Kubo is an artist who expertly renders a few seconds at a time. It means that when you ask him to try and create a splash page you’re going to get characters full of personality and aesthetic expression and maybe you’ll even get a vague hint of how those characters are strange to one another.

Ask him to resolve a plot and you’re going to get something that feels it got punched out of a template. And honestly, good. I don’t think he should have to try and pull of what he can’t do.

Know where this guy’s abilities excel?

They excel in media forms where you can depict maybe a split second of motion, a sense of character without necessary dialogue and maybe a single phrase or background image. Bleach is an entire anime universe constructed for AMVs, and you can tell, because of the opening and endings that already basically are.

I’ve already spoken about Shojo S, Asterisk, Alones, and Houki Boushi last time I did this, but the good news is that Bleach had forty five openings and endings, split unevently between either, so it’s not like I’m running out of material for this any time soon. I did do a stupid thing by mentioning Houki Boushi first because that ending kills and there are also thirteen versions of the ending, and if I put together a list of ‘all of the Bleach songs in order of best to worst’ Houki Boshi would fill an embarassingly high number of the top twenty.

Here then are another five.

5. D-tecnoLife

If you ever needed another testament to the complete cluelessness of this series, of the not knowing anything at all about what it was going to be, but being very sure about the methodologies of the story, behold the second opening. The song here is about being sad and tormented, but refusing to give up. It kind of frames the story it’s showing you as about a quest to go rescue Rukia as you fell into this world of strange and extremely cool characters who you are at odds with (but look how hot they are except the big fat one and weird puppet dude).

What we see is a montage of characters who are of varying importance to the plot overall (I mean, hi Chad, sorry Chad, hi Ganju, goodbye forever Ganju, jesus christ), but it still introduced you to a large chunk of the Gotei 13 characters that you wanted to know about. It didn’t do much to tell you about who they really were, but you did get some hints – like the way the opening shows you Hitsugaya dealing with being under Generic Attack from Ishida before trying to kill you, the viewer. I liked the way it showed a connection between Soi Fon and Yoruichi, with Soi Fon just trying to take Chad’s head off and Yoruichi wrecking her by taking the tip of her sword.

Which.

When you remember that sword is Soi Fon’s soul

And

You know what, let’s move on.

4. Tonight, Tonight, Tonight

A filler arc would normally be a perfect place to drop a mediocre opening, and you can sort of notice the way this opening saves its budget by using reused footage, still images, slow pans, empty spectacle, and an annoying focus on the god damn puppets. It also shows off a collection of Bounts, which are like slightly paper-jammed photocopies of designs you’ve kind of seen before elsewhere in the series.

This opening also has the bumper framing of Rukia jolting Ichigo into motion and then being his point of rest, at a picnic, together, where they fall asleep, because they are Good Friends, and Not Romantic Partners.

Man this series had no clue where it was trying to go.

Still, this is kind of how I feel like Anime Openings want to be, with this sort of smash-cut sequences of one or two actual things that happen in this story that are important to the story, and a chunk of character expression in a few short heartbeats. What really sets it apart is this song, by the Beat Crusaders fucking rules.

Apparently Phil Collins covered it at some point? Weird.

3. Rolling Star

The story is still in filler space, and that kind of shows in the way this opening shows you all the top-polling characters and almost nothing of the enemies this story is about dealing with – they’re represented just by bleak shadows and shimmering shapes. There’s some hint of Gin (remember Gin?), Aizen, and Hollow Ichigo, but make no mistake, this opening was rolled out while theywere still in the filler turf of the Bount arc. The opening is a sort of ‘hey, remember the cool stuff?’ that you could use in a filler spot to get people to look forward to the thing you’re definitely not giving them yet.

It does mean you get a sort of platonic ideal of Bleach at this point; cool characters in casual gear, looking great (I mean, how cool is Hitsugaya’s outfit here), and lots of symbolism and imagery that absolutely does not and will not happen as suggested, but crucially, which kinda feels like it would.

That’s the thing that honestly feels like the biggest cheat: The story presented in this opening is a story I want to see more of, and we don’t even get that.

Complicating this further is that the song is excellent, a sort of ascending punch to Houki Boshi‘s crashing descent.

2. Velonica

Mmm, can you taste that declining budget?

This opening is composed of a large number of still shots and the animation is stuff like dramatic fluttering of robes, which is one of the easiest kinds of animations to do. You don’t have to track the movement of the objects, you don’t have to be sure that they make sense in a single shot, because what matters is that they look about right in aggregate. There’s a lot to forgive in reusing frames, too!

