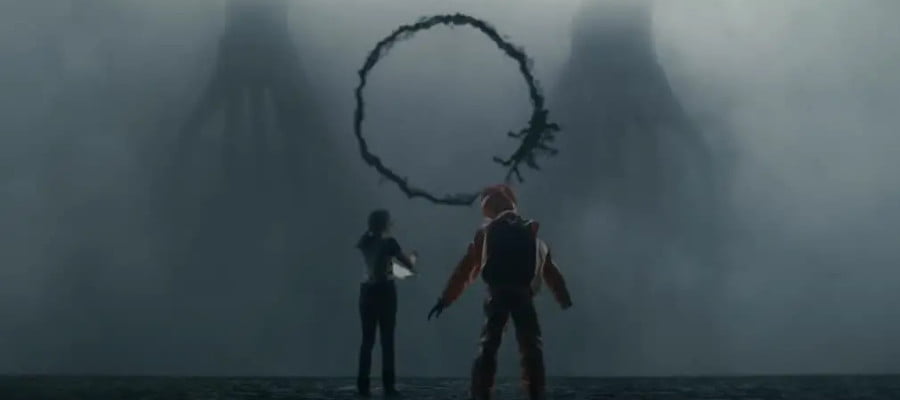

Arrival is a 2016 movie about the individual experience of a very thoughtful linguist lady as humanity contends with the first engagement with an alien first contact, not in the vein of guns and bombs and tanks and planes, the way Will Smith taught us, but instead, the high stakes, deeply intense world of complex linguistic deconstruction without an existing linguistic frame of reference. And it whips, but it’s also like being bathed in wax.

It’s a language nerd movie, but I’d leave the detailed considerations of that to other people, you know, people who are experts in language. I’d recommend checking out Lingthusiasm, which goes in on the movie in depth. I’m going to try and avoid replicating anything they cover here. The only thing I’d point to that stands apart is the way that this movie demonstrates how weak our language is to discuss language we don’t have.

Don’t worry, I’m not going to talk spoilers after the fold. There’s probably some generalities that can give away things ‘about’ the movie, but instead I want to talk about what this movie thinks is reasonable and normal.

Anyway, if you’re curious about the general overview, the kind of thing you want to hear out of a typical review, well, I guess the first thing I’d point to is the way this movie’s soundtrack is deeply affecting. It’s this weird mix of sounds and silence that are designed to feel unnatural, designed to not sound like ‘music’ as we understand it. At first it comes across as unsettling and creepy; slowly the sounds transformed in my experience to being instead a sign of curiosity, of helplessness, and eventually yearning. It’s the thing I remember, over and over, when I think back on the movie.

It’s even more remarkable when I consider that I should be able to remember the actress that drives the story. Looking it up, this is a movie that features Amy Adams, Forest Whittaker and a bag of hair with a flat nose, but I couldn’t bring any of their specific ideas to mind. It’s possibly a good thing, the way that the story just tangles around the whole narrative of the experience, in a way that any individual character becomes less important than the whole.

Which is kind of the point, I guess, to that narrative?

It’s a slow one. I found that this was a movie with a very, very deliberate start. At the time I described it as gracious. There was a way that the whole experience was slow and careful about everything, as it bit by bit crept along and showed people trying to react to the interactions of their ordinary lives being bent around the strangeness of the events. There’s the way sunlight of the story slowly creeps under the door, until eventually it’s so hard and hot and blazing that you have to confront it face-on.

Arrival probably annoys chuds in that there’s an importance on other countries, but also has other ways to appeal to those chuds, in that the other cultures are the ones who we primarily get to see in terms of how they want to do things involving the aliens that our protagonist doesn’t. Basically, you can point to ‘China’ has problems, and you can point to ‘a Chinese character is responsible for saving the day,’ (oh come on, that’s not a spoiler).

What Arrival puts me in mind of now is the much more interesting question of what does an international reaction to a global incident look like? Back in 2016 when the movie came out, the idea that something could impact twelve countries, and the whole world would connect and work together and strive to address the complexities of it, with tensions of the observers holding their breath for both positive and negative reactions? That idea didn’t have a strong, recent example for post-Soviet Union global responses.

I guess the nearest example in my lifetime of ‘something went wrong that everyone needs to care about’ was probably Chernobyl. 9/11 was definitely important, in that same ‘everyone is holding their breath’ way but that was a very political entity; the problem was other people and the question was who history was going to turn around and sit on. Chernobyl by contrast, regardless of how it happened, was a problem that needed addressing by as many people as could contribute anything, because it didn’t matter where on what border you rested as a political entity, the reactor would pump out radioactivity until everyone was dead and then keep going because it didn’t care.

In that regard, the idea of a complex scenario like ‘the whole world is suddenly paying attention to an alien first contact scenario’ tended to not get framed in terms of lots of people all at once. Alien first contact in stories of my youth tended to be about single loners and very, very rarely governments. If governments got involved it was because they already knew about it, usually. Independence Day wanted to frame itself as an international, multinational response, but if you believe that, you’re probably very, very American.

That was in 2016, when a movie could come out assuming that a complex, delicate scenario like this could be handled by lots of countries locking things down and examining a difficult problem in a complicated way. That the solution could come from how we interact as a world.

You’ll hear a lot of talk about Arrival that wants to be about what the movie is, as it were, ‘about.’ Without talking about those things, though, I thought it was interesting to look at the way that this movie is about the thing it’s about. It’s a story that sees a hopeful vision of humanity, presenting our worst self as our own inability to trust a stranger and our inability to trust one another, but it’s still built in a place where when a problem happens, we bring to bear the greatest minds with the most appropriate skillset to try and fix it.

Now, I figure there are a lot of people who would just argue that there weren’t any aliens at all.