Stop Being An Asshole About Fidget Spinners

Last year was the year of the Fidget Spinner, which is to say, it was the year people noticed the existence of dedicated stim toys and started to make a thing about it. During this time, teachers began the eternal gripe about whether or not they’re entitled to the attention of students, something that philosophically, I’m sort of resistant to. It’s not so much a resistance to the idea as much as it is surrender to its impossibility. If you’re a teacher, and you’re dealing with students who aren’t paying attention to you, that’s on you. Your job is to communicate ideas to the student in a way that they can remember. If they’re not engaging – if they’re not even trying – and you can’t find a way to make them that works for you too, then the two of you aren’t compatible.

The thing that blows me out about it was that the whole regime was just assholery all the way down. It wasn’t some sort of brilliant incisive conversation, not even slightly. You’d see people ostensibly employed in the task of scientific research or pedagogy or parenting or anything, people who you’d think have some degree of appreciation for nuance and maybe a recognition of how kids behave, acting like fidget spinners were the ding-danging apocalypse.

I mean, consider that adults do a ton of annoying stuff that other people put up with but they never realise how much people are ignoring it, because it’s not normal to call out strangers for being weird. If I stand at the bus stop clicking a pen nobody at the bus stop is going to tell me off for it, not because it doesn’t bug them, but because you respect other people’s boundaries.

The main thing I took out of the whole lesson was that the people you saw complaining the most about trying to distract people from fidget spinners were that they were people obviously uncomfortable with being shown that they’re not good at holding an audience’s attention. If people are going to zone out during your class, the fidget spinner’s not going to help them do it faster.

Literally every reason to ban fidget spinners is a reason to ban pens and paper.

The Hyperlink Is The Message

What do you think it means of a culture where every idea we have can be expressed on a page, with a direct link from everything we have to say to another thing that explains that thing? Do you think it’d make us more appreciative of context? Do you think we’d like things more if we could always be comfortable knowing a cite was backing us up? Or do you think that we’d start to replicate that same expression with other people – with the idea that every piece of text was obligated to provide its own citations and depth? Do you think it’s a coincidence that the current generation of toxic masculinity takes the form of nerds being confident that they are The Rightest each time?

Sodom Me, So Do You

The story of the city of Sodom is barely worth recapping, but in case you’ve never heard it, basically there was this place that God didn’t like that was basically named Doomedsville, and the only good people who lived there were shown in one incident how they were too good to live there, before God told them the town was hecked and they left. I’m glossing over some plot points, but it’s honestly not important, because what’s really remarkable about this story is what it’s about.

See, right now, if you ask people, it’s about the sexual immorality of the city, the way that the people of Sodom used to stick their hoo-hahs into butt-holes and that’s why it was a sign of what a problem things could be. That’s why God hates gay marriage.

Except those people, these days, are also opposed by people, equally certain of their familiarity with the religious texts of the now, who want to assert to you that, in fact, the sin of Sodom was their failure to show the messengers proper comfort: That the story of Sodom was a place that failed to respect people enough, and right, and therefore, God loves gay marriage.

This is not, in any way new.

Back during the 1930s, the city of Sodom was a story about a failure of the people to care for their travellers and interlopers, brought up as an example of people who weren’t in the proper spirit of Christian Charity. In the 1940s and 1920s, Sodom and Gomorrah were known to be about the vile practice of race-mixing. In the 1890s, Kelogg was certain that Sodom and Gomorrah were a story about the foulness of indulgent humanity who ate fancy food.

Now this is no secret to anyone familiar with Christian movements: Everything in the story is just a justification for today’s latest problem, and nobody wants to read any further than the destruction of the city for their metaphor.

Tails Has Two Buttholes (Philosophically)

Hi there, everyone, here’s a blog post about how Tails the Fox from the Sonic The Hedgehog games must have two buttholes.

The Fear of the White Slave

The stories we tell, and how we tell them, shape our worldview. This isn’t ‘media programs you,’ not a satanic panic fear-of-the-demons-in-your-media, but something slower, more grinding, more insidious. There’s an acretion of the world around you as you pass over it, little bits of the everyday. Making everyone’s clothes show ads, we thought, would be about making sure you were always showing off the hash-tag brand. Turns out that it mostly just meant people saw ads on clothes as normal and not worth noticing any more.

It’s hard to turn that kind of ubiquity into money in a pragmatic one-on-one sense. It’s difficult to monetise a brand if the main job monetising it is to be everywhere all at once, you need a certain scale for that to have an impact. You need to be Pepsi, for example. What you can do with it, though, is reinforce an idea of what’s normal, and thousands of sources doing it all the time can do a lot to shape that idea of normal.

It’s Marketing Whiteness.

CW, gunna talk about slavery and fundamentalism and whiteness and dismiss the historicity of the Bible, which just gets some people up in a dander.

Continue Reading →The Power Of Hate

I like pigs.

It’s a weird thing, considering. Maybe it’s a childhood story of Babe. Maybe it’s after being raised in a weirdo Christian cult, I thought the ‘unclean’ label they got was a bit rough. Maybe it’s Asterix comics that made it look like the poor boars were on the losing side of things.

But I like pigs.

CW ahead for descriptions of war and some unpleasant ways we refer to history.

Continue Reading →Doctor Scaramanga’s Wild Ride

Five years ago, I spoke about myself very differently.

The Traits Of Objects

You may have heard about the idea of ‘objectification.’ When I wrote about Daredevil, I trotted out a list – Instrumentality, Agency, Ownership, Fungibility, Violability, and Subjectivity. Where’d that list come from? Is it a tool you can use for your own writing?

One of the things I like with critical tools is that you can turn them on work that exists, and illuminate traits of the work you wouldn’t otherwise notice, but also, like an inverted puzzle piece, you can turn the tool on a work you’re developing yourself, and in the process, see spaces you can use to fill things out to achieve what you want. In this case, the tool is useful for avoiding the objectification of a character, which is to say, you can use this checklist to imbue a character with character.

