October 2018 Wrapup!

October! The spookiest of months!

This month featured a strong theme through the Game Pile and Story Pile of spooky stuff. I mostly avoided horror videogames; I’m not really qualified to talk about the fundamental problems of games like Outlast and nobody is going to listen to me on things like Outlast 2. Instead, I looked at tabletop games and, then, because I’d tried to make a video about it, a tiny complaint about SOMA.

Note to self: Maybe do one on The Infernals sometime.

The articles I wrote this month that I was the most proud of were Your Worst Fan, which was about how even bad people who are stupid jerks will interpret media, Christopher Hitchens Was Just Good At Being A Dick, which is kinda self-explanatory, an article on Voice Acting I’ve had in the queue since July, and of course, my review of Neil Gaiman’s Trigger Warning, a middling book of pish.

The video this month was on Comstockery, an an effort to talk about some of the horror in media studies that has nothing to do with murders as we understand them. Lots of other media studies folk wanna talk about horror and the greater tools of storytelling as applied to it, after all. It seems to me that the horror experts are best served talking about horror in a big way – but I know me some messed up puritanical deviants.

October’s game is on the way, coming over the ocean in the form of a game that is still not quite properly named. There’s a print-and-play game up on my Patreon I made this month, which might get expanded (I hope) depending on playtesting and feedback.

The October shirts are these Eat Trash, Live Free shirts. You can get them on Redbubble (Raccoon and Ibis) and on Teepublic (Raccoon and Ibis).

October’s theme proved challenging. I had to coordinate what I was doing, which I recognised curtailed some of my common behaviours – pull open a window, dump text in it and throw it in the queue. It shaped my consumption habits for a month, and my horror game consumption just dropped off because all my attempts to play horror games got boring. I felt like I just didn’t have enough interesting things to say about horror, too. Horror’s a thing I feel you sort of need to build a corpus of expertise around to avoid saying anything pedestrian. You don’t need me to introduce the concept of The Final Girl, for example.

Also there are some horror games I played this year that I didn’t think to save my writing about until October. That would have been much smarter than what I did.

Anyway, onward!

Game Pile: Soma

This… will be short.

Comstock

Geanette, To Weebs

I’ve talked about Gerard Geanette, a French academic, who published books in the 1990s about a vision of media that we call structuralism. His idea was that you can divide media into different parts that all make up the experience, and the ways it change from person to person is a matter of changing parts of the structure while not necessarily changing parts of the text.

Also, Geanette? Looooved him some books.

Story Pile: Monster

I’ve talked about the challenge of talking about big work in the past. I sometimes use the term mile wide pie, where some experiences are so time consuming or have some single facet engaging enough that you can’t really judge the work as a whole. All I can do, really, is talk to you about my experience of the thing, but how can I do that without simply sitting by your side as I recount the whole thing? I don’t think there’s an interest in me doing a Manga Reread Podcast or something like that. Monster is a big series – eighteen volumes of manga, filled with short stories and diversions that reinforce the central theme of the story, things I could leave out of the retelling but which still matter to the story. Then there’s an anime, a rare example of an almost perfectly faithful adaptation that does as little as possible to change the original work, yet highlights just how tightly the manga is devised.

What I can offer instead then is a sort of snapshot. A handful of moments, things that stand out to me in a work that resonated with me powerfully. Before we go on, though, two warnings. One, I will talk about some of the events in this series.

Two, this series gets a lot of content warnings. It is not a light series, it is not a breezy read. Without comprehensive review, the book features child endangerment (and how), suicide, depression, repressed memories, child abuse, enfant terrible, actual literal real neo-Nazis, Hitler Stuff and good old fashioned violence, but really it’s quite sedate there. This is not gory, it is terrible. It is a horror story. It is an extremely horrifying horror story. It is also uplifting, and humanising, and helped me feel whole.

I want to talk to you about Monster.

Continue Reading →3.5 Memories – Singh Rager

Sometimes playing Dungeons and Dragons 3rd edition was like playing a game under a Mexican standoff. Part of it was our maturity as players and part of it was a very programmatic view of the game rules. There was a fairly widespread, commonly seen vision that there was a correct way to play the game, and you could use precedent and rules and various senior authorities to make your position the correct one. The thing is, these arguments weren’t fun and they’d eat all day and you’d get sick of them, so you wanted to avoid them.

What’s more, the game was so big that it wasn’t very easy for a DM to be sure about what their players could do, and it was often very awkward to roll with it when a player did something unexpected. If you were particularly strict about things, you’d sometimes watch as the game juddered to an almighty halt as you nerfed a player in-action, putting your foot down at the right moment to make a player feel bad. Especially bad when players had common goals, but you had to reign one in while leaving the other unrestrained. Rightness of it notwithstanding, it felt bad.

It wasn’t like the design didn’t encourage this kind of mindset, too – there were all sorts of monsters which were made explicitly to shut off particular abilities of player characters. Golems often were immune to magic in all but extremely specific ways, many monsters had totally unreasonable damage reduction or really weak saves in one category, and that was meant to represent a way that the players could prey on weak points, or, that you could punish players for their failings. DMs knew they had ‘the nasty stuff’ they could bust out, and it was stuff that almost never had any meaningful reason to be the way it was. You didn’t need to put Gricks anywhere, Gricks didn’t have powerful resonance. You didn’t need a Golem, representing a wizard’s hubris, you could just use all the other more interesting things wizards could do. Wizard players would never flipping bother with making a golem, too.

