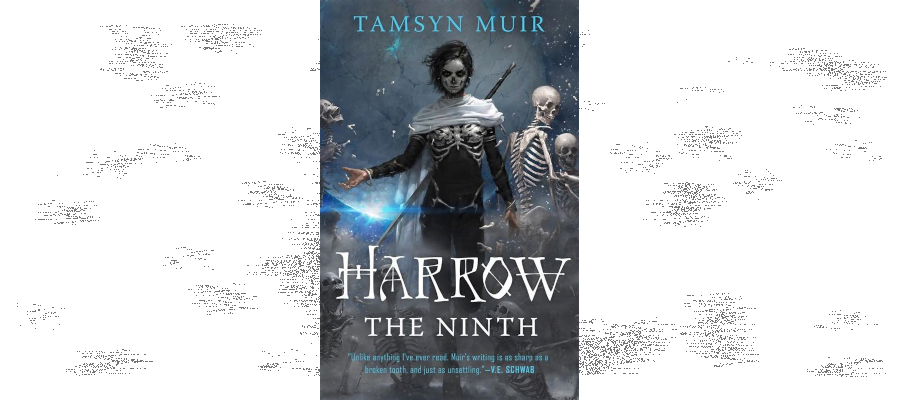

Harrow The Ninth is the second book in the four-and-a-half-book-so-far Locked Tomb trilogy by Tamsyn Muir, a New Zealand author, and to get the box blurb copy out of the way early, it’s as intricate as wristbones, multi-layered, wrought out of several kinds of deliberate excellence and also extremely bloody funny. It commands its venaculars and surgical terminology alongside one another to construct a narrative puzzlebox of regrets and rage and guilt and violence and queer shit and I loved it.

There are these healing moments of emotionally satisfying contact between people who you can maybe let your guard down and like because they don’t have to suck just because this situation sucks and maybe that’s the important thing, maybe it’s the friends we made along the way. Or maybe it’s really, really not. You’d have to get to the end of the book to start to find out what you think. I know what I think.

Now, it is a slight problem that Harrow The Ninth is a book that builds directly on the previous book, which is a book with a very distinct conclusion that leaves you wondering ‘okay, now how does this proceed,’ and Harrow The Ninth doesn’t actually give you easy answers. As a matter of simple necessity, then, and in order to discuss ideas in this book and why I love it, I am going to talk – even a bit obliquely – about the stuff in the book. Therefore, if you’re the kind of person who wants them, I put here, a SPOILER WARNING.

And you may think ‘oh come on, it’s a book with a twist, you can talk about stuff around that,’ and like kinda no not really, it’s way more complex than that, and even just telling you that is enough to make the wrong kind of mind leap at shadows thinking every single thing you deal with in the book is The Twist. Good news, though, because in this situation, oh natively paranoid, must-not-be-surprised, solve-it-first readers, you’re right!

Everything in this book is The Twist.

When I talk about the author of this work, understand I’m talking about this in the context of your Barthes-style critical engagement with the hypothetical author of a work, an individual expressed by the work that exists, not like I can sift through the word choice in this book to winnow away publication guidelines and editorial oversight and test reader input and anecdotes and tumblr jokes and Biblical references to try and pull out some narrow thread that reaches into Tamysn Muir’s head and interpolate something about her as a writer or a person. That’s not how this works, because if it did I could somehow supposedly divine the character of King David of Israel just because this quotes one of the Proverbs. No no no. Bear that in mind when you read the next bit, okay.

Holy shit this is an Australasian author.

And I don’t mean things like how Harrow’s story can be seen as the narrative we get, white as we are, about how being included in the system of Empire, get to benefit from this system of privilege as long as we are immediately useful but we all – all of us, both in group and out – we know that we’re not really part of it, and we are going to be thrown aside the second we stop being immediately useful or highlight how we’re different to the correct you.

I don’t even mean the way that Harrow’s entire perspective is broken into three pieces as she tries to construct a narrative of who she is, in the heart of a communal space that is also dying and cracking up because something terrible is happening. Don’t get me wrong, I definitely think this story is about how vast systems that affect huge numbers of people are in the name of benefitting a tiny number of dysfunctional shitheads, and how understanding them does require understanding that they don’t understand you, but that’s not what I’m getting at.

What I’m getting at is this is a book where, without any explanation or belief that an explanation is necessary, a narrator refers to the emperor losing his nana. And you may think ‘I know what that means’ but if you’re not from the area, no you don’t, it’s not his nanna, that’s a different thing, and the lovely audiobook reader made that mistake too.