The opening is also a testament to how this series just has no earthly clue about what, in it, is going to be important. It does spare a moment to give you a massive shot of Nemu’s thigh, which is something, I suppose, but there’s this direct flow from Unohana into Kenpachi – and imagine if you’d known ahead of time that those characters had literally anything to do with one another.

The song kicks ass, which is why it’s in this list, but it’s a symptom of how this show has no idea of where it’s going or what matters. There’s a suite of characters presented at the end, who, by the way, rule, and their character designs are great, expressed in that single last moment, but that’s all you get. More time is spent focusing on Ginryusai’s bloody eyebrows.

1. chAngE

First of all, I think this song rules, I like it a lot.

I also think that this opening is a sign of just how utterly far Bleach has come from having the faintest clue about what it was going to be about or where the story was going, and this came with the knowledge there were two more plot arcs and seventy episodes remaining for the show.

The opening is full of these wonderful signs of stylistically rendered completely confusing nothing. Why are we seeing Ichigo flying in a trenchcoat against a sky of crows? Why are we seeing it in these long paced out sections? Why did Orihime say change?

By the way, this is one of those things Bleach does to its immense detriment: Orihime and Rukia both get Kairi’d real hard. They’re characters with nothing to do but to sit still and be emperilled so the plot can advance up to them, and that’s it, it doesn’t change the nature of what’s going to happen when the rest of the heroes get there. Also, note that because Orihime was the one being Kairi’d most recently at the end of the story, she’s the one who wound up ‘winning’ Ichigo, despite having three other potential love interests, two of whom were women. You’ve heard of ‘First Girl Wins?’ This is the sadder defaulting finale of that, a sort of musical chairs of Wrap It Up when the budget runs out.

Then, you get a glimpse of what’s going to happen next: Ulquiorra and Ichigo are going to fight and Ulqiorra’s going to look awesome. And

that’s all this vision of the future can give you.

The Vizard are in this! They look cool! They have cool masks and personality! Just show us them flipping out!

Compare this to the opening of the Soul Society arc; you got glimpses of characters, there was action, they were shown interacting, there were hints of who they would be even if the anime wasn’t sure. Characters were shown expressing the way they would be in potential spaces. Song’s great, no lies, but it’s an example of how Bleach wound up being: Impressively crafted, clueless nothing.

4e D&D: Marks Are Great

A common criticism of 4th Edition D&D is that at its root, it was good at combat, and therefore, everything in the game, is in service of those combat rules. One example given, is that in 4th edition D&D, there’s the mark system, which turns any kind of player choices manipulating enemy behaviour is turned into a simple reliable mechanic and the player doesn’t need to think about it to engage it, and that this is bad.

This is of course, a stupid position because I introduced it up front so I could get you on my side with a comical twist. Of course I think marks are good, and that’s in part because I think the first half of that argument is kinda a bad faith argument. If you think 4th edition D&D is only combat mechanics, it tends to suggest you haven’t really cracked the books. I could talk about how the nature of the game is that good guides for the creation of narrative don’t need lots of space, and convenient reference text for combat entities does, and we’re back at talking about rainbow tables and storage versus process, but whatever.

The mark system in 4th edition D&D is a blatantly tactical gameplay mechanic.

And I love it.

If you’re not familiar, marks are a system that all the characters with the classification ‘defender’ – you might know it as ‘tank’ or ‘blocker’ or ‘guardian’ – get some ability or other that lets them impose the status of marked on enemies. Marks have a few standard rules; specifically, when you have the marked status, the person who did mark you matters. When you’re marked, you suffer a -2 penalty to attack rolls on attacks that do not include the thing marking you. That’s it, at base.

This system is implemented in a lot of different ways; Wardens can mark everyone around them as a free action, but they have to choose when in their turn they do it, which can make for some tactical choices about where and how you position yourself. Fighters mark everyone they attack, whether or not they hit, which means they care about doing lots of incidental attacks, and view area effect or multi-target attacks as a form of control. Paladins have two different marks – one which happens on specific attacks, and one which requires them to remain near the subject. There are more of course, but just these three examples present the mark as a tool where the player can treat the battlefield in terms of their impact on it; monsters have a reason to want to avoid them, and they have a way of controlling monster behaviour. Marks don’t stack – the most recent mark over-writes the other ones.

