Talk about a mile-wide pie.

Bleach was a manga that started out in 2001, focusing – and I use the term loosely – on the adventures – and I use the term loosely – of one Ichigo Kurosaki, a Japanese high schooler who can see ghosts and discovers through a chance encounter one day that he’s on the precipice of an entirely different world with its own rules and traditions that he doesn’t understand where he has to fight all the baddies, get to the end, do the thing that resets the narrative for a bit and proceeds to do so for fifteen years.

It’s easy now to make fun of Bleach because it’s something of a punchline thanks to a repetitive story loop and a precipitous drop in quality and popularity towards the end that resulted in its anime being cancelled rather than just running out.

The manga once was one of the ‘big three’ – One Piece, Naruto and Bleach were at one point all competing for the position of most popular manga in the world, and Bleach alone has sold more than 90 million books in Japan, 120 million outside of it, and is the 6th best-selling manga of all time from its source, and something like the 20th best-selling manga of all time overall. Bleach, for all that it’s a joke, is a joke that’s absolutely had every form of commercial success you could want, including numerous chart-topping songs and albums, multiple movies including a live action one (that I’ve already written about, and really liked).

When I talked about Exalted (which shares more than a bit of a silhouette with Bleach), I remarked how the sheer phenomenal excess of that game makes it hard to sound like you’re criticising the game that sounds really cool. Bleach has a sort of inverse problem, where describing the plot or narrative of Bleach makes it sound like the series is just bad all the way through. Couple this with the fact that there are 686 chapters of this manga, three hundred and sixty six episodes of anime, and four animated movies, it’s hard to grapple with this absolute trunk of a franchise. It’s not just that Bleach is massive, it’s that Bleach is so massive that it kind of creates its own metaphysics. You can’t really judge Bleach on an episode-to-episode basis or issue-by-issue basis, because so much of what exists of Bleach isn’t the reason people engaged with it.

If you’re into Bleach or, more reasonably, if you were into Bleach and now aren’t, the attitude is kind of one of embarassment. It’s the Glee of the big three, an anime event that came and went and feels somehow much smaller than it ever actually was because of its ridiculously absentee ending. Bleach wasn’t something you watched, it was something that just kind of rolled through the culture and just happened and then when it was cancelled it came with a sort of confused wait, it only just got cancelled?

So few people were into Bleach when it ended, in my experience. Even I wasn’t, I tapped out surprisingly early in the overall run of the thing, dropping in to look at what Bleach was doing rather than necessarily watching large chunks at a time. When you look at Bleach like a series of puncuated incidents, and not the moment-to-moment action scenes and narrative beats of each arc, you’re left with the strange, impossible task of describing what happens in any way but as a series of loops. Once a season, Ichigo discovers an entire level of the world that he didn’t know about*, which has its own rules and requires him to rise to a new level in order to meet it, doing so in the name of recovering a maguffin (that’s usually a woman) and that’s all really boring.

Except that *.

See that *?

What that * represents is this new level of world is then shown through character introductions and world building and cool moments of characters showing you who they are, often in the best way that Tite Kubo can.