DMs stayed away from these things unless the players got uppity, and the players, in order to avoid arguments, tried to avoid getting uppity. One of the easiest ways to get uppity was to show off that you could exceed the challenges presented by the DM – which really, in hindsight, is such a silly thing. If a fight’s over fast, just implement that knowledge for next time.

Anway.

What this meant is that if you wanted to min-max, you kind of wanted to min max within boundaries of what the DM could handle. Combat was a good place to stay, because even the nuttiest combat build still tended to be limited by where it could physically stand and how many actions you got in a turn. Wizards could sidestep entire combats with utility spells, or scry-and-die boss monsters. Clerics could make armies and take over dragons, and druids were all that on rocket skates. The Artificer and Archivist waited nervously in the wings, hoping nobody would notice them, because they were somehow more busted than the other spellcasters.

If you wanted to min-max a melee combat type, though?

Well, boy, you could go buck. wild. there and it wouldn’t really matter too much. The most broken melee combatant in the game you could make was probably a wizard or cleric, after all, so if you got there without doing any of that nonsense, you were usually seen as ‘playing fair.’

So let’s talk about the Singh Rager, a 3.0 orphan that got nerfed by 3.5, and was good enough even after the nerf.

MTG: Halloween Commanders, Part Two

Once more, let’s look at some spooky, halloweeny-themed commanders, who might make a good centerpiece for a deck that lets you play to halloween themes. These are about trying to make decks that aren’t repetitive but still let you play with a nice, spooky horror space. And onwards!

Mad About Adam Jensen

I really don’t like Adam Jensen. The character from the Deus Ex franchise, and based on games’ count alone, the main thing the franchise is about. The guy who never asked for this. This guy.

Adam Jensen’s only limitations represented by his cybernetic augmentations are the moments when someone calls him out of a lineup to tell him that he, the cool looking super badass who doesn’t have conspicuous augs and has special privileges that keep him from being seriously detained, has been noticed. There’s inklings of his physiotherapy, of the recovery, shown in Deus Ex: Human Revolution, but it’s invisibled. It’s on his desk in his home and you never have to do it.

Adam Jensen isn’t in debt for his augs. He gets a super cool job that lets him do all the things he was doing beforehand, and the guy who could hypothetically charge him for the augs, repeatedly tells him that hey, no, it’s okay, it’s okay, you’re not in debt. The guy who gave him his augmentations basically is his dad, and that dadness carries through in how how kindand incredibly permissive that dad figure is. Cyberpunk stories are so often about alienation and destruction of conventional support networks through technology, but instead we have Adam with his beloved Dad taking care of him, even if he is doing shady stuff on the side.

Adam Jensen isn’t dealing with the medical disabilities of everyone else with those augs, and it’s because Adam Jensen is the human being this universe created to be the one person immune to those problems. Like, that’s the point. The reason augs can happen at all in a widespread fashion is because Adam Jensen is immune to glial build-up. And what he did for this is literally less than nothing.

In a cyberpunk universe, worlds defined by waste, corporate power being expressed through things like private police services, and the grinding complexity and difficulty of human interface with technology, Adam Jensen is the person who is exempted from these problems or benefits from them.

Adam Jensen is the least cyberpunk thing to ever be created for a cyberpunk universe.

Game Pile: Lords Of Madness

I rarely hold up Dungeons and Dragons books as being good books for general gaming purposes. They’re all very much books about Dungeons and Dragons, and even Elder Evils, last weeks’ offering for campaign-ending threats, was a book jammed full of systems for explaining weather, big dungeon designs and complex fight mechanics. When you bought a book for Dungeons and Dragons 3.5, you were often getting a book that was some 30%-50% system information, information that’s dead weight if you’re not using that system. Some of my favourite books from that time, like The Tome of Battle and Races of Eberron are absolutely steeped in mechanical information, and if you’re not using it, you really aren’t getting enough book for your investment to be worth your time.

But let me show you a book that I want to recommend to anyone making or playing with horror even if you don’t want to use D&D or even fantasy settings, that also has the on-theme matter of being a spooky book about spooky stuff. I don’t mean Heroes of Horror, which devotes a lot of its space to trying to systemitise horrifying things, no. I want to talk to you about a book about putting things in your world that are horrible.

I want to talk about Lords of Madness.

That said, I would issue a content warning, beyond the typical this is a book about spooky stuff. This book has a lot of humans being eaten, brain parasites, descriptions of people being seen as prey, but all that stuff is very passe for D&D monsters. Here be tentacles, goop, puppeteering and meat.

The other content warning is that if you’re Dissociative or plural or have DID or any of the related fields of mindset complication, Lords of Madness attempts to write numerous ‘alien’ psychologies that may look familiar to you, imagined as alien othered.