It’s not just the defenders who can use marks themselves – because it’s a standard mechanic, you can then have other characters use them. For example, you can make a fragile character get a risky power that marks an enemy, which means that suddenly, you’re a high priority target and it makes it harder for the tank to keep that enemy on them. Another option is a support character who can make another character mark something – so you could play a psion, that says ‘hey, enemy, you are now marked by the tank.’ These are interesting options. And you can even use it on enemies – Sometimes a skeleton warrior may have the rules text ‘Deals 1d8+5 damage, and the target is marked.’ And that right there is a simple mechanic that suggests that the enemy is doing what it can to try and force you to focus on it.

Now why are they considered bad?

The idea seems to be that if marks just work, players don’t have to work to roleplay their characters being visibly fearsome or expressing themselves in the world around them so the DM will make monsters behave in a way players want to manipulate. That’s something that sounds compelling if you are, like me, an amazing roleplayer who’s great at commanding attention and capable of convincing DMs. But there are lots of players who want to play a showy, ostentatious asshole of a tank who isn’t actually that great at one-liners or showy, ostentatious violence in description.

This is a false idea, in my opinion. The whole point of Marks as a system is that it’s designed to make something in the game that should work work reliably, rather than make it prone to the whims of the player. It’s not as interesting if your character can or can’t maintain enemy attention based on your ability to say something rude or shocking or clever in another language, but it is interesting if you’re able to make choices about where you stand and what targets you care about.

It’s also something about being in fights. If you’ve never been in a fight, it might surprise you to know that there are ways to fight that make ‘disengaging’ from the fight actually hard, and it’s not because you can make fun of people, it’s because of stances and reach and position.

I think Marks are great, and part of why they’re great is because they reduce the friction of what the game play is directing to not determine whether or not a thing can happen, but rather the game rules dictate what will happen, and it’s up to you, the player, to explain how it happens.

