Some of you out there are currently feeling bad about Bridget Guiltygear, about how a character you really liked the way it was now feels unavailable to you, and it’s in the very fraught, very distressing conversational space of Transgender Issues. You’re probably feeling in a way about it and you want someone to talk about it… and there’s nobody to talk to about it, because the conversational space is, as said, distressing.

Basically, if you’re someone who’s feeling a way about Bridget being a trans girl now, but you can recognise you’re feeling sad about you and not mad about the way other people are feeling, I’d like to talk to you. And I’d like to talk to you and offer you advice and guidance from a cohort that you might imagine is kind of your opposite: the trans Harry Potter fan.

Content Warning: I’m going to talk about Bridget a lot, and I’m going to talk about Harry Potter, and I’m going to do so with what I hope will be seen as compassion for people engaging with media. I’m obviously not endorsing or encouraging transphobia. I’m doing this as a good faith engagement with something complicated to talk about, and none of what I should say should be treated as any reason to get mad at people who are expressing their feelings.

First up, some language. We’re going to be talking about a character and it’s very important to recognise that characters are not people. They are made up constructs of a fictional reality that only exists as sustained by people invoking them. The big reason to do this, to nail down the idea that this is a fictional character is because there are ways to discuss a character that are absolutely inappropriate to discuss people. While characters are meant to represent people, they are definitely not the same thing.

As an example, when a trans person makes a declaration about their gender and pronouns, it’s simply a matter of politeness to refer to that person by their current gender and pronouns, because that is that person and you owe people a good faith recognition of their gender.

We’re going to talk about ‘good faith’ for a bit here, too. Basically, when I say ‘good faith’ I mean that I’m going to be looking at positions as if those positions are wholeheartedly and only the position in question. I know there are a lot of people who have opinions and want to argue about these ideas who are, ultimately, using the conversation around Bridget and femboys as a more socially-acceptable way to attack the representation of trans people, or even the positive reactions of trans people, and every one of those people can piss up a rope.

And oh boy, this had some discourse around it, and very silly discourse indeed. There was a very loud corncob who faked up an internal letter from the company to claim that they were all in fact, 100% on board with Bridget not really being a trans girl, but instead they were being bullied or ignored by other sources.

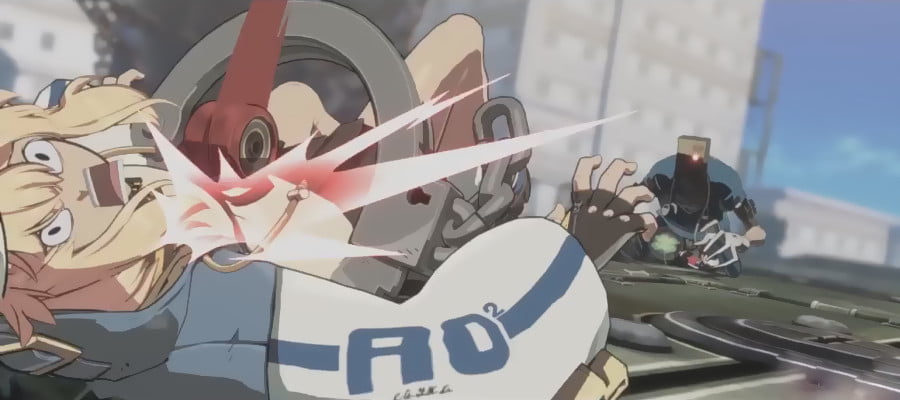

This is not a heavy lift, in the text. Let’s have a quick look at the first scene that the ‘Bridget is not a trans girl’ crowd like to point out:

Oh okay, so that seems nice and clear, Bridget, looking pensive and sad and down, with the text ‘I’m… I’m a boy.’ And then, this is the kind of thing that, when you remove it from context, if you want to, you can kind of claim is proof of ‘ambiguity’ in the storyline.

And that kind of claim is the kind of thing that relies on that lack of good faith. Because the scene above, yes, is taken from Bridget’s plotline, where Goldlewis starts out by addressing her in the feminine, and she clarifies but then, when she clarifies, it’s pensive, and she picks her words carefully about it.

