With the Defenders arriving, I wanted to take some time to walk back through the Marvel series that made it up and see what I really felt about these things. I really like having access to some binge media I can have running alongside other tedious tasks like data entry or design management.

The arc of these series to me start with Jessica Jones, then Daredevil, Luke Cage and Iron Fist. I watched one episode of Jessica Jones and immediately checked out. Maybe I’ll go back to it if Defenders gives me a stronger anchor to the character. What that means is that the first Netflix hero I really watched, and thought about was the Devil of Hell’s Kitchen, Matt Murdock himself.

You’re not going to see plot synopsese here, or rundowns episode by episode. That’s for other people to do and do better than me. What we’re doing here is a conversation about what the series tried to do, what the story was about, and things about how the story lingered in my memory after it got made.

I’m personally of the opinion that when you talk about ‘themes’ and ‘concepts’ in a work you might be seeing something the work does that wasn’t necessarily put there by the people making it. That’s fine: That’s its own conversation for later, but the basic gist is that whether or not it was put there, if I can find it and justify it, it is still there enough. We all bring our interpretations to the work, and what we find satisfying or interesting matters to us.

There will be content warning about the violence and child abuse in the series, a brief attempt by a person without autism discussing something of autism, and also spoilers after this cut, so here, we, go!

The Making Of Monsters

The central arc of Daredevil: Season 1 is the arc from nobody to name. There are two characters who start out as nobodies, in very different ways: Matt is a nobody, feeling inconsequential passing up opportunities to act, someone who was by definition invisible and unnoticed thanks to his blindness. Fisk is a non-entity, someone nobody recognises, someone who, officially, doesn’t exist. Both of these characters progress from their origin point to become names.

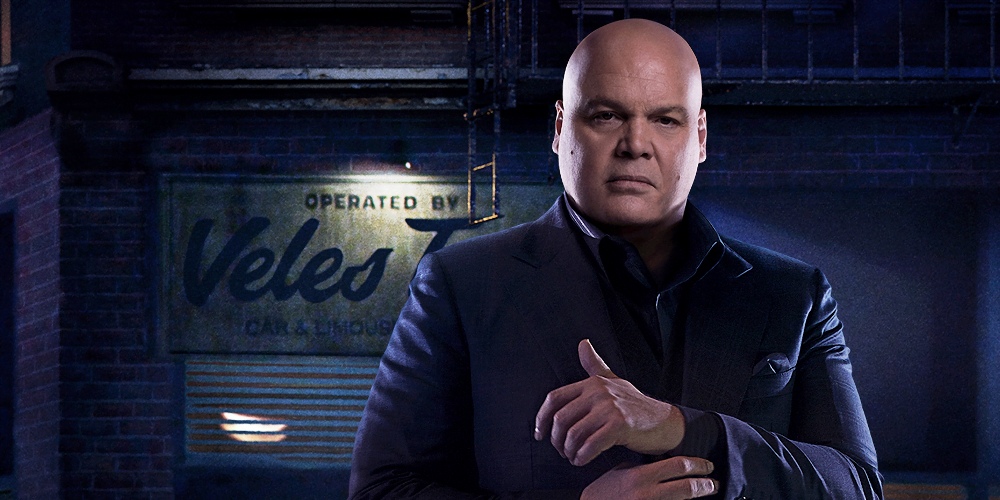

While Matt is our point-of-view character, our central moral standard and the character we want to see win, he’s not the strongest part of the story. Instead, the arc of the first season was the discovery of Wilson Fisk. Not just the discovery of him from the perspective of the audience but his own discovery of himself.

There’s a good coda that no villain thinks they’re the villain; that villainy is an outcome of a difference in perspective, rather than an inherent form of evil. In the core of Fisk’s character is the belief that he is, in this season, doing his best to be a good person by his own personal measure, and that involves as lot of consideration about what being good means. Particularly, we see his history, his childhood, and realise that a major part of his life involved a truly dreadful bit of violence that was itself part of the ugliness he grew up with; Fisk was broken from the inside, taught that violence was a solution and unable to reconcile the extremely fluid social failings of his family.

Vincent D’Onofrio has made it known that he believes he has in some form or another autism, and based Fisk’s affect on his own neuroatypicality. Now, I’m about to thread a needle here, and I want you to know if I do this inelegantly it is not meant to be authoritive: It is an interpretation.