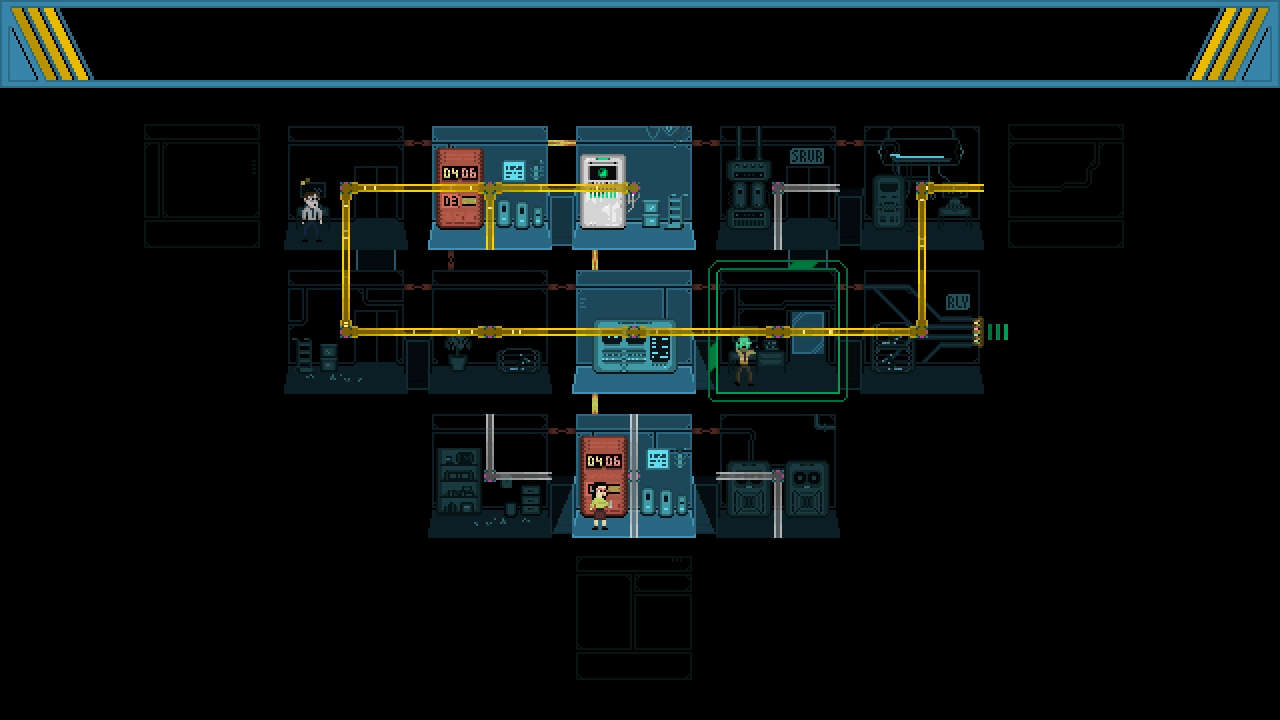

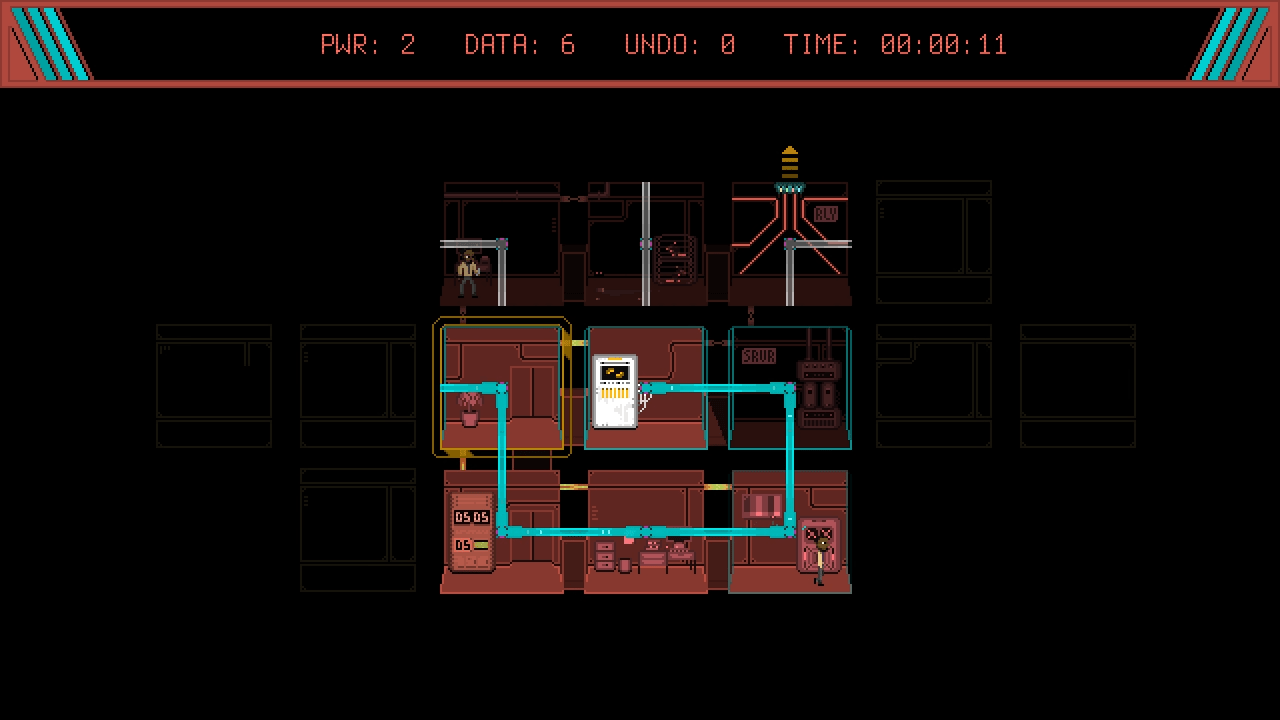

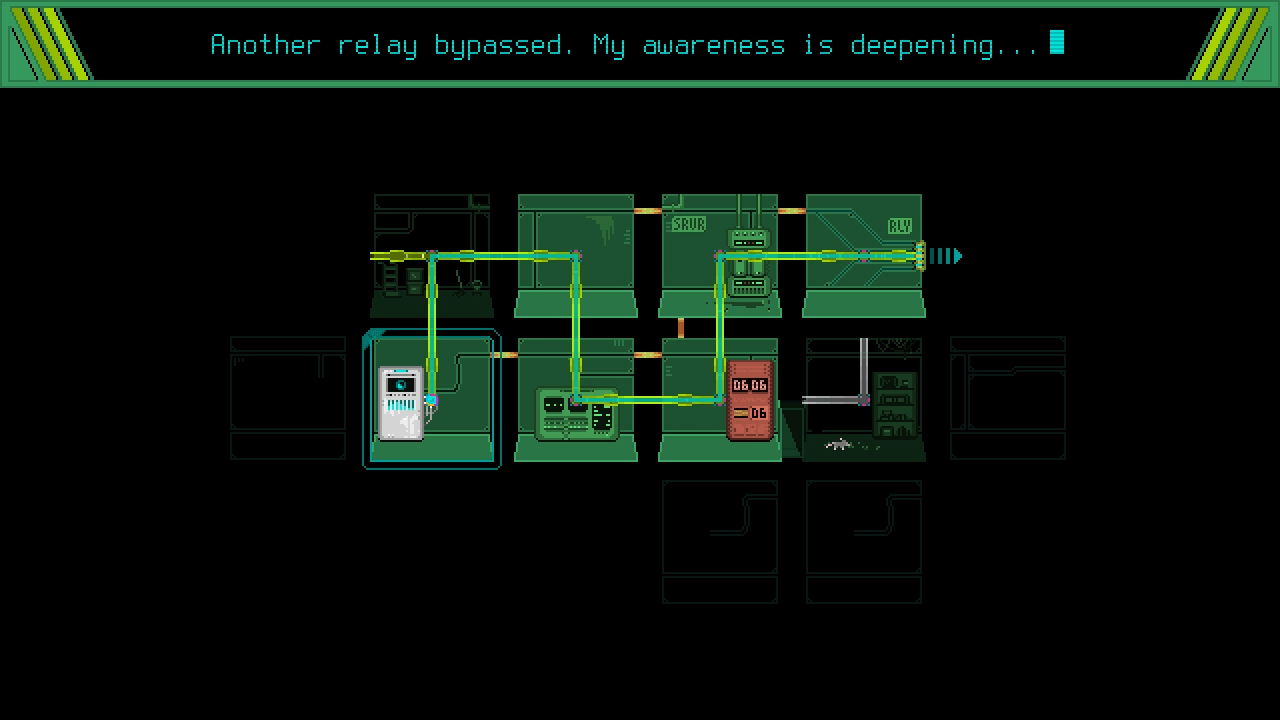

Game Pile: Bit Rat Singularity

I have, in my time, played a lot of Pipe Dream.

It’s got other names. Runoff was one I played a lot in the MS Dos game days. There was also Oil Spill and Lava Flow. It became a Windows title, and had names like Pipe Mania or Pipes! and related games like Laser Squad, the same sort of general construction puzzle game where you had a source to flow from and you had to construct from that source to achieve some end. Usually, these games were timer based, sometimes they were limited components based. Perhaps most famously, Bioshock used the Pipe Dream mechanics to represent their hacking mini games.

These types of games are in my mind as path constructors. And you know, they’re an underexplored genre.

Bit Rat Singularity is meant to be a kind of teaser game. It’s a smaller game than you’d expect, with probably fewer levels than you might like if you’re a hardcore puzzler. I’m not, I’m not great at this kind of puzzle, but I still had fun playing it, exploring it, and listening to the story the game presented.

It’s a path constructor, but rather than connecting pipes so water can flow through it, you’re connecting nodes on a network. Great, a simple expansion, and an existing one we’ve seen in other games like Uplink. In this case, the network is simplified, all the rules are abstracted, and once you get the basics handled, it starts to introduce things like limitations on how many nodes you can maintain, how you can connect them to one another, managing different resources as you try to construct your path out of the level.

It’s a great execution and part of what I love about it is that the game is often about constructing destructive pathways. Sometimes, to get your path to the end to work, you have to wreck what you’ve made – sometimes risking marooning yourself while you work, using one or two temporary measures that you need to dismantle, step by step, in the right order, which makes the whole thing more interesting than just a linear ‘from A to B.’

There’s a narrative that ties into the idea of retrotech, that sort of ‘a past’s vision of a different future,’ where you’re dealing with big chunky server boxes that managed to create, and lose track of, a sentient AI. You’re that AI, and you’re making your way out of the space you’re in, with variable degrees of menace as you befriend the rats that live in the place. There are employees you may need to puppet a little bit, because, uh, they have chips in their head, and it’s all presented as a result of massive breakdown in the culture of the company.

I got this game as part of the Bundle for Racial Justice and equality. It’s only $2. It’s a really good little game, and odds are good, you bought that bundle and didn’t really check everything in it out. I’m trying to make a project of checking games in this bundle, because it’s full of gems, and it’s worth it to look at them, and think about how all these games, all these products, are made by people, and those people wanted to sign up to give away something to try and help this problem we’re dealing with.

You’re not alone in the struggle. There are so many people who don’t want the world to be like this.

We just gotta find one another and make friends.

Gruuwar!

