We Should Talk is a 2020 conversational visual novel produced by Insatiable Cycle and released by Whitehorn games. The scenario is small, and simple, and intimate: You’re at a bar, your partner is at home, and you chat with some people face-to-face, and your partner via your phone, and… that’s it. You chat, then the story culminates in a decision point that starts with someone saying we should talk.

The game’s available on a bunch of platforms, particularly Steam and Itch, and if you’re in the right mood, right now, for a game that’s interesting, more than a game that tells a necessarily compelling story, or has specifically challenging gameplay, you should definitely consider checking it out. It’s been in a few bundles, you might even have it!

Now, if you want me to talk more about the game and how I feel about it, well, that’s spoiler territory, so let’s look at it after the fold.

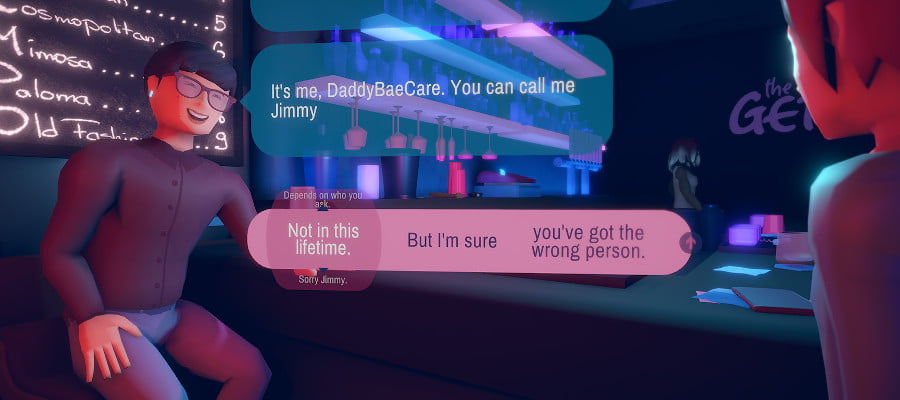

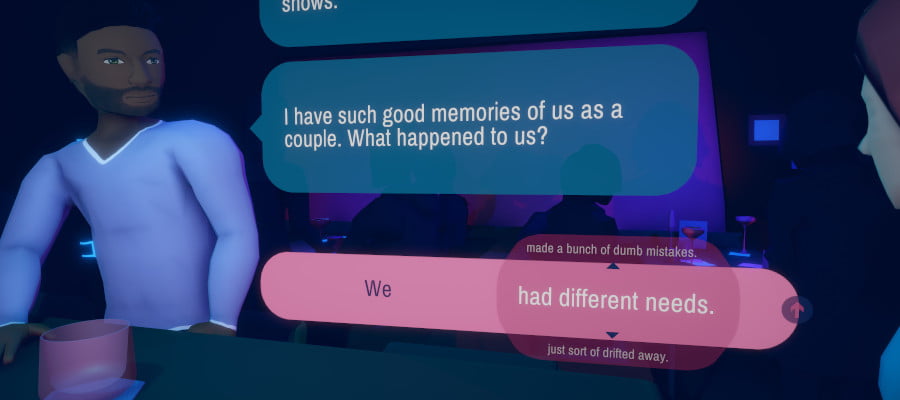

The big draw of this game, and part of why it’s so ‘short’ when you actually recount the number of game choices you make, is that this is a game that wants to examine one specific point of the game’s systems, and that’s this conversation system. When you’re prompted to speak, the game gives you a text box, where statements are made up of a variety of different clauses, allowing you to tailor phrases out of pieces from exchange to exchange. This is a design interface that seems to suggest a lot of very precise fine-tuning, where every possible phrase is considered at least a little bit different to all its possible alternate permutations.

If that’s the case, then that kind of fractal spreading and careful flag management presents a game that’s packed in fairly tight in its small amount of time. The actual system is interesting to consider, and since the game is mostly about engaging with that system, it doesn’t really do anything that doesn’t fit into that system. This means that the game presents you with that conversation system, an NPC explains it diegetically, and from there, the whole game is about using that system.

Any backstory or surrounding details about your character are then told to you from implication. Characters mention seeing you in the past or dealing with something they know you’re interested in, and in so doing, the game uses its interface to do what it wants to do (encourage you to have conversations) while doing something to tell its story. It’s clever!

Now, that isn’t to say I responded to it really well, though. It feels like a game where authenticity is a big part of how it engages the audience, where these are very real-feeling conversations of real-feeling time hanging out at a real-feeling bar as a real-feeling person and I could sit here and pontificate about how well it captures that feeling, an ephemeral je nes sais quail but I’d be lying. I don’t know what it’s like to hang out at a bar. I don’t know what it’s like to get hit on at a bar. I don’t know what it’s like to meet up with an ex where there’s a little bit of a flame going on there and you’re thinking about it and so’s they, I simply do not know.

I’m not a bar guy! When I got the message from my partner at the start of the game about how she made food and wanted me there and that we lived together, I immediately wondered if I was supposed to just put the drink down and go home, because that seems the most obvious thing to do to me. I don’t like bars. I don’t get hit on. I don’t have a chequered past of complicated love interests. It’s all alien to me, and that means that for all that this seems like it’s authentic to someone else’s experience, it just made me feel awkward and, lacking no other word for it, cringe.

This is more important than you may think: Games use their fiction to encourage our ability to engage with them. If you drop me in a dungeon with a gun and some Nazis, I’m going to assume this game wants me to shoot Nazis with a gun rather than conduct seances to refine sweetened popcorn recipes. The unfamiliarity with this experience for me was weirdly uncanny, meaning in my first playthrough, I found myself stumbling around what choices to make, because I honestly didn’t know what the game wanted, or what it wanted me to want. Really, I thought it sounded like a stupid place to be, since my partner had just told me she was having a bad day and had food, but maybe I misunderstood the way the bar mattered to this character?

The result was a few playthroughs where I kind of just picked the most basic default answers I could, only changing things to avoid open and flagrant assholery. It’s funny, a lot of my involvement with this game could be reduced to pressing okay on default options, but I still felt like I played it. I also didn’t feel a want to explore, because all that exploration was in aid of avoiding my partner, who I have no reason, in the play throughs I did, to think of as anything but someone I care for who made me noodles.

It’s not like it isn’t interesting to engage with. Sitting and considering the different potential ramifications of the text system, the things you could do with it, was very interesting. I had no interest in doing it, I didn’t want to press okay on any of the alternate options, but that’s because the system was interesting to me and the fiction wasn’t. In the half-real world of videogames, the real rules caught my attention while the fictional world drifted right past me.

Fundamentally we’re talking about a design that requires you to work out what is defined and not told, and what’s not told and not defined. The result is that you’re groping around to find the shape of negative space, like a blind person investigating an elephant. It’s a mystery, of sorts, but rather than a murder or a political intrigue, you’re trying to divine the secret of why you’re a crappy girlfriend.

Interesting! Relationships-focused! Engaging! Praise upon praise for a game I didn’t like much!