How much can you get out of how little?

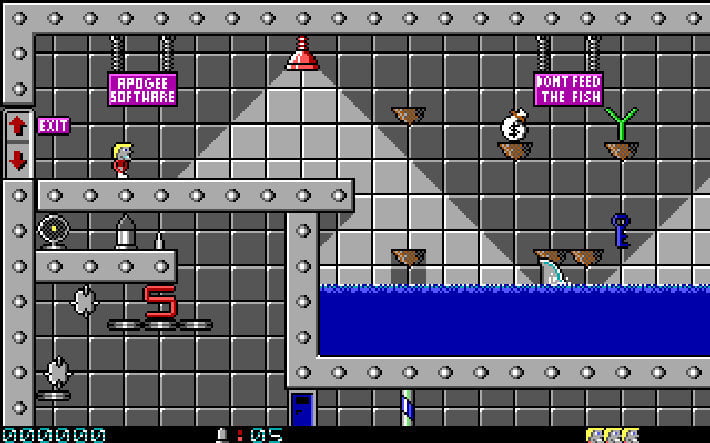

Sam the Secret Agent was an Apogee shareware game from 1992, made for systems that had what we called an EGA palette – standing for Enhanced Graphics Adaptor, which could display sixteen colours at once. This was enhanced in comparison to the CGA palette, or Colour Graphics Adaptor – a format that could show four colours at once. I bring this up because at the time when consoles were already getting into a war over graphics at high speed, the PC was struggling with an interface and data storage options that promised more depth, but delivered so little by comparison.

Secret Agent casts you as Agent 006½, and just

Let’s stop right there.

The idea behind Secret Agent is that it’s a platformer videogame that draws on the well of tropes of stuff like your James Bond style stories. I say ‘draws on’ because when you look at what the game is trying to do, it doesn’t feel very spy-ish? Not really? Your character is a little squareish sprite that can jump four times his height off the ground – which isn’t a problem for videogames, but when you play through it, you’ll find yourself wondering about how many classic secret agent tropes just don’t show up – and how the levels you’re navigating are largely just random collections of rooms with nothing particularly spy-ish to do in them.

It’s not a stealth game – there’s no way to hide or avoid things, and your opposition is made up of a number of robots and machines and gun turrets that shoot blimming full size missiles. You can view the destruction of radar dishes and the deactivation of security barriers as kinda spy-ish, but it’s a rare thing in a game like this.

Basically, the only secret agenty thing that you do in this game is run around on an island killing lots of people without remorse.

What makes Secret Agent to me is how much this little shareware DOS game from the early 90s stands as an example of what Marshall McLuahn implies with The medium is the message. See, this game is the second game made using its engine – the engine first employed by the much better and much more fitting game Crystal Caves. In that game, you’re a space explorer looking for shiny rocks to finance a twibble pet farm (yes), with a tongue jammed in your cheek. The enemies of that game are weird alien life forms from an unexplored planet, and the game is full of inadequate infrastructure, and you get to levels by exploring a large map that is, itself, a big mine with supports and struts. It’s not the prettiest EGA game in the world (that would be Loom), but it’s still a game where the engine of the game works to let you do the kind of things that game is trying to do.

Secret Agent feels like a game that was made with the Crystal Caves engine, but which also had no time or energy to make additions to it. It feels and plays like a straight port, complete with enemies that transform when they’re attacked. In Crystal Caves, these enemies transform because they’re fruity weird alien monsters – in Secret Agent, they’re meant to be actual flipping humans, and show a progression through the natural forms of human – thug in leather jacket, blue armoured ninja, black ninja with nunchuck, slow moving red person, white person with a knife, and then a massive headstone. Or there’s the way that to escape levels, Sam has to find a stack of TNT and blow up the door, every time! That sure looks like a mechanic created for a game about mines.

Now, obviously the response to that is ‘it’s a videogame,’ but yes, this is a videogame that chose to call itself Secret Agent and name the main character after a number very close to James Bond’s. There was a deliberate decision to try and work with an aesthetic like this, and to make the game feature ‘parody’ references to different spy movies.

Yet, when the impetus was to make a game that felt like a spy story, the mechanics they had to work with were shaped by the engine that was used, an engine that did not have room for hacking doors or sneaking past guards, but did have room for a spy that could leap four times his height off the ground.

It’s a fine game. It’s unremarkable. It’s a shareware game, with one chapter distributed for free, and two more you have to pay for and shouldn’t bother. Now, don’t let me seem down on the idea of reusing an engine, let me be clear: this is a great idea, and people should be using every tool they can to make the games they want.

What’s a bummer about Secret Agent is how little of the new ideas could be expressed in the game itself.

1 Trackback