Back in the day there was a paper product called a magazine, like the thing that I will always call a clip in a gun because it tweaks the nose of people I enjoy lightly teasing. You got a tree and you hammered it flat, and then you like, carved into it? I think? It’s hard to say. Anyway, Dragon Magazine was a thing and you could get a little bit of D&D content, every month, developed (hah) and playtested (pfft) by expert professionals (BAHA HAHA).

One month, they did a feature on ‘wild races’ – different race options that were a bit more monstery, a bit less common. This set of ‘different ideas’ was a set that kind of feels standard now – there was an elemental rocky person, there was a spooky, gloomy one, and there was a cat person. This is kind of the three basic spaces that it seems that edition of the game had going on, the negative space that designers were overwhelmingly drawn to. Rock, cat, goth.

Also, mixed in amongst them, there was the throw-it-in, why-not creature of the Gruwaar.

Who I misread, and spent the intervening fifteen years referring to as the Gruuwar.

The Gruuwar as presented were almost immediately gone from my head. What I got to start with was that they were a race of rangy, secretive, skinny blue people covered in fur. Going back and consulting the magazine recently, I found that they sounded kind of like obnoxious jerks, and that my own take on the culture was so blatantly contrary as to be preposterous.

My Gruuwar are a race of slight, trouble-averse fey-based people, prone to mischief and theft, tied to henges and ancient stones, as gates and anchors for their teleporting powers. They had a war with the Shadar-Kai (which they lost), and their own little corners of the Feywild, made of over-large versions of common small plants. In my mind, they feel a bit more Welsh or Irish than the more British and French fairy folk of the Monster Manual, but a people that live in those spaces and still need to do things like get food and water and occasionally steal sausages and beer.

This got me thinking about wide races and pocket races. Wide races are those that you use all over a setting. My examples of half-elves, elves, and orcs all fit in that space already – creatures that exist in large enough quantities and over a diverse enough space that they have cultures that are separate from their own cultural stock. I think a setting wants a decent mix of these – after all you want room enough that humans can look reasonably like a variety of human cultures that already exist. Not to ripoff 1:1, but if I want to make an armoured knight who draws on say, French history as their general story source, that’s easy. Harder if I want to make something that’s like Saladin’s guard, or Admiral Yi’s crew. I don’t want to say ‘these cultural overtones belong exclusively to this race’ either – so if someone likes Korean style armour styles, and they want to play an Orc, that means that in the wide spaces where Korean-style stuff exists, there needs to be room for Orcs that can wear that gear without that gear being explicitly orcish.

Pocket races, on the other hand, are great for when you want a culture to be reasonably unified, often around a physical trait that’s hard to explore otherwise. Raptorans, for example, or Winged Elves like the Avariel – if they were widespread, they’d have a big impact in the world. To keep the world looking reasonably the way you want it to and not shaped by these elements, you need to keep this population small, and isolated (hence ‘pocket’).

The Gruuwar – my Gruuwar – are one of my favourite pocket races. They live up in the highlands, they hide behind cairns, and they mostly want to be left alone. One or two of them run around in the Realm of Iron, driven by a want for adventure, and they can be a player option – and even an avenue to introduce strange and mysterious stories, a bridge to the Fair Realm. Also, they can be cute and fun. It’s a culture of potential nightcrawlers, confused by player’s ways, but happy to learn and even more happy to swipe.

But they don’t need to be everywhere, and making them everywhere would disrupt the world to accommodate them.

Learn when to wield these two different ways to handle a culture.

Fat Guys With A Chain

Hey, here’s a thing that character designers do a lot.

In videogames, there is an archetype you’ll see when you look for a fat man. In fact, in fighting and action games it’s almost the only option for a fat man. It’s pretty much exactly what it says on the tin: The character is a fat man with a chain. There’s room for a lot of other details – like how fatness is also often coupled with gastric and oral details (fire breath and fart powers), or ‘non-masculine’ behaviour (so crybaby emotionality or flamboyance), but the character is still, foundationally, a fat man with a chain. Three simple words:

Fat. The character is physically large and round, and that roundness is presented as part of the character’s body, not an outfit they sit in or wear around.

Man. The character is coded masculine and adult, unambiguously so.

Chain. The character carries around a weapon that is a large metal chain.

Before I go on, I am not an expert in fat characters or how to design them, I am not an expert in what fat characters should or should not be. I don’t think I’m part of that conversation nor should I be – not because I am not fat or related to fatness, but because I haven’t done the homework. I’m thinking about this game design and how form and function interact. The example characters I’m using here are Chang from King of Fighters, Birdie from Street Fighter, Road Hog from Overwatch and Pudge from Dota 2.

