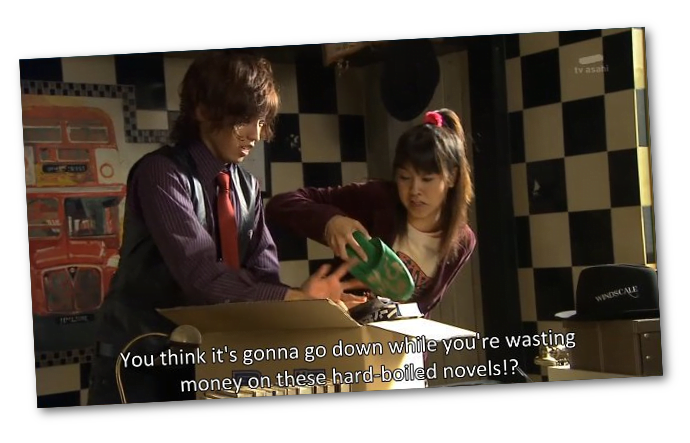

In Kamen Rider W, they use the term hardboiled a lot, and they directly, by name, invoke the idea of hardboiled detective fiction. The books are shown in shots, around the home and office that Sokichi made, and Hidari later inherited. Sokichi names Phillip after after Phillip Marlowe, the character central to Raymond Chandler’s series of novels. It’s repeatedly invoked in the case of secret catboy Hidari Shotaro, where he explains why he does something as being the essence of hardboiled. The series’ theme –

which is awesome –

is called WBX for DOUBLE-BOILED EXTREME.

Anyway, this series makes a big point of, with Hidari and Sokichi, referencing hardboiled fiction and it’s delightful.

It’s delightful because it’s ridiculously, hilariously, amazingly wrong.

Let’s explain ‘hardboiled’ really quickly.

First of all, hardboiled is a genre term coined by Raymond Chandler, describing the work of Dashiell Hammet, but which applies to Chandler’s own work. It’s often commonly seen as synonymous with or connected to noir stories, but that’s a bit of a conflation. Noir is a narrative about darkness, usually in the typical meaning but also in the emotional and narrative way and Noir is very French in root, while Hardboiled is very American. You can have a noir story that isn’t hardboiled, and you can have a hardboiled story that isn’t noir.

Hardboiled was about a style of story, and it’s in opposition to what’s known as classical detective fiction, you know, your Poirots and your Holmes and your Miss Marples. Hardboiled stories were the ones weren’t about parlour rooms and puzzles but were about occasionally punching someone in the throat. They were also the ones that tended towards featuring a lot of sex and violence, coincidentally because they wanted to be bought in magazines.

Raymond Chandler said that hardboiled stories ‘gave murder back to the kind of people who commit it for reasons, not just to provide a corpse; and with the means at hand, not with hand-wrought duelling pistols, curare, and tropical fish.’

Hardboiled stories weren’t about divining the correct answer to some elaborate puzzles, empty scenes you’re meant to scour for the detail being hidden in the backgrounds. They weren’t about murder scenarios, they were about murders. They were about the kind of mystery where if you never got an explanation you’d still read it, because the story was more than just a big construction for the final, satisfying moment of the revelation. This means that hardboiled characters, the characters that carry a hardboiled story, tend to be themselves crooks, or borderline near-crooks: they’re people who are usually acting in response to fundamentally corrupt systems, criminal networks and incompetent or evil police. You could go to the authorities when you’re wronged in a hardboiled story, or you could just lamp a goon, and one of those choices would actually have an impact.

One of the side effects of hardboiled narratives is that because they wanted to show you both a lot of sexy things and a lot of violent things, and put them in cool, interesting settings is that the hardboiled protagonist was someone who had to be able to ricochet around between a lot of different places. The demands of the scene and therefore the story created the hardboiled detective: an individual who, usually, had lived through an experience (commonly for the setting, it was the depression and prohibition, with a dash of The War), and been changed in a permanent way, a way that made them, well, hard. Yet to keep going to different spaces and make them feel real, to speak to the reader in their own language about the estates of millionaires and the grungy filth of speakeasies, the hardboiled detective had to be someone who could move between societies’ layers.

A hardboiled story is therefore one with a lot of sex and violence and usually following a broken man – and yeah it’s usually a man – who has some reason to belong nowhere and distrust almost everyone.

