It’s kind of sad but as a young man I really had no idea what people did to make conversation. My earliest fumbling attempts to talk to people about things are these cringe-inducing things where as an adult I either waited for them to test me on subjects I understood from school, or, worse, tried to tell them about a thing from church that they had to know.

I was really obnoxious.

Anyway, one of the things I learned people talk about, is media they like. And that meant I had to try and share the things that resonated with me, and inevitably, the one thing in this vein that didn’t wind up bringing more shame on me was the work of Terry Pratchett. The problem with recommending Terry Pratchett is that Discworld, his largest body of work, is 47 books long, the ones at the start are kind of ‘wrong’ at representing the brilliance of the later books, but the later books make reference to a world that the earlier ones define, expanding on the complicated world that even Terry was kinda winging it through. No matter how excellent Discworld is, it’s not a book you can give someone, it’s a homework assignment. There isn’t a really simple, singular work to hand someone and say ‘this is a way to enjoy this author and learn if you like work they do,’ not in the Discworld books.

How wonderful then, is it to have the book Nation to share.

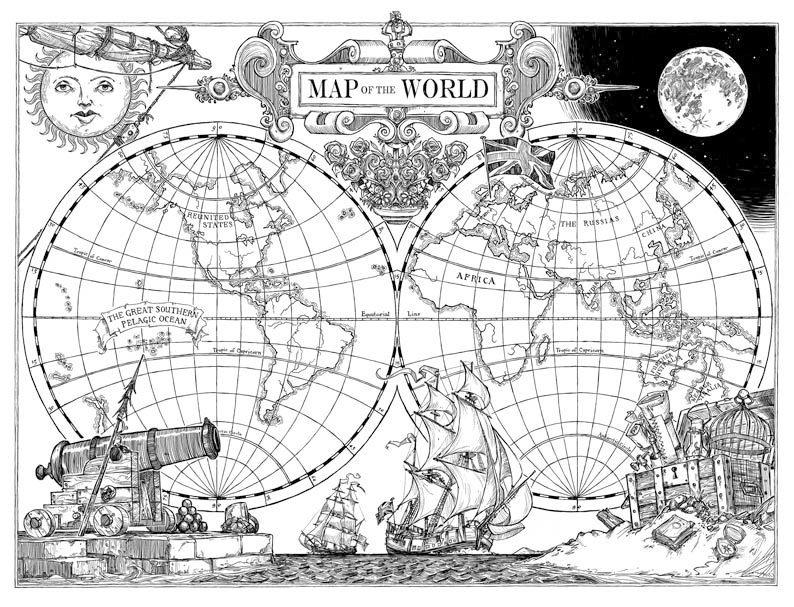

In the middle of the ocean, a tiny island is paying host to three lines of story. One story is the tale of a girl castaway, fleeing cruel mutineers. One story is the line of a king of empires, racing towards a missing heir. And one story is about Mau, a boy who was interrupted in the rite to become a man by the end of the world. A tidal wave crashes over the setting of this book, killing the captain of a boat, a line of communication, and literally everyone Mau knew. Then the story is about rebuilding a life and an identity in the aftermath of that apocalypse.

A novel’s not a movie – this isn’t a book where giving you an itemised list of what happens in it, in order, would be interesting and even then I’d have to miss some events for not being interesting enough but then I’d have to check what fits my vision of the story’s themes, and doing so would spoil a lot of the scenes that reinforce the powerful themes that fit in this dense, beautiful novel about castaways and castoffs.

I could tell you about the core characters of the novel, perhaps, those two central characters who kind of wind the whole story around themselves, and then wind themselves around one another (but not like that). There’s Daphne, who’s a British Girl of Particular Age For Adventures, but also is full of Good Stout Common Sense and espouses views Quite Like The Views Of The Author A Fair Bit Older Than Her. I like Daphne a lot, and her story is full of practical moments of refusing to be useless.

Daphne is easy to describe in terms of what she’s not, how she’s not Mau’s romantic prize, she’s not a more classical Enid Blyton character, she’s not foolish or giddy, but to do those things is to diminish her, in my opinion. Daphne is the kind of girl I’ve met, since I was no longer a teenager, and who can relate to me how very clearly they would have been glad to see Daphne in a book.

Daphne, at one point, in this book, kills someone.

It’s not a cheap shot, it’s not a magical gimmick, and it’s not treated as untraumatising. Immediately after the very justified action, she asks, then begs, then demands for moral redress. It has to be treated that way, or it’s just murder.

Daphne is amazing.

The other major character is Mau. Mau is from an island nation in the middle of the Pelagic Ocean, and he sees everything he grew up with, dead. I mentioned that before but I don’t think I can quite overstate the significance of this character to me. Mau left the village to do the manhood ritual – to find the circle of islands where the boys go, to leave behind his boy soul, and return to his family to be tattooed and exulted and become a man. When he’s returning, the world ends, and Mau finds everyone, and finds them dead.

This is tragic and existential. Mau is not only alone, which is tragic, but he is alone at a point in his life when he was prepared for something of great personal and spiritual significance. He left behind his old soul, and everything he believes, everything which should have kept this from happening, is now torn open and left aching.

Mau suffers a religious trauma, and has to make his life without any support for it, because there is nobody who can even understand what his trauma means.

I like Mau a lot.

I like how he does what he can with what he’s got left. And I like how he finds a reason to use what he experiences. He has to bury those of his old life, he has to mourn everyone, everyone. He has to care for those who wind up stranded on his island, because that’s what he should do. He argues with the god of Death, who definitely isn’t real. When the time comes, and there’s no other choice, he finds the old stones, that are the Grandfathers, and he rolls them away, in the name of saving everything of what is left.

Nation was written while Terry was dying – but then, weren’t all his books? – and was spurred in part by what he described as a religious experience. He heard his father’s voice – the man having long passed – while he was in the garden one day. Not given to supernatural thinking, and keenly aware that part of his problem was his memory shredding itself, Terry took that thought, and examined it from every direction he could.

Terry Pratchett died of a very similar problem to my grandfather. As he wrote this book, he described a problem, seven years before he died, where he had become a gramaphone that played a recording of his dad.

I hear my dad when I laugh. I don’t like that. I hear my Bible lessons when I reach for words to comfort people, and they make me feel bad and ashen inside. I don’t like that, either. In the dark of the night or the quiet of my home, when there’s nothing else making sounds, songs return to my mind, about how obedience is, the very best way, to show, that you, believe. The worse are there. They are tattooed on my soul

I recoil from calling myself ‘a man’ because I still think of myself as, well, a boy who’s winging it.

That, I don’t mind too much.

And I remember seeing my friends get baptised, which I never did, because I couldn’t in good conscience say I believed I was worth it. I think about the abusive place where I left behind my soul, and the hollow monster it made me.

Then I think about what I’m trying to do, without that soul.

And I go to try and roll aside another old stone.