This is a book that cares about words, though, and it cares in a way that’s awesomely clever. And as seems appropriate for this book, I want to pull over and talk about words for a moment.

First, clever. Often when I use the word ‘clever’ its a neutral term, an idea of how something can be done in an intricate way, a way that required a particular kind of good idea but that’s not the same thing as being the best way to do things. I know as a writer, I care a lot about being clever with wording and terminology because that’s something I can do, as someone who spends a year with the book that a reader who spends a few afternoons with it can’t necessarily. Clever can be a mousetrap but clever can be a clockwork.

Second, awesomely. It’s not a word I’m using here to indicate a generic positivity. It’s a word about being rendered, in a moment, bolted in spot in awe. A realisation that somehow I have been party to a magic trick, been fooled by someone who never lied to me, all because they were relying on me to imagine and anticipate a different lie.

The wordplay and subtle references and cleverness around terminology in the first book of The Locked Tomb danced across the whole narrative like constellations on a blue sheet of a sky. You could connect them all (hey, notice how all the characters are named after numbers?) and that definitely added depth to the work, but the story wasn’t about being clever, or inviting you to try and be clever. You were in a mind and body that approached everything with a headbutt. The close-in perspective of a mind that thinks about tits every third breath but nonetheless knows the word liquescent uses that deep vocabulary to tell you about the narrator. It also betrays a love of the words themselves, and a love of using them to control attention.

Harrow The Ninth feels like it took that same concept and instead asked, hey, what’s the most I can do with the least. How much weight can I use, how much power can I wield, with the least word possible? Harrow The Ninth is a book that completely transforms the very fundamental assumptions of what the story is doing at all based on the word ‘me.’ Not joking, not kidding. There’s a single point where the word ‘me’ appears on the page and at that point you have to stop and go back and reconsider everything before now and every single bit of comforting structure you assumed the book was doing that was also already pretty difficult to put together was wrong.

It’s like imagining you’re working on a completely white puzzle and you’ve got your four corners out of the box and you’re about halfway through these multiple different chunks that don’t connect to each other yet and then as you’re sifting through you find, taped to the inside of the box lid a fifth fucking corner piece.

I used to like talking about character voice in fiction with people, because it was a great way to show people the way work they loved did something they didn’t notice but once they noticed it, it was something of a revelation, and then over time, mass media eroded the practice and it actually became more common to see large groups of people who had a character voice, based on the work of the whole fiction. In Harrow The Ninth, this discipline, of being aware what one character would say and how they would say it and how they would think it, and how they would think of other people thinking it, is slowly unfolded like a dead rose, and if it wasn’t also engaging it would just feel like the most titanic flex.

There’s more, of course, because it’s not just doing something clever, every part of the machinery that locks the cleverness together is also individually engaging. What the hell is going on with Ortus? What do these flashbacks mean? Where is Ortus?

Why is Ortus’ sword so important and why isn’t Harrow even trying to work with it? Why is all this stuff in Canaan House not like it was in Ortus The Ninth? What does dying mean? What doesn’t dying mean? Is everyone here a shithead? Oh wait, no, is nobody here a shithead? How much of a huge smile did the author had when they made a None Grief, Oof Ow My Bones, I’m Dad, or There Goes Gravity joke? How universal an experience is it to hold onto love letters from someone you haven’t spoken to in a year that this book made me personally feel very small? Where the hell is Ortus?! And why aren’t the other characters asking ‘where’s Ortus?’

I’m obviously signed on to read the rest of the series and probably whatever else Muir makes at this point because it turns out that in addition to making stories that are very good and very impressive, they’re also about things I like to read about and have a willingness to be violent and funny and horny and smart in ways that I normally feel alienate me from other books. I know I’m meaner than stories want me to be, I know I can find a lot of fantasy novels about how religion is only bad when it’s bad, and empires can be okay, sometimes, actually, and maybe I’m just a bit much for the whole landscape of storytelling.

But not here.

Y’know what, I think at this point I have to accept that I’m absolutely just going to be one of those people who are Very About this franchise and consign myself to that fate. Don’t worry, I don’t expect to cosplay anything in it.

And now, here are some glib alternate titles I proposed to friends as I was reading it:

- Isn’t Dumbledore An Arsehole

- Gideon Navi

- How Harrowhark Was Always Right, Actually

- Old People Are Evil

- Wives Out

- Symbolism 301 As A Vomiting Goth

- Big Evil Clown Energy

- Girlboss Gaslight Girlboss

- Wight By The River

Ripper of a book. Absolutely choice.