Now this wasn’t something I expected; a really good limited-interface horror game.

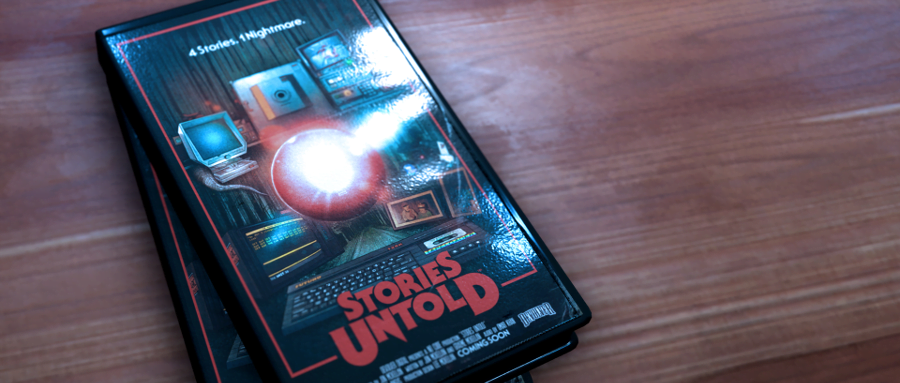

Stories Untold is a game that positions itself as firmly being about the 1980s, but about the technology of that era. It also relies on a creeping, uncomfortable sense of horror, a sense of unease that builds. You have to know that it’s going some place bad, but the knowing ahead of time doesn’t alleviate the tension, and the game does its best to put you under pressure by tugging your focus in multiple directions.

That said, this is a horror game, and it does deal with interface problems, feelings of isolation, confusion and memory checking across difficult, uncomfortable designs. I cannot remember anything I’d call a jump scare, but the game is definitely creepy, and there’s a point where lightning flashes and startles you.

If you want to experience the game in as pure a state as possible, and simply know whether or not I think it’s good or recommend it, then this is where you want to check out. The game is available at Humble, Good Old Games, and Steam, it is very good, and it is cheap enough that if you give it a shot and don’t like it, you’re not losing much.

Still here? Let’s talk about interface.

#fff, 1px -1px 0 #fff, -1px 1px 0 #fff, 1px 1px 0 #fff; -webkit-text-stroke: 1px white; padding: 30px;">The Physicality of Interface

Stories Untold is a game about technology and our interface with it. I don’t want to talk too in-depth about my opinion here, because I don’t want to tell you things that you’ll think when you play the game and replace your opinions with mine, but this is what I felt, what I came away with. The game recognises that technology is made up of physical objects, and those objects have tangible, real impacts.

When you play a game there’s this thing that your brain does called abnegation, where it stops seeing the boundary between yourself and the thing you’re working with. Good designs are seamless about this – hospital doors, for example, are designed so that people pass through them so easily that they can forget they even used one. When you turn your car, you don’t think that you turned a wheel to turn a gear to turn two wheels to turn the car, you think I turned right. The very nature of interface is to melt away and become invisible.

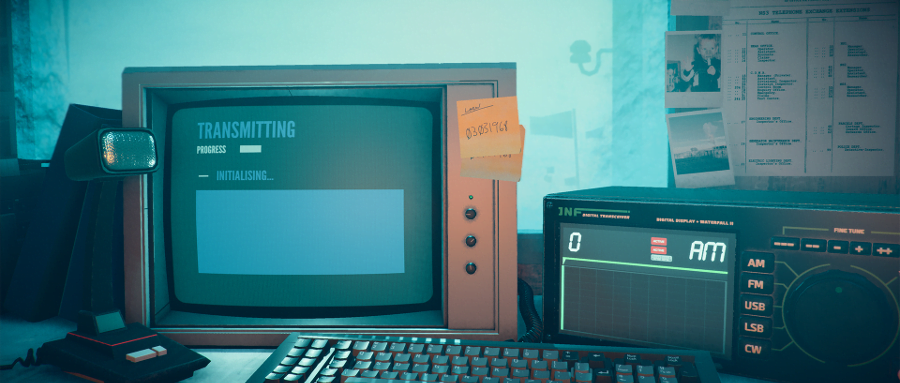

What Stories Untold does then, is use that invisibling effect to make the real interface (your mouse and keyboard) melt away, but also use the game’s presentation to make you feel as if you’re dealing with another interface. That interface is also, well, a bit crap. It’s full of chunky keyboards and glittering screens and CRT effects, it’s an interface that’s hard to melt into.

Horror in videogames is about balancing experience, about using means to generate tension without just telling the player to be scared. Videogames already are built around an encroaching failure – think about how many games have a death state that will happen if you don’t do anything, about how many games count down to an end. The play of Stories Untold is instead about putting success near you, but also making the passage of time very tangible, through the s l o w n e s s of the things you’re interacting with.

Stories Untold doesn’t want to force you to rummage for your keys as the killer lurches in on you. It instead wants you to anxiously wait for the next piece of information as a screen refreshes and you realise you made a typo and now you’ve lost more time.