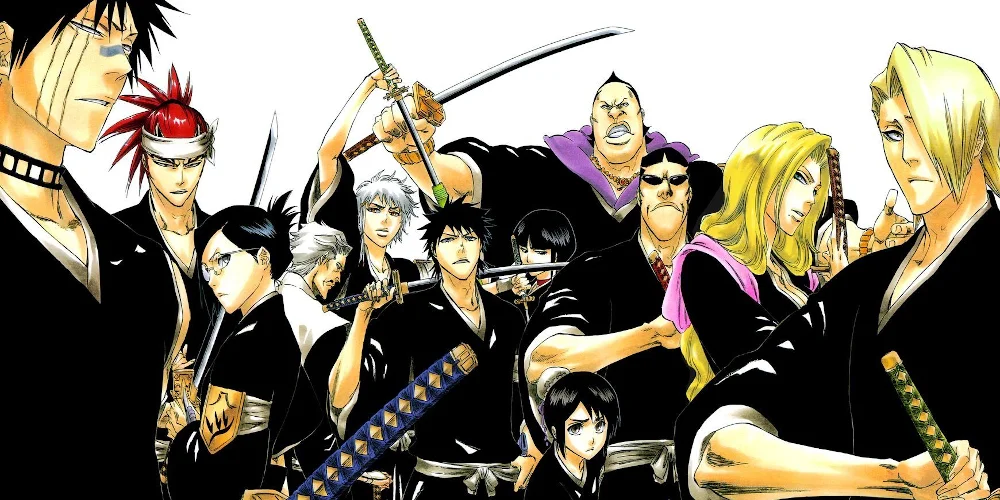

I mean it, Tite Kubo is an amazing creator when it comes to the work of conveying character design. It’s partially just good artistic skill, refined and redone, but it’s not just drawing the character in a way that looks good and interesting and different. Kubo’s designs are then brought to light in manga panels or translated into anime frames that are meant to convey to you not just how these characters look, but who they are, and that means that Kubo is someone whose greatest skill is making four or five seconds of time feel great, pushed into a creative format that ran for fifteen years.

Kubo is, without a doubt, an amazing artist. When he has the time to create and the opportunity to frame that art, and the time to recharge his interest between the creation of that art, he’s consistently created great work. In a story world where literally everyone is some variety of sword fighter he was able to make combats full of interesting, visually distinct poses and interactions. Again, this is a guy who can make five seconds of a story amazing.

That ability to excel in the tiniest windows of time shows in the things that Bleach does amazingly. Promotional art for the series shows characters in a variety of outfits and scenarios, rather than just the same ‘iconic’ looks that the medium tends to favour to save money. What’s more, variety of aesthetic is a huge challenge, when you’re dealing with a cast of characters like Bleach has. The normally effusive TVTropes wiki explains the cast of Bleach on their ‘characters’ tab with just the line: There are so many they occupy twenty pages.

Usually I’ll talk about what ‘matters’ in a story, talk about things the story wants to do, or a point it builds to. This tends to be what really sours me on work, if the conclusion the story’s all about turns out to be bad, or shows that what I thought was going on wasn’t really going on. You can look to my review of The Saint for an example, where a movie that seemed to be about a cool dapper rogue struggling against a conspiracy just turned out to be PATRIOT act pornography.

Talking about what matters in Bleach is god damn nonsense because the series was never really made as something with an end, with a place it was going. Tite’s talked about it – in fairly couched terms – about how he didn’t like the editorial relationship he had to the workload for Bleach, producing a high-quality weekly manga on the budget he had. Manga is largely the result of a grind, and the people who last in it are people who can handle incredibly high demands and constant pressure and job insecurity, and oh, their work can be directly destroyed by the process of doing the work where fine motor control becomes harder.

This means that mostly, Bleach was about laying track in front of a moving train, and that track had to not just be stuff that the audience reacted positively to, but also let Tite do the stuff he liked doing. Since he liked character design, that meant he had to keep introducing characters – which was very doable, if you needed to keep introducing enemies and allies and all that. Of course, if you’re churning out whole sets of characters, you’ll start to see the similarities – the way groups consistently featured archetypes that echoed one another, with Ichigo / Renji / Grimmjow as one of the first easy examples of a ‘hot head with a lot of power introduced to look cool.’

It kind of works though for the series benefit that it doesn’t have a general point. By the end, Ichigo is a kind of shattered vessel of a character. It used to be at the start of the narrative he was a secretly bookish school tough who wandered around town being nice to ghosts and starting fights for reasons others thought were inscrutable but tied to the supernatural, with his unexplained orange hair and his overly enthusiastic weirdo of a dad. By the end, Ichigo existed to Get Stronger so he could Defend His Friends, and his strength wound up being tied to literally every type of supernatural force, meaning that his choices and personality weren’t really important any more, as a sort of ‘point zero’ for supernatural nonsense.

Without a greater point, then, you’re left with what Tite creates best. Moments. Single conversations. Single scenes. Character ideas rather than characters’ narratives.

I think my favourite example of Bleach doing Bleach stuff is the Zanpakuto. In the first two arcs of the story, it explains the idea that your soul has a weapon and that weapon has unique abilities based on who you are. These abilities are some good, high-scale X-Men style bullshit, too. We’re not saying ‘this one disarms good,’ we’re talking of things like ‘this weapon can make people who see it see perfect illusions.’

