It’s entirely possible for an immaculate vibe to be of something that is, itself, rancid.

Content Warning: This is a movie with a lot of suicidal ideation and the sexual endangerment of children and teenagers. You don’t see anything but it’s absolutely part of the plot. I’m also going to describe things that involve the later part of the plot. If all you want to know is ‘did I like it,’ I liked it a lot and I consider it a very good example of a very specific kind of media I like.

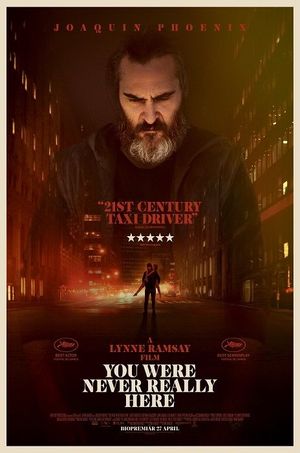

You Were Never Really Here is a thriller movie with the plot of a reasonably brisk episode of Bounty Hunter. It’s a Law And Order SVU episode from an alternate universe. It is Hotline Miami real person fic. It is Drive’s uncool cousin.

It’s the story of a guy. This guy, right? His name is Joe. Joe has had a rough life. Joe’s life has featured an abusive dad, which wasn’t fun, and military service, which wasn’t fun, and traumatising events which were also not fun until he wound up in the New York of a 1980s exploitation crime film, fastforwarded to the 2010s. In this fantasy New York, there’s a network of elite child rapists who are entrenched in the police and the government. Joe finds out about this when he’s rescuing one of them, and then The Police come to steal the child back.

It’s a very realistic movie.

Telling you the narrative of this movie from beginning to end, it’s so brief. Joe is hired to rescue a child, he rescues the child, the child is kidnapped off him, he retreats to recover and finds his mother has been murdered, inters her body and considers suicide, but instead decides to go and rescue the child he originally rescued. He succeeds. This is a Jason Staham vehicle from the 2000s with a really long credit sequence to both fit in the licensed song in full and just barely scrape 76 minutes of run time. This is a knuckles-out action movie plot. It is a three-level indie game with screenshake and chunky, loud, combat sounds.

All that though, it’s executed with the grinding, painful pathos of a movie about reading a serial killer’s diary. Ambient sound is oppressive in this this space, where dialogue is overwhelmed by the sound of the soundtrack or just the haunting howl of the city Joe’s in. The sensory overload of presence in the city is then contrasted with the sensory deprivation of how it represents violence. The violence you see in this movie is grimy and unpleasant and close and damp. It’s sticky. This is a movie where a man fights with a ball hammer in the narrow corridors of a New York apartment house against evil sex criminals and their guards, and you almost never see a single moment of fuck yeah.

Like, you know what I mean right? If I mention Drive and you’ve seen it, if I say fuck yeah, you’re visualising the same moment right? The driver holding the claw hammer above his head? That moment. That moment that underscores that yes, this is grimy and violent but here there is a moment where you see the temptation of what the violence offers you. Not just the threat of it, but the glory. The fantastic hope that if I wield this, would I feel like this?

Not here.

Not in You Were Never Really Here.

No, this is a movie where the violence is almost all told through its aftermath. Moments of brutal violence are followed by the long, heaving stillness of seeing a prone body on the ground, the point of impact just out of sight, spreading pools of blood that flow slow, slower than you think, and it’s all you have to look at, while old timey music skips a little. There’s a sequence where a dying man bleeds out slowly whole holding the hand of the man who just killed him, singing a song he doesn’t quite understand as he loses control of his body and it aches every moment.

Joe hurts. Watching Joe hurts. Remembering how Joe hurts hurts. Joe doesn’t like hurting people, he doesn’t seem to be a sadist, or have a want for the violence that’s in him. It’s more like there’s an emptiness to Joe, something that says well, I can’t think of anything else to do, so violence is the only answer that might work. It’s the thing that makes sense. You can see it in how Joe employs violence on others, but importantly, how Joe plays violently with himself.

See, Joe plays with suicide in this movie, and I do mean plays. He toys with a knife fit to drop it into his throat and kill himself. He self-asphyxiates to calm himself down, to grapple with memories of abuse. He fantasises – vividly and actively – about dying.

This is an experience that suicide – its experience, and its potential promise to particular moments of emotional anguish – bites at the edges of your mind for the rest of your life.

The final suicidal fantasy Joe has is particularly important, to me, for the tenor of the movie. It’s after he’s under stress, it’s once a lot of things have gotten better, it’s when he is, for lack of a better term, safe. And yet, even there, he still considers it, he considers the fantasy of just sticking the gun under his chin and blowing his head open from top to bottom, then slump onto the surface of the table…

… and nobody notices…

… and nobody cares.

That’s the purest part of the fantasy.

He’s not just fantasising about suicide, he’s not just fantasising about dying, he’s fantasising about in the context of it then not causing anyone else distress. It doesn’t feel like Joe is hoping for a death that even then, nobody cares about, it feels like the thing that keeps Joe on this side of dying is that he doesn’t want to cause harm or distress in the doing. Joe doesn’t want to exist, and the fantasy he indulges with the knife and the bags is what if it was convenient to just stop existing?

When he’s roused – he’s still got his head on the table. He’s playing at being dead. He’s got his head down, he’s enjoying that stillness, the fantasy of not being alive any more for that moment.