As for the list’s origin, it’s from the work of Martha Nussbaum, and her writing was about people, not about media. It was also expanded by Rae Langton – whose work primarily focuses on sex and pornography. I don’t have a strong grounding in either of these creators, and I have the nagging feeling that digging into the views of a pair of 50+ year old Feminist Philosophers will find something nasty and TERFy. So don’t take my appreciation of this tool as an endorsement of them.

The full list, including both Nussbaum and Langton’s categories, and the questions they ask, is as follows:

- Instrumentality: Does this character exist to only enact the purpose of another? Are they a tool? Could you replace them with a vending machine?

- Agency: Is the character ever demonstrated as having their own purpose, their own ability to make decisions for themselves?

- Ownership: Is the character ever depicted as being literally the property of another? And if they are, is that depiction ever showing that as being reasonable? Parents, for example, are often depicted as owning their children. How do you think of that relationship?

- Fungibility: Can the character be swapped for another character of a similar type? Is the character replaceable? How would the actions of the character differ if another character was called upon to do the same thing?

- Violability: Can people act on the character without consequence? Can you punch them with no followup?

- Subjectivity: Does the character’s individual experience and personal opinion ever matter? When they disagree with someone is it because of a personal interpretation of events? What fuels that thought?

- Reduction To Body: Can the character be thought of as just a particular component of their body? Are they a fist to attack someone with, a foot to step on someone? This is very common in pornography – is a character, for lack of a less crude term ‘Tits The Girl?’

- Reduction To Appearance: Does a character matter primarily in terms of how appealing they are to the senses? A good test of this again, is to check how these characters could be organised in terms of being ‘the hottest’ or ranked for appearance.

- Silencing: Is the character voiceless? Are they treated as if they are voiceless? Does it ever matter if they say anything? Do other people react to what they have to say?

Sometimes there are some really weird things you can get by applying this toolset. For example, lots of the characters in Joss Whedon’s work are fungible – they almost all can say the same lines of dialogue. Zack Snyder’s Perry White in Batman V Superman hasn’t really got Subjectivity – he exists to oppose Lois Lane’s efforts, without a justifiable rationale for doing so. But you wouldn’t necessarily assume that Perry White is objectified as much, in this case, as he is just an object.

Not every character in a story needs to be a non-object. There will always be room for goons and audiences and randoms. Stories thrive on having objects in them. The thing to look out for in your own work is if all the objects you’re using have common traits – if all the black people in your story, for example, are fungible, you probably have a problem. If when you need a random character to dismiss as being meaningless, you reach to make it a woman, you’ve got to wonder why you keep doing that.

And also knock that off.

This list also makes a valuable way to examine your characters and see if there are new ways you can add dimensions to them. Make them more real. Just recognise that sometimes, a messenger can just be a messenger, they don’t need a backstory and a family and seven layers of motivation if they’re going to turn up and tell you that Rosencrantz and Gildenstern are dead.

Reversing Footnotes

At some point in my childhood, I remember mentioning something I’d read in a book – which I had, but since I was four, I didn’t realise this was gauche. It was immediately rebuked as ‘not interesting,’ because ‘I just read it in a book.’

Then I spent my entire life trying to hide the fact I read books.

Telling people about stuff you’ve read, ideas you’ve heard, concepts you accumulated, life underscored, was rude, and weird, and gross and boring. You had to act as if you came up with things yourself, unless you were quoting television programs. I made it a habit to synthesise things in my head – it was not so simple as to read something and learn it, I had to find some way to restate it so it sounded like me saying it.

When I hit university, this behaviour, this habit, was proven to be not actually the way you should do things. University was a process of learning that being able to point to your influences, being able to direct where your process came from, to give meaningful context of what you had interpreted and found, was pretty much everything. I did alright in university, but this was overwhelmingly the hardest and most daunting component of my work. And then I started on my Honours thesis, a process that involved literally the opposite.

My thesis, at its core, was showing how I could play a game, interpret that game, then use components of what I experienced in that game to make a new game, documenting the point of inspiration and conception of different mechanisms. And moving on, this seems to be what I’d work on next: showing the process so people can see how it goes and see if they can do the same thing.

The Pisscourse

Sure, let’s do this. Why not. Why not. It’s just a Daily Mail article.

In mid September 2017 the Daily Mail copy-pasted an article – more or less – which was about little boys peeing on things, and science, and gender essentialism and making women researchers look silly, and they love that kind of thing. You can almost test whether or not a story will show up on the Daily Mail if you imagine whether or not the average Daily Mail reader could read it and either dismiss the ‘expert’ they laughingly frame as an idiot, or act as if ‘well of course, who doesn’t know that.’ This one got to add a bit of gender essentialism and Terfy Overtonse, so of course this was going to be a hit.

The article is being shared around as if the Daily Mail had shared quack science proving that men are better at physics because they pee on things, and then dismissed this science with the evidence that urinals are dirty. You probably saw this joke. A few times.

There are three problems with this article – which I’m not linking. Before we go on, this article is going to talk about dick-havers and refer to them as generally male. This is not the absolute case. This is not what all dick-havers are. Just wanted to get that out there. When we talk about structural power and things Men do, however, it is very common that most men have penises, and that’s part of the assumptions of this article. So if I sound like I’m being Not Actively Trans-Inclusive enough please recognise it is a shorthand when talking about existing Men-based power structures, which are notoriously unfriendly to trans women and also tend towards disqualify and exclude them from wielding privilege.

Anyway, with that in mind: Here’s a fold!

Making Fun, Episode 3 – Defending Candyland

Remakes: Reboots, Remasters and Recreations

In the age of the easy remix, the re-use, the recycling of media concepts and design spaces and cultural concepts. It’s a space where we have a lot of different terms being used for different kinds of media. For my own purposes, I feel I need to define the meaningful differences between Remakes, Reboots, Remasters and, with new and fresh examples, Recreations.

