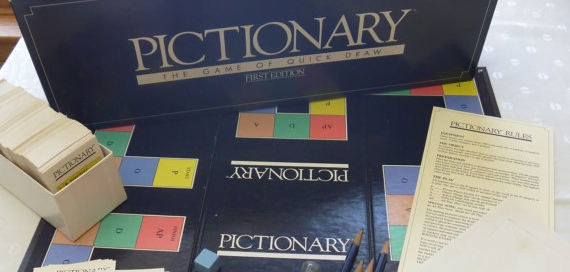

If you’ve played Pictionary in the past ten years, hold on, just, you know, hold on.

Okay, so I played Pictionary when I was a little kid visiting friends a thousand miles from our house. It was not a great game – I never was that into it, I wasn’t very good at it, and it had a board that you had to roll and move around, which meant there were often long periods where you were watching people do five or ten minute long ‘turns’ while they bickered and argued about the drawings and so on.

Similarly, one thing I try to do now as an adult is think about old games I played, and if I can improve on them. It’s very basic, methodical kind of work: What did or didn’t work about this game? What failed, what succeeded, what needs more attention, what was just always going to be bad? Can these mechanics represent something else? Crucially, when looking at older board games, I ask myself: What can be taken away?

With Pictionary, the idea I had was that the first thing to take away is the board.

Right?

You have a deck of cards, they give you secret information, that’s heaps, that’s all you need. You can even use the cards to do something random, but, you don’t even have to. You can make the game about rolling a dice and looking at a card, and right there, you’ve got a rudimentary design.

The idea I belted out was as follows:

- The game is played with drawing paper and tools, a deck of cards, and a dice.

- On your turn, you roll a dice, look at a card, and then that card presents you with a number of options, with your number roll giving you a priority.

Each card has seven options on it; one in each of the categories – let’s say they’re like:

- Person

- Place

- Animal

- Object

- Action

- Internet

With another category that says Bail.

You roll the dice, you pick one of the things to draw, and if you draw the thing that the number rolled, the card’s worth bonus points. This way you’re pushed towards an option but not screwed. There’s also the ‘bail’ option where if none of the options are good, you can offer this card to the whole table so everyone can try and draw the ‘bail’ option.

Just like that, I have the outlines for a card game. The timer becomes a problem! But a physical timer, a dice, and a bunch of cards takes up way less space than a big board would and you could fit the whole game in a tiny space, almost Oink Games style! Or you could make the game print-and-play, or even give out a template for people. And if you’re a teacher, you can just use a big ole list of random flash card words where they have to draw the thing, then write the name to show they get what it is! Teaching supplies probably feature whiteboards and markers, so you can repeatedly use the same drawing space over and over instead of paper and pencils!

Would I make this game? No, probably not. It’s not a terrible idea, and it certainly seems doable very easily, and may even sell a few copies, but the nature of it is that it’s just making a shelf filler.

Now.

The punchline.

Turns out the copy of Pictionary I played in the 1990s was from… 1985 or so. The great big box, the board, the roll and move? That stuff’s not really part of the game any more. In fact, if I’d looked at a copy of Pictionary from the last ten years, I’d find a game which is just cards, dice, timer, and whiteboards and whiteboard markers.

I choose to think of this as convergent evolution, of sorts, and that’s kind of good. It’s definitely for the best – it’s a way to show that Pictionary with a board can handle losing the board. What’s more, it also shows what I was considering and experimenting with: I wanted to deal with chokepoints and friction. That’s great, I can deal with that.

It doesn’t fix one of the biggest problems with Pictionary, even as it reduces the game design I’d made to a super-simple, tight version that I could probably sell for $15 with hundreds of possible game states (Which seems fair to me). What it doesn’t fix is that if you can’t draw, this game sucks.

Fortunately, Pictomania, by Vlaad Cvhatil, does solve that, by making the drawing and solving concurrent; you draw until you’re as good as you’re going to get, then you do your guessing – and guessing correctly first is more valuable than getting all your work guessed perfectly. This creates a tension for drawing ‘as well as you can’ but being okay when you stop.

1 Trackback