This makes them perfect for short storytelling. It’s a weapon that materialises and metaphorises something about your personality, about who you are. You get to use it (because battles are how characters interact in this world), and while you use it, people get to see how that means you’d approach battle.

Renji’s weapon is an immense chain of blades, jagged and swirling – it lets him create a storm of violence around him but means that he’s more of a ‘cloud’ of violence than a specific person. Ukitake and Kyoraku both have zanpakuto that become two weapons (which is a bisexual culture joke all of its own). Hanatarou’s blade heals people. Kenpachi’s Zanpakuto is a broken, jagged stick of a thing because he’s always pushed to the ragged edge looking for violence. Komamura’s is a hecking kaiju. Favourite amongst them all for me is Kira, whose sword doubles the weight of whatever it hits, meaning fighting him was all about grappling with an ever increasing burden you couldn’t handle, representing the weight of his personal anxiety over violence.

What then about Bleach mattered?

Well, all of it mattered. If watching Bleach was your full time job, you’d restart the series once a month. You don’t get that kind of volume if nobody cared. There was a sort of devil’s pact for the long-term watchers, the belief that there was something at some point, far in the future, when you were done, when you got to the end that would make it all worth it, worth the delays and the filler arcs and the um-and-ahhing around what was going on, where the powers came from, why this was even like this… and all it had to do was end okay. People who were in for the long run were almost all, by the feeling of it, resigned.

Oh, it was successful all the way through. Bleach wasn’t just making movies and TV series and manga and merchandise, it was also making songs hit the top 10 in Japan every time they played one. If you got to do a song for Bleach, congratulations, you now had a hit. Every one of the openings and endings was cool in some different way, and presented a sound and style that was out of the normal type for even the actiony teen-oriented anime of the time. It was cool in a way that anime normally doesn’t get to be, shown again in that fashion and visual style. I guess that’s another one of Bleach’s virtues, another natural form its essence can take – that it can be the breath of life for the narrative as long as a music video.

It didn’t end well, by the way.

It never was going to. It did a timeskip, it burned down its setting, it shook up its status quos, and then, it… stopped.

When you don’t have a sort of concluding paragraph, when you don’t have a point you were building to, though, there’s a certain freedom to it. I don’t think Tite really had a plan and if he did it didn’t matter because the author of Bleach, in a proper Barthes way, is dead, and that author had no idea where they were going.

What then… with that in mind… what could matter in Bleach? I mean I should care about this a lot, shouldn’t I? I once mocked the Justice League movie for being two minutes in its two hours, but I plowed a lot more time into Bleach. I invested. I know the names of Soul Reapers and how their swords work (and there are lots of them). I know the lyrics to ending themes. I saved caps from this show to talk about them. I played in a D&D campaign set in this setting, and that, that right there is the core of it.

That is what’s going to matter.

Bleach is an RPG setting of a series. You’re given repeated doses of lore, and only the shallowest flash of the kind of stories that lore can be used to explore. There are sites for dungeons, ancient grudges, old forces, new ways that powers can interact, origin stories for types of characters and subraces and cultures that you can belong to, that you can imagine belonging to, but none of them are so explored or fleshed out to have ‘their story’ told and resolved. A serially incomplete narrative filled with interesting moments of expression and design, Bleach is the kind of RPG sourcebook that can only come from someone whose most excellent skill is the expression of a character in the tiniest of moments.

Make your character, pick an origin point for them, pick a home turf for where they hang around, give them their special weapon or special power, give them a cool mask if they need it or a sword if they need it. Talk over with your GM about the mid-game upgrade you want to have when the situation calls for it. Pick a few characters to work with as backstory elements. Spend your points here, and we’ll meet on Friday nights.

I feel like if Ranma 1/2 hadn’t been my Ranma 1/2, Bleach would have been my Ranma 1/2. It’s an anime that gets to be creative and expressive over and over again, with its steadily inflating cast. It’s a lot like Dragonball, where a narrative following the main protagonist has to keep shifting to keep the author from getting bored, and introduces new characters and ideas on the regular to keep the audience from getting bored. Except Dragonball introduces ugly bricks of duh, and Bleach kept introducing expressions of the adolescent fear that adulthood was just about to happen to you and you’d have no idea how to finish anything or tell your editor you need a break.

I really love Bleach, but I don’t recommend it.

This article draft is two years old, good god.

1 Trackback