You know what Wolfenstein 3D is. Probably. if you don’t, here’s your basic rundown.

Wolfenstein 3D is a classic first-person shooter game that was both pretty good and thanks to shareware, widely distributed. One of the games made by id Software, as part of their arc of changing the face of PC gaming, Wolfenstein 3D was a spiritual successor to an old stealth game on the Apple II and other platforms, Castle Wolfenstein. The game started with you trapped in a dungeon full of nazis, with a limited toolset to escape that was, basically, killing nazis.

There, okay, we all done with the basics? Don’t need me explaining graph paper and stuff? Cool. Moving on!

I’ve been watching a lot of speedruns for old shareware games. Thanks to CapnClever, a speedrunner who focuses on that particular era of DOS games, I’ve been enjoying the spectacle of watching games that were designed to soak up weeks of time and leave you thirsty for more being blitzed through in a matter of a few minutes. Sometimes, glitch performances make games faster, but most of these games were surprisingly glitch-light.

This period of time was a sweet spot for games, where you weren’t pushing the system super hard, and therefore there was less need to do ‘cute’ things with the processor. You were mostly trying to push storage capacities – you had to fit your entire game on a 3.5 inch floppy, and with only 1-ish meg of space to work with, and not even a guarantee the game would get put on a hard drive, you wanted to make sure that your game’s content could fit. Games tended to be about a small amount of content, iterated on multiple times.

You can do a little many times, though, and when you have animations and textures worked out as making the bulk of your content, your levels can become basically tiny text files with markers on it for things to be spawned in. Even the more complicated levels of Commander Keen could be stored as a .pcx file with a few spawn points on it, because backgrounds were so simple. The games don’t tend to be glitchy, because they don’t tend to try and do lots of things, instead choosing to feature lots of stuff.

With that taken into account, then, why are Wolfenstein Speedruns So Fast?

You can finish Wolfenstein 3D in 30 minutes, in a speedrun and that’s not even pushing it. Hell, the game itself comes with par times that gives levels times like 3:30, but right now that’s more than the record time for several episodes of the game. An episode is nine levels – some of these things are getting finished in 23 seconds! How is it possible that these games are designed around this sort of molasses-thick idea of ‘fast’ when ‘fast’ is so much faster?

By the way, thanks to opening that question, while I’m at it, I kind of want to point out how funny it is that the design of Wolfenstein 3D assumes that a handgun, a machine gun and a chaingun can all be fed with the same ammunition. It’s funny to me how that stands out as silly. I actually noticed this while watching Blake Stone runs, because in Blake Stone the guns being all fed by the same energy cells makes some kind of sense, because it’s deliberately unreal. This isn’t worth a whole point unto itself, but it still struck me as an example of theme versus mechanic.

Anyway part of why Wolfenstein 3d speedruns are so fast is a piece of undiscovered functional technology. The game interprets mouse input as an absolute indicator of speed – if you mouse up fast, the game interprets that movement as much faster than what it’ll let you get with your basic input. Fine. That can definitely improve your speed in the game. Also, 100% consistant speeds thanks to processors and hard drives that are now thousands of times faster than the hardware Wolfenstein was made to run on definitely makes loading time faster.

Yet, even then, there are other games of the same era which aren’t so swiftly run. Games like Duke Nukem and Cosmo’s Cosmic Adventure still have some stuff to get through, and I think I’ve hit on why. It’s that those games resist you through required actions, but the main way Wolfenstein resists you is through uncertainty. That uncertainty is part of all the id Software work, of course. Commander Keen games are mostly made up of unnecessary levels – Commander Keen 1 only needs something like seven levels out of something like twenty, Commander Keen 2 is almost nothing but the essential levels, and Commander Keen 3 features something like only three essential levels out of the whole game. Your main challenge beating Commander Keen as a series is going to be not so much completing all the levels as finding the levels you have to complete. In Keen though, you can view other levels as ways to make you more capable of handling the levels you need – picking up more rayguns and lives (through points).

Wolfenstein differs from this in two big ways. One is that Wolfenstein doesn’t let you avoid levels. The other is that Wolfenstein levels are almost all limited in the same ways.

