You used to get a lot of game for nothing.

I think it’s hard to convey to people just how fantastically ridiculous the CD-Rom was to PC gaming when it first occured – games that were originally designed to be distributed in increments of four to six were suddenly being given over to increments of six hundred. Doom, in its original incarnation, lived on six floppy disks, and could be transported in the amount of data it takes to load the webpage of a single tweet. There were two ecosystems of technology at the time, and it wasn’t as simple as ‘more space means more big games.’

For a few years there, games were being made to try and exist in both technological spaces: the disk distributions, and the CD Rom distributions, with bulletin boards and early internet being more geared towards the former than the latter. You’d see illegal download websites proudly touting that they had ‘stripped’ versions of CD rom games, with all the audio and video removed, making the ‘game’ that remained something like twenty megabytes.

In the early days of the CD Rom, then, there were companies that – a little unscrupulously, really – collecting as many shareware or widely distributed titles as they possibly could, compiling them into 600 meg collections of games originally designed to fill 1 or 2 megabytes, sometimes with nothing but a text menu to show you hundreds of completely indistinguishable games from one another, and sell them to you. You could spend $15 and get a CD of shareware that, really, was ostensibly free to copy from someone, but then you’d have to find it.

That was part of the trick when it came to shareware CDs. They gave you a few hundred things to ‘play,’ but be honest, if it was on the third page of possible directories when you typed ‘dir /p’ then you probably weren’t going to go looking in that directory. They were garbage, the AOL Free Trial CD of the PC gamer set, with everyone having one or two of them and the task of looking through them being genuinely difficult.

Sometimes a bloodstained demon asks me why I seem to know all the DOS shareware garbage from this period, and I tell her, please, sheathe your blade when you ask questions like that, but also it’s because I had the free time as a church boy. That’s how I found all these shareware games, these free games, and the rare gem of a whole game that was somehow just being randomly pirated. Crystal Caves. Sam the Secret Agent.

One of those games – one of the good ones – was Traffic Department 2192, a project who had a 12 year old working as a composer and which presented as its shareware ‘chapter’ a range of about twenty levels and thousands upon thousands of words.

I learned from the best.

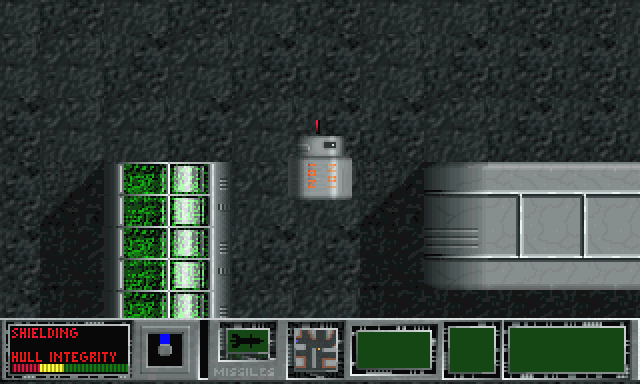

At its least sophisticated, Traffic Department 2192 is a top-down shooter where you pilot a skiddy little space-ship style vehicle around a city with surfaces you can bump into without causing any harm to your vessel, and then shoot at other vessels that are doing the same thing. Set (at first) on the desert planet Seche, in a city torn between a number of factions, it’s very much a game ahead of its time, in that it presents you with the same large map over and over, and sends you to waypoints around it, with just a point for the direction you should go in, and a mini map to guide you.

It’s not a bad gameplay loop either, where you go out, do some missiony-things of protecting a truck or blowing up a truck, hunting down a specific enemy ship or protecting another specific enemy ship and… that’s almost it. The game only has a few actual options for how you engage with the levels – go to a space, attack a thing, or chase down a thing, or pick up a thing. You’re not damaged by hitting the walls, and enemies are largely, pretty stupid, mostly hard to kill in that they move around seemingly at random.

There are three or four different kinds of ships you fly, and they are largely interchangeable – one or two of them are better than the others, but you never get to make any kind of choices about them. It’s just a way that levels vary one to another. The only difference between the Hornet and the Stiletto is just whether or not pressing the insert button does anything.

The gameplay itself is, well, fine.

It’s fine.

Look, when you get a game this long as a shareware game, you play it a lot, even if the gameplay isn’t particularly compelling. The thing is, if you go looking, you’re going to find that the people who remember this game really love it and remember it in many cases really fondly. This is the first time I’ve ever found fanlego for a thing before I found fanart. Why then, was this game so compelling? What made it so strangely sticky in the memory of a generation of eight year olds bored enough to search all the way to T on unguided archive dives of CD Roms that sold games by volume?

Well, the story.

And boy that story, it gets fucking dark.

This game was one of the first games I ever played with a content warning. The game opens with a screen warning you that the script has adult material in it, and you can choose to use an adult version of it, or a safe version. This right here was the kind of thing that blew my mind, because – because the game – it – it couldn’t check right.

