If you search my blog for this game, you will find mentions of it. You will find references to it, and discussions of it in the context of making games, redesigning mechanics, and even mentioned in an anime where they play Cockroach Poker. I own a copy of this game, and yet somehow I’ve never presented a Game Pile article on its own about this game.

It feels like I should have gotten to this before now, but describing Cockroach Poker almost feels like I’m diagramming a fractal. Come on, then, learn about some of the smallest and tightest Units Of Game you can get.

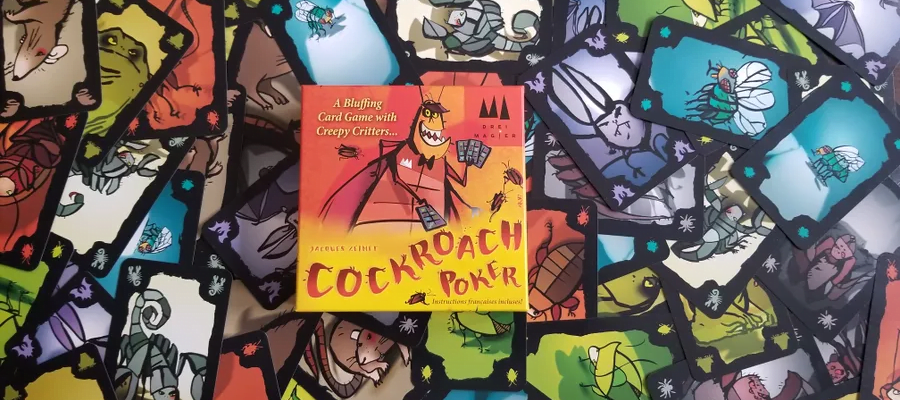

Cockroach Poker is one of the simplest games to construct you can find; almost comparable with DIY-project games like Skull where you can play it with a handful of beer coasters. There are eight suits of cards, and there are eight cards of each. They have a unified card back which shows you the eight symbols, representing the eight sets. That’s it, that’s how pure Cockroach Poker is. You don’t have to shuffle the cards up in a particular way, you don’t have to stack or prep the deck, you don’t even need a place for the deck to rest while people play. You shuffle, you deal to each player all the cards, and then you can play. As an interface, there’s almost nothing in Cockroach Poker but the purest, simplest execution of playing the game. It doesn’t even have or need text on any game objects!

There’s a fiction – all games have that – but if you asked what ‘the story’ of this game is, I don’t imagine people would parse that. It’s like Poker, a game where people wouldn’t conventionally consider there to be a fiction at all.

I like games like this, I like making games like this.

Cockroach Poker is built around a play loop so small and so tight that ‘how to play’ explainers often have to pad things out to manage to get long enough to include ads. You can learn how to play Cockroach Poker in about two minutes, and with the setup already out of the way, here’s the play loop.

- A player takes a card and offers it to another player face-down, telling them that it’s a card of one of the eight sets.

- That player can choose to agree or disagree with that player, flipping the card over.

- If they’re right, the player who sent the card gets the card in front of them face-up.

- If they’re wrong, the player who guessed wrong gets the card in front of them face up.

- If the player doesn’t want to try and agree or disagree, they can pass the card on.

- If you pass it, you look at the card (without showing other people), then offer it face-down to another player who hasn’t dealt with this card this round.

The play loop resets at that point! It’s so simple and so pure, and the way you win the game, is by not being the one loser. The first player who gets four of any suit is the loser, and that’s it.

Now, with these rules in place, you’ll see a fairly predictable pattern. A player will look at the cards in their hand, uncertainly, and hand over a card face-down and then say, with the card face down on the table in front of them, “This is ah, uhhhhh-” as they look at the back of the card to work out what they’re about to say.

And that’s beautiful, because then any player who knows the game should watch that moment and immediately, automatically, know whether or not they’re lying. But the thing is, if that player is handing it to the more expert player, the more expert player should probably just pass it on, agree with what they said, and sit back to watch who reacts to that and how. Because you’re passing on what you were told, suddenly the new player you’re passing it to isn’t checking whether they believe you, they’re checking whether they believe the first player, but they’ve also seen you pass the card on, and what’s the easiest thing for them to do then?

Pass it on again.

Cockroach Poker throws this tension of lies into the play space, and people don’t want to know or be sure about what happens or anything like that, and then when the tension snaps shut, and people suddenly and abruptly win or lose and a card finally finds its way into a player’s possession and they’re left wondering: oh no, now what.

Now you do it again.

And you’re fine. You only have one card from one suit.

The tension relaxes, but now it’s someone’s turn to offer another card and that cycle starts again. People learn about the game in an individual sequence of plays, and the playing of it involves learning about not just about the games’ rules but about the people around the table with them. It becomes a game where you’re trying to learn about predictable behaviour of your opponents, while they’re trying to learn about how to find ways to be unpredictable. Strategy emerges as people start to exploit weaknesses. If you have two rats, and I want a safe turn, I can almost guarantee you’re going to pass if the first thing I do is offer you a rat, because you don’t want to hit three rats and be at risk of a knockout if you’re at the end of a chain of passes.

But also players learn at different rates, and you can never be certain you have a player on lock! You might think you know a player’s tells perfectly, but how confident are you on that? How much do you think you can sustain that?

This is a game where you want to be the last person to make a mistake.

My copy of this game does not live in my house. It lives at the university, where I get to watch students play it. ‘Cos when I play it with people who have to see me a second time, it gets real anxiety inducing real, real quick. I understand that! It’s a game that’s almost purified to the point of toxicity.

Sixty four cards, eight suits, tiny play loop.

Go.