This is nothing like what Sokichi and Hidari talk about! They talk about things like manners and nice hats and dressing well and never giving up and never letting your client be hurt! Sokichi even explicitly says that Phillip Marlowe solves everything by his own choice. Phillip says that Hardboiled heroes are men with wills of iron who don’t let their emotions control them!

The show even brings out a Sherlock Holmes style Poirot-ass scene, which is the actual and literal antithesis of Hardboiled! The agency uses a network of informants that are meant to invoke Sherlock Holmes’ Baker Street Irregulars!

What then? What does this mean?

Hidari and Sokichi don’t know crap about the kind of stories they claim to read? Well, probably, because honestly, I don’t imagine anyone should be reading those books as a life guide. The nature of hardboiled detective is kind of fundamentally miserable.

Now, when you encounter a flaw in a story like this you have a couple of ways to solve it. You can take a non-diegetic solution to it; that these storytellers didn’t bother to do any research into hardboiled detectives and just borrowed the aesthetics. Or maybe you can take a diegetic one – these people are idiots. Those are kind of easy routes, though – one is simply discarding the incongruity and hoping the story doesn’t draw too much attention to it and the other diminishes the characters.

What harmonises these conflicting ideas to me is to look at Sokichi and Hidari and see what they saw in the Hardboiled hero. We assume they read the stories, so that’s a given. Then there’s the things they talk about a hardboiled character doing, or the kind of stories they’re about, and, crucially, these are ideas they are using to live their lives in the experience of being detectives.

It’s one thing for me to stand around going: Oh, Shotaro, you doofus, you clearly don’t know the greater metatext of all these stories. But so what, Robotech wasn’t actually a story about being willing to murder the evil of the past, but that’s what I took away from it as a child. This means that there’s something in those Hardboiled novels – and we know it’s the novels, we know it’s the fiction that these two people read because the books are all over the place – that they both took to.

What do they describe?

Men with wills of iron who aren’t overwhelmed by their feelings.

A city that has its own persona.

A world full of badness that the hero is always trying to fix.

Solving things through making choices.

There’s a fundamental fairness to the world of W that’s missing in the hardboiled fiction of the past. Hardboiled fiction was everything sucks, then you drink, with detectives broken down by a world of painful oppression that they forced themselves to stand up against, because that’s all they knew how to do. And crucially, the hardboiled stories were about characters who were cool, for their time, but to be cool now needs to be re-examined. They have to reconsider the hardboiled world, and its values, to make anything of the premise. Sokichi refused to let his clients be hurt, rescued lost children, came to the aid of women in distress and wanted to keep the entire world from suffering. He valued appearances and told Hidari to do so too – to become a person worthy of his presentation.

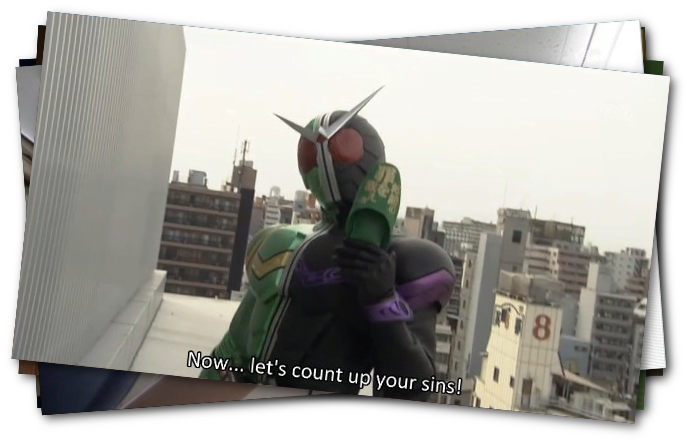

It’s a strange and rare synthesis: this take on hardboiled fiction is extremely superficial but in that superficiality there is a kind optimism. A willingness to take a hardboiled ideal of being personal, connected, willing to fight and able to talk to anyone, and then putting that in the hands of people who wouldn’t give up, wouldn’t break down, and wouldn’t compromise their ideals or commit to cruelty.

Don’t look to Kamen Rider W for a hardboiled story. But look to it for an example of the kind of story you would tell if you loved hardboiled stories, but loved people too.