The Remake is a global term, here. It’s just used so vaguely that it’s hard to really pin down what a ‘remake’ is. Was Full Metal Alchemist: Brotherhood a remake of Full Metal Alchemist? Sort of. Basically, in this case, I’m going to use remake as a way to refer to any new work that’s a new form of an existing work that’s designed to not require previous experience with the work. Each of these other terms refers to a specific type of remake.

A Reboot serves as a way to restart the work, a new point for someone who had no experience to start experiencing the work. A reboot wants to build something out of similar space, wants to use the iconography, it definitely wants to evoke the original, but a reboot is notable for showing you what the rebooter thinks matters to the original.

Here’s an example of four different reboots in one series: Each one was meant to accommodate major changes in the environment the franchise wanted to exist in.

Reboots are really at their best when there’s not a lot of there there, or when you’re making a work move from one form to another. While you might not consider an adaptation a reboot, they both use the same tools. It’s about taking away as much of what doesn’t work in your new form.

A Remaster is more like a translation: Conceptually, you are trying to make the thing again, that functionally works the same way, but with the new tools for presentation. It’s better audio quality, it’s more sound channels, it’s higher resolution images. In the case of some material forms, like film, a remaster can be just taking the production-quality materials and using them to create a new consumer-level version.

The recent trend towards remastering Lucasarts properties – or perhaps just a few classic examples like the Monkey Island games has had different variations on this. In the case of Full Throttle, pictured, the overall spirit is very much preserved, probably because they could work from a lot of similar sources.

One possibly controversial example of this usage of a Remaster is Gus Van Sant’s Psycho, a shot-for-shot recreation of the original Alfred Hitchcock movie from 1960. While this Remaster didn’t involve any of the original footage in creation, it nonetheless sought to be a version of the original in as high a quality as possible, with almost no deviation from the original.

And finally, the most challenging to do well: The Recreation. A recreation, for the sake of this conversation is something above and beyond what a Remaster or a Reboot can do. Recreations are reboots, but, they aren’t just about starting the continuity of the series over; recreations can be about the new continuity and about replicating the story beats or narrative components of the original.

The thing I need this term for, however, is Voltron: Legendary Defender.

Voltron: Legendary Defender isn’t just an attempt to tell the story of the original Voltron series, any of them. It’s not an attempt to update the same plot beats and introduce us to that story. Galaxy Defenders is a recreation of a feeling of the way the original series worked out. It’s a series that takes the same basic idea and ideology of the original story and tries to tell a new story with the same pieces.

The issue I have is that if you simply call it a remake that can miss the basic premise of what the series does. Voltron: Legendary Defender is a series that wants to be the Voltron series you remember and know isn’t there if you ever went back to look for it. It’s tight, dense, and it uses a the set of storytelling tools, animation tools, and trope frameworks we’ve developed in the twenty-five years since Voltron was new. There is, simply put, a lot of stuff in Voltron: Legendary Defender that wasn’t at all in the original Voltron.

Maybe this is all a bit unnecessary. Maybe I just want to tell you how cool Voltron is. Maybe I should just dedicate some time to that. Well, listen, you.

Booth’s Unstructure

Here’s a term that game developers should know about from academic spaces:

Unstructure

Unstructure is an idea from Paul Booth’s Game Play: Paratextuality in Contemporary Board Games. In this book Booth needs some way to describe the concept space that games create that is both concordant with human-manageable rules, and yet not immediately procedurally compatible with human interpreters.

Big mouthful there, so let’s try rephrasing it. Unstructure is the way a game uses systems that a person can manage to create scenarios that people can’t immediately predict. Some games don’t really have unstructure – Blackjack, for example, or Bridge, or Backgammon, for example. Games that do, however, are those games that are usually trying to represent a world with many people acting in it, some of whom aren’t really ‘in’ the game at all – the movement of traders, or the behaviour of monsters, or the whims of traders and people. Even a game like Monopoly has unstructure, where it uses chance and community chest cards to represent the goings-on in the players’ lives that have nothing to do with their surveying and buying property.

Unstructure is a thing for games that are trying to create a metaphor or a hypothetical space. The example of Unstructure that Booth uses in the book is Arkham Horror, a game that spreads systems broadly across a board, across different subsystems – people you deal with, events that happen, monsters that act – and in so doing creates a scenario that is both generated by things you can look at, read, and explain to toher players, and understand, that is still complicated enough that you can’t necessarily solve it.

A game Booth doesn’t cite in the book but which serves this really well is Betrayal at the House on the Hill, where the systems of the game are extremely well suited to hide from you just what haunt will happen, how it will happen, and who is going to be the traitor. This works really well in that game because it keeps you from being able to predict who will be the traitor, putting a spicy edge on the cooperative exploration part of the game.

The reason I think you want to know about – and have access to – unstructure is a concept is because it lets you know what you need, how much of it you need, and ways to build with it or build away from it. What Unstructure gives you is a way to describe just how much stuff you need going on in your game that players have no control over, and whether or not those players can manage to keep straight what’s going on. Some games may make it too easy to deduce the behaviour of the game, meaning the unstructure collapses and becomes something predictable or procedural. Some games may make it too hard to perceive random events as being about this world space, and make the game feel fundamentally random (hi, Monopoly).

The reason I think you want to know about – and have access to – unstructure is a concept is because it lets you know what you need, how much of it you need, and ways to build with it or build away from it. What Unstructure gives you is a way to describe just how much stuff you need going on in your game that players have no control over, and whether or not those players can manage to keep straight what’s going on. Some games may make it too easy to deduce the behaviour of the game, meaning the unstructure collapses and becomes something predictable or procedural. Some games may make it too hard to perceive random events as being about this world space, and make the game feel fundamentally random (hi, Monopoly).