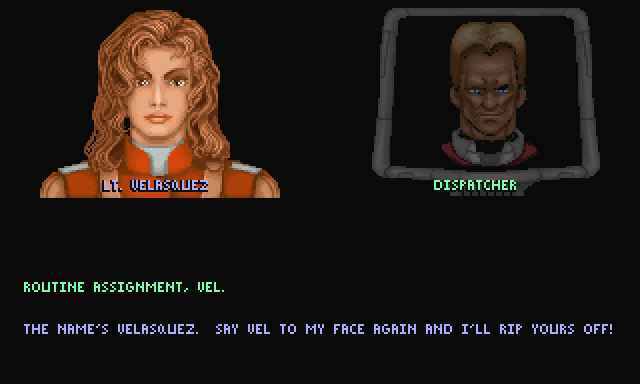

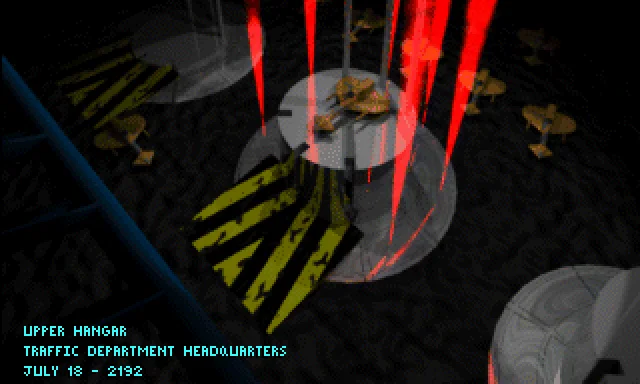

If I, a child, played this game, nobody was going to, like, get me in trouble. Right? Right? I played the shareware version of the game all the way through a few times, with the ‘safe’ script, reading and rereading it every time, as the story presented itself with the sort of cinematic direction we’d later come to think of as kinetic novel style. You’d get scene setting images, showing you the location you were in, then a black background with portraits appearing and disappearing to show who arrived and left, and the text direction took care of the rest.

The story then, follows our protagonist, Lt Marta Velasquez, a hot-shot traffic department skiff pilot with a chip on her shoulder, no desire to work with a partner, and a bad attitude, and what follows is the kind of sprawling preposterous storytelling epic you get when dealing with someone who doesn’t have an editor doing oversight, and can do almost endless quantities of script writing showing dialogue between two or three characters. The story shows you almost nothing, and instead presents you every kind of storytelling hook and scene you can get when the only way to present it is two characters talking.

Do you like Top Gun? Well, I hadn’t seen it when I saw this, so I didn’t realise that I was getting a crash course (ha ha) in Top Gun. Do you like evil clone stories? Do you like races against time? Moral dilemmas about cybernetics? Robot fucking? Dead partners? Cops on the edge? Cops that go bad? Cops that were always bad? Colony drops? Alien invasions? Resource struggles? Chief who’s sick of you stepping over the line, this time?

It’s what would sometimes be called ‘cliche storm’ but that is itself a cliche, so dang if I’m not a guilty party too. It’s just so bloody long, there’s so much stuff in this shareware game’s part one of four, and all of that stuff ramps up in the remaining chapters. It’s not a story that feels foreshadowed as much as the whole narrative was built a piece at a time in a single running first draft, like Grommit laying track out in front of the speeding train, and the simplicity of the whole thing means that the story winds up needing just more and more excuses to put up with the utter asshole villain you’re playing, Velasquez.

Oh, if you played the shareware game and thought ‘well, she gets better in the later chapters,’ I have some real bad news for you.

Vel starts out an awful asshole, and the closest she gets to not being an asshole is when she has a hole blown in her memory by Evil Enemy Brainwashing. That’s when they substitute in the story beat of her as a traumatised, wandering person struggling with phantom memories and the feeling that a chunk of her personality is missing because of something she can’t

quite

remember.

There’s some thematic stuff, like how Vel is clearly meant to represent that ‘my father was murdered’ creates a trauma that makes you into a total dick who murders people, which I’m not wild about, but it was the early 90s, and it was somehow trying to be a sci-fi epic and an edgy story about A Loose Cannon Cop, and everything else the writer put together at the same time.

This story was the byproduct of one Chris Perkins, who, despite my attempts to find out, may or may not be the D&D Chris Perkins, the guy who streams and has a fairly sizeable internet presence. While he’s famous in the context of tabletop RPG streamers these days, he’s apparently hard enough to contact that I can’t tell if he was the Chris Perkins that wrote Traffic Department 2192‘s enormous leviathan of a script.

The timing does line up – Traffic Department 2192 was made by a lot of younger programmers, as a sort of ‘early project’ to make videogames professionally. They made a bunch of games, games with names like Lines 2 and Highway Havoc (which was pretty good, but much less dense with wordswordswords), then all moved on with their lives to do other cool things.

Notably, one of the people involved in the game was a thirteen year old composer, who nowadays goes by the name Owen Pallett. Pallett was a trained violinist as a child and grew up to do more training and then he kind of didn’t seem to do much more training because he was releasing albums and getting awards and most notably recently, he was nominated for an Oscar for composing music for the Joaquin Phoenix x His Alexa vehicle, Her.

So there you go. Science fiction videogames, sometimes leads to Academy Award nominations.

EDIT, 2023: John Pallett emailed me with some additions here, and I’ve left my original text unedited above. But notably, Lines 2 and Highway Havoc were different people, and yes, this Chris Perkins is that Chris Perkins.

It’s available to play online, and you can go play it in your browser, even. It’s not a big game, but it was a really interesting one. Revisiting games like this can be a reminder that the early 90s were really a surreally different time, a time when it was absolutely not acceptable to not be better considering what was known and publically available, and how now, twenty-five years later, we’re struggling to try and catch up to where we should have been all along.

It’s also a game that shows something amazing about how it was made, about how tools shape the things they make, so a game which uses script and blank screens to tell story will have an enormous and overwhelming text dump of a story.

I wanted to make a video of this for this month, but this story works against that. The reason you pay attention to a game like this at all is its enormous corpus of written text, and while playing the game may take an interesting hour or so, a lot of that hour will be spent mashing the ‘next’ button.