The games these Fat Dudes With Chains are all from may seem very different – but they are all games with a fundamental importance to the idea of controlling space. MOBAs, fight games and arena FPSes, they’re all about controlling your opponent’s access to a space. Most characters control this space in a variety of ways: ranged weapons are common, but so are traps, mezzes, pursuit powers (think like Jhanna in Heroes of the Storm), barriers, all that good stuff, but also crucially, just the ability to move in those spaces. Position yourself and you effect your opponent’s options.

Historically, I suspect animating a chain nicely is relatively easy these days. If you check out how Chang from King of Fighters worked, he used the BALL more, which, again, a bit easier to animate. Still, he has the chain, and he can use it to extend the ball at distance, and give himself some reach, to get around that problem of moving fast.

The fat dude with a chain idea is hypothetically interesting: he can use his fatness as a counterweight, and force you, the other, to deal with his fatness, turning his fatness into a tool that he can use. This is not an inherently bad idea! The chain can move fast, and gives him reach without necessarily meaning that he moves his body very fast through that space. The chain gets to be an extension of his physical power that isn’t ‘letting the fat guy move fast.’

Here’s the thing though, there’s a base assumption here about why the fat guy needs the chain: He can’t be fast. That’s basically it. The fat man with a chain isn’t allowed to move fast, and the question then becomes: Why can’t he, though?

The first answer tends to involve the word ‘realistic’ or ‘realism,’ and that’s stupid. Realism isn’t important, feeling real is – and these games feature gigantic dudes like Juzoh, who is just as big but very capable of moving fast and dodging out of the way of dangerous attacks at a moment’s notice. Also, these games have fireballs in them.

Then the question tends to settle around ‘metaphor’ or ‘meaning’ about the characters, and then you’re left squirming as to why you’re defining your world by what, in a space of impossible humans, a fat person can’t do.

I’m very sympathetic to the idea of the big fat dude with a chain as a character being a cool design. Honestly, I think those elements could be used in a rad way. I like chain fighters, and I haven’t seen many big fat guys in these games that feels like someone I could like. But look at how Fat Dudes with a Chain outnumber All Other Fat Characters Period, and then ask yourself why the fuck, with all the mechanics available to every other body type, the fat guys keep getting this.

Now, I think ‘fat guy with a chain in an area control game’ works, because like I said, it gives a slow character reach, it lets him turn his body into a problem for others who aren’t familiar/aware of how to deal with that, but why not literally any of the other choices?

It’s not like big fat men can’t do things quickly. I’ve met big fat guys who can move their hands fast and can get themselves moving just as quick, and that’s reality, a place where gravity matters and nobody can jump twelve feet in the air at a dead stop. Why can’t a big fat dude be a dancer? And not a point of comedy dancer, but like actually just fast? Why can’t he be a teleporting ninja? Why can’t he be a mez-thrower trap-maker? Wrecking Ball from Overwatch could have been a big, fast moving fat guy. Also a joke, but it’s still a second fat guy and it isn’t a dude with a chain.

What you’re going to find is that there’s this desire to make the chain guy and the fat guy is the only natural home for that and they’re not going to make a second fat guy.

Overwatch has 29 characters. SNK’s character roster is preposterous and Chang is still the most obvious fat guy they have (and he has a chain). Street Fighter has Birdie and… god, anyone else? Heroes of the Storm has 85 characters. League of Legends has 143 characters. Again, in these spaces, there are a tiny number of fat characters, and those fat characters are more likely to have a chain than not.

The fat dude with a chain is a thing you can do. It’s just it’s really lazy, extremely basic, and tends to feed into an existing trope space where people aren’t doing enough to experiment and stretch their limits. You can do it, but may I suggest, instead, trying the tiniest bit harder.