#fff, 1px -1px 0 #fff, -1px 1px 0 #fff, 1px 1px 0 #fff; -webkit-text-stroke: 1px white; padding: 30px;">Narrowing Your Focus

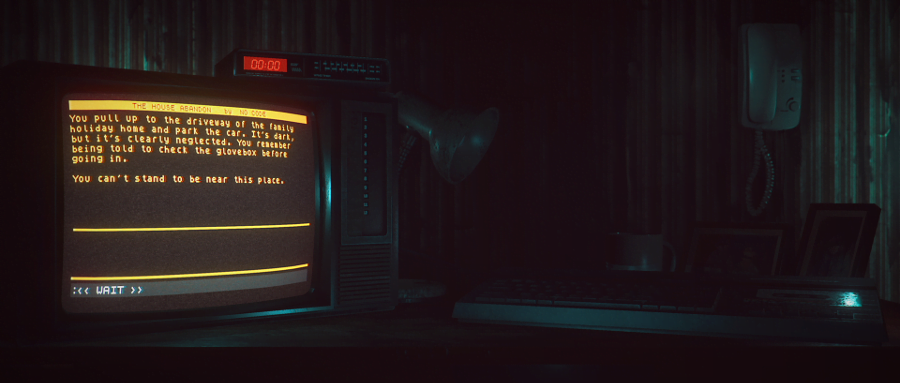

In a way, this game is about accessibility. It posits a modern day where our experience with interface design and design mindset was stuck in a period where being deliberately or unconsciously obtuse or thoughtless was fundamentally normal. Not because these things were trying to be annoying – I mean, I played a lot of infocom and sierra text adventures as a kid, and they’re a step of user interface evolved from the game represented in Story 1: The House Abandon.

It’s a clunky game which speaks to me of an interface it barely thought about – the best they could manage with the options they had, a parser that was probably folding itself double to just fit on a single tape – especially with that graphic in the opening, gosh.

I’m not a cinema guy. I’m at best an intrigued amateur. but in The House Abandon the game presents you with a screen, on which you, the player, will engage with a smaller screen. Maybe you’ll have headphones on. Maybe it’ll be dark and you’ll just use the light from the game. It’s certainly a place to start.

The game makes itself an experience of slowly dissolving away those layers of the interface as you play – then jerking them back when the thunder crashes, or the power goes out or when something else happens. It uses its framing cinematographically.

It also marvellously teaches you to focus on a small thing in a big field… so that big field can feature things sneaking up on you, environmental changes you don’t notice until after they’ve happened, and, in the other stories, to feel like this little window is your world. It makes an interface to make you forget your interface.

It’s excellent work.

#fff, 1px -1px 0 #fff, -1px 1px 0 #fff, 1px 1px 0 #fff; -webkit-text-stroke: 1px white; padding: 30px;">Putting The Pieces Together

There are four stories in Stories Untold, and in the classic anthology sense, none of them have much set up or conclusion. Really, if the game was just these three stories – even with the lack of conclusion, with the startling shocks you get, you’re still left with stories that construct horrifying, terrifying and creepy situations without you ever really needing to have those ultimate explanations of why things are the way they are.

One story is about an old text adventure game. One is a complicated medical analysis device with some gory visuals. One of them is decoding radio signals and old codebooks and number stations. All of them are marvelously atmospheric, thoughtful, scary and sad.

Then there’s a curve ball.

If you’ve not taken the theme so far, what you learn as you play Stories Untold expands what you may think of the game. While the game presents itself as four small stories, there is a narrative in the fourth story, a narrative that may not actually be necessary.

I’m not going to try and explain to you what the curve is; normally when a story does something like that I feel it’s necessary to do so, and usually, be mad at it. In this case, I don’t feel like it changes the existing pieces meaningfully, but it does excellently create a new narrative with the information you have.

It’s an interesting and I think a bit brave thing to even try. What stands out to me the most about it is that this conclusion story wields a lot of things I normally feel are awkward and hamfisted, and could mishandle. It could really heck things up.

It doesn’t.

It’s not my favourite story of them all; it’s not even, I think, the best of them. But it is interesting, and it is smart. If you find yourself wondering if there’s a reason to finish all the stories, well… that’s the one to try out. It’s pretty good. It highlights themes and it explains ideas and it even plays a bit with the interface thus far.

#fff, 1px -1px 0 #fff, -1px 1px 0 #fff, 1px 1px 0 #fff; -webkit-text-stroke: 1px white; padding: 30px;">Verdict

Still, content warning for medical horror, mechanical horror, alcohol abuse, and flash scares.

You can get Stories Untold at Humble, Good Old Games, and Steam.

Verdict

Get it if:

- You want something small, thoughtful and interesting

- You like old technology

- You want a good way to consider user interface as it relates to players

Avoid it if:

- You’re very impatient or easily frustrated

- You don’t like codebooks or deciphering systems

- You have a hard time tracking memory between sequences