Unstructure’s just another tool to describe ways you want the game to work, and it’s worth having.

Do Daddies Dream Problematic Dreams?

I’ve written about Problematic in the past, with the simple premise that there are no non-problematic faves, and the baked-in nature of the colonialist world we live in is fundamentally damaged. Recent events (a hot take shot from the hip) put the term in stark relief and so, since you’re all so very interested in telling me what I should think about it, clearly you’ll be interested to hear me expound. Right? Right? You’re not just looking to complain at a stranger?

This is spurred in part by recent reading about Dream Daddy. Because that’s a thing I started caring about despite having literally no interest, whatsoever, in wanting to play it, for any reason, at all, gosh dangit. With that in mind there’s going to be a minor spoiler to a thing I don’t care about but let’s take it under the fold anyway. It also involves the genders.

Continue Reading →

Notes: Procrastination, with Tim Pychyl

Here’s a thing I’m going to try and do more often. I watch educational programming or advertisements or reviews on Youtube from time to time and I take notes, and then I try to make sure I remember those notes. With that in mind, here’s a little talk about Procrastination I watched today and the notes I took on it.

Shout out to SJA for putting this video in my path.

- Emotional intelligence helps you with resisting procrastination

- Economic models are very cold and require rational actors

- Delays are not procrastination, but procrastination are delay

- There are actual developmental barriers here, and you can’t expect everyone to handle this the same way

- Negative reinforcement is about avoiding negative things, not about being punished

- ‘People who are procrastinating,’ not ‘procastinators’

- Working Under Pressure is a persistent myth

- Procrastination can be connected to more optimistic thought patterns, which I imagine makes it difficult with mental patterns like depression

- Goal intentions vs Implementation intentions not ‘I’ll work on the assignment tonight’ but ‘I will do the structural outline of section 2, after dinner.’

- Having definitive plans makes tasks seem more handleable.

Games And Language: What The H*ck Is Paratext

Paratext, the term, comes from the work of Gérard Genette, a literary theorist from France. He’s contemporary to Roland Barthes, the person who coined the now-widespread term ‘death of the author.’ Genette is the indie band of mainstream literary theory, the one you namedrop to indicate you didn’t just get your academic study from channers screaming about the death of the author in threads about the sanctity of subtitles or something. The book of his you’ll want to namedrop here is Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation.

To define Paratext, first we need to define text. Text is basically, the stuff of the work. If the work is a story book, for example, the text is literally just the story from beginning to end plus all the illustrations involved. If it’s a comic book, it’s every panel, how they’re arranged, what is in them, what they say. If it’s an instruction manual, it’s again, the words that make up that set of instructions, all the illustrations explaining it. The text of a painting is, basically, just the painting itself, the image and how it expresses itself in the world. Text is, broadly speaking, easiest to nail down when you’re talking about books: The text is the stuff the author (or authors) made to tell you.

“What about videogames,” you ask, well, that’s where things get muddier and where I think I disagree with some speakers on similar theories like Dan Olsen. But let’s save that for later.

When Genette coined the idea of paratext, he focused on books. Books, boy does Genette love books. Paratext, to him, was the threshold between the text and the not-text. Your lunch isn’t part of the text, very clearly, so that gap is easy to see – but the gap between the cover of the book and the text inside it, that’s not so obvious. The title of a book? Its table of contents? Publishers’ notes? The year it was published, as information? The weight of the book, the feel of it, the type of paper? These, Genette said, were its paratext, and they were the “a zone between text and off-text, a zone not only of transition but also of transaction: A privileged place of pragmatics and a strategy, of an influence on the public, an influence that… is at the service of a better reception for the text and a more pertinent reading of it.”

Which sounds fancy, but we’ve had some years to work on it. Paratext, once the idea was established, became pretty important to how we recognise the ways in which people experience media. Genette, for example, with his loving focus on books, didn’t do a lot of good for the unsighted people in the world who have a much more limited experience of the paratext of books, but definitely have a stronger attenuation to audiobooks. So we worked on ‘paratext.’ The working definition I use is:

Paratext is media created as a requirement to experience a text

So, if we’re talking about an audiobook, the voice actor and the speaker quality and the freedom of movement it gives you while you listen is itself, part of the paratext of that book. If we’re talking about a painting, a surrounding gallery environment is part of its paratext – you need those things to experience that painting though if the painting’s location or form changed, so to could that environment.

And now we’re on to videogames.

I forward the idea that play is paratext. That is, the text of a game is the stuff that’s ‘stuck down,’ in the game, without a ludonarrative element; it’s the artwork, the models, the spaces designed, the construction and cinematography of cutscenes, the choices in editing and when and where the audience is given and loses control. That is text, but in order to experience any of that, you have to play it. You, a hypothetical you, a player, has to engage with the work and create a play experience in order to ‘see’ that text.

But then, that asks, doesn’t that make the play experience ‘not-text’? Well, sort of but also not really. It’s a threshold. Just as how the original structure of a game may work on the basic assumption you’re not going to stand still and wait for the timer to run out, there are assumptions of things that make the text a reasonable experience. You bring yourself to the table and you play, and you interpret, and in so doing, you create part of the game that’s there for the play experience.

This is part of why it’s so hard to analyse videogames in particular in terms of broad textual analysis, because a lot of people have it in their heads that there’s one singular model of how the game ‘should’ play, or two or three forking forms of it, without embracing the idea that part of the game is the player experiencing it. That competence and skill change the way a game feels, that pre-baked literacy or an absence of it changes what a game says. The ludic ballet of a speedrunner glitching around whole problems while perfectly evading random generated elements is as much the game as is the stilting steps of the first-time gamer learning how to aim and walk at the same time. What’s more, the idea of this paratextual element means we can look at things in terms of the general ways in which players tend to be pushed – we can view the play paratext in aggregate of experiences (the way lots of people create the paratext) or we can view each paratext as an individual interpretation that has potential to be interesting for consideration.