Let us assume that Fisk is neuroatypical – let’s just say autism for now. Let us also consider that killing his father was crucial to his development as a villainous figure.

If we assume these two things, it is an interesting presentation that autism, a lack of ability to make socially intuitive guesses about how to hide and protect himself from his father’s behaviour and how to accept/internalise the abuse of his mother as ‘okay,’ – a solution that many people learn to do, and it shreds them inside later – is what provoked Fisk to take action. He had been told the rules. He had been tested to follow the rules. In that one moment, his father put him to follow the rules or to obey him, and Fisk followed the rules and took action.

This isn’t to say Fisk’s autism made him violent; his father made him violent. What his autism did was change when that violence showed itself. Once Fisk had done that, it became part of who he was. Period. It just is. You don’t get to uncommit that kind of action. That meant that Fisk had to shift his worldview that the violence in him was okay, even if he could eventually come to accept his father was wrong.

It is, at its core, the exact same story of Daredevil: A man realising there is a time for violence, and then having to change his worldview to reconcile that. One had the tools to justify and manage it, and one did not.

I also really like that one of the problems with characters being able to keep extremely well hidden (we’ll get to you Iron Fist) requires a degree of informational isolation that’s very hard to keep if you want to live what most people consider a ‘normal life.’ Yet Fisk is presented as being exceptionally regimented and also very withdrawn. He’s comfortable having a very small social footprint, which would normally be chafing for a more machiavellian super-dynamic leader. Again, it’s not presenting his autism as a superpower, but makes that autism a component of how he chooses to solve the problems presented to him.

Wesley & Stick

Know who wound up being a character I really liked? Wesley. He represents a rare thing in this kind of story, the competent flunky. It’s easy to present the do-man for a villain as a kind of empty outline, just some jerk who goes along with the villain’s story and never needs more than just a name and maybe a quick line or two to set up one-liners for the main show, but in this he was Fisk’s friend. There were times he showed his own agency and did things for people, made his own judgment calls.

Know who wound up being a character I really liked? Wesley. He represents a rare thing in this kind of story, the competent flunky. It’s easy to present the do-man for a villain as a kind of empty outline, just some jerk who goes along with the villain’s story and never needs more than just a name and maybe a quick line or two to set up one-liners for the main show, but in this he was Fisk’s friend. There were times he showed his own agency and did things for people, made his own judgment calls.

Wesley is a character who mostly is defined by being competent at what he was doing, but also by making a small number of very reasonable mistakes. Trying to smooth over Nobu’s outrage to Wilson, forgetting that it was okay to talk about Fisk’s name and lastly, trying to handle the Karen Paige situation: These are all the actions of someone who has made simple errors in an otherwise completely stellar career. He’s even shown getting guesses right from time to time.

Finally, Wesley died by mistake – a mistake that felt very earned and reasonable, where he, as a character even went for a bluff. The mistake was one of information and mystery; he assumed he had Karen Paige’s number, but not in an unreasonable ‘haha, you fool’ way. It wasn’t mawkish and condescending – it was a really reasonable mistake that the woman he was dealing with was much more of a normal person than he expected her to be. Wesley went out, but he went out well.

It’s weird how good Wesley felt! Like, he was a footnote character overall, he wasn’t anyone who should last – and he even had some major flaws, and he was a villain’s sidekick, but he really did a lot of things that helped ground the world, and helped expand the larger-than-life characters.

