And then like the krispy kreme, we’re back at it again.

It’s very hard to deal with contrary impulses and present a fair position without being coloured by the arguments you had on the way to get somewhere, or by the arguments you’re anticipating. For example, while I may say straight up that Fullmetal Alchemist: Brotherhood is probably the best anime of its type that exists (mage-punk, long-running action-adventure character driven stories with themes of war and loss), there’s still the hanging asterisk that I was also pretty positive about Fullmetal Alchemist, and how much can someone trust my opinion on this one? And what’s more, how can I praise that anime and yet have qualified praise for this one, because that was a Bad Anime and this is a Good Anime?

Anime fandom is a mistake.

Anyway, the coda: I think that Brotherhood is one of the best anime of its type, and yet, I think that has flaws that merit critical attention; I think that it’s worse because of the 2003 anime, and I think that anime is treated worse for not being this.

Let’s bust out an academic concept. There’s this idea from the 1990s from the work of one Gerard Geanette, who coined the term paratext to refer to media that is not of the work, but is the work surrounding the work; stuff that is not actually text to the work, but stuff that’s necessary to participate in the text, things that build up and become part of your text. Paratext is literally, in Geanette’s model, a zone, a tool you use to refer to a whole host of things, including book paper, printings, jackets, the room you were in when you read the book, and yeah most of his examples relate to books which is okay, because dude loves books.

Paratext is a term that when first employed wanted to talk about the way that the paper of a book changes the way the text reads, and then eventually spiralled out to underscore the way that media relates to one another and how we have paratextual industries like cosplay and fan media and like, things that let us reshape text with other text that was never partof the original text but now can be treated as if it was always there. Paratext is very powerful and it’s super cool, and Fullmetal Alchemist Brotherhood is an amazing work to regard critically because it has an entire other anime paratextual to it.

When you watch Brotherhood again, especially recently after watching 2003, you might be stunned to notice how often the anime seemingly makes a point of rushing past a tense bit you know won’t matter (Barry the Chopper’s appearance is a flying visit compared to the slow boil of the manga), and really marinate in the moments they know they can get a good pop with. This should make the work feel slimmed down, and if it had a consistently brisk pace, I might buy that, but it instead feels a lot more like this series is trying its best to hit points that have been focus-tested for maximal impact, but it wasn’t, not really. Instead, this is the anime being made as a response to fan demand, which means that when something is around too much, it’s because they were pretty confident fans wanted it.

Soooo, you know, Barry the Chopper as the live-in delightful serial killer and sex pest? Fan demand!

The upshot is that this series is one that wants to rush past stories you know and focus on stories you don’t, which creates the impression that this is an anime with a bloody reading list. It doesn’t care about doing a bad job of its Greed Arc (and it does a bad job of its Greed Arc) because it doesn’t think that part of its story matters. You get this rushed early story while it wants to sprint to ‘the new stuff’ and then when it gets there, it wallows. This zippy early and late slowness really ruins the pace of the story for me. Early on there are major plot points that aren’t given time to breathe, meaning that (for example) the death of Marta is basically a footnote, handled such that you know it won’t matter later even though the actual experience is incredibly traumatising for Al.

It also serves to codify the ‘Fullmetal Story Beats’ as a genre, with iteration #3, and don’t worry, we’ll get to that later.

Particularly of note, is that for all this series is again thoughtful and brilliant and clever and engaging and exciting and has a host of great exciting characters in it, this story’s conclusion drags. I don’t know how this series managed to make a climactic siege against double hitler with superpowers boring, but when the first seasons of the series play out like a recap movie, where if you ever feel you missed anything you can grab the other anime or the manga to check what you missed, the finale season then drops into thudding inevitability where when the anime has to tell its story on its own it’s still full of dramatic pauses and hesitation to let important, scientific, intelligent, and explanatory dialogue get out.

I don’t know how better to express it. The first seasons of this series play out like a recap movie, as if you should know all the details you’re watching in their appropriate sequence, and then it hits these roadbumps where it finally has to tell the story on its own and what ensues is a completely alien pace, a pace that makes it feel like the first series was doing a job of training wheels and explication, and without that, the storytelling apparatus is clunky.

The final season of this series, the final season, takes place almost entirely across the duration of a day. It culminates in four final encounters, and then at the end of the end of the end of them all, a godlike entitity steps in and tidies it all up and then we get an appropriate doling out of karmic punishments for all the appropriate characters, as filtered through the medium of pretty boys that are nonetheless not too pretty shooting wave beam cannons at one another. That vision of scientific and chemical cleverness just goes away in the name of, well, great big wave beam cannons until the loser of great big wave beam cannons gets great big wave beam cannonned wrong.

There are sequences in the finale that are very important because they’re the payoff for the appearance of a character who was introduced in one of those check-list rushes from earlier in the story, and yet if they were so pressed for time, they could have, you know, cut the character entirely, not introduced them, then not used them later. If your planting is a rush and your payoff is a drag, you might have mis-used your time.

There’s also a little more of the pressure of stupidity – the final culmination at the heart of the story has to come to a head, and that means that there are a few characters who do well-intentioned, easily-duped, incredibly stupid things, in order to make sure they’re in the right place at the right time (despite serving very little story purpose otherwise). On the other hand, like I said: If I was saying anime that ended badly can’t be good anime, there’d only be like, four good anime.