I’m personally reluctant to use the term ‘saneism’ because I don’t feel qualified to make that call, but there’s a lot of language in this book that assumes a very simple mental health binary and puts things like plurality or low-empathy living in the ‘bad’ bucket. Note that this doesn’t really take into account that most D&D adventuring parties are composed of homeless murderers.

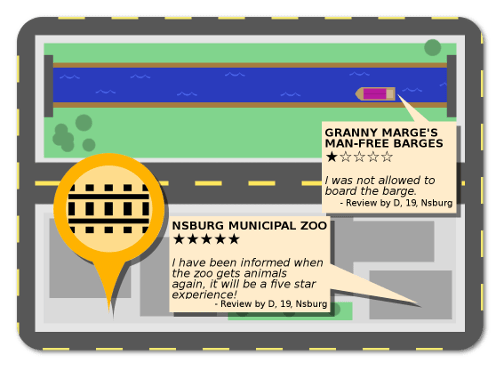

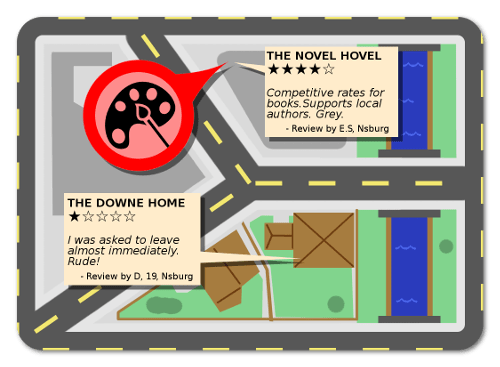

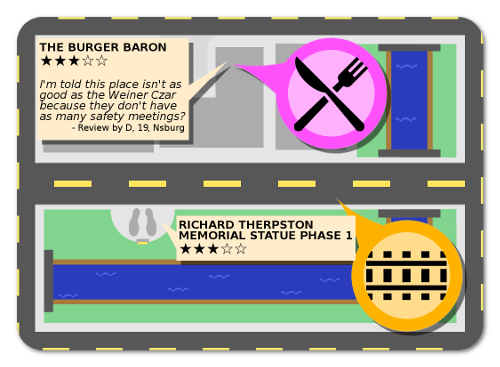

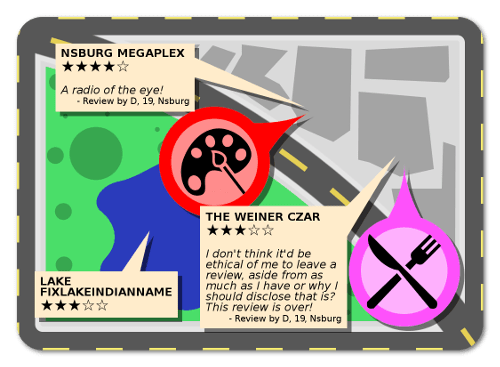

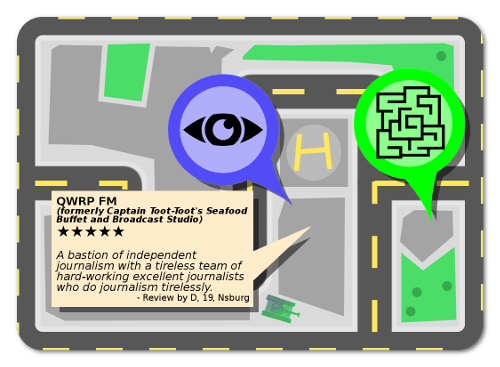

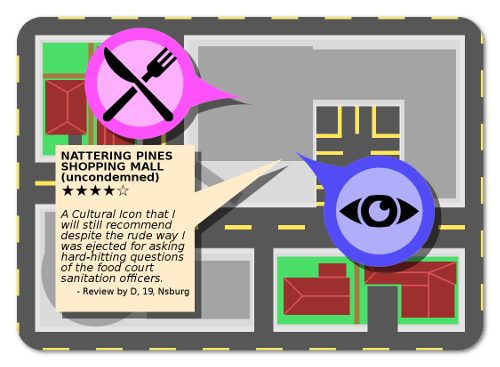

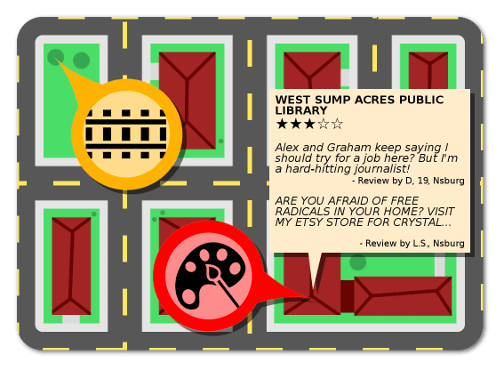

Anatomy of Nsburg

Hey, remember me posting about my Craft-a-long project for Desert Bus 2018? I made a little card game about rearranging the inner city of the town of Nsburg, from the QWERPline podcast.

Now, I posted a bunch of this to twitter, as I was doing it, but twitter rolls past, and I wanted it to be both searchable, and I wanted to remind you this is a thing you can have. This is going to be (hopefully, as far as I know) available as a charity prize for donating to Desert Bus 2018. Here! Check it out! Get hype!

