We’re going to do something a little bit different this time.

This Story Pile is going to be about the newspaper comic Cul De Sac, a comic I really like, but which is also, unlike other media I cover, actually kind of already represented online in its entirety as it is. Like, if you want to go read Cul De Sac, you can… just… do that. The other thing we’re going to talk about is Calvin and Hobbes, which Bill Watterson, the creator, has been similarly archived online, but also crucially, not by me.

Normally I break up these essays on media with pictures from the media in question, or youtube embeds or whatever, but GoComics lacks that functionality and while I could always take the strips, upload and offer them in the context of my own work and you know, review and educational purposes (which it is), I’d still feel just a bit of a dick about it. This is much as with the work of Gary Larson, who has asked that people not circulate Far Side strips online, and, well, they do anyway.

With that in mind, I’m making the conscious decision to not put any of the comic strips here in this blog post. Instead, I’m going to try and keep it short.

It seems one of those most millenially appreciated things is Calvin and Hobbes. There don’t seem to be any people who actively think ill of it, and it has a sort of whimsical approach to the future that many of us can grasp and appreciate and cling to while, you know, roaring hellscape. There’s also something of a ‘thing’ about it, how Calvin and Hobbes wasn’t just a big deal but it was also a big deal how it went out – Bill Watterson refusing to let his work be milked for money forever, choosing to Not Be Rich in order to keep his work the way he wanted it presented. It’s a very pure narrative.

But, if you’re a fan of Watterson, do you wanna know what he’s a fan of?

Cul De Sac is a comic in the same basic vein as Calvin and Hobbes, set later and weirder. While Calvin and Hobbes followed a kid who stayed somewhere generically eight forever, the seven years of Cul De Sac followed Alice, a four year old girl, and her family, who weren’t really dysfunctional or especially weird or anything, it was just, you know, life and the world as filtered through a four year old. It’s a comic about dysfunctional sincerity.

Cul De Sac is really funny.

I think the thing about Cul De Sac that makes it so funny to me is that the artist, Richard Thompson, was capable of a certain kind of separation of jokes; he could deliver a punchline in a strip, then a different punchline for a different joke, without the two jokes feeling smeared together. This is a problem you can find in work like Arrested Development, where a single well-delivered line by the right person can’t feel disconnected, can’t feel like it’s its own joke, meaning that you’re often left feeling like you missed something. The nonsequitir of Alice’s four-year-old vision of reality is totally different to that.

There’s only seven years of Cul De Sac to read in archive, nothing compared to Peanuts or For Better or For Worse or the forty years of Garfield. It’s visually interesting, heartwarming, genuine, funny in a very low-key snort-through-the-nose kinda way, emotionally resonant, and repeatedly takes opportunities to flaunt what a skilled artist Richard Thompson was.

Was.

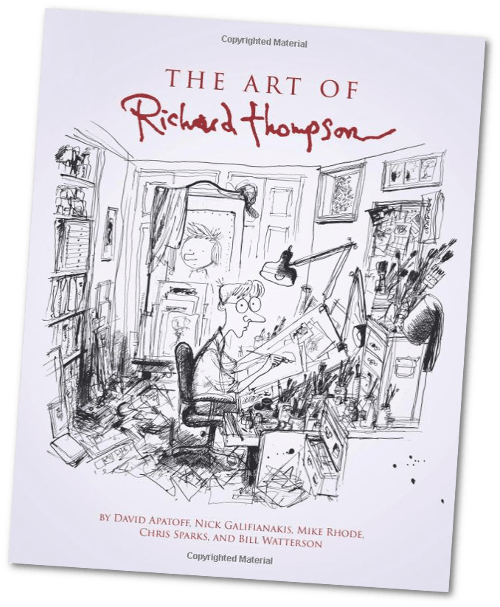

Richard Thompson, the artist behind Cul De Sac, passed away in 2016, after a battle with Parkinsons Disease. There are collections of his work, of his art, of his comics all over the internet and you can go look them up. And you should – he’s funny, he’s really funny and in many cases his scribbly-ass sketch style vanishes as he replaces it with a wholesale excellent simulacra of someone else’s style, to make sometimes the most jagged of points. The man was really good at his craft. But that’s what I think, and I’m nobody special.

In Dilbert – of all things – there’s this running gag centered around the garbage man, who is a super genius. But he chooses to be a garbage man, occasionally fixing things Dilbert built and handing them back to him, seemingly with no interest in that it annoys Dilbert, or that he could use that to make a profit. The choices of this character are left wholly inscrutable, but it is repeatedly underscored he’s not stupid. He’s not weird. He’s just really, really smart. He’s a garbage man because he chooses to be a garbage man, and the fact that doesn’t make sense to us is meant to be part of the joke – after all, he’s way smarter than we are. The idea is that genius sees the world differently.

Bill Watterson saw the world in a way that let him create Calvin and Hobbes. And he loves Cul De Sac.