If you’d told me that Netflix were putting together a Castlevania series by Warren Ellis and it was an Anime I’d have to have assumed you were working through some sort of nerdy fanboy madlibs, like the output of a twitter robot designed to generate quote-tweets from people inclined to go ‘omg that’d be great.’

It’s such a confluence of edginess; the game is not obscure, but it’s sub-mainstream enough to seem a little edgy. Netflix are by no means a small production house, but Netflix original animation is certainly not on the level of houses like Disney. Making an anime as a specific, separate genre of thing, is also, again, not actually not-mainstream, but seems non-mainstream. And then you throw in Warren Ellis, a man who’s produced tons of comic books and the licenses for tons of movies, and even a TV series, a man who has been kind of all about being the not-the-mainstream version of mainstream comics for large chunks of his career.

Warren Ellis is almost perfectly positioned as everyone’s second favourite comic book author; excellent and creative, but also so aggressively Very Online that you could be forgiven for thinking he’d sprung from the fever dreams of the internet itself. Ridiculous and posturing, energetic and digital, he’s also somehow managed a career as long as his without actually massively embarassing himself on issues that comic book authors didn’t seem to realise mastter that much. There’s no lingering false vision of his work like Mark Waid has, no uncomfortable sensuality of magic that Grant Morrison has, and unlike Akira Yoshida, Ellis exists.

He is the Patrick Swayze of comic book authors; great but so often overshadowed by excellence. You need to know comics to know Ellis and you need to know why Ellis hates comics to love them like he does. Ellis is a great big pink sparkly mullet of an author in an industry peopled by people trying to get themselves taken Very Seriously when they write about the spangly man in the cape with the funny knickers.

This set of factors, coupled with people talking about how brief the first season of Castlevania was pushed me away from it – it seemed that three episodes of NES-era narrative via Ellis might be the perfectly sized dose to completely blow the minds of people who had no real familiarity with any of these factors, that the sheer surprise of the series would set people off, have them curious for more, without it actually being in any way a necessarily good or enjoyable experience for those of us who knows what it’s like to wait six months for a comic issue that’s been A Bit Delayed.

Then I watched it, and…

Oh boy, is this the Good Shit.

You know an artist by the medium they work in. Alan Moore infamously resisted the idea of making his books into movies, because he felt that doing so required them to be in a fashion, ruined. It was his position that the nature of a comic panel, as a static image you could scrutinise at your own pace and composed in relationship to other components of the page, you told a different story than if the images moved. Yet there were people who persistently treated the comic book as if it was a storyboard, seeing the similarity between the two, while failing to tell the reason they were different, what meaningful change that asked. Alan Moore feels (? he might have softened in recent days) that the comic, as a distinct art from the movie, should be kept separate, and attempts to translate one into the other diminish the comic.

Warren Ellis is not a man who has been given to the same sort of moral compunction, the same boundary of craft. Numerous Warren Ellis works have been made into movies, some faithfully and some extremely not (looking at you, RED). This isn’t a conversation about whether or not the artist who cashes a cheque is bad or if someone is well or poorly suited, though, in a much more straightforward way, this is about how Castlevania reflects the skills of the man credited as its author.

Warren Ellis is good at giving comic artists clear, bold direction; breaking down complex actions into single beats; and deliberately distinctive character voice. You’ll see all three skills displayed here in Castlevania; the fights are often best viewed not as a complex field of events happening all at once, but a flow of storyboarded events, this-then-this-then-this and when they break down into one singular event happening, that event is much more about shifting focus from actor to actor in that sequence. Character dialogue is sharp and distinct, with the major cast of about eight characters all delivering lines that wouldn’t fit coming out of anyone else, and which reflect personalities that bounce off one another delightfully.

Character is what pulls this whole thing together, too. Castlevania as a property has ‘plot’ and it certainly has a story, but it’s hardly a unique one; Dracula has arrived with his castle, wrecks stuff, heroes go mess him up. Indeed, the way a videogame is typically presented as a long, slow journey through an impossible sequence of monsters and fights is sort of the opposite of good storytelling, because watching without doing all that becomes a slog. Rather than slavishly present that sequence, Castlevania instead uses its time to show us characters: who they are, what they care about, and how they solve their problems.

It’s great.