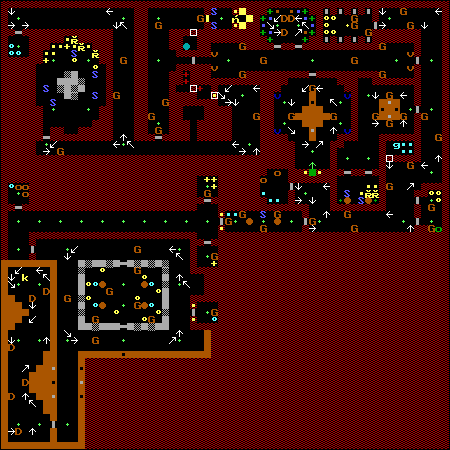

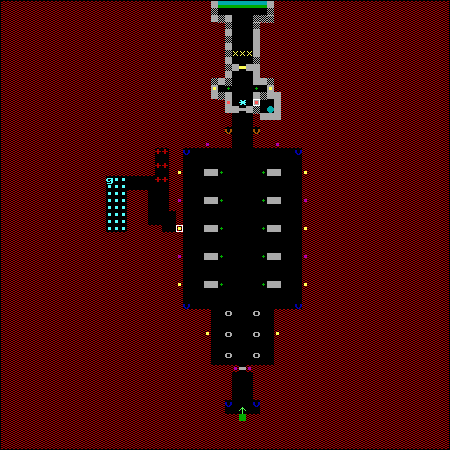

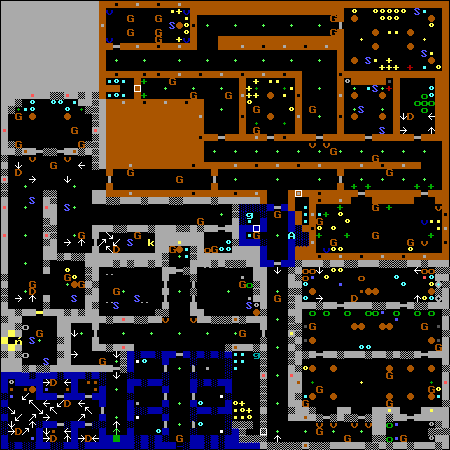

The thing that’s interesting is that for the most part, most maps aren’t actually terribly complex. I mean, look at them! There’s a limit for how big they can be, and the only real thing you can do with the grid design is some sort of a maze. Open areas make for more fun gunplay, so you want to include those, but the weapons are also primarily hitscan, so you can’t make the areas too big with too many people in them or you just get wiped out easily. You can’t do tight corners – or rather, you can only do tight corners, so there’s nothing remarkable in doing them. What this means is the big thing that keeps Wolfenstein in your way, what makes this game oppose you, is a resistance against the unknown.

You don’t know how many bullets you need, and you don’t know how many you’ll get to use. You don’t know how much damage you’ll take, and you don’t know how much damage you’ll need to do, and you don’t know how you’re going to recover. You have very small limits on everything – you have four guns, a hundred health, and ninety nine bullets, and these things come at you in increments of numbers like nine and twenty.

Now, I’ve said since that Doom is a game where: the fundamental puzzle of every Doom level is one where the level presents you with limited resources and then presents you with ways to spend as little of them as possible. That lesson is something you can get out of the variety of Doom – both variety in spaces and their shapes, and the enemy types, and the weapon types. It’s a really interesting example of how quantity creates a quality unto itself.

Wolfenstein has fewer parts, but way more levels. The first version of Doom had 27 levels, across 3 episodes. The first Wolfenstein had 60 levels. Now, the Doom levels were made with the experience of making Wolfenstein, and a lot of the vision of the future, but the options presented are really different. You can’t do timed effects or triggers (mostly) in Wolfenstein and you can’t really do stealth (though there is some vestigial elements in the system).

Yet, if you know your way through, if you know the kind of health you need, Wolfenstein 3D does very, very little to resist you. Beeline to keys, bolt to the exit, and you barely need to kill anyone, because most enemies aren’t designed to be good enough to hit you the first time they shoot.

Of course, there is the incentive system designed to reward you for being thorough – it rewards you for choosing to spend more time in each level, scouring them. All the levels can offer you, though, are a few types of point pickup, which yes, there’s a high score table, and you get the treasure because it’s treasure, but the way the game offers you rewards in the first level is the same as in the sixtieth.

This is the trick of Wolfenstein 3d. It is a game of information and courage. If you know, actually know how the maps are structured, if you know what’s coming, everything becomes so much easier. It isn’t like Doom’s emergence, where sometimes scenarios can get messy even though they’re constructed a particular way. Wolfenstein is a game that forces you to spend time in every one of its levels, with no idea how hard the next one is going to be.

That’s part of the mystery of it. You didn’t know when the game was going to introduce something new in a game that almost never introduced anything new.