Also, at the end of her plotline, Bridget has this exchange at the end of a conversation with Ky and Goldlewis about committing to changes and being willing to live freely:

Basically, this is ambiguous if you do not have object permanence or the idea of narrative progressing from one point to another. And that’s where this conversation of good faith has to circle around and clarify, because… the only way this is ambiguous is if you want it to be ambiguous, and if you think it’s ambiguous or hear it’s ambiguous and then argue for it to be ambiguous, then odds are good, you want it to be ambiguous, then didn’t look into the source material.

There’s ‘trust in a good faith position’ and then there’s ‘ignoring the source material,’ and pretending that Bridget is not a clearly declared girl in the text in front of you requires you to ignore source material. Which, you know, that is also fine! You can absolutely ignore source material when you make your own fan experiences; but again, that’s a step away from good faith interpretation, because we weren’t talking about fan experiences.

When discussing the canon text of the game Guilty Gear Strive there is a very clear textual statement that Bridget is a girl.

Therefore, a good faith discussion about this is not about a textual examination of whether or not Bridget is or is not a girl – the text stays she is. This examination instead wants to be about the much stickier, and much more challenging space of considering what Bridget being a girl makes you feel, and how to struggle with those feelings in a way that’s respectful and helpful. And to those end, I think I’m largely going to be talking to other guys.

First things first, step yourself through that set of explanations; are you defensively trying to argue that Guilty Gear Strive doesn’t include the passages described above? Are you trying to argue that that text doesn’t really mean that? That right there is negotiating with the text, which you only need to do if the text doesn’t demonstrate what you want it to. First things first: Accept that it’s canon in Guilty Gear Strive in ways that most people will talk about it, that Bridget the character is a trans girl. Attempting to pretend that she’s not, not really, or that in particular contexts, or it’s ambiguous, is something that, at the very least, looks bad to people who have no reason to know you or know your motivations.

It’s really common for trans people, the real ones, the non-fictional ones, to have their identities attacked and erased passively. Even in simple ways, if you’ve ever seen phrases like ‘who claims to be transgender’ or ‘so called’ or even ‘x, (birth name y),’ when used in common conversation, are ways that you can treat someone else’s declared gender as if it’s somehow something being negotiated about. It says ‘look, I know you say this about you, but I’m not sure you’re right,’ and that’s rude. At the very least, it’s rude.

Accept that the text is the way it is.

I’m assuming for you, the thing you liked was something Bridget represented. Let’s for the benefit of the doubt here, call it ‘femboy representation.’ That’s definitely a thing that we can talk about; the earlier identity of Bridget, as a (complicated) masc-represented character, did create a space for people to look at a boy, wearing an outfit that reads to you as ‘feminine’ and ‘cute’ and realise that was a thing you liked, and responded to, and wanted to see in the world. I know more than a few femboys who got their start thanks to characters like Bridget.

And in that case: Yeah! Especially for a character who is a long term part of your personal relationship with your gender and how you present it to the world around you, it’s a big deal when something about that character changes in a way that leaves you feeling like you’re not allowed to connect to that character any more. After all, if I, a cis guy, wore a Bridget Hoodie to a convention, there is a body of people who might (very well-naturedly!) interpret that as a cosplay, despite all the other ways I wouldn’t be trying to look like her, and might try to encourage me with what they perceive me as doing.

What’s more, if you were to try and represent a character as looking ‘like Bridget’, because Bridget is a trans woman, you might find that people react to the characters’ looking like Bridget as a signifier that that character is a trans woman.

Thing with this is… while yes, this is absolutely a concern that can happen, especially in playful spaces where you’re trying to have a fun time on the internet, it’s first of all, very very small potatoes (‘someone who never met them misgendered my OC’) and also, a useful example for how underrepresented trans women in media are. Oh there are trans women, but consider how in this case, one single character being a trans woman is seen as having an outsized influence.

There are a lot of fem boys in anime and manga. Like, so much so that they can be divided up into smaller subgroups. You could make a reasonably sized booru board that excluded every femboy who didn’t wear a tophat. The boundaries and forms of femboy presentation are also not aggressively policed and politicised; some people consider Rin Matsuoka a femboy, some people consider him far too muscular. Some people consider a femboy a fashion sense, some consider it a phenotype. The point is, femboy is a really varied type, and it can be explored and expressed in a lot of different ways, in canon media representations.

