I need a term for something, so let’s invent it.

The term is going to use some language to represent a thing, and that language is going to need some history. That history is going to need some context, and some caveats, some asterisks, etcetera. Also, some of what I’m going to talk about can be seen as a polite disagreement with Ian Danskin’s videos on The Death of Guybrush Threepwood, essays from 2015.

Way to strike while the iron is gone.

What I want to talk about today is a particular family of games, or what we might know as a genre of games. Genre’s a beast of a thing to nail down, and I’ve said so in the past – it’s a well-established canard that ‘JRPG’ and ‘FPS’ are both genres even though one is defined by a country of origin and the other by a camera angle. Still, genre’s the term we have, so genre is what we must use, I guess, I’m only trying to invent one thing at a time here.

There is a type of game, and we don’t have a good term for it, right now, or at least, I haven’t seen one. I can’t tell you what I mean by naming the term we use for it, because if I do that you’ll immediately think of those games and only those games that are closest to it, and we want to keep our minds open here. We want to maximise the coverage of this terminology.

Instead, I’m also going to mention a bunch of games, by name, and I want you to think about how they’re all related.

Okay.

Full Throttle

Heavy Rain

Flight of the Amazon Queen

Myst

Beneath a Steel Sky

Six Days a Sacrifice

Broken Age

The Walking Dead

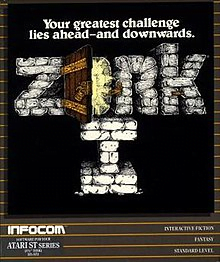

Zork

Grim Fandango

Blade Runner

Space Quest 3

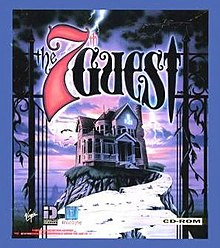

The 7th Guest

Curse of Monkey Island

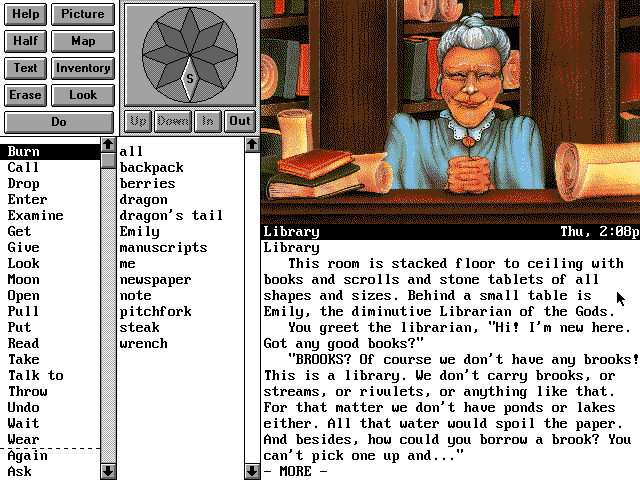

Can you see it? The thread of these games all connected one to another? Conventionally speaking, when we talk about these games, we often focus on one period of them – lords knows a lot of ink has been spilled for the period of 80s Sierra through 90s Lucasarts. When we do that, we often use the term ‘point and click adventure.’ That particular description seems it should include Myst, or Phantasmagoria – you do after all point and click in those, yet they’re often left out of the conversation. Twine games, like Climb by Sav Ferguson only can be engaged with through pointing and clicking, but most people wouldn’t consider them the same kind of game. Point-and-click excludes all the Space Quests and Kings Quests that weren’t being made with that interface, even though I feel they’re all very definitely games of the same type.

None of these games has useful traits in common with all these games. We can only point to the way they all, together, cast common shadows, occluding a sort of general space.

For now, I’d like to use a term to describe what I’m talking about, and what those traits mean. I’m going to call these games Narrative Adventures. A Narrative Adventure is a game that:

- Has a linear fiction with a beginning and an end that is treated as important

- Impedes the progress of that fiction narrative with puzzles

- Those puzzles are to be solved within the fiction

- The solutions to those puzzles are non-redundant

- Has no presumed default action to solve problems

Now, Narrative Adventure is in no ways a better term than point-and-click, not really. After all, Ocarina of Time has a narrative and it’s an adventure, so it’s not like the name couldn’t intuitively apply there. We want to avoid being too hung up on the perfection of the term, though: I want to avoid Point and Click adventure because I want to include games with text parsers and interactive fiction games like twine games and that one interface is too narrow. What I’m making here is an umbrella term.

Now, when we have the term, I can talk a bit more flexibly about Narrative Adventures, which is a genre bursting with games, good games, in constant evolution and explorations from their genesis all the way through to now. Which is strange because it’s accepted wisdom that they sort of all died out in the 90s, with the release of games like Gabriel Knight 3. The joke, which I’ve heard parroted (and I can understand parroting it, it’s a funny line) is that the point-and-click adventure game did not die, it commited suicide.