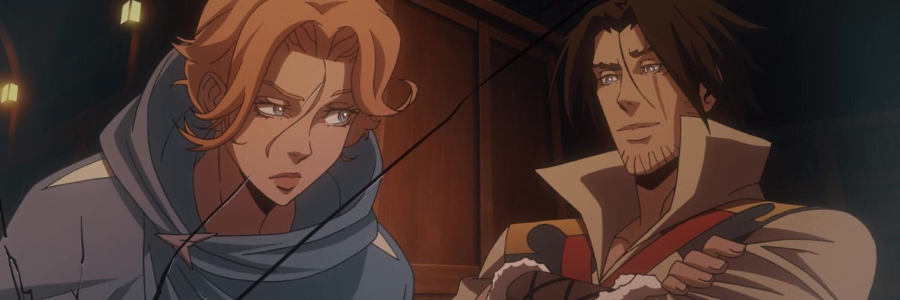

At first the story follows Dracula, and why he might be interested in becoming a supervillain. Then it moves on to Trevor Belmont, shows you the world he lives in and the kind of life he’s permitted, as a Trash Belmont. By the end of the first ””’season””’ the pieces are in place: You have Trevor Belmont, Alucard, and Sypha, and it’s this tryptich of personalities that makes this series so good.

A good character dynamic is one where if a group of characters removes any members, the remaining characters behave differently, but still interestingly. In Castlevania you have a standard set of archetypes; a hot mess, an erudite ponce, and an inquisitive imp. When any of these pair interact, how they treat one another and how they treat the absent one. Do they gossip? Do they try and understand them? Are they invested in that person’s inner life, and by talking about that, do they show us their inner life?

And what about what got me watching this? Well, I’m not too proud to tell you that I’d actually not bothered to watch the second season of Castlevania because a woman I know described a sequence as being violently hot, which prompted me to renew my interest. After all, I knew the series got gory, but I wasn’t expecting it to get awesome. I wasn’t expecting the incredibly satisfying violence, or the way people came to terms with what Dracula was actually doing. I was sure as hell not expecting its final scene, which messed me up pretty badly. Even if I wasn’t expecting that, though, that’s all stuff that could be expected in a series of this type. Some adventure, some violence, the inner life of the monster Dracula, whatever.

I wasn’t expecting a chat about Trevor’s name’s origin. I wasn’t expecting the shot of a baby vampire skull. I wasn’t expecting the way that the gore and violence of the demonic invasion was made infrastructural: People weren’t just dealing with invasions, they were dealing with invasions they had to clean up after. Mass death and weirdly real acts of surreal violence were shown to be things that are done by people, to people, and that action has consequences.

But okay, so the series is good. Comic book inside baseball and stuff. Whatever. You don’t care that I care about Warren, Ellising. Lords knows that’s not enough reason to check it out.

What I want you to know about in this series is Sypha.

The Castlevania games are let’s say a bit weak on representing women. Perhaps because the original genesis point for the series is basically a Boris Vallejo painting making out with a Frank Frazetta painting, it’s always been a series where you’re more likely to see a woman’s disembodied head as threatening to bite off your phallic object and drain your vital essences than, say, have a conversation with one. The character of Sypha is, in this series, pretty much invented out of whole cloth for the series.

And she rules.

There’s this tryptich I’m fond of noticing in stories, because it’s very satisfying, where three characters doing something together, can all be treated as essential to the experience in terms of doing, knowing, and being. If one character is all three of those things at once then the scene is weaker – you might as well not have the group. To use an example (from the Dragon Prince, another Netflix animated show), when three characters cross a lava river, one of them brings knowing (the knowledge of the path across the lava), one of them brings doing (leading the pathway across and visibly racing as the path fades), and one brings being (not threatened by the experience, but something about their presence changes what the other two have to do). I’m being oblique here, but it’s something I really like when I notice it. And in Castlevania, Sypha does a lot of knowing…

… but she also does a lot of being and doing too.

In its worst incarnation, the two-arguing-dudes-and-a-girl character setup is a bit B^uckley, a bit of two people and their nagging mom. I’d be lying if I said Sypha wasn’t to an extent a mom to the other two – there’s a point where she chides them and they respond with please, we’re not children, then immediately validate what she said. It happens. And Sypha’s characterisation is tied to the setting’s, uh

uh.

Look.

Sypha’s culture is kind of meta-textually-aware Jewish Traveller people. She’s shown as being powerful because she knows things. Her culture values knowing things. And that culture has an amazing summary, delivered as a punchline that still floors me as a way of examining outsider theology and I love it, and I love her. Sypha fights vampires and doesn’t flinch, she’s a mage who’s shown as doing things with impact rather than the more sparkly type of caster behaviour, and – and –

Look, I think Sypha is great.

Check this series out, it’s really great. And when you hear the line ‘See? God hates me!’ I hope you’re laughing as hard as I was.

1 Trackback