(If you wholeheartedly love your Big Chainy Round Boys, let that love show)

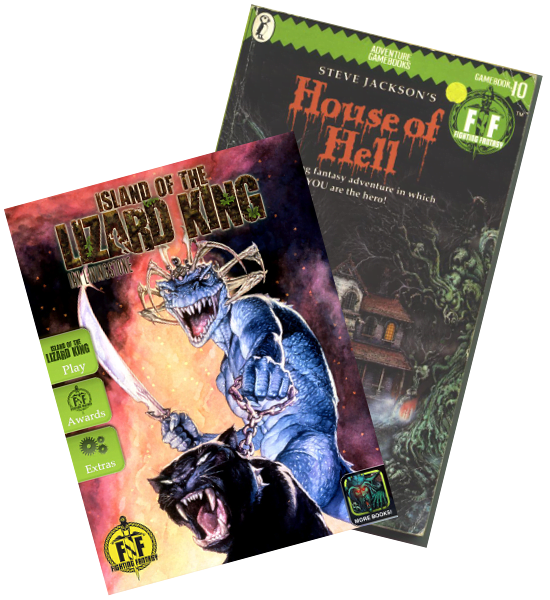

Expanding Fighting Fantasy

Thinking about solo adventures.

Far be it from me to point at the everything right now, but you may not realise it, but a lot of normal avenues for me are cut off – I don’t have access to playtest groups right now. Despite this, people are still TTRPG’in it up, tabletop living in online forms like Magic: The Gathering’s camera systems or Tabletop Simulator and the like. Also, Discord is getting a workout as a RPG room for a lot of people, and I know that my booklet games have been selling well on DriveThru.

That got me thinking: What can I do with just a book, for people who don’t have a ton of room or time to play with other people right now?

I loved the Fighting Fantasy books as a kid, because I also didn’t have access to specialised equipment and I didn’t have any friends. These books were an adventure that I could play and share with only the single monopoly dice out of my second hand boardgame we kept in the cupboard. They also could be obtained from the libary and local book exchange and crucially, not paid for with money.

If the main thing of mine people are buying right now is a book, and I want to give people stories and adventures and settings to play around in, then what about a solo RPG gamebook? That seems an interesting idea to at least explore.

There’s going to be a linked question here, which is, “Well, why not do this in twine?” or “Why not make this as an actual video game?” or “Why does this have to use a deck of cards when this other thing could do the job?” and the answer to that, largely, is shut up.

Not to be entirely rude, but the reason to do things with this medium is to do things with this medium. I’m not trying to get into programming languages – I know how to design game, I know how to design a game narrative, and I know how to format a book. What’s more, when you start using a digital model, you introduce more tools that often will handle things you do better – things like tracking inventory and whatnot. If you’re dealing with a gamebook or a pdf reader, you can tell the reader they have to do something, if you’re non-confusing, the player will be able to make it work.

A few ideas for this!

1. Flow

The typical problem of a gamebook is that you can emulate a linear flow from point A to point B, but it’s often hard to make a book construct a space. This is because some elements are time-sensitive – the first time you enter a room, you may encounter a version of the room that’s got things in it, but once you deal with them, the book has no inherent way to track that.

Now, there is an option for this – to treat the narrative as an entirely linear flow. Lots of good tricks here; using it as a narrative story that works as part of a journey is pretty good when you deal with something like the Lone Wolf books by Joe Dever. You could also make the narrative about being pursued – backtracking is inherently a problem.

There’s also the hamfisted way some of these narratives work by teleporting you places, or having you kidnapped or moved on. That’s a thing to bear in mind.

One idea for playing with memory is that your character sheet has a fold-over section, with a lot of out-of-context marks on it; when you do the thing the context mark indicates, you make a mark on the non-folded section, and that means that when you eventually flip that section out, you have a bunch of points that represent things you did, and they then send you to a story point that relates to that.

2. Adding Cards

A way to make the game remember – or forget – things is to use some cards. A deck of playing cards could be used to break up into a number of decks; you could have a final encounter represented by a few cards on a table, as a form of rudimentary AI. You could have treasure decks that mean you don’t find the same items in the same locations all the time.

You can also use cards to represent accomplishments – when successful, you can remove cards from a deck, so that later in the dungeon, they won’t show up. This can also be used to make the combat system more complicated in an interesting way.

I’m particularly interested in this because of how it relates to using a deck of cards to randomise encounters and add resistance without necessarily making the bulk of the book into repeating workhorse enemies and monsters.

3. Legacy Elements

Asking someone to physically write on the book is a bit sketchy, but you could have a legacy character sheet with a fold-out section that lets you draw on specific sections of the sheet to indicate things that have changed. Then you can use that section of the sheet to relate to the next (or all next sheets that follow, depending on how you feel about roguelikes).

This is particularly interesting because if entries are numbered, it’s entirely possible that you can make some entries go away with legacy rules; you have an entry that’s only accessible through the legacy elements, threads of story you can’t reach in the first play, but can in the second. That there’s hypertext.