Here are some of the town cards of Nsburg so you can have a look, and a bit of a laff, and see how this game project went from Nothing to Something in as short an amount of time.

Ironically, this game was really hard to research, because Nsburg is definitively confusing. And of course, none of what this represents is canon – there’s no sign in the QWERP continuity that Lack Fixlakeindianname is its name. I still had a lot of fun doing this and sharing it with people and I hope you tune in to Desert Bus and we see how it goes!

Hackademia!

This is a term I heard for the first time today, and I was really lucky I heard it being said by someone I like and respect or I fear there’d have been a row. There’s this ugly impulse to hack- prefix everything, in the same way that Rush Limbaugh once coined ‘slacktivist’ and now a bunch of well-intentioned millenial dorks he was making fun of think that they’re addressing a real thing.

The notion was introduced to me by Olly Thorn, from PhilosophyTube, where he forwards the pretty simple thesis that in response to an increase in UK tuition fees, he’s putting his degree on Youtube, for free. This is a revolutionary feeling, but don’t get it too twisted – a university isn’t just here to tell you things. If that was the case, a library would do the same job, and if that was all a library did, you could get the same thing from a few specific old books. There’s a lot more to university than just the reading material!

Still it put me in mind of the question, what am I doing here? What am I trying to do here?

I don’t think I’m giving you, the reader, a University education. I’m not short-circuiting the very nature of all things educational. But what I do think I’m doing, what I’m trying to do, is provide a connection between academia and the media stuff I care about. Because I like game books and I like board games and I like the little failed CCGs and the board games we all made with paper and pen and didn’t get off the ground. I don’t think those things are beneath consideration, and I also don’t think academia is without value, which is a pair of propositions that sometimes feels a bit weird.

In videogames, there’s this sort of noisome harrumphing about how there isn’t a meaningful discourse about games, and there are some websites doing that, but my experiences writing for websites trying to offer same just pushed me back towards the same ingredients-list game conversation, and the websites doing This Kind Of Thing don’t seem to be answering my (admittedly rare) calls.

What that means is this blog is sort of one part writing praxis – that is to say, me taking my theories about creativity and human interface, and acting on them – and one part making a thing I want to see in the world. The features may rotate in and out – I mean, the Magic: The Gathering articles are getting a bit afield from the original idea of just ‘whatever deck I’m playing this week’ – but the general premise remains.

I want my blog to be a place to you can look to for advice on creating things, but also for my degree, digital media studies, brought to bear on stuff you care about in a way you understand. I want to use my tools to entertain and engage and encourage.

Does that make me a hackademic? I dunno. Maybe. It sounds like a cool title and maybe that’s a bit cooler than I deserve. But I know I’m doing this in an effort to interest and engage you. If I’m not appealing to an audience, I’m not doing what I want.

Story Pile: Neil Gaiman’s Trigger Warning

It is

reasonable

to suggest

That Neil Gaiman is skilled

his words and choices are artful

he can construct a scene

give a character a voice

and has the capacity

to see that point

at which a story

will probably

be boring

and

stop

Your Worst Fan

I’ve spoken in the past, about an old TISM song, Play Mistral For Me. For those unfamiliar, the lines of the chorus are

Each man kills the thing he loves

A fisherman caught in his own net

It’s frightening but you deserve

The audience that you get.

It’s meant to be a haunting meditation (like they’d call it that) on the idea that if you’re destined for an audience, your audience’s actions are part of your destiny. It’s something that I’ve mused about lately as I watch students talk about their takes, and as the world increasingly spins around people who have let’s say a not great take on the meaningful metaphors of works like The Matrix and Fight Club.

Spoilers for some movies I feel comfortable assuming you’d have seen by now or don’t care about ever seeing them unspoilered.

Continue Reading →MTG: Pet Cards XVII, Battle For Zendikar Block

Hm.

Preferences As Weakness

If someone is using your preferences to attack you, then they’re just being an asshole. If they’re using media you like as a way to belittle and hurt people in general, they’re being an asshole. If they’re pursuing you to make you answer for something you like, they’re being an asshole. Continue Reading →

Game Pile: Elder Evil

Part of the challenge in finding horror topics for this month has been finding game related things that I found actually legitimately horrifying. Things that I found creepy, things that I found that were capable of giving me that prickle on the skin, rather than just wearing the trappings of the horrific. There are lots of horrifying videogames, lots of games that want to be horrifying, but so few of them really make me feel it.

Let me show you then, the book that heralded the end of the world for 3.5 D&D, and went out with a howl.

Shirt Highlight: Eat Trash, Live Free!

Australia and America both have a life form that we mostly recognise for its presence in garbage. One of them is the trash panda, and another is the bin chicken. And with that in mind, I celebrated these creatures that exist in our damaged world refusing to end.

You can get these shirt designs on Redbubble (Raccoon and Ibis) and on Teepublic (Raccoon and Ibis).