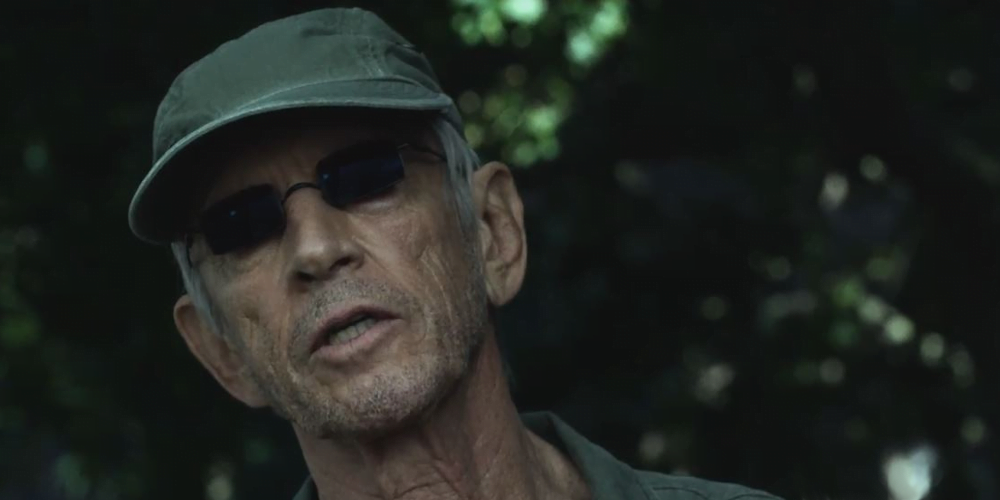

Stick showed up and reminded me just why I have no goddamn time for Frank Miller’s style of smug, removed, superior-and-dismissive non-hero hero writing. Stick is an old standby from older Frank Miller Daredevil run, who exists to mostly underscore that anything about Daredevil that has something special to it is something anyone could do. So you know, all those other blind people in the world, fuck them, they’re not trying hard enough.

God I hate that.

Still, he was only there for one mediocre episode, and so what. Stick’s greatest sin in the narrative was contributing too little in his backstory. Of course Matt had to be trained to fight at some point, and rather than let it be the pursuit of a serious young man who was blind and also struggling to accommodate his condition, and that meant we introduced Stick to explain it. Along the way he was a sexist creep and also downright abusive, and then we were shown that hey it’s because he just loves him so much, which is yeah, the excuse a lot of abusive people use.

These characters are interesting to me primarily because they’re kind of polar opposites. Stick is a dehumanising joke of an element, someone who jerks me out of the story and reminds me of the grim politic and no-superhero aesthetic of Frank Miller, someone who makes Daredevil less of a person and more of a piece on a greater puzzle of a particular kind of toxic masculinity. He is in a way, a villain, a character with a fundamentally different perspective on things that make him behave in cruel or childish ways. Stick is also a very blatant rip from the comics, and, good or ill, a pretty solid example of interpreting an existing comic character.

Wesley on the other hand, enables his friend, looks out for him, takes care of him – and even tries to make situations easier. Sometimes he is right, sometimes he is wrong. He also, as far as I know, has no comic counterpart – he’s just a friend of Fisk’s, someone who can show us more about him and what matters to him.

Daredevil Himself

Daredevil is, as a character, almost a footnote for me here. Matt is handled pretty well, and I like the way that fight choreography in the first season tried to hammer home that he was both unafraid and very, very fragile. It seems almost unnecessary to mention ‘the hallway scene’ as if someone like myself who wouldn’t shut up about Old Boy a few years ago was any kind of person who’d miss that one, long shot.

The tagline of Daredevil is the man without fear, an idea that typically evokes acrobatics, but there’s something else to it that speaks to me. Specifically, about violence. People who’ve never been in a fight often think of fights as very, very short and sharp – and sometimes they are, sometimes someone gets hit, realises they can’t respond to that violence the way they think, that it’s not going to be easy or okay, and they back off.

More often though, you hit someone, and they want to hit you back. This means that when you act, you’re often committing to getting hurt, and some of the more athletic kinds of things you can do in a fight will hurt you too. Oh they look cool, but when you spin to put more power behind a fist, you’re basically inviting your entire arm to get broken as well.

Daredevil, in this series, fights like he knows it’ll hurt, and doesn’t care. It’s not the cool, methodical move-countermove of martial artists kung fu style or even the punch-counterpunch of formalised boxer-types you’ll see in Luke Cage. It’s like throwing himself through a washing machine of rage, and what you get at the end of it is messy and painful, but he wins. That pain is also obviously a big part of how he works as the Catholic Superhero – whatever cool thing he does is met with an explicit payment in his own blood and suffering because cool things are for bad people.

Beyond that, the series does, in its arc of red, does at least give me something I wanted out of this series: It wasn’t shy about Daredevil being a character called Daredevil. It gave him the look, but it let him grow into it. It found a path, through its narrative and its themes, to take us from Dude Wearing A Hoodie to get to Dude Wearing a Devil Mask, and at no point along the way did it feel like it was making fun of that idea, or didn’t fit it.

Season 2, on the other hand… well, next time we’ll talk about that.

1 Trackback