If we recognise play as paratext, we recognise ourselves as part of the creation of it. And that, that right there, is one of the most powerful things about games: Games let us create some of the text for ourselves.

By the way, Genette is still alive and I really, really hope he’s not reading this because he’s an old bloke and I doubt he gives two toots about videogames.

The Assumed Relevance Of First

This video helped kicked me thinking about this for a bit so I’m going to just sit here while you watch it. Join me after the fold.

Making Friends And Having Trauma

Gunna talk about trauma! Jump away if you’d like!

The Values Of A Dollar: American Currency

I promised myself I wouldn’t just throw rocks at US currency for being bad, because let’s face it, most things in America can be pointed at as being a little bit crap. I could make articles for days, standing outside the United States saying look at what this asshole does or look at how this crappy crap works, isn’t it crap, and I don’t wanna be that guy. But.

Currency is a practical element of an economic nation, and that’s fine, I mean, if we’re going to have it, we’re going to need it, and I’m not going to get into Hill People conversations right now. But currency is more than a purely pragmatic piece of government infrastructure: It is the most commonly produced, reproduced, and seen artwork that a nation has. Currency lets you reflect, to your citizens, in everyday ways, things that matter to you all. It is one of those places where media and community can feed into one another, and thanks to their passive practical application people will slowly, osmotically internalise the importance of these figures.

Don’t get me wrong: Australians broadly speaking do not know the people on most of their currency. But when you use their names, they often can attach those names to people.

Now, I want to start complaining about American currency infrastructurally (why do you still have pennies and dollar bills and cotton notes you galloping goons), and there’s a time for that, but let’s not, and instead I’m going to talk about what’s on the notes. This is easy, compared to talking about the Australian notes, because the American notes are kind of churned out to a really basic theme.

Now, I’m just going to focus on the common circulation bills here: The $1, $2, $5, $10, $20, $50, and $100 notes. There are some bills of higher value than that, but they are silly, and dumb, and let’s throw rocks at them.

Anyway, in order, those bills feature on their front faces George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, Alexander Hamilton, Andrew Jackson, Ulysses S Grant, Ben Franklin. On the reverse, they feature The Seal of the United States, the Declaration of Independence, the Lincoln Memorial, the Treasury Department Building, The White House, The Capitol, and Independence Hall.

Now, this basic structure was picked in 1914, and has only been slightly changed since then (like, the bills shrunk). The people on bills can be basically broken into two major historical beats: The Civil War (Grant and Lincoln), and Founding Fathers-Era Stuff; early presidents and signitaries of the Declaration of Independence.

And… Andrew Jackson.

Andrew Jackson. What the fuck.

Content Warning: Following video contains some insensitive ways to describe what might have been mental illness or may have just been some gigantic asshole:

Andrew Jackson, in case you weren’t aware, is basically the kind of thing the Constitution was meant to prevent happening. You can scratch this pyramid of a life and see that every layer down reveals something worse. It wasn’t enough that his Presidential Inauguration party was so raucous he had to sneak out, fill bathtubs on the lawn with whiskey and then sneak in while his revellers ran out onto the lawn and get more hammered there. Andrew Jackson used to duel as a hobby – and no, I don’t mean he liked to fence, I mean he liked to go out behind the actual White House and shoot people in the face over ridiculous slights. At least once he was actually shot and responded by killing the person who shot him. This was while he was President. Jackson used his last days in office to recognise Texas as an independent country because he didn’t want that pro-slavery bastion of anti-Mexican sentiment to be ignored by an anti-slavery president coming after him. He committed actual acts of genocide, and I mean he was personally there, a lot, killing people. And then, as if to just add a little dash of irony, he didn’t want America to have banks or banknotes.

Why the fuck is this guy the special exception!?

I mean, set aside that the guy was a total raging asshole, then set aside that he was a complete fucking monster, and then set aside that he didn’t believe in money, you have to be able to value other stuff this guy did a lot more than things like not-murder, not-slavery and not-random-acts-of-pointless-violence. And that, right there, is kind of the problem with all these money people.

For the most part, these guys are notably, historically, for their part in creating America, or, more specifically, creating American government. Government that, again, see back up the top of the document, is at the very least, a little bit crap. And the reverse faces are all… monuments to, or instances of government. The lesson then, in the simplest possible way, is that the US Government wants Americans to think of the most artistically relevant part of their lives as, well, the US Government, but the US Government as expressed and represented by the historical context of old white slave owners signing documents and huffing about not paying taxes that they, themselves, were responsible for incurring.

But you know what else is interesting in this? The money, in its basic template, has been the same since 1914. The money is designed to evoke a timelessness, an aesthetic of ages and represent things that also do not change. So you have this common artwork that holds fast to history, if you can ignore all the ugly bits of history, and then emphasise them as important in their shaping of the aforementioned slightly crap system…

And then consider how Americans are resistant to systemic change.Consider how every American, every day, looks at art they are told is important, they associate with importance, and with living, that is of old dead men focused around one narrow window of time, doing one narrow band of things, and … okay, one total fucking maniac in the form of Jackson. You even have an example of change in the notes – Lincoln and Grant! They had a civil war, and that’s what it took to free slaves, because this country is that resistant to change, jesus christ.

What I’m saying is: Art of a culture reinforces and influences that culture’s attitudes, and America’s most common art is about how America, as it is, is totally fine, and stop complaining or trying to fix anything created by these divine flawless old guys.

And now

NOW

you’re thinking about adding Harriett Tubman to a note. On the obverse of an Andrew Jackson note, possibly? Because man, that’s not awkward – a man who murdered people for fucking fun as opposed to one of the great icons of humanitarian risk? A man who hated how people made a big deal about his pro-slavery views on the other side of a note to a woman who was a former slave?!