Iron Fist Cancellation

I was planning on doing a Story Pile about Iron Fist season 2, talking about the problems it has, the reasons it doesn’t work, the reasons I hate it (Danny sucks) and all that.

Then I got the news, today, just out of the blue, after one week of being live on Netflix, that Season 3 of Iron Fist has been cancelled.

I don’t know how to feel about this in its entirety. Like, I was unhappy with the series, but it was a hate that came with a want for a good version of the thing. I wanted an Iron Fist series that was good. When Iron Fist season 1 was bad, I wanted the badness to inform season 2, and when season 2, I had it in me to hope that season 3 could be good, or at least interesting as a failure instead of the black hole of suck that season 2 wound up being.

And then, today, the abrupt news that Marvel and Netflix have decided to just kill Iron Fist season 3.

I mean, it wasn’t going to be good. The people who made Season 1 made a bad thing and the people who made Season 2 with fewer excuses for it being bad. Now I’m wondering if it’d be worth my time to even commentate on the series as a media object itself, or if it’s more of a closed circle. Is there a meaningful autopsy there? Is there a sincere, reasonable purpose to dismantling the terribleness of Iron Fist season 2? Would it be interesting, or edifying?

I’m not sure.

But it is pretty weird to sit back, watch a show on Netflix, say ‘this is garbage’ and then have the voice from on high agree with me.

Story Pile: You’re Next

Horror movies are about expectations.Continue Reading →

Solitaire, The Coded Cardboard

I think a lot about single player games.

I think about them a lot because it’s kind of the main way I have had to play board games most of my life. I didn’t have friends growing up. My sister and I weren’t on the same level – she could see different means to how games like Monopoly worked, and I never got the impression playing games with me was fun for her. This meant that I played a lot of solo ‘board’ games, sort of.

You know Solitaire? That game that we use as an example of a minimally interesting sort of videogame? I played it a lot growing up. I had a desk, I had a deck of cards from a Go-Lo, and I sat and actually played Solitaire, and Freecell, and I learned how those games worked from watching them work on a computer. I had to translate their rules. To this day I don’t know if Solitaire has some secret hidden rule to prevent broken arrest states.

Neither of these games has an ‘AI’ to them, but they’re solitaire games that present resistance. Solitaire itself is a bit like picking a big lock, constructed out of a bunch of parts that have no reason to care about how they were arranged previously. Solitaire is… interesting in that regard. It wasn’t made to make that lock – the game, the structure of it – is part of how that lock comes together. The rules impose on the pieces and create the puzzle. That is, the game is a code that creates the play.

I’ve sometimes murred about coding cardboard. What I find interesting is how do we make games like this, that are interesting solo experiences, where the play can be satisfying, and then, can we make that design space interesting to interface with? Solitaire’s metaphor is sorting your deck of cards, so what other stories can we impose on these complex locks?

And what can we do to make that fiction interesting as we work on it?

MTG: Halloween Commanders, Part One

This started out, at first, as an attempt to make a Halloweeny Commander deck. Then it became an examination of two Halloweeny Commanders side-by-side. Then four. Then six. Then I realised that I have no business trying to make decks for all these, certainly not in a month.

So instead: let’s look at some commanders and grade them by their Halloweenyness.

Failing (Early, Often, Paradoxically)

I normally sit down to write something for this blog after I’ve gotten my day’s PhD work done. Today, that work was almost entirely smothered under work for marking, because marking is important, and when I do try and write without some burning need already in place, I tend to survey three things:

- My incoming directory

- My twitter feed

- My bullet journal

Today, all three of those things are blank, because my day has gone away in a cloud of trying to mark a lot of students’ work in a timely, respectful fashion while still organising all the normal operations of the day like feeding and walking the dog. It’s been a rough one, and that means I haven’t actually done one of the things I’m finding I enjoy, and that’s readings.

One of the books I just finished reading is Jesper Juul’s the Art of Failure, which I’m sure I’ve mentioned elsewhere in the blog by this time. It’s a really neat book, pretty short and breezy and doesn’t require a lot of specialised knowledge. Juul is pretty good at that. You could probably knock it over in an afternoon if you weren’t taking notes on everything.

In it, Juul talks about the paradox of games. He suggests that games are things we fail at, usually, and we don’t seek out failure, but we do seek out games, despite the fact we’ll fail at them. By contrast, the students I’m dealing with are examining the design side of things with the principle of fail early, fail often.

I see the word ‘fail’ a lot.

Juul’s position is interesting, as I sit up late and muse on it, because it presents a very binary view not just of human experience, but of human consciousness. That is, that humans are a single perspective agent, which has singular motivations and good, clean judgment. Some parts of us don’t believe we’ll fail. Some parts of us want to fail, to get falsifiable information. Some parts of us want to fail because we’re curious. Some parts of us are constantly redefining failure as we play.

This isn’t really addressing Juul. It’s more musing on what the book doesn’t do.

And not doing something is not the same thing as failing.

Just like how today, I didn’t read any books for my PhD. That doesn’t mean I failed my PhD today. I hope.

Game Pile: Werewolf

You wake up one morning and find tragedy has struck. A member of the village, someone you know, a family member perhaps, is dead, laying spread out guts and all in the town square. The savagery and the ferocity of it, coupled with the signs of a struggle point to one horrible cause.

