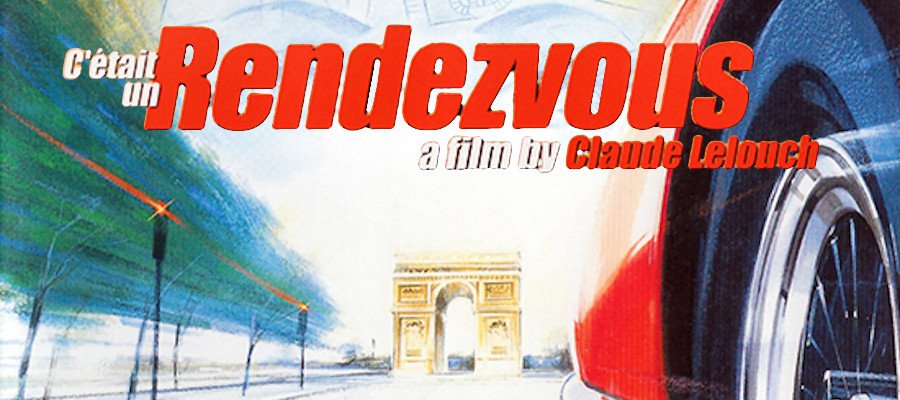

In 1976, Claude Lelouch, a french filmmaker, released a short video, about eight minutes long, which showed a single take of an anonymous driver driving ten kilometers through the center of Paris, at an average speed of 80 kilometers/50 miles per hour. You don’t see the car. You don’t hear talking. You don’t get any framing at all for the experience; you start in the car, as it leaves a tunnel, and then you have nothing to do but sit, like a passenger, as the car’s tires squeal, the engine revs, and the driver proceeds to break quite a few laws.

It is a real recording of a real excursion that really broke real laws: speed limits were ignored, eighteen red lights were violated and one-way streets were driven up the wrong way. While there’s no obvious danger to the public on the path, the fact that this was a real thing that was really done, there’s some inherent unpredictability about the things that could have happened, even at 5:30 in the morning in summer, where there’s not a lot of people going through the streets of Paris.

Now obviously, me being me, you might assume I’m pretty okay on some laws being ignored, and there’s definitely a case, though also, rich french dude who could afford a sports car getting away with violating a bunch of car laws isn’t exactly anarchist praxis as much as it is just what we expect. There’s not a lot of Being Gay in this Doing Crimes video. There’s also a potential angle you can take on this video about the way it’s a bit of a magic trick; we only see this version because this is the version where nothing went wrong, and we don’t know how many other versions of it happened, how many other versions of it could have happened, where things were a little different. We know there was a walkie-talkie and a spotter involved, even if it didn’t wind up being a factor, and regardless of the realities of how this video got made, as a text, you don’t get to know anything about that. With such a small, generic diegesis, you could dig into what it means, what the miniscule scrap of text really does explain.

I’m not going to do that, though.

I think this is a speedrun.

When I talked about Speedruns a few years ago, I used the reference to the idea of an etude; a form of composition that existed to not necessarily express some emotional or fictive space in the musical form, but instead to demonstrate and practice technical expertise in a particular element of the music’s construction. There are lots of etudes, which you may, if you hear them in part, think sound like ‘classical music’ in the general way of these things. But etudes are in many cases very much about developing and refining specific skills – there are etudes for specific fingers, practicing particular patterns and timing, all that stuff.

When I talk about media, one of the things I love to do is take older forms of media and connect them to newer ones. When I talk about videogames and recent board games, I do so by drawing a line through them to older games, games that reach back to the 15th century, because we have that information, and because, to me, it’s important to remember that our history is not a unique thing, sprung out of nowhere. We have always been connected to our pasts, and that connection is a long, extensive and complex thing.

The whole point of The Rendezvous is to show off how cool this thing is. It’s a demonstration of a technical skill that’s only capable of demonstration in this one very specific way. It also kind of has to be a real execution and done in this specific way, in a live fire environment, or the things that stop the presentation from being ‘real’ taint the demonstration of the skill. Of course at the same time, that demonstration of skill is absolutely nonsense because no, nobody needs to be able to race through the Paris inner city. It’s a skill executed on entirely to demonstrate that the skill can be executed on.

And of course, it’s also a bunch of crimes and it kind of sucks, because the guy doing it was still doing a thing that presented cars as prominent and all it takes is one pedestrian to make this story a different kind of very minor news story.

This connection to our past, and the importance of this practice as it relates to a past helps to connect us outwards. This was ‘how well can I do this, in a way that I can share it?’ and then you can draw a line from that to other forms of technical, speed-based executions. No wait, that’s too complicated to express, let’s simplify it, so, first up, Chopin invented the Etude, Claude LeLouch made the Rendezvous, then in let’s say 2016, Trevperson invented the Majora’s Mask speedrun, and from there, everything else has kind of happened. Okay, so with that nice simplified history, the point is, that this race, this execution of car-driving-goodness is not, in any way, improved by the involvement of pedestrians. It’s all got the vibe of a sneaky trick, getting away with something.

I’ve seen that too, though! In speedruns, some games resist tricks, sometimes you’ll find this experience where hey, does that work and the answer is not always. Sometimes you’ll get an experience that doesn’t quite work all the same ways every time, and you’re presented with all sorts of strategic needs around it. Does this kill the run? Does it fail early, and if it does, how does it fail early? Does it fail late, and if it fails late, is it failing with a restart? What if the game’s last decision has a 50/50% chance to completely break the run?

It’s a matter of how these things reset. Etudes, you can reset any time, and the question of what you’re practicing tells you where you jump in. A game, you can reset or use save states (for practice) or you can deliberately play your speedrun to create optimised experiences (like tool assisted speedruns).

And that’s pretty cool since it’s a lot better without the risk of, y’know, hitting a pedestrian.