What the hell?!

It’s nice to put Harriett Tubman on a note. It’d be good too, to strip off the people who wrote about ‘all men created equal’ while they were treating women and black people like awfulness. But that’s the real gist of it: This is nice. There’s more to do. There’s a lot more. A lot better.

Also, there’s the possibility you don’t want anything to do with money and you find the idea of putting art of Hariett Tubman in every pocket across America as gross or vile because it’s part of capitalism. I’m not about to say that being against money is a bad thing, but I do feel like at least, right now, it is a part of art and culture.

Media Capitals

Reviewing my degree so far, one idea that’s come up and I thought was very interesting was the idea of media capitals, specifically the idea of places that create media as existing in middle spaces.Continue Reading →

*sniff* Are Videogames /Art/?

The question ‘are videogames art’ is a wonderful question because it lets you see who isn’t actually very well informed about what art is or maybe what videogames are. It’s the kind of question that derives from gallery culture – ‘it’s nice, but is it art‘ – that is explicitly meant to be a parody of things that don’t really happen much. It’s a joke about pretentious dipshits which is, itself, being taken seriously when it’s moved out of the fora of conventional artworks to the perspective of videogames.

It’s okay! Most of the people writing about this didn’t study art. Most of them are just … well, videogame players, and it seems that statistically, that’s not a perspective that brought to bear on a lot of conventionally-viewed-as-art. It’s why we keep talking about the Citizen Kane of videogames, because holy crap, you’ve heard of Citizen Kane? You must be a fancy sort of person type!

Look, art is not some arbitary threshold of meaning. Art is a composition, it is a component of things. Some art objects are made up of ‘mostly art.’ Some art objects are really only there to BE art, and those artworks are what a lot of us conventionally view as art. The idea that the sketchpad scribblings of a tumblr artist can be art but somehow the vast vistas of Dark Souls can’t be because one of them is designed to serve some form of a purpose, designed to be part of something else, is weird.

It’s a bit like saying because the Mona Lisa was a comissioned artwork it doesn’t really count as art, because it was made for a purpose.

It’s a charming little question, where one of my teachers summarised the conversation – on an academic level – thus:

“Are videogames art? Yes, now fuck off.”

It’s not a meaningful question, not a meaningful conversation, if you’ve actually had any acquaintance with the breadth of design and art. It’s a dismissable idea.

And now, videogame journalists – who I am sure are all lovely people, except those who are total toolbags – are going to circulate around thinkpieces and maybe some of them will bust out some first-level google scholar citations or maybe reference that thing they’re pretty sure they read that one time.

In the mean time, developers and creators will continue making art. Some of it won’t be particularly smart or good art. Some of it will be about expressing small, silly ideas. Some of it will just be aping other, earlier forms of art, things they’re familiar with, things they’ve wanted to do for a good long time but never really got around to doing.

We must unshackle our thinking from the notion that art means good art. That art is a term of quality and not a term referring to general traits.

Art is scattered throughout most of our creations. There are always parts of human designs that have, to some extent, an element that references our desire to express an idea or a creative position. You can think of art as glitter – it’s everywhere, it gets everywhere, and sometimes even if there’s only a little bit of it on a thing, you’ll still notice it, even unconsciously. Some objects are made of a lot of art, and some are made of almost none.

The space where we make choices in creation that lays between art and design is a curious one. After all, design is usually crafted with a tangible aim – “we want this object to do this.” – but art is somehow perceived as having intangible aims – “we want this object to make people feel this.”

I’ve written about videogame art before, of course. I’ve talked about how videogames are all art, and some of them are just crappy art. Some of them are just big art, too – the notion that videogame artwork is just an accidental structure of a scale we’re simply unused to. It’s interesting too, because it’s not like literally every single second of a movie has to be of such quality that it carries the entire piece – well, I mean, there’s some Kubrickian style scholars who may disagree.

But videogame art, at its core, is the art we have put in videogames, because we can’t help it.

All videogames are art, it’s just some of them aren’t very good art. Some of them don’t express very interesting ideas. Some of them are a bit silly. Some of them only want to express ideas like ‘I love this thing’ or ‘I don’t want to think about my life’ and that’s entirely okay.

Art is a sanctuary from the demands of an unscrupulous reality, not some arbitary threshold of acceptable ways to spend your time.

Genre Language

What follows below is some text I submitted to one of my classes which I’m kinda thinking about a lot. So hey, if you find it here, Automated Grading software system, let me know.

Japanese media that we mostly experience is very genre, which I refer to in class as being unscrutinised. Broadly speaking genre media isn’t being made for mass-market appeal, but more niche, which means that their creation is more a matter of, for lack of a better phrase, filling in the blanks. In the west, some of our great genre media industries is the realm of the Erotic Novel For Women – the Mills & Boon archetype, where the quality of any individual piece isn’t really regarded at all, as long as the work hits a certain number of targeted goals. Is the central woman bosomy and relateable? Is the hunky man she’s going to smooch adequately mysterious and brooding? Are there three or four sex scenes in an exotic location? Okay, we’re done.

This style of genre structure follows in a lot of anime and manga and videogame media, where it doesn’t matter so much about what characters do or say as long as they hit some well-established beats of story. This means that genre, in Japanese culture, has a wealthy sort of ‘concept language.’ Characters translate reasonably well into totally different forms because the archetypes themselves are structurally components of the character. A tsundere character is not seen as boring or cliché, because the point of the character is to fulfil some element of that archetype, or to defy it.

This is, to me, super interesting because it implies a sort of inherent media discourse. The idea of character archetypes has a language in this genre media – and it informs the way that media is then made.

‘Gamer’

I originally wrote this on August 24th last year. I didn’t post it, because I felt, at the time, that the last paragraph defeated the point of the whole article. Putting this grim crap behind a fold.Continue Reading →

Work Day – Nothin!