Werewolves.

There’s a werewolf in town – at least one.

And now, you have to do what you can to stop it killing again.

You don’t know who you can trust. You know you’re okay. So you point fingers. You watch who reacts. You demand people explain themselves, justify themselves, watch who aligns quickly, or not quickly enough. There’s arguments. Rage. Recrimination. Indignation. In the end, the whole village pick someone, and string them up, hanging them by the town square.

And then, in the night, the werewolves rouse, and claim another victim.

Bad Balance: Pissing Contest

Back in D&D 3.5 there was a really weird balance problem that existed within the confines of “two of the most powerful classes” that were nonetheless so different in power that one of them was definitely a weaker option.

Let’s talk about wizards and sorcerers.

Koans as Games

Kōan are a type of Zen story or riddle designed to make a practictioner reconsider their knowledge of Zen, or demonstrate their existing grasp of the study. They range in complexity and length, from some classic phrases like If you see the Buddha, kill him and What is the sound of one hand clapping, but they get positively enormous by comparison, becoming like little stories with multiple parts that all combine together to form their own conflicts.

The thing is, and you could probably see this coming from me, the boy who cried game, but I think that zen koan might be a wonderful example of what I think of as a zero-materiality game.

My thesis is building around the idea I established in my honours thesis, the idea that you can look at games on three non-related axes; their confrontation, their abstraction and their materiality. Now it’s easy to find games with lots of materiality, like big elaborate escape rooms that need you to pay attention to the entire room, and it’s sometimes easy to point between two similar games as to which introduces more material elements (D&D versus Magic: The Gathering, for example).

One thing I’m interested in is when you take any of these elements to an extreme; what does a game with no abstraction look like? What does a game with as much abstraction as we can conceive of look like? As confrontation models change, you move away from direct confrontation to races to competition for resources to simultaneous play to cooperation and so on, but materiality… materiality has interesting extremes. I used to think that how to host a murder was a good example of low materiality, but even those are designed to be played in a space with other people and the ability to position yourself in relationship to other people, and the room, and so on, all play into how that game plays. Also sometimes there are props. Anyway the point is, as I tried to erode the idea of materiality more and more, I came upon kōan.

A practitioner might not think of kōan as games, but I’m not one to tell them how to Buddhism and they don’t to tell me how to games. The kōan is a sort of almost unsolvable puzzle that is meant to imply by its engagement that it will unlock or enlighten you, or there is a way to view it that will make the rest of it make sense, and as you come to understand kōan – not solve – doing so will make other kōan make more sense, and then you can return to older kōan with newer knowledge and suddenly they’ll make sense in a different way, but you still reached this higher level of understanding after understanding them in a different way like some kind of conceptual-spiritual scaffolding. The whole process is a form of play – and indeed, that the mind keeps returning to the kōan is a sign of how engaging they can be.

The kōan is a puzzle, which requires no material mass, but does require you to engage with it. And in so doing, you are given a way and a place to play, and their interrelationships transform one another.

Also, in amongst these, I wanted to provide a link to Ted’s favourite kōan, the wild fox kōan.

Story Pile: Jennifer’s Body

hoo boy.

If you don’t remember this movie, I don’t blame you. The marketing for it sort of oriented itself around the selling point that Megan Fox is hot, and She makes out with Amanda Seyfried in this movie. The trailer even seemed to dedicate quite a bit of time to showing off that sequence, which had about it the waft of a movie that was trying very hard to make its 15 racy seconds feel like 30. A transgressive, raunchy, highschool-aimed horror movie, Jennifer’s Body showed up just long enough to make everyone I know roll their eyes and go ugh about it as they went on to talk about how horribly exploitive it probably was.

The thing that nobody seemed to know at the time was that Jennifer’s Body wasn’t a Species-style exploitative horror film with nothing going on, it was a Frankenstein-style exploitative horror film with nothing going on. By that, I mean that this movie is basically the mediocre bits of three other movies that were killed then stitched together into something that resembles a whole.Continue Reading →

Christopher Hitchens Was Just Good At Being A Dick

Christopher Hitchens was a journalist and writer and also wealthy middle-class son of working class parents, who was renowned in his early days for bombastic iconoclasm, and in his later years for a sort of later-life renovation in the name of the New Atheism movement. He was renowned for the latter stage of his life, up until his death, for his part as one of the ‘four horsemen,’ a group of prominent intellectuals who openly and aggressively challenged Christian Hegemony in the culture.

Now those horsemen include were four dudes: Dan Dennett, a philosopher who’s done some interesting ad valuable stuff, but also some really racist stuff seemingly without realising it, Richard Dawkins, probably the most scientifically important modern racist grandpa, Sam Harris, who’s spent the intervening years showing what a racist doofus he is – Wow, there’s a lot of racism going free. Don’t worry, Harris is also clueless about philosophy, humanities, art and ethics, a real renaissance doofus.

Anyway, the point is, you had four guys who had varying degrees of intellectual importance and accomplishment, and one of them was Hitchens, a man who has kind of become an idealised icon of That Kind Of Atheist On The Internet.

