Kamen Rider W is my first Kamen Rider Series and it owns bones. It is a high-energy series about loving a place, about wanting to live up to your potential, about found family, about the stories we tell one another, about legacies and respect and love and fear and about kicking baddies in the face and refusing to give up and there’s a motorbike which changes parts and there’s a truck that drives the motorbike around and –

I really like this show.

I was worried when I went into Kamen Rider W because it had been a gift from a family member, and so often when someone hands me something I’ve never experienced and says ‘I think you’d like it’ it goes wrong, and then I’m anxious about not liking it and then I have to circle around what I really think of it and it becomes this source of stress until a year later when I can admit, oh yeah, I didn’t like those socks, mum. Kamen Rider W was a huge series – 40 odd episodes! – and it was aimed at kids and it was a show in the Dudes In Suits Live-Action Superheroing At One Another genre, a genre that I mostly knew via Power Rangers and more 1970s live-action superhero stories.

Okay, but let’s give you the fast rundown first.

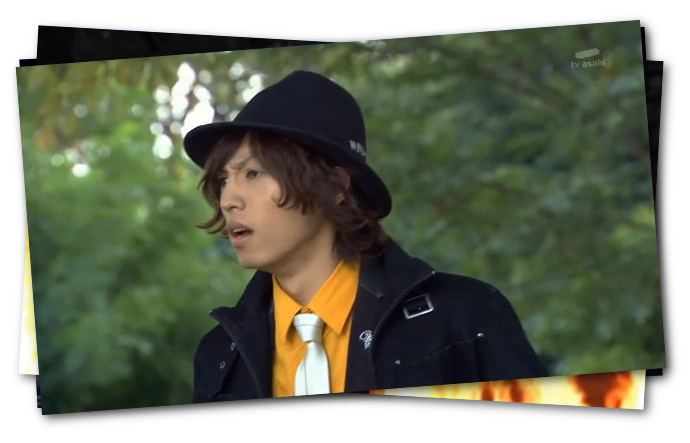

So the series kind of starts with Akiko coming to her dad’s old detective business trying to find him only to find this dork who owns a special hat carrier for his motorbike who has taken up residence in the business and he talks like he’s from a manga, and in the basement he’s keeping his Seemingly Just Normal Friend who gets totally obsessive about information and then they’re avoiding these monster things called a Dopant and when she asks him to explain, he starts telling her he can’t explain whereupon they’re attacked by a lava monster.

This establishes the dynamic where these three characters who are all on their own probably competent enough to handle all the problems in this city in their own way but are too wrapped up in their own nonsense to get around to it, and therefore need to lean on one another to help each other out, emotionally. The series goes on to collect a pair of J-pop stars, a couple of unlikable loser contacts, at least four cops of varying degrees of evil, a frog, a stag beetle and a dinosaur that roars like an electric guitar, as well as monsters whose powers are both alphabetically themed and connected to some vague idea of ‘the ancient past’ until such time as our heroes reach the source of the problem, and defeat it in A way that involves terrible loss to themselves, but they pull through, and it’s fine, it’s fine, it’s a good ending, I’m not crying, you’re crying, shut up.

I think the thing about this series that’s most astounding to me is that it has a level of craft and care it absolutely did not need, but which makes it really satisfying to watch as an adult, even though it’s still a show about a grasshopper-looking dude who jump-kicks people in the face. There’s a thing in storytelling, called verisimillitude, the impression of realism, that you’ll find kid-oriented media often misses.

Now, I used to be a fan of the Power Rangers, and now consider myself Someone Who Was A Fan of The Power Rangers. Power Rangers were very much aimed at a child audience and caught older kids by accident, and it shows in how that series’ verisimillitude fits. Powers can come and go as the plot demands, enemies can wildly fluctuate in their power or demeanour but it’s okay because the story isn’t dealing with people who think about the connections or ramifications of things they see in the story. The younger you are, the more you’re likely to see a story as a sequence of inherent moments and confrontations between things based on what they are rather than what they’ve done. The past is not important, the moment is.

By contrast, consider Stranger Things. This is a tv series about Lovecraftian horrors bursting through a wall between realities to attack a bunch of dorky kids who had a D&D game about basically them and features unrealistic things like telepathic children and nice cops and small-town weirdoes in America in the 80s being pre-emptively tuned in to The Clash, and the final encounter features a kid fighting a monster with a rock. Spoilers for Stranger Things, I guess. Yet despite the fact that Stranger Things happens in a world very much like our own, it all hangs together when you think about it. If you ask ‘hey, hang on, why did this happen,’ the story has an answer, and that answer will make sense.

The reason for this is structure, and I’ve talked about the idea of the single instigating event as an example of good structure before. What surprised me about Kamen Rider W is that this show that features themed USB drives that turn people into prehistoric fish, with at least three instances of precocious kids and twice featuring a detective trying to find a missing cat is that it’s rock solid, structurally speaking. There isn’t any New Thing Out Of Nowhere. There’s a coherent, consistant narrative through-line.

I’m not going to provide you with a point-by-point but if you’ve seen the story, you’ll find there’s a single incident, a disruption to an otherwise stable status quo, that makes the entire story start off. The status quote maintains itself as best it can, until all the pieces for what we see in W come into place, and then…

It spirals out of control.

This isn’t something a series has to have. But it makes the world feel more real, like a sequence of cause and effect, and more like our world. It means the things that should interact do interact, and it means that things that happened before you paid attention still made sense.

This is totally unnecessary for a kid’s show with a talking frog robot, but it does it anyway, and that attention to detail, that willingness to treat the subject matter seriously means that this very silly show about a boy’s quest to wear a hat is nonetheless taut, thoughtful, imbued with a coherent worldview and ideology, and emotionally very satisfying.

2 Trackbacks