Today, over on the uni blog, I put together a piece of autoethnographic study on Godzilla and my own childhood as a weeb and the son of a boat person.

I’m tired and I’m cranky and I can’t think of anything funny to do with the letter ‘P’ so I guess that’s where the joke dies.

Class Day – Deck Building

I’m focusing on uni work today – as I will, most tuesdays, wednesdays, and thursdays – but today I had the chance to really rummage around in one class for deck-building games. That means today, I’ve been musing on deck-builder games, and with it, the idea of cardboard AI.

Right now, that text is over on my uni blog. Not going to link it, because I want to keep these two things separated as best I can – but it’s there. Maybe I’ll have more to say later tonight, but I want to make it clear: I’ve written some stuff today.

Refining Journalism

Journalism is, as I have said before, the task of putting information into context. That is, at its most basic, what it is. You’ll see people saying ‘this is news, that is journalism,’ and trying to define down what journalism is, hoping to hide journalism away in a box. Ironically, those people who do so often have to try and remove many other things from that task, of putting information in context – as if watching the news is not a task of taking your own day-to-day life and casting it against the context of other events that have transpired today.

Journalism is performed by almost everyone in the videogame industry, some poorly, some well. A lot of advertising copy lands on the desks of journalists after having been written by a journalist. It’s remarkably easy to convince people to print your words verbatim if you already speak in the language they want to use. Press releases are written, typically, by journalists. Charity fundraiser letters are written by journalists. News reports, even comedic ones, are written by journalists.

Lately, John Oliver and Jon Stewart have both been on my mind, because both have said they are comedians, not journalists, which shows how the word is used in their parlance. The idea that ‘journalists’ are some sort of special class of people; that using a half-hour show at night to tell jokes about a factual thing that happened, using the tone and tenor of a news program to make fun of it, but still to provide information in a meaningful context. In order to tell you jokes about a thing, they need to make sure you’re aware of and understand a thing. For their jokes, the news is part of the context. Rather than just shoot one-liners from the hip, though, they then put that information into context, as part of their presentation. It becomes part of the texture of what they do.

Class Blogging

Today was a day of reviewing my class blogs before they get submitted. Part of this has included looking over my talking/writing about Solastalgia, and the way we exist in a future where it’s very reasonable that a corporation can look at a few percentage points on a chart, decide to shut a product down, and as a direct result, cause a spread of depression and diminished activity. It’s possible for games, and the removal/death of those games to constitute a sort of medical emergency, psychological harm spread across a group of people.

Fucking weird.

Assignment Season

Got two research essays and a design doc to finish.

Expect fewer updates, or shorter updates.

Unless, I dunno, you piss me off and I need something bigger than a tweet to respond to it with.

Unconscious Literacy

Today I sat down and listened to a room full of people who thought they didn’t know much about science talking about how much they knew about science.

They knew about falsifiability.

They knew about burden of proof.

They knew about biases, and minimising them.

They knew about climate change.

They knew they could be fooled.

These people were sure they didn’t know much about science, but in one forty-minute conversation with two moderators, they showed that even if they didn’t know science, they had internalised scientific principles. They knew how to prove things. They knew how to understand things. They also knew that they didn’t know that much, and therefore, they should understate their level of scientific competence.

I went into this report – which is, yes, an analysis for class work – expecting to find a group of younger people than me, bein’ all youthful and not valuing what I valued. What I found was that they not only valued many of the same things I did, but they were humble about that. They did not think of themselves as scientifically literate, because literacy is background radiation at this point.

I think about this sort of thing a lot when I’m surrounded by computer programmers and scientists. I don’t mean this as a judgment on them, but they so often talk about users as cattle or savants; where they are sure of what users know and can utilise well without ever actually knowing, as if the experience of a user is something that can just be deduced like a cow’s movements, or the way a dog will behave when a ball is thrown.

Assessment Time

Today at uni it’s come down to ‘time to do final reports and such’ time of the semester. So far it’s been a really good, very easy semester which has worked out really well considering how weirdly horrible I’ve felt. Not just sick, but … really, really miserable and rotten. I can’t even attest to it being a side effect of uni work. I think it was just the sort of stuff I was trying to do with myself, all piling up at once and leaving me feeling exhausted and despairing.

I think a big part of this is just realism. I don’t have that much to say that’s worth hearing, I’m just another one of the many voices in the internet’s hindbrain trying to differentiate myself from the wall of noise. I’m just a blip. I signed up to uni thinking it would get me options in one of three fields and now I’m finding that all three of them are terrible ideas, and they won’t work, and they’re bad as well so nobody should be doing them, that kind of thing.

I just keep on circling that drain though.

Still, I have enjoyed the classwork this semester. I’m glad I have been trying to reduce the things in my life that make me miserable, which is why, a week from the last time I sat down to write about it, I’m really glad I stopped trying to force Mycroft. I still like the characters in that space – but I am just not the person, in this headspace, to try and write about them.

I wonder sometimes, what it’d be like, to be in that lucky time and space where churning out a book every month could be a full-time job. It seems like such a strange fantasy.

I did well, at least by my hopes and standards, at the two presentations and the first two blogging assessments. That’s super nice to know.

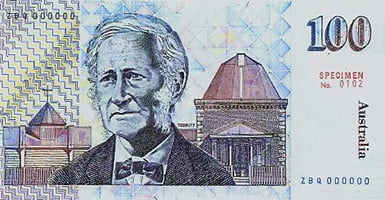

The Values Of A Dollar – $100

And now we come to the very last of the Australian bills. We’re almost done with this little tour of bills – having already done 5, 10, 20 and 50.