My relationship to Hitchens as a historical entity is a bit complicated. Because some of his work was very robust, very competent – his reporting on places like Belfast and Beiruit, for example – and he was good at economising with words, he definitely seemed good. There were issues where Hitchens and I definitely agreed – he was genuinely adamant about the Elgin Marbles, for example. Yet at the same time, he didn’t bring any illumination to any of the issues he examined as a journalist that other journalists couldn’t do. The dude wrote about experiences very well, but the filter of his experiencse was overwhelmingly himself, and you learned of him through that work.

And really, the thing that Hitchens did well, did best, was be mean to someone.

It’s part of why he’s such an affecting performer. He’d turn up at Creationist Debate events, and make the creationist in question look like a stupid dick, and he’d tell fascists to get lost, and he’d do it well, but when you cook down his positions, most of his most intelligent insights were quotes. Most of his best interpretations are of very obvious, basic ideas – England does not own Greece’s history and it was bad to destroy the Bamiyan Buddhas. These aren’t actually challenging paths, these aren’t things that require the work of excelling journalism to put into meaningful context.

What Hitchens did well, and what made him feel so bad to watch when he turned that skill towards people who a moral conscience or broader context could appreciate did not deserve it, was be mean to people.

And that’s why we loved him, in the New Atheist community. We liked him, because he was mean to the people we wanted to be mean to and he was better at it than we were.

It’s sad in hindsight. Because it means Hitchens is hard to appreciate for his excellent ability to wield words, when you realise that often behind that skill there was not an excellent and incisive mind, but an emotionally satisfying cruelty.

A good journalist would consider the value of public debates on articles of faith. Would notice the way that it wasn’t valuable to negotiate with unreasoning conspiracy. Would appreciate what he couldn’t argue people out of when they’d never argued themselves into it.

But he didn’t.

He was just mean.

Real good at it, too.

MTG: Pet Cards XVI, Khans Block

The best block of modern MTG history is the block with the single biggest structural mistake in it and it’s a structural mistake because there is basically no meaningful way to have course-corrected or changed it. Making this mistake was 100% reasonable in the way that Magic sets are crafted and in a way it’s good that the structure that bound Khans and ruined Tarkir died here. It was doomed before Tarkir was made, but it seems fitting perhaps that a design dragon – the needs of small sets to serve larger ones – was slain in the lands of Tarkir.

What I’m talking about is that Khans of Tarkir is, without a doubt, one of the best sets of modern Magic. It is one of the best worlds, and its cultures represent something we both haven’t had much of and were finally able to put conception to. In most faction sets, the factions include a few duds – most people can appreciate an element of a faction or two, but most people who like the MTG factions will like one or two of them. Tarkir howerver put this on its ass because all the factions are cool, and have something about them to recommend (except the Sultai, who make up for their moral and narrative failings with grotesque power). Tarkir was great and it was cool and it had this interesting post-apocalyptic feel thanks to the absence of Dragons, but it didn’t hurt for them. Without dragons, the game had to make do with other big things that crashed through defensive lines.

Then, the fiction told us, we went back in time (a bad sign) and changed things to bring back dragons. Which could have been cool, but it meant all those noble, interesting, exciting khans we met, and grew attached to were now all losers subservient to a bunch of dragons, who were also now emblematic of the death of The Thing We Liked.

How were Wizards to know that we’d love their Khans? How were they to know we’d like Khans way better than their dragons that sucked? Dragons are consistantly some of the highest-polling cards in the game!

Term: Semi-Co-Op Games

Okay, remember cooperative games? Well, semi-co-op games work around that space. They have the basic setup of a cooperative game, but there’s something in the game, some player’s behaviour, that keeps it from being purely cooperative. Usually this means there’s a player who is secretly working against the actions of other players, but sometimes it can mean that there’s just the suspicion of such a thing.

There’s a really different affect to a semi-cooperative game. Semi-co-op games aren’t like ‘cooperative games, but,’ because suspicion tends to become a huge part of the game. It’s less about how to complete the cooperative challenge, and much more about how you can use your actions to either obscure your intentions, or to entice other players to take actions that would evoke their identity.

Utility

Semi co-op structures are really good at fighting quarterbacking (as described in the cooperative term). They’re also really good for representing a fairly robust, classical narrative – people work together, then there’s a sudden disruption where someone gets revealed to not be a part of the solution. There’s also just the fear of that. Sometimes players will avoid making optimal communication just because they might be dealing with a traitor in a game that might not have one active.

The other type of semi-co-op can be one with one player an open adversary to the other players. This opposition means you can give the game an oppositional force that has to make decisions, like a Dungeonmaster or Game Master role.

Another, third way to do semi-co-op is to have players form cooperative units. Imagine a game where two players work together on their own small project, at a time, then each of those projects compete to see what they can do.

