Back before you, satistically, were born, there was this thing called The Nineteen Hundred and Eighties. These are defined by nobody my age properly remembering them and attributing all sorts of things to them that didn’t necessarily exist. But also in that space, there were things like dating TV game shows, which took off in the 1970s and were petering out by the 80s.

Oh okay, so a dating TV game show is a TV game show where the premise is one of the prizes is a really cool date, and you win it by picking one of the potential dates and going out together.

Oh, so a TV game show is a type of game where the game is played primarily on TV, for an audience and—

Oh okay, so a TV is like a really big phone that only could receive streams from five people—

Anyway, the board game Dream Crush.

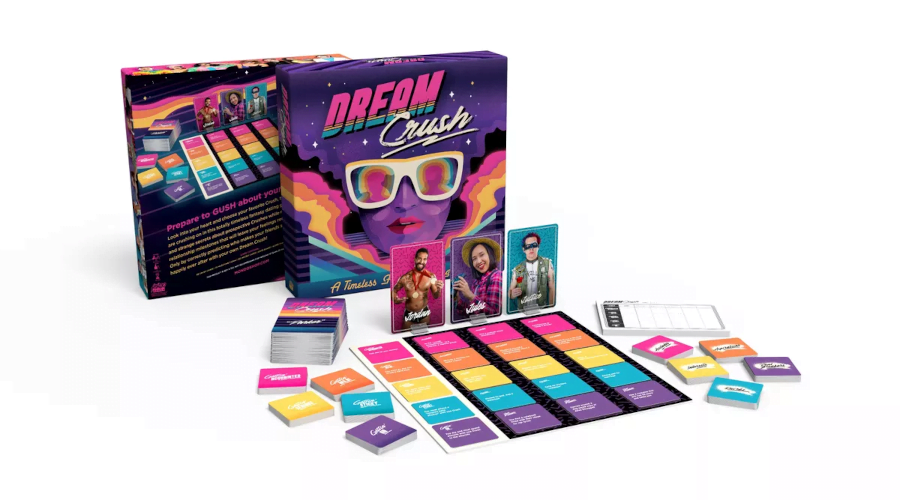

Dream Crush is, in its purest sense, a social deduction game. Players are presented with arbitarily similar options, and then every other player tries to guess what your choice would be amongst those options and for why. Players check these, scoring points based on if they correctly guessed what you would guess, then add another arbitary difference to the options, and repeat the process. The winner is the person with the most points, which really doesn’t matter. This isn’t a game with a powerful agonic edge – it’s honestly close to a combination of alea and mimicry instead, if you want that kind of reference.

But that anodyne description of the gameplay loop isn’t what it feels like what you’re doing. What you’re doing is meeting a collection of possible dateable people, and determining if you’d date them based on information that gets revealed about them in stages. This information is, typically speaking in this game, contentious but not direly negative; you’re not going to see a card that says, say ‘is a racist,’ but you might see a card that says ‘calls strangers sir and ma’am.’

The funny part of the game, and make no mistake, this is a game about making funny things happen, comes when you listen to people make assumptions about what would appeal to you, and how much these things matter to you.

What Dream Crush offers in this space that sets it apart from a lot of other voting games — well, the voting game that everyone knows in this space, really, which is Cards Against Humanity.

Like, you do know that right? Systemically speaking, Dream Crush and Cards Against Humanity are the same thing. They’re language roulettes, and you vote on who has the best combination of ball and slot. I have a special kind of low-key resentment about the way that Cards Against Humanity works, not because the engine works badly but because it’s taught a generation of players that this is how modern games work, that they’re all just voting games.

I see a lot of voting games in the indie space, games that more or less are trying to make a similar kind of product to Cards Against Humanity when they’re not just straight up making more of Cards Against Humanity. This is in part because they aren’t well-versed in alternatives, but it’s also because the core engine of that game is pretty strong in a particular kind of way. See, with Cards Against Humanity, the incentive system for the game is just screwed: You’re not actually incentivised to play the game well and care about who wins. What you’re trying to do is determine who played what and how to push points away from the player in the lead. Now, nobody does that, because it’s too hard, but when the cards are revealed and you can determine who reacts and how, it’s entirely possible to determine based on people’s reactions who is or isn’t playing a particular card.

The incentive system of that game, if you care about winning is a game of social reads in that voting period. Now, this never comes up because people who play Cards Against Humanity are focused instead on the ‘ridiculous’ outcomes of their ‘joke’ cards.

In Dream Crush you’re not trying to construct a joke and punchline combination. The game is producing potential date options, players are discussing what they think about those options, and then people are making a choice from this selection and other players try to predict what you did. You don’t score points based on what you chose, you score points based on what you can determine of other people’s choices – and that means that you need information.

The game presents you with ways to get information – like, asking questions – but you can’t actually coerce it out of anyone. There’s no ‘look at a player’s hand’ thing here. The game is very much a game about communication. Where many other voting games want to obscure people’s choices during the choosing, Dream Crush uses its formula to instead induce players to talk.

The game rules do specify you need to be true to your heart and that’s a good push towards a sort of good faith engagement with the game’s fiction. It’s not actually that important, like you can’t prove someone’s heart or preferences, but even if you try to play to the most mechanistically challenging play pattern, you don’t score any more points by messing with people’s abilities to guess you. You still need to be able to work out what other people are choosing, in order to play the game and that means that even if you don’t want to engage, you still need other people to talk!

It’s not like Dream Crush is going to work for everyone. It still builds itself around the idea of going on dates and building relationships with people which isn’t universal experiences go. For anyone who finds it a no-go it’s a hard no-go, and it sucks to get completely walled by the fun goofy game that everyone else is able to enjoy. Plus, there are some people who wouldn’t be comfortable picking certain kinds of partner, which can be based on how they physically read the cards. Don’t push it with this otherwise pretty novel game.

Still there is one final detail: Character names are deliberately chosen to be gender ambiguous, and for a large cast of them, that means that you’re dealing with a body of weirdoes who have hobbies like sword collection and muppetry and use flip phones and have gender ambiguous names. What I’m saying is that there’s a very real Nonbinary Polycule Interaction simulator buried here.