DISCOURSE CONTAINMENT

Neon Genesis Evangelion is twenty-five years old. It is not a new series. It is not a series lacking in exposition or consideration or study. It is an important text but it is also vitally an old text. There is a degree to which the conversations around Evangelion are not just uninteresting, but are now completely tedious.

You might have seen it the first time, ever, this week. You might be planning on watching it. You might be wavering on whether or not you do. After all, it’s a Big Deal, why not?

There will be no meaningful spoilers for Evangelion. I’m barely going to talk about anything that’s in the show at all. But I am going to talk about this series and some of the reasons it matters, and the most important fact, that this series means a lot less than it matters.

DISCOURSE CONTAINMENT

First things first, Evangelion is a deeply personal thing for anime fans of the past thirty years, because whether you loved it or hated it, you almost certainly have a very clear opinion on it. One of the things you’ll find us old wardens of anime, the weathered veterans who still remember swapping altfics of Evangelion on forums and usenets knowing is Evangelion as a part of the landscape of which we have an opinion.

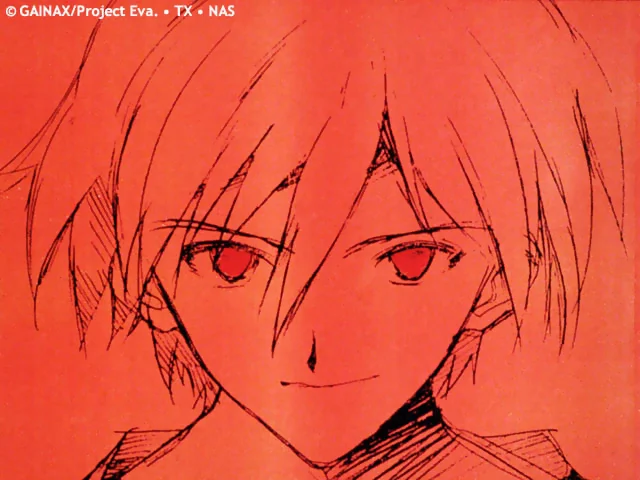

Let’s give you the critical details; Neon Genesis Evangelion is a 26-episode anime produced by Gainax, directorially credited to Hideako Anno, and screened for the first time on Japanese TV from 1995 to 1996. That’s your vital statistics, and none of it is meaningful or useful, because the odds are close to zero any of that information has anything to do with how you, an English language reader, came to experience Evangelion.

There are some points of history about it; some details of context; for example, Hideako Anno is a person who was in charge of the story of Evangelion, and he dealt on the one hand with his sister (a manga-ka) being hit by a truck and his own depression while he was working on the show, and Christian terrorist attack in Japan resulting in demands being made on the show to change, which was part of why things towards the end of the series get, let’s say ‘weird.’

Then there are some movies, and those movies get, again, ‘weird,’ and often those of us old guard, back in the day, used to be seeking an explanation for what the hell this is and what it meant. People wanted to know, we asked questions, we posted theories, we argued about their potential veracity, and then college ended for several and they just moved on with their lives, leaving behind whole books’ worth of information. Some people saw Evangelion as a thing that needed fixing and created books worth of fanfiction, and some saw it as a work that was deeply sonorous, an intense and thoughtful piece that people got mad about because they didn’t ‘get’ it.

One of the things that Evangelion, as a body of work, taught me, though I didn’t quite get it at the time, was that it was possible for an author to be wrong about a work. Not arrogantly, as in, I had a better insight into the work than Anno did, but simply and sincerely – it was possible for an author to say things about their work that didn’t make sense.

I was for a long time obssessed with the idea of getting Anno to ‘explain’ Evangelion. At first I assumed the movies finished the story – they don’t. They tell a different narrative. Then I thought maybe the dubbing had ‘changed’ the story and the subs were the more true version of the narrative – they don’t, not meaningfully. Then I thought that there was some sort of deep kabbalistic knowledge that I, a child who at the time had access to actual real world Christian conspiracy theory books, was uniquely positioned to unpack with numerology and science.

Repeatedly, I found myself at an unsatisfying nowhere, my interpretation of the series shifting each time. Did I miss something? Well I couldn’t rewatch the show because it was screening on TV and I wasn’t taping it. Next time around. I read online resources, borrowed manga, I tried to put the story together, and every time I got closer I found more information that proved to me that there was more to be found and some problem with the extent of the ‘canon’ as I found it.

An added factor in this endless yearning for an explanation on my part is that Evangelion is one of the most prodigiously merchandised things in the world. It is a brand that seemingly has an officially branded everything as far as consumer goods go – indeed, Red Bard has done a lengthy video exploring that. That’s a part of the problem of talking about it – because Evangelion was always not a story made to express a point but also a piece of media entertainment designed to generate a profit. As long as the story endures, as long as the interest persists, there will always be more ways to merchandise it.

It’s not on Netflix now as a way to get people to experience some grand classic, it’s on Netflix because that’s yet another way in which Gainax have been shown they can make more money on this product. Try to bear that in mind – because if you want to think about the author, or the motivations of this work, you are absolutely going to discover that those motivations are infinitely cynical.

I think I was five years an Evangelion fan before I finally hit upon the truth of it: There was no truth to be uncovered because there was no truth to the work.

People are sharing their stories about how they first watched Evangelion and why you should too, and often it’s framed in terms of dealing with depression or sexuality or gender, because all the queer kids of the 90s who got to see this weird show dubbed on TV grew up, and because those were the most pressing things going on in their lives at the time. That’s not to say this is a series that lacks some meaning from those emotional axes – not at all. But if you were a black bisexual girl in the 90s and Evangelion was something only for you that wasn’t making you feel worse, it is 100% understandable why you were able to tell your story as it relates to this one.

I once said that Voltron is a ‘half full story’ – and Evangelion is too. But while Voltron makes all its characters and their storylines into bold, basic archetypes so they can focus on intense moments and let you fill in the motivations, Evangelion is half-full because a hole has been blown through it, a massive rend where story had to be taken out and replaced by what could come to mind for a man grappling with depression, building on themes he’d laid out that he honestly didn’t know or care about that much beforehand.

Where Voltron is smooth and safe for every interpretation, Evangelion is jagged and brutal and sad. It spends much of its time asking questions and repeatedly shows the characters not having any answer for them; there’s no real grand thesis statement to the series, and a bunch of episodes just seem to do nothing, and the only seeming thing this series can do consistently well is set up and follow through on really traumatising stuff. It’s also kinda artisinal in the trauma – one of the go-to traumas of genre media is openly sexually threatening or harming women, and this series kinda doesn’t do any of that, but it just piles on thousand yard stares and emotional breakdowns.

By the way, I’m not trying to run this series down. It has a bunch of cool stuff in it. It has a bunch of meaningful stuff in it. It makes some people really mad and it makes some people really happy. You could put it in a context of a Big Robot show, or talk about how it isn’t technically a Big Robot show. You could use it to talk about your history or how you learned about it, and yes indeed, it’s a series I can have fun making fun of for hours.

What matters the most, to me, when you talk about Evangelion, is that almost everyone who wants to talk to you about the series is trying to talk to you about themselves. About what it meant to them, about what in the series aches their curiosity, about why they’re talking about it.

Listen to them.