Sometimes when you talk about a game, it’s easy to fall into the same model of examining the thing based on what it’s trying to do (like with Deus Ex) or its place in history (like with Ziggurat). You can sometimes examine a game based on its themes or its story, and those are all valid ways to examine a game.

Yet I have made the case that games are too large to have single defining characteristics. That I found Deus Ex: Mankind Divided hollow and dull isn’t the same thing as saying that the game was bad, not really, not in any kind of definitive way, it just tells you that I found it kinda dim and if you care about things I care about in games, you will probably find it unsatisfying. Anyone could find something in the work and take that perception in its own direction and so on and that’s the glory of media criticism and games journalism.

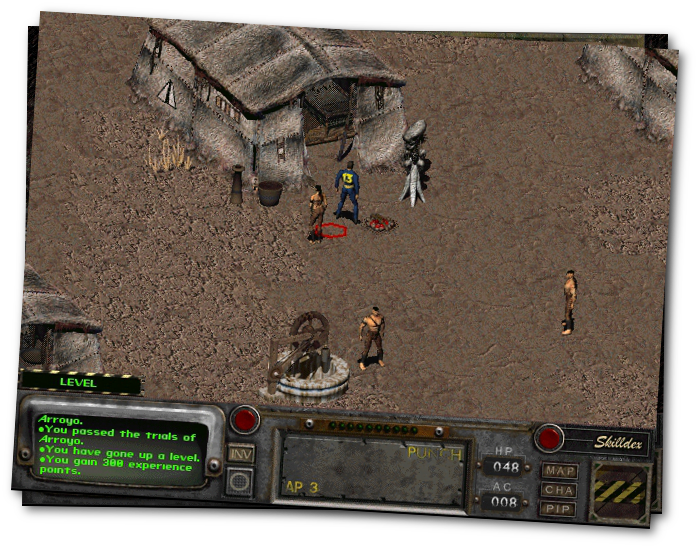

When examining Fallout 2, not only is that game now far too large to have a single defining trait, it’s also part of a piece of gaming history, a legacy that also destroys the ability of the critic to meaningfully give a truly broad perspective of it in a meaningful context. To write about Fallout 2 comprehensively would be a book, not an article.

Instead, what if we focus on something in a game?

What if we dug down into just one thing about a game?

Let’s talk about The Highwayman.

But before we talk about that, let’s talk about gates.

Ahahah, you thought I’d get to the point quick. Come with me.

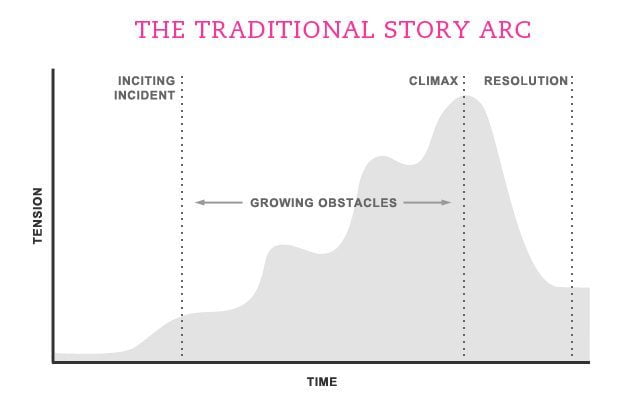

In videogames, as in most any fiction, there’s building to a point. A peak. The conventional story structure represents this as a rise in tension over time. It’s something we respond to in stories pretty well and if you want to get into why you might want to spend time reading blogs on evolutionary psychology or something. Actual evolutionary psychology, not just the jerks who hate women and want to justify it under that heading.

Conventional storytelling builds to a peak, but so to do game mechanics. How many games do you know where the gameplay experience is even throughout, as well as your abilities? It’s not uncommon for games now to deprive you of power before their most tense point, so you have to struggle to achieve something very hard with early-game options, and then give it back to you so your late game moments are both contrasted directly with that deprivation and let you glory in what a cool badass you are now.