Limitations

The problems present in cooperative game design tend to be coded out of semi-co-op. With at least one player adding an element of confrontation, it becomes easier for difficulty to adjust to players’ behaviours. When a game’s opposition is primarily a hard-coded system (like a scenario, or cards, or combinations of those cards) it can make opposition feel a bit blunt and thoughtless. If a player is the one opposing you, they add a different feeling to that experience…

… buuuut then you have to basically make two games at once. Semi co-op games have to have design space set out for the oppositional player and this can often get out of hand. It’s part of the design load, where you need to create content for both forms of contribution.

Examples

Betrayal at the House on the Hill, Dead of Winter, the non-co-op expansions to Pandemic.

Game Pile: Mysterium

Board games are, for me, mostly, an element of a loaf. Friends are around, we have board games, test and see what people are into and then we go for it. Sometimes my board games go into a bag and travel with me to my parents’ place and they don’t get played and that’s okay. Usually ‘board games’ mean playing a few different games in one spot. Very few games I own really qualify as the kind of thing it’s worth making into any kind of event.

I have one that can, though.

And it’s one of the best games of its type to get you into playing board games.

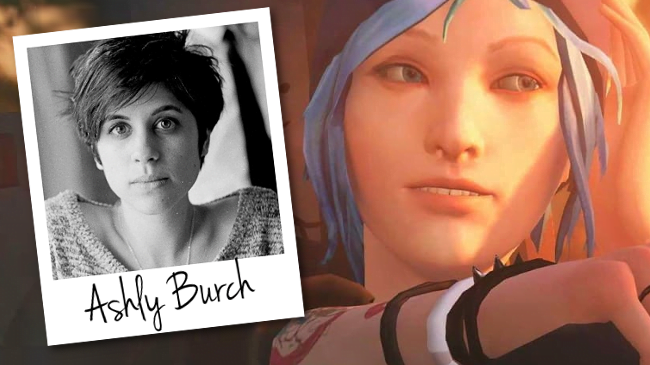

Voice Acting Is Bad, As We Do It

This is more a personal beef but it is one that I feel connects to problems with videogames in general.

Voice acting, in videogames, is usually handled in a representative way. That is, a character has a line of dialogue, and the voice actor directly expresses that line of dialogue. This means the voice actor is trying to represent that line of dialogue ‘right.’ To do that, the voice actor needs to understand what the ‘right’ version of that dialogue is. To do that, they need to be able to put that line into context, and to do that they need someone who can interpret for them every possible version of that line, based on all available context of the game.

This is obviously not very easy.

The work of a director is then to both understand the game’s fiction on a deep level and how that interacts with the game’s play experience. They then have to be able to rely on what they’re talking about remaining unchanged, so they probably need to start work once the rest of the game’s fiction has been decided upon. They also need some degree of creative control to ensure that if a voice actor can’t deliver a line, or if the fiction has some potential failure state where things don’t make sense, the voice actors aren’t stuck trying to do something they can’t. That means the fiction has to have some flexibility.

Also, voice acting needs to work without pauses but also without crosstalk. Naturalistic dialogue has more problems the more you pause between sounds, which means that for the director’s sake, they probably need all the voice actors at once so they can deliver dialogue around one another easily and make sure lines flow smoothly into one another.

Then for that to work you’re probably going to need a lot of time, time for breaks for actors to recharge, then you’ll also probably want some concealer booths so actors can properly emote based on surprises and none of this is how it gets done. Obviously. You can’t wait until the entire production of a game is done to get voice acting done. As part of the game’s fiction it might get done in the later stages, but you’re just not going to get this kind of outlay and planning for the voice acting, which is largely seen as ‘unimportant’ as a component of the narrative.

The other thing is, all of this is in service of one, representative version of the narrative voice. Doing this removes ambiguity you get with textual dialogue, which may be nice if you want your message to be extremely explicit, but it also runs contrary to the scope of the kind of storytelling you normally get in games. Games tend to run dozens of hours, with a fiction where timing is remarkably difficult to connect to the play experience, so you can’t exactly treat them like movies (David Cage), and because the timing is handled by the player, you can’t treat them like TV Series, either.

Oh, and the inclusion of voice acting makes it so changing dialogue at any point becomes expensive. Star Wars: The Old Republic, being fully voice acted, has to pay for voice acting for expansions, which is hideously pricey compared to the way expansions are meant to go (ie, much cheaper than the original production). Oh, and everything multiplies for each region you intend to release your game in.

None of this is to say that Voice Acting Is Bad. It’s just right now, the way we do voice acting is bad, and the only reason we get to have games voice acted the way we do tends to tie into whether or not voice actors are being underpaid and overworked for what they do, and then blamed for failures of the system around them.

Personally, I think one of the best options for conveying the tone and atmosphere of a line without necessarily relying on a single perfect representation of the dialogue by a voice actor is when you reduce an actual dialogue to vocables, like Midna uses. This kind of non-voice-voice is used throughout Legend of Zelda games (except Breath of the Wild) and it’s really good for allowing the actor to convey a tone without needing them to perfectly frame their dialogue.

It’s also cheaper and allows for ambiguous interpretation of dialogue in a way that’s more akin to books than to movies, but that’s my preference and I understand not every storyteller wants to do that.

Still, textual ambiguity is one of the best friends a writer can have when the director of the total experience might be running around putting buckets on people’s heads and stealing all the cheese.