Bridget being a trans girl is definitely a change for those spaces. For a very long time, Bridget has been held up as an example of a wholesome femboy in a complicated story space where things get really weird. This change might have been intended originally, but earlier versions of the text didn’t make it clear, so once, it was ambiguous, and there was a generally settled common interpretation that Bridget was a femboy.

What’s more, none of this is trying to argue you out of how you feel. You’re allowed to have preferences and, again, this is about handling those feelings in a respectful way. That means not making other people responsible for your feelings, for a start. You liked Bridget more before when she wasn’t a girl. That’s okay. You, complaining to people who are happy about Bridget being a girl, that’s more in the realm of making your unhappiness their problem. And having the ability to recognise our own preferences is a really important thing for expressing ourselves when we talk about media.

There’s an impetus to make media consumption and its conversations about morality and intelligence. I read more books, I have a better framework, I have incorporated more layers, I’ve found the more important fine detail, all that stuff, which is perfectly good in academic deep readings that are about people poring over long form examinations for years. It isn’t at all helpful in conversation with people about the media they’re actually consuming. Telling someone you think their favourite thing sucks because it’s not Marxist enough or it’s too Marxist isn’t really engaging with the media in terms of how they relate to it, either (I mean, unless they’re doing Marxist analysese and you want to engage with those).

What people do is express their feelings. You can very seriously, accept and appreciate the joy of other people, and accept and recognise your own sadness, without those things being in competition. I know it can feel like there’s some control over these things, right? Like if they hadn’t done that with Bridget, the status quo would have persisted and you’d have things the way they were. Right? But your opinions, your preferences, aren’t going to change the things that ArcSystemWorx do. This happened, like a storm or the tides, and what you’d rather have happened doesn’t change what did.

The thing is, there’s an existing community out there who are there, and in many cases, very willing to talk to you about these kinds of things, and their feelings about them, who might be able to come at it from a different position to you, who might be able to help you grapple with this change.

I want you to look to the example of queer Hogwarts fans.

Now, in a big, broad, economical way, I can say ‘hey, don’t buy anything to do with Harry Potter. It pays money to a big dumb shithead who will use that money to hurt people.’ That’s a nice, easy thing for me to say. But I also wasn’t going to partake in that purchase in the first place. It would make no difference for me.

There are other fans, however.

Fans who are currently, in some ways, stifled by the discourse. There are Harry Potter fans who got their start creating in that space; who made friends in that space, who discovered things about themselves in that space. Specifically, the ones who discovered things about themselves in that space.

There are a body of trans fans of Harry Potter who are right now, stuck between very real feelings and the unpleasant realities of what that fandom enables. And for them, it’s not a simple path of ‘drop it.’ Some are going to refit their love. Some have taken to try and reclaim it, and some have struggled with this missing piece of themselves that they now, have to let go of but don’t want to. It can make people defensive and it can make them sad, and it can make it so that there’s this old love, and old shame, bound together, as reality moves on around it.

These problems are not commensurate in scale, by the way; a billionaire trying to change laws in a country based on how she thinks your genitals are icky is absolutely more of a present problem than people on the internet correcting you when you gender your OC version of Bridget. But the same fandom structures are there; something changed, something made this thing I liked feel different, and now I have to navigate how to handle this feeling responsibly, in a way that doesn’t hurt people or make life difficult for the people around me.

These are people navigating this space, and understanding one another in it. And they can, at the very least, talk to you about ways to handle this in a way that might help you understand the situation of trans people a bit better than if you just see them as somehow ‘taking’ something from you that they absolutely didn’t.

Bridget is a character I really like. I liked her before, and I like her now. For me, it was easy enough; I wasn’t projecting specific wants or preferences on the character like that, and she looks cool as hell and it’s not like I play the game. It doesn’t impact me a lot to say ‘hey, Bridget’s a girl now? Sick.’ For a lot of players, that’s not going to matter too much either: Lots of people who like Bridget do so because she’s a cool character who does cool things.

But if you were one of the few people who really liked Bridget in one particular way, and that way spoke to you and helped you make sense of things, it’s okay to not be happy with this change. It’s okay for you to think this change doesn’t make sense for you.

And it’s even better if Bridget lets you look at these feelings about yourself, things that you are certain of, things you do want to be a particular way, and that differ from where she’s gone on her journey. That’s cool. You wouldn’t want to miss out on the opportunities to live your life the way you wanted to, right?

Bridget wouldn’t want you to.