If you listen to a PC Retro Gamer, and since you’re reading this, you are, then you may be familiar with certain gaming studios that were responsible for the enduring blocks of the media landscape of the 90s videogame scene. More than people may intuitively realise, companies often made an engine then made a host of games off that engine, meaning that Bullfrog Software made Magic Carpet and Gene Wars even though those are two seemingly very different games.

One of these landscape markers was Sierra Software, later Sierra On-Line, over in the PC-dominant format of Narrative Adventure. Now, it was a mistake to think of Sierra games as just the Kings Quest, Space Quest, Leisure Suit Larry, Mixed Up Mother Goose genre that they were, since Sierra also published ports from other consoles, like Atari Games’ Oil’s Well, and they imported a number of French games like the Gobliiins games which were also obscure narrative adventures, so you know, that’s not helpful. Point is, Sierra published a lot of games, including real-time strategy games (like Caesar), shooters (like Nova 9: The Return of Gir Draxon), business managers (Jones In The Fast Lane), and even mecha war games (the Earthsiege games).

But people mean ‘narrative adventures’ when they say ‘Sierra games.’

Wanna see when they released a Japanese action-RPG?

Zeliard is a 1987 PC-8801 game made in Japan by the company Game Arts. You might recognise that name as the makers of Thexder and Silpheed, which are the kinds of game names you may have seen in big collections, or praised by other parties. I don’t know Silpheed, and Thexder is a platformer with a transforming robot so I can understand why those are so well regarded.

I got Zeliard because it had a sierra splash screen and it fit on a disk, and you know, everyone pirated everything and it’s not a crime, and Activision’s mismanagement has way more to do with the death of Sierra than anything I did. I was figuring it was a Quest game like the other ones I loved (with my enduring favourite, the Quest For Glory games). What I was surprised to find was that it was instead, an exploration combat platformer.

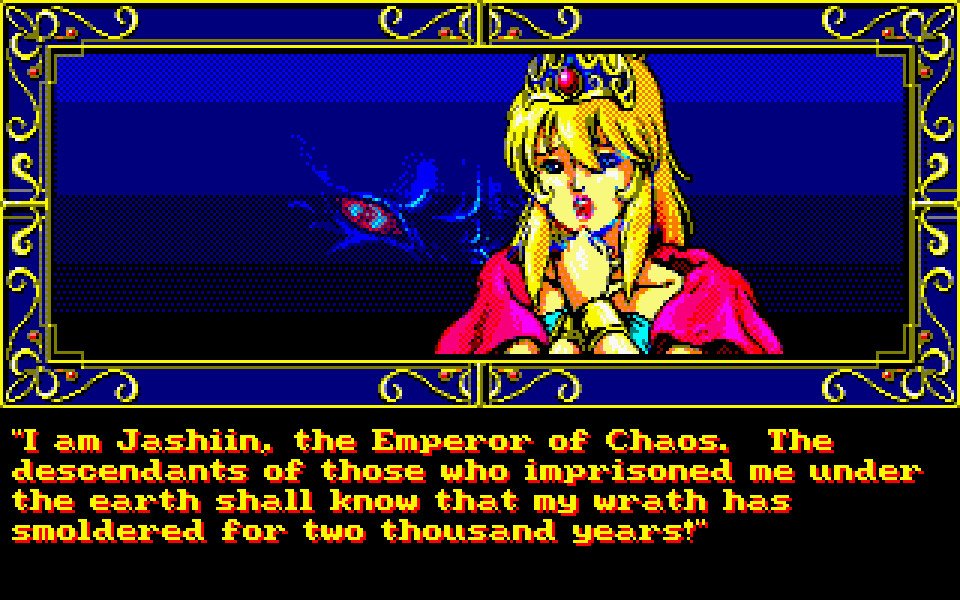

The game opens with an honestly breathtaking set of pixel-art cutscenes, with fade dissolves between really excellently made digital art that tell you the story of the kingdom of Zeliard, where a demon prince awakens, turns a princess to stone, then that kingdom’s king turns to Duke Garland, a duke, and sends him to quest to kill the demon king, recover gems that will retore the nation, and heal the princess.

And that’s it, that’s your plot.

It’s not a plot with a lot of depth to it, but to be fair it doesn’t promise it. You wander around town, you talk to traders, you can buy swords and shields and potions and magic and can find in the dungeons you fight through, other towns that have other things to buy and sell. It’s also got a lot of those hallmarks of difficulty that even in my childhood, I could tell were connected somehow to a different mindset of games. If you die, you get warped back to the last place you saved and you lose everything on the way, and you even have your broken gear lost as well. The first area’s first monsters will just straight up kill you if you don’t time your attacks right, and there’s no ‘easy’ places to stand still.

Turns out that this game was made easier for American consumers than the original Japanese game, which had even more precise timing, even more endurance-based play experiences. There’s a host of things I enjoy in a game, like there’s a magic system, there’s items you get to equip that make moving through earlier levels easier, there’s some backtracking to find things in earlier towns you didn’t need until you get to a later bit – it’s a formula I wouldn’t recognise until a lot later that we commonly call a ‘metroidvania.’

The first version of this game released in 1987, a year after the game Metroid released on the Famicom Disk system.

I don’t normally like to use this many images for a game pile article. It’s not that there’s anything with image density, I just feel that lots of images feels like you’re not getting value out of my writing, you know, the thing I think you’re here for.

But with Zeliard I was honestly considering making a video of it, just so I could show you how good this game looks. This game came out on the PC in 1991, sold by Sierra software, and it sat on shelves alongside games like Duke Nukem and Dark Ages, platformers which were much more linear and looked a lot worse. Now, this isn’t to shame those other games, but rather to try and put in context for you what it was like to see this game in that space.

Zeliard was a game that occupied literally years of my life as a child; I would play it after school trying to find the next path forwards, trying to improve at the game, bit by bit, until I was good enough to buy the pieces I thought would make me able to handle the next step of the game, then pushing those advantages little by little too. I literally started to run up debt in this game – hitting points where I was spending more money on repairs than I was making in my explorations in the dungeons.

I never finished it.

I never finished Zeliard, and moved on to other games. I thought, perhaps, now, as a grown adult, I could go back and try it out, see what I knew now and how managing these large maps would work with an adult’s brain and not a child’s.

And y’know what?

Zeliard kicked my ass all over again.

I didn’t make a video about Zeliard because I can’t get three levels deep in this game. I am not good enough at this game to make meaningful progress showing you this wonderful pixel-art dungeon explorer.

If you’re into the genre, I definitely recommend you go and acquire the game as a type of abandonware. I found it interesting, I enjoyed its low complexities, and even now I’m still wowed by how good it looks when it does things like facial animation with the limited tools it has.

1 Trackback