Ian Danskin forwarded in a discussion of this same idea that the games of this ilk passed away because the genre failed to innovate or evolve, comparing this to the history of the FPS. Now, there is actually some sinew to this idea: If you reach back to the dawn of the Narrative Adventure, the first ‘big name’ company in the business was Infocom, and we’re going to start here by talking about Zork. We’re going to start with Zork not because it was the first game, but because it’s as good a place to start as any. If you want a more in-depth examination of the genre’s history, I encourage you to check out Chapter 3 of Twisty Little Passages by Nick Montfort. All history is a summary, after all.

Infocom were the company that made Zork, along with quite a few other games; over the next eight years, they made something like twenty-eight games, which is a rate comparable to 3 games every single year. They were also making games for platforms that weren’t seen as having any games at all. Magazines of the day estimated seriously that an infocom game existed on probably half of all ‘non videogame’ platforms in use, and probably all of them if you included the pirated copies. During the period where videogames were defined by Nintendo and Sega, Infocom were making Narrative Adventures for a machine that most people thought of as used for accountancy.

Infocom wanted to make business software, and they weren’t really very interested in recruiting graphic designers. They outsourced their branding to a few other studios that did want to make some graphical games, but none of them were well-supported or caught on. Infocom did not want to evolve or change, and they ran out of ways to interest people in their work. With their passing, so passed the idea of the Text Adventure as a mainstream videogame.

Still, just because Infocom weren’t developing the genre doesn’t mean nobody was. At this point, Sierra had started distributing their games, games like Kings Quest and Space Quest and Leisure Suit Larry, Narrative Adventures with graphics, and an avatar you could position in the story space. Plenty of people were making Sierra-like games, including some really primitive point-and-click games (hi Delphine!), and even some experiments in borrowing from the Visual novel with first-person perspective games like Eric the Unready. God.

Look at this game.

This game was 1993.

This game came out the same year as Doom and Myst.

Anyway, Lucasarts brought along Maniac Mansion, and then we start to talk about point-and-click interfaces, and the Sierra games take on those traits. Then we get 3D, and we get games that care about that 3D, and we get some games that hold to and some that leave behind these traits and the conversation mostly becomes about what you can do when you’re spending Star Wars money. Then in the age of 3d adventures, there’s this period of collapse, sort of, and people tend to talk about Myst as something of an afterthought, because it didn’t fit neatly into the Lucasarts/Sierra discussion, even though it was happening at the same time.

Myst represented another innovation, in that it was one of the first games developed not so much with its unique gameplay interface but the sheer volume of stuff you could store on a CD-Rom. This amount was, for the time, mind-blowing. It couldn’t be retrieved off a CD quickly, but you could put dozens of megabytes of video in a CD-Rom game, and Myst did.

Trivia: If you go back and look at some of these old games they’re surprisingly small, sometimes only fifty meg or so, which is mostly because even if you put 600 megabytes of game content on a CD-Rom, you wouldn’t be able to pull it off the disc at any kind of speed. Fifty megabytes and six hundred megabytes were both just preposterously large amounts of space when you compared them to the two to four meg you had to work with on a floppy.

That lack of access speed led to compression tricks (hi, Command & Conquer, you’re giving us a hand, are you?) and that set of tricks led to the development of FMV games, like Under a Killing Moon, and, yes, Phantasmagoria. I’m reluctant, in the discussion of Narrative Adventure games to point to Night Trap as a game in this genre, but that’s a gut feeling. I don’t know the game very well at all.

The thing that’s often missed in all this is the compressed time frame of these games, and just how prolific some of these companies were. Between 1983 and 1990, before moving to point-and-click engines, Sierra released twenty one Narrative Adventure games; three Space Quest Games, four Kings Quest Games, two Police Quests, and two Quest for Glory games, along with a host of other one-shots or weirdo things like the Manhunter games. There were other games coming out at the same time – things like Thexder that were more conventional platformer games.

The reason Sierra could pump out these releases was that Sierra made an engine and then gave that engine to developers to make the games. Sierra could go wide and they made tools to enable going wide. Technology that one developer needed got implemented in other developers’ games later. When point-and-click adventure games became the thing, Sierra made the SCI engine and all their franchises moved into point-and-click games. That engine lasted them for the next twenty-eight Narrative Adventure games – which took three years. That is a ridiculous pace.

Part of what let Sierra do this though was the fungibility of their storage hardware. A 3.5 inch floppy in 1988, if you installed Police Quest on it and it didn’t sell, you could just wipe it and put another game on it. There was less risk in individual games not selling, so you were well served to make a big variety of games and hope some of them would hit a niche.

This is invisible ink of this ‘golden age’ of Narrative Adventures: The reason all these great games came out here was because heaps of all the games were being made and the risk for failure wasn’t very high.