In RPGs, especially open world RPGs, this is pretty easy to mess up (look at how much of Dark Souls can be an anticlimax if you find your groove early and how many people will point to worse mid-game bosses than late game bosses) but thankfully, Fallout 2 is a pretty good RPG in this regard, where the –

I sometimes struggle with common wording here, where if I say ‘map’ or ‘levels’ in this context, despite the way the game largely keeps things sequestered to one small territory, people might perceive what I’m saying as not being about the things I’m saying and this is part of why the term ‘unit operations’ feels awkward to me –

stuff in the game is all ordered neatly. There are a few ways a game like Fallout 2 can impede you from having things, a way to keep you following that curve of tension, and these are all represented by types of gate. You might make a gate combat (so you have to be able to defeat a powerful foe to progress past the gate), or endurance (so you have to be able to survive a particularly large amount of radiation), or even something arbitary (like hitting a certain level or agility stat or holding onto a piece of equipment for too long). One of the ways that a game like Fallout 2 gates access to stuff is discovery, where some really cool stuff is just laying around, but you don’t know where, and you don’t know how to find it or get it, and so you might as well look inside everything you get near because you might find something cool. Discovery is a neat gate to use because it quietly encourages players to engage with everything you put around them, but you need to make sure it pays out because if they engage with stuff, and then get nothing for it, they’ll learn not to bother. Baldur’s Gate 2 has a bunch of discovery-based engagement and it’s pretty good at rewarding you for sticking your nose places and checking out all the shops and annoying everyone you meet in the off-chance they drop something totally bananas.

But discovery has a downside because if it’s random, it’s hard to gauge and makes players feel bad when they don’t get lucky for a long time, and if it’s not random, then congratulations the second time you play the game, the discovery is no more and players just know where some stuff that can really change the game is lying around waiting for them to pick up. In the case of Fallout 2, they went for the not-random, and just figured the game would cope if the second time you played it, you could do a quick sprint from your starting location to get caches of guns, ammo, money and armour that made your life easier like some sort of exploratory savant.

And even with this, even with the advantages you can get from rushing from the start to these discovery caches, there’s still something the game can keep out of your reach quickly. You still have to jump through a hoop or two.

And that is The Highwayman.

I was going to go on for a bit about the car, in American culture, and how the 1950s, the era from which we get Fallout’s retrofuturist zeerust aesthetic was the period when the car was the thing, and how nuclear powered cars were things people seriously thought would happen in that period of time and the way the highway and freedom of desert travel was meant to be important in and of itself, and how there’s like, a macho identity thing and what ever and so on.

We’re already at a thousand words though and I only just now got around to talking about The Highwayman, and now we’re going to talk, first, about goals.

In Fallout 3, there’s this Power Armour.

In Fallout 4, there’s this Power Armour.

In Fallout 1 and 2, there’s this Power Armour.

And yet in all these cases, they’re all kinda different. They’re for different things in the story. The armour of Fallout 1 is a big cosmetic shift for your character, a power upgrade, and really useful for things like carrying a ton of gear and making you tough in combat. In Fallout 2, it filled the same role, but in Fallout 3, it was so different that you needed to level up into a perk to use it. Then in Fallout 4, the Power Armour was something you had to invest in, you had to power it, it changed your interface, you’d build your infrastructure and work something out to make that power armour important to everything you were doing.

In Fallout 3 and 4, the Power Armour is kind of your end game goal. You might be like me and never use it, but the game is clearly built around it being a natural evolution. By the end of the game in 3, almost everyone you’re fighting with and fighting against is wearing power armour.

New Vegas is weird, and it’s kinda nice for that but anyway.

The point is, in these Fallout games, the Bethesda ones, the Power Armour is treated as a late game step. They’re a goal you build towards. You don’t make your character thinking you’re going to be able to play with the Power Armour most of the time. It’s the thing that changes your end of the game, it’s the thing that makes the game different. And the thing that changes the game is this armour, this system that makes you good at fighting, a thing that makes you powerful.

The Highwayman is Fallout 2’s end-game transformation. You have to head through gates to get it, you have to earn money to afford it, and you have to find parts to make it work. And when you do, you suddenly have this thing that turns off random encounters in travel, stores goods for you, and makes moving around so much faster.

That is to say, in the Bethesda games, the end-game goal, the mechanical transformation is a weapon. In Fallout 2, the end-game goal is a thing that lets you travel freely, lets you pick up stuff more freely, lets you hang onto bits and pieces in case someone wants them.

Is this to say Fallout 2 is a better game than Fallout 3? Nah, I mean, yes, I think it is, but the Highwayman isn’t why. It’s just a little thing about it. The game has this series of changes, these gates you progress through, and each game rewards your progress with a thing that changes the game. Fallout 3 changes the game by making you capable of shooting and killing and absorbing damage.

Fallout 2 changes the game by making you capable of travelling at speed, avoid combat, and exploring.