In my teenager years, I came to appreciate the block of TV shows I thought of as ‘good shows’ in the 7:30 to 8:30 bracket. This typically took the form of a pair of back-to-back sitcom episodes, or, as I got older and the options got better (and my bedtime crept back), an hour long dramedy TV series, often built around a single high-concept hook, or even taped from late-night TV. A lot of these shows were, to my mind, ‘American Shows’ (and therefore good shows), were typically high-concept shows with sci-fi ideas in them that could be executed on cheaply with a small special effects budget, and included things like Time Trax and Pointman and, strangely important in my mind, a series called Fortune Hunter. I liked to refer to Fortune Hunter as a sort of example of forgettable 90s TV ephemera, a low-budget story about a wannabe James Bond type who was relaying everything through super-technology contact lenses to a nerd in a chair who could instantly relay everything to him. I, at the time, thought that Fortune Hunter was a great reference to make, like Street Sharks, which would make people in the same age range as I go ‘oh, yeah, that show, I remember that, kinda.’

Turns out that this was a terrible idea because, at the time I did not know, that Fortune Hunter aired for all of one month in America and only played out the full run of its episodes here in Australia because we were a dumping ground for failed attempted TV series that relied on high-concept sci-fi ideas that could be executed on cheaply with a small special effects budget. But those shows had some common traits, like Time Trax with its decreasing list of villains to apprehend, or Pointman with the fantasy of a strange billionaire appearing out of nowhere to save ordinary people, or Fortune Hunter with its gimmick of a super-nerd teaming up with a terrifying badass super-spy to save the day for single individuals.

I bring up this meandering reference to 90s television because these different stories with their modest production budgets and mediocre executions through actors who never quite got the respect they deserved are presented their absolute apotheosis in the form of the 2011-2016 sci-fi action series Person Of Interest.

Person of Interest is a sci-fi crime drama series that started airing in 2011 and that should make it hilariously dated except it’s not because it’s about the idea of a mass surveillance state and predictive models of human behaviour which is kind of a thing we’re talking about a lot right now.

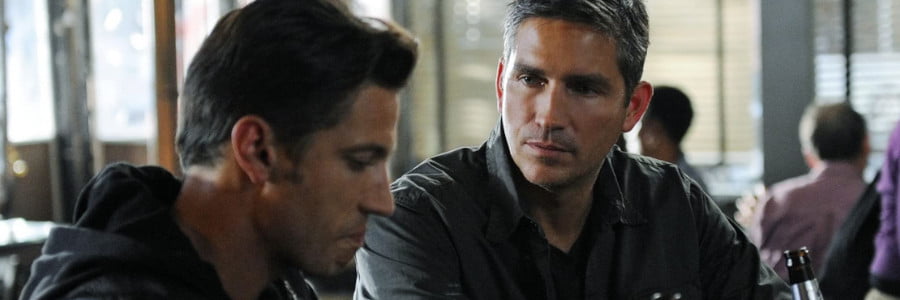

Your basic structure is that our heroes are composed for John Reese (probably not his name), a probably-CIA super-badass who goes around kicking ass against criminals that are typically, grossly outmatched against him, with a shockingly abrupt combat style (that films very, very quickly and easily) and a love for shooting people in the knee (you know to show how good he is with guns but also to not run the risk of killing people), teaming up with Harold Finch (probably not his name), an awkward gonky weirdo billionaire with supertech (that films very, very quickly and easily).

But really, it’s about The Machine.

The Machine is the core of this series in this season; it is the impetus for action and the establishing presence of the myth arc that the narrative runs on. In simplest terms, the Machine is a surveillance program that observes everything in the attempt to pre-emptively detect terror attacks made in the wake of 9/11 paranoia. This is a fun concept to work from because it’s a real thing that people tried to do, and it ran into all sorts of problems with how they got made, what they could try to do, and the limitations of publically available, legally actionable information. In this case, the conceit of the universe is that the device could be built and operated entirely discretely, and as long as nobody knows it exists and nobody knows what it could do, it’s just the same as a machine that makes anonymous tips to the authorities that happen to have a 100% reliable hit rate at detecting conspiracies for terror activities.

That’s super interesting, and they talk about ways this conceit is interesting, in ways that we aren’t grappling with perfectly right now. And since the conceit of the Machine is about taking care of terrorism, it generates a lot of false positives that don’t care about that primary goal. It finds crimes that are going to happen, deaths that are going to occur, and it then, if it can’t link them to mass casuality terrorism events (which we kind of get an indication disappeared in this universe because of the Machine), it discards them.

This is the story of our two protagonists as they try to address those numbers before they’re discarded. To answer a question ‘what would you do if there was something you could do?’ And the answer to that question is a lot of beating up baddies and cool car chases as the machine spits out weird cases, in no small part because the kinds of things the machine can detect are about isolating seemingly impossibly unrelated pieces of data. It’s a successful formula, of a crime-of-the-week hour-long series like your Blacklist and NCIS and CSI and BPA and IPL and you know I’m just making those up at this point.

It’s a cool hook for this season and I get the vibe that there’s a lot of storytelling space that’s being built out and not used. It’s shown in this first season that the story of these characters can do things like show up for a second appearance, that solutions and resolutions are being held back so that the story can do more with them later and that there is something of a conspiracy at work that doesn’t feel like it’s just using the same central thing as an excuse the whole way along, laying out track in an inward spiral.

Of course, the Machine is horrifying, and its appearances – the origin story for it, and its perspective – are both shot like a horror story and conceived of as like a horror story. There’s a long rolling background to the Machine that’s told in coldly lit, stark background stories that even when they’re trying to be told in ways that are funny or cute, are still all done as starkly and remotely as you might imagine archival footage of a tragedy happening.

Towards the end of the first season, Finch says he doesn’t regret making the machine, but he didn’t realise what it would cost him. The personal cost of the machine is manifold, and it means the whole machine is effectively running on human suffering and it’s all generating dreadful, painful guilt on every single intervening step, guilt that Finch and Reese spend their lives trying to dilute.

There’s no way for this kind of thing to exist, no way for something so powerful to work, without it being fundamentally, a structure for compromising. Compromising people, compromising security, compromising our ethical framework, our standards for legal strictures, and all of those things are necessary for something like The Machine to exist. What good is it doing? it’s saving a small number of people, every day, and it’s preventing international terrorism, but surely, is it the best way to do that? International terrorism happens because of causes and effects, it doesn’t run based on bad meals.

This first season feels like a prequel. It feels like a series that maybe wants to do something else, that there, like Fringe is going to be a conceptual escalation from season to season. It’s got some good names involved, and it ran for five years, so I’m genuinely wondering what I’m going to see as the series moves forward.

In the last episode of the first season, an antagonist, in response to Finch’s admission that he is okay with having made the machine, it’s in response to an antagonist asserting angrily to him that you have made god.

It’s an odd way to describe having constructed a kind of Laplace’s Demon.