Lucasarts had a similar engine innovation with the SCUMM system, which gave us their swell of games in a similarly short window of time. If you want an idea of just how far back this reached, one of the real concerns about playing games like Monkey Island was that your computer might not have a mouse, and needed to handle joystick compatibility to take its place. A joystick that could only be assumed to have two buttons. If you want to know more about how PCs handled joysticks, the summary from a friend of mine is ‘extremely poorly.’

Also, if you want to point to a big difference between Lucasarts and Sierra around this time, look not to graphics but to sound. Sierra games have some very noodly audio and forgettable midi riffs, but the iMuse system in early SCUMM games put music front and centre, and when it turns out you work in the same company as John Williams, there’s a lot of good musical skill you can draw on.

What we see as shifts in the gaming landscape are not games for games’ sakes, but are in fact changes in interface and infrastructure. Zork was 100% doable in terms of its computational requirements on a NES, but you’d absolutely need a keyboard to make the game enjoyable to play, and for a NES, a keyboard was a secondary peripheral. The point-and-click took over the PC Narrative Adventure space as the mouse became widespread. When the CD-ROM drive became commonplace, Myst rose, and along with that came games like 7th Guest. When you had the storage for voice acting, your needs changed for Narrative Adventures, and you could make whole puzzles around a dimension that you didn’t have before. This also introduced a host of accessibility problems as well.

This isn’t to sell any of these games short as just riders on their technology. There is however something to be said for being supported.

Typically speaking there’s a sharp jump in the discourse from around 1998 to 2013, when the Double Fine Kickstarter positioned itself as being a return of this game form. Now, this being April I feel allowed to be needlessly petty about this, but I was mad at the time and I’m still mad now: The Narrative Adventure, even the Lucasarts-style point-and-clicker, had not gone anywhere. It just wasn’t being made by the same types of people.

In the period between Grim Fandango and Double Fine Kickstarter, there was a lot of stuff made. Back in 2000, Yahtzee was releasing his earliest games which would lead in to the release of games like Five Days A Stranger. Dave Gilbert was making games like the Shivah, and the Blackwell series. The Myst-like was being explored in tiny spaces of the Escape Room flash game, with development teams of basically nobody. Those platforms and support for these ideas were indie gaming circles, free forums, and people who were following creative common-access tools like Adventure Game Studio, and audience platforms like Kongregate and Newgrounds. Again, it’s nice to be supported.

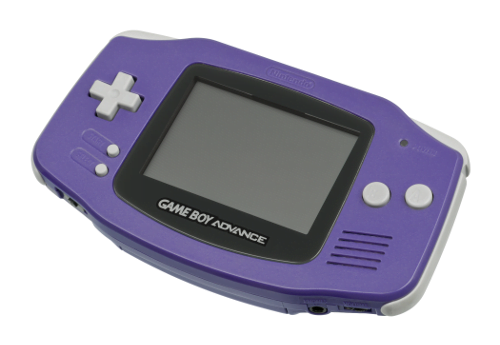

If interface and support are part of what shapes these games there’s a space for Narrative Adventures that happened between 2001 and 2012 which often goes completely unobserved and sometimes even unconsciously excluded from the conversation. The Gameboy Advance came out in 2001 with its most prominent Narrative Adventure game franchise being what we call in the west Ace Attorney. These games were originally made to work on the Gameboy Advance, with four buttons and a d-pad, and then later on the NDS, which had a touch pad to work with. The interface these games could use plays into how they’re designed, and how other games in the same genre work. Hotel Dusk is a Narrative Adventure game that asks you to hold your NDS like a book and has FPS-navigating sections throughout! That’s amazing, and it’s all through the different type of interface.

It wasn’t even like these were times of genuine famine for the Narrative Adventure in the triple-A space either, with games like Heavy Rain and LA Noire trying to bring in different mechanics to connect to the same basic push. You had Telltale games (RIP) releasing Narrative Adventurers since around 2005.

This isn’t a complete history, of course. There’s stuff I’m missing. I’m trying to give you a feel for the continuity between that time of a so-called ‘death’ because Lucasarts was busy cashing in Kyle Katarn’s cheques and Sierra was collapsing under its attempt to basically make Steam before anyone shopped on the internet.

With that in mind, that’s why I want to have this term. I don’t want to talk about ‘point and click adventures’ as if two companies over three ears basically own the entire creative space that both of them chose to vacate. I don’t think the Gone Home and Richard and Alice should be seen primarily in their relationship to the early 90s. I want to talk about all these games as if they are connected to and owe one another, and are all part of a great shared corpus of interesting ideas and ways to tell stories, through games, and engage you with their worlds. Some are RPGmaker games, some are point-and-clickers, some are first-person-explorers, but to me they’re all meaningfully Narrative Adventures.

And hey, maybe next week someone will prove to me this is a silly idea. But I need this term for later on, so, hey, bear with me.

4 Trackbacks