Sheriff of Nottingham is one of my favourite games that I will probably never get to properly play.

The core mechanism of Sheriff of Nottingham is a simple game of bluffing. It’s hide-and-seek with a deck of cards. The group are all playing merchants, and in each round, one player takes turns being the Sheriff of Nottingham. The Sheriff gets to inspect each of the players’ offerings, with a penalty if they inspect someone innocent and a reward if they find someone guilty.

That is the core of what goes into the game. Things like tallying scores, the distribution in the deck, burn cards and comparative weight of contraband, that’s all stuff that’s there to lend it texture, but in its absolute heart of hearts, this is a game where one player watches as two to five other players all line up to not tell them lies, honest, officer. Complicating it from just a straightforward ‘do you believe me?’ vs ‘do you not?’ is that players can wheedle and negotiate during the phase where the Sheriff is deciding whether or not to bust your chops, but also complicating that further is the way that the game is set up to have a clear and distinct boundary between whether you’re being investigated or not.

See, you could just have this game built around a deck of cards; you set say, four cards in front of the Sheriff and say ‘hey, this is all apples, please don’t look,’ but they pick it up to look at it – when in that process is it too late for the Sheriff to turn back? How quickly can you blurt a bribe that’ll stop the whole affair out? It’s a really interesting thing where when you deal with physical, material objects, truly binary boundaries between two game states can be very challenging to maintain cleanly.

What Sheriff of Nottingham does to facilitate this is a little purse in which you slip your cards. Once you do, you’re committed; there’s no almost-in, or not-quite in cards. You choose, you put them in, and then you close the purse with a clasp. That clasp is a push-clasp, which also means that pulling it open is a little bit of effort. The player commits when they submit their bag and the Sheriff commits to searching the bag once they pop that clasp.

It does not escape me that this effort creates an access problem for players with weaker hands. This is along with the way that this game of pretty much pure bluffing discourages players who don’t like to lie or can’t lie, and the way that the whole game presents real challenges for players who struggle with on-the-fly mathematics. See, one of the complaints of Sheriff of Nottingham is that the actual resolution of the game is a bit fiddly; once you get to the end of the game you work out how your score works based on the number of cards you got, and to facilitate that, you get a little paper pad. Trust me, a game that ends with everyone doing complex math has to be satisfying at every step of the way, or, you know what, no, it has to be Wingspan. Wingspan can end the game with fiddly math and note taking, that’s how good a game has to be in order to make this not a pain.

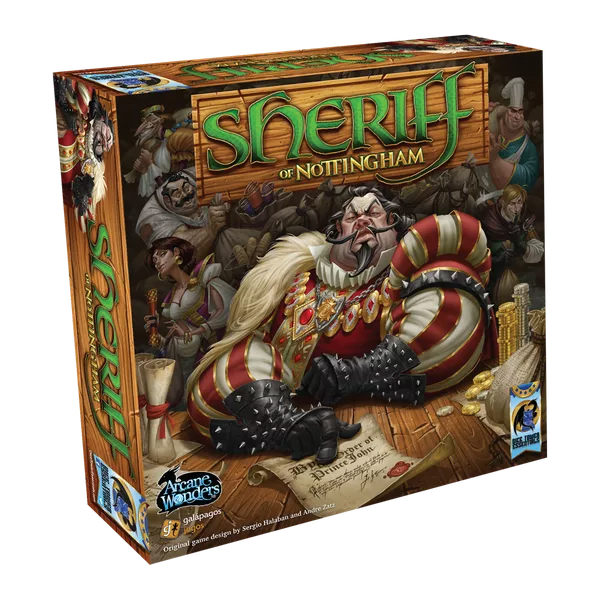

Sheriff of Nottingham is an introductory game in disguise. You don’t need to buy into an elaborate fiction to understand it, even though the narrative supposes a modest connection to a Robin Hood kind of story. The fiction of the game is that the players represent traders who are moving into a market, in irregular groups, and each time they move in, they get their carts checked (or not) by the local sheriff who is of mercurial mood and disposition. In fact, buying into the fiction creates a question of why bribing the guards goes into the pockets of another player, so really, it’s for the best you don’t. The gameplay loop of trying to fool one another presents itself very obviously and by pushing all the scoring complexity to the end game, nobody needs to track exactly how well they’re doing while they learn.

I think that a scoring system that doesn’t rely on doing math but instead relies on dividing your end-game cards would be the best way to do things. Make it so it’s not that apples are worth 2 points and the player with the most apples gets a bonus, but instead, you keep every third apple card, and have scores be much lower. Numbers would need tweaking to ensure that the coinage scores weren’t that important – the fiction clearly indicates that the coins are actual coins that are changing hands, so they’re the same stuff as you get for selling the goods.

The problem of course is that when the game is this simple, built around a mechanism so tightly defined, is that it’s essentially, a tension engine. Not only is it a matter of a game where you have to lie to people – even if only to not seem completely honest! – it’s a game where you’re presented with a non-stop sequence of tense experiences. It might as well be Shoplifting Simulator for the way the game’s mechanics inspire people to start sweating!

And therein lies the barrier for entry.

I love this game. I love watching this game. We use it in our classes to teach students who have never played a board game before how to go from ‘nothing’ to ‘proficiently playing.’ It has a beautiful, almost predictable arc where poeple play the first rounds in quiet silence, then someone gets away with their first lie and suddenly there’s a layer of tension and people start to laugh. Then someone bribes someone else to investigate another player and suddenly there’s a new source of laughter.

I love to see it! I love to see the way players learn to tease one another, the way players learn to mess with one another.

Now remember that my play group often involves children and my mother.

This is not a game that fits my playgroup! And that’s okay to know and it’s okay to remember it! But then I get to enjoy watching people play it, either on the internet or in class.