It’s fundamentally hard, though, to judge this anime fairly, certainly this anime fairly compared to the first anime, like I implied last week. It’s not just that they’re working off different source material, but that Brotherhood is being made with a full, actualised example of what a Fullmetal Alchemist Anime Can Look Like. It’s working from an extra example, a whole 50% extra source material, and that source material is the kind of stuff that storyboarders and directors and narrative designers are going to want.

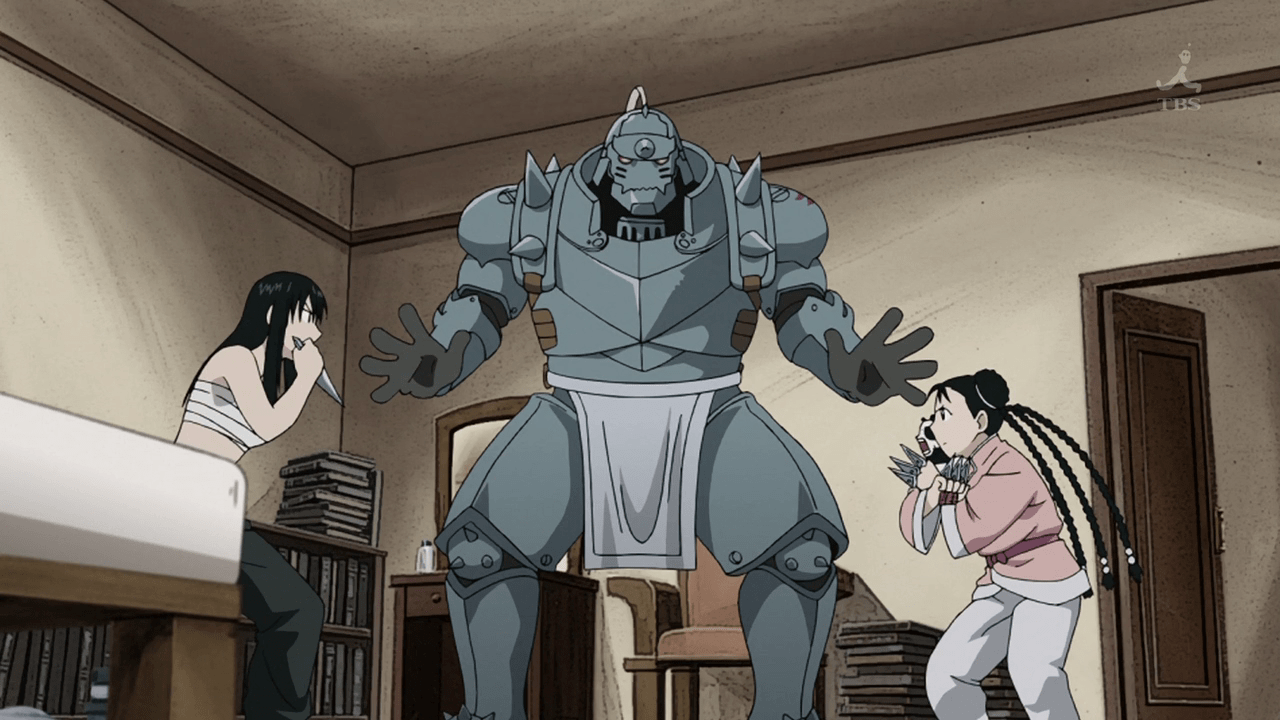

What stands apart, then is stuff that it’s nice to see in the big screen, and it’s a bummer to have missed out on them last time. Just as some examples, I do like Kaiju Envy, I like Greedling a lot, and I love him as the end point for the Greed character (and it fits him a lot better than the first anime incarnation of him that kind of wildly misfired). Selim makes an excellent Pride, this Sloth is also great because it underscores that not everything in this universe revolves around the same four people, which opens the world up and spreads things out, that’s great too. There’s more Hawkeye and more chance for her to show she’s not just a stoic Gunhaver but is also an extremely smart, competent spy. Lin Fan comes along with Ling and they both open up the world, and also Lin Fan is awesome and also not just more alchemy and guns.

This anime has Olivier, who I love a great deal, in no small part because it’s really nice to know where a specific anime character falls on the ‘would they shoot Hitler’ stakes. Olivier would. Multiple times. Then she’d draw her sword.

There’s a better treatment of how the Isvhalan genocide was a genocide and less of a war between two powers, and how the power of alchemy led to a devastated people to get devastated again by dangerous actors, in a very real representation of what happens to these kinds of places in times of war. PTSD is treated more seriously, which is also nice, and Roy Mustang has something to do (along with his squad) that makes that whole space a lot more fleshed out and not just a framing device for Sheska (bye, Sheska) and Winry to hang out in.

Anyway, I praised Brotherhood a lot up top. It’s great. Characters and design and the science of systems is as with the rest of these series, the absolute peak of the work. So what if I think the ending got to be let’s say boring on a good day, incoherent on a bad day?

It’s still one of the best examples of what it’s trying to do, ever. And I don’t know how I can critically examine this anime without it being seen as if this criticism is calling this excellent series bad.

Next time we’re going to talk about occlusion.