John Tebutt

%27%20fill-opacity%3D%27.5%27%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%235e5e5e%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22rotate(157%2052.9%20101.8)%20scale(116.11463%2070.52669)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23dedede%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(-72.49609%2035.81668%20-167.91804%20-339.88079%20351.6%2082.8)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23d8d8d8%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(-30.67631%20-34.8672%2065.9323%20-58.00753%2021.4%2032.1)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23d2d2d2%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(-15.66877%2027.23514%20-53.8029%20-30.9536%20197.4%2016.2)%22%2F%3E%3C%2Fg%3E%3C%2Fsvg%3E)

The old printing of the 100 featured on one side, John Tebutt, who can be simply desribed as ‘an astronomer.’ He discovered a comet, or specifically ‘the great comet of 1861,’ which was kinda neat, but there was no way to tell the people in the Royal Society in England about it because hey, the Pacific Ocean is quite a thing let me tell you. When the findings were checked and dated, Tebutt was correctly attributed as the first discoverer of that comet, and that’s where most folks’ stories would stop.

Instead, Tebutt went on to hand-build his own observatory near his dad’s home, and spend the next fifty years studying the stars from a position that had been largely untested. The rest of his career was tireless study and publication.

What’s really interesting to me is that in this printing he completes the arc of all of our currency featuring a scientist on it.

Douglas Mawson

%22%20transform%3D%22translate(.8%20.8)%20scale(1.5039)%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23e0e0e0%22%20cx%3D%2218%22%20cy%3D%2268%22%20rx%3D%2230%22%20ry%3D%22255%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%236a6a6a%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22rotate(-93.7%20127.9%20-17.7)%20scale(116.67285%2052.53926)%22%2F%3E%3Cpath%20fill%3D%22%236f6f6f%22%20d%3D%22M82.5%20152.1l3-87%2020%20.8-3%2087z%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23a7a7a7%22%20cx%3D%22233%22%20cy%3D%2245%22%20rx%3D%2237%22%20ry%3D%2284%22%2F%3E%3C%2Fg%3E%3C%2Fsvg%3E)

Douglas Mawson was also a scientist. But instead of building something in his dad’s backyard, he went down to Antarctica to study the rocks there. Mawson’s story of exploration of the Antarctic is sadly one of those stories that, like so many other exploration stories, has tragic and sad components; while Mawson lived to tell the tale, many dogs didn’t, and just bringing that fact to mind makes me sad.

On the other hand, it’s kinda weird that our currency featured a dude who once ate dogs.

It was pretty dire as experiences go, I don’t want to act like he’s a bad person. It’s just sad anyway.

Dame Nelly Melba

%22%20transform%3D%22translate(.6%20.6)%20scale(1.1914)%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23caddd7%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(53.3366%20-26.59265%20102.90272%20206.39092%20219.8%2049.5)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23576661%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(-13.5076%2055.55344%20-94.71297%20-23.02907%2060.8%2075.1)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%2332a981%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(-19.40671%20-1.01192%205.83877%20-111.97641%2012.8%2033.3)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%2341b48e%22%20cx%3D%22239%22%20cy%3D%2230%22%20rx%3D%2227%22%20ry%3D%2218%22%2F%3E%3C%2Fg%3E%3C%2Fsvg%3E)

In the second printing, however, rather than Antarctic explorers, we have Dame Nelly Melba, whose claim to fame in common parlance is the time someone else named a dessert after her, the Peach Melba – a dish ironically that features none of the name she’d been born with, but was for the name she chose. Nelly Melba, aka Helen Porter Mitchell, was one of the most famous operatic sopranos of the early 20th century.

What makes her significant in our history is that there was a point, in all seriousness, where we, a nation that claims to thrive on music and culture and art and poetry and science, were considered a place that could not yield actual artists, could not create actual ‘real’ culture. And from this came a woman whose voice thrilled the world.

Sir John Monash

%27%20fill-opacity%3D%27.5%27%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23c3c2b0%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22rotate(176.3%20144%205.1)%20scale(231.72204%2055.22651)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23307e68%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22rotate(149%20164.3%20122.8)%20scale(144.84461%2066.7313)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23979a2c%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22rotate(-102.5%2088.3%20-.7)%20scale(141.4759%2046.887)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%234fac94%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(-57.0254%20-10.98136%2022.46276%20-116.64747%20420%20112.5)%22%2F%3E%3C%2Fg%3E%3C%2Fsvg%3E)

Monash, whose name most commonly connects to a set of university campuses in Sydney, was an engineer who, when Australia was looking for a general, thought he could do a bit of that warring business. It’s kind of funny to me in hindsight that he, as an engineer, fills out the scientist requirement of this bill – because we often joke that engineers aren’t ‘scientists.’

John Monash was appointed to a leadership position for infantry in the First World War – a position that was met with resistance because this Australian was also a German and also a Jew.

If you know First World War history, the classic line is that the troops were lions commanded by donkeys. We created technology that outmoded our tactics; monstrous machine gun nests which we threw soldiers into, watching them being torn apart and somehow thinking that the progress we made was enough. It was a terrible, dreadful conflict, the kind of thing we don’t tend to even glamourise (except when someone in Britain wants to do a Christmas sale, rather tastelessly), and generally, we see the generals in charge of it as ignorant, at least.

Monash, however, was a technologist. He firmly believed that there needed to be a change in mindset of the military, a change that did not take root until years later, in the second world War, thanks to another German general: Rommel. Specifically, Monash had this to say about the role of the Infantry in the military.

the true role of infantry was not to expend itself upon heroic physical effort, not to wither away under merciless machine-gun fire, not to impale itself on hostile bayonets, nor to tear itself to pieces in hostile entanglements—(I am thinking of Pozières and Stormy Trench and Bullecourt, and other bloody fields)—but on the contrary, to advance under the maximum possible protection of the maximum possible array of mechanical resources,

Monash was hailed by other generals for this push, though they didn’t seem to listen to him very much. Eventually, when he was given full command of Australia’s military, he instated policies that called for an advance in technology to diminish the risk and harm to people.