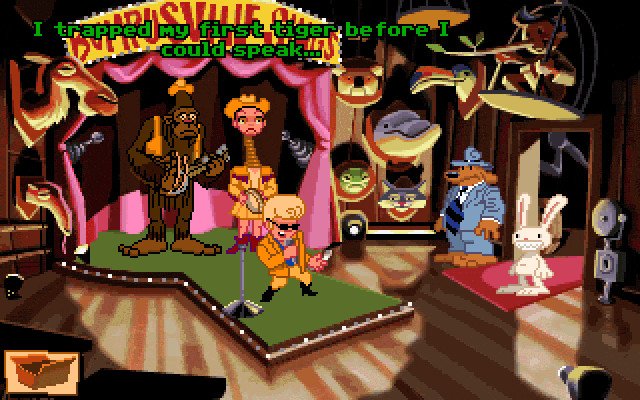

Okay, so straight up, Sam and Max Hit The Road is one of my favourite games. It’s a point-and-click adventure game with some frustratingly obtuse puzzles. I don’t know if I can even recommend it as a game per se because the times I struggled with the solutions to its ridiculously obtuse view of the world are all so far in the past that I can’t imagine how anyone would solve them. Some of the puzzle solutions are positively arcane.

When you boil down a lot of point-and-click adventure games, they have one problem: Use key on door. In fact, sometimes games that tried to do something different (like Future War and Full Throttle) were criticised for the involvement of those other elements. In Sam and Max Hit The Road, there’s a handful of, y’know, bits and stuff designed to introduce other puzzles and problems, but none of the game is too hard once you grasp the thread of the game’s weird poke-it-and-see methodology.

So, right, as a game: It’s good, but it’s of its time. The GOG release brings automatic saves and windowed play and those are nice modern conveniences. Okay? Play it with a walkthrough nearby but don’t follow the walkthrough directly. Just use it when you’ve poked everything to laugh at the responses you find, but not to remain stranded in a narrative point for a while. I like it, I think it’s good, it’s cheap and it’s really funny.

And hey.

Now.

Let’s do the heck out of talking about Sam and Max Hit The Road.

Culture

Sam and Max Hit the Road is a game that really couldn’t be made today, and we know that because when Sam and Max got episodic content that content worked more or less at odds with the way the game felt, but more about that later when I talk about the sequels. Everything in the game had going for it was one of those lightning-in-a-bottle moments for its genre, for the gaming culture, and even for the company that made it.

It was made by Lucasarts, the only people who could comfortably make fun of Star Wars in the gaming sphere, who had access to some top-notch graphic assets (in the form of artists) and an engine that they knew inside and out. What’s more, that engine was really good at this one specific type of game and didn’t try to get weird or cute with it. They had the tools and the skills and the people and they had an idea for an intellectual property that was very much being built on the creative mind and work of one of the people working on the game rather than chasing a marketable franchise. Basicaly, Lucasarts had enough money and clout to make something nobody cared about before they started, and made it excellently enough that it endures even now some twenty-three years on.

While games like Day of the Tentacle and Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis sought to represent a location or a single movie’s adventure narrative, Sam and Max Hit The Road wanted to make its whole story about a ridiculous road trip across an enormous country and show a resting state of considerable, constant weirdness. This meant that the game was about showing off a culture, and that meant that most of the game, for all that it’s about following an interruption to the status quo, is about representing a status quo that somehow all fits together – a default state. And that means you can look at Sam and Max as a little time capsule of the childhoods of the people who made it reflecting on the America they knew released into an America that was.

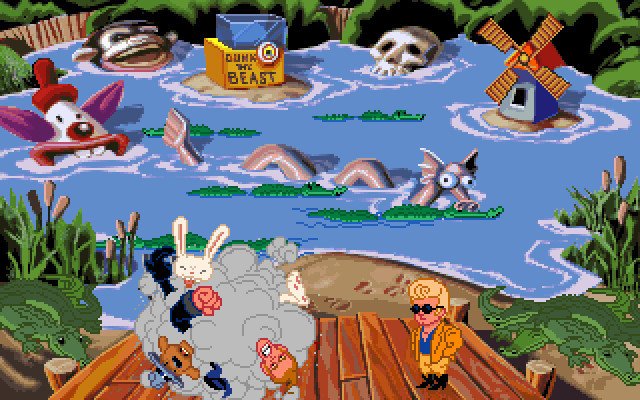

Sam and Max represents a world that is pre-cellphone. It’s 1994. There are phone booths – and one factors into a puzzle. It’s pre-internet, too, and the world it depicts is the Weird America of that pre-internet life. If you journey across Sam and Max’s America, you’ll be treated to a series of roadside weirdnesses. Their starting point, a office in the big city, is crime-riddled and surrounded by degeneracy. There are gunfights at random, a store selling GUNS, LIQUOR, BABY NEEDS (which still makes me laugh) is on the corner, and violence ensues at almost all opportunities.

It’s when they’re pulled out of this needless depiction of 1990s inner-city crime and poverty that they streak across the country looking at this compulsively weird culture, and that culture is something that’s sort of faded. It’s a given in Sam and Max that there are UFOs and Bigfoots and roadside attractions with strange dark fates to them and tourist traps that are themselves, actually real things. There’s Jesse James’ severed hand in a jar and it’s just, y’know, there, in a carnival. There’s even a puzzle about finding a location on the map that lies between other, extremely ludicrous magical locations.

It’s this particular view of America’s middles and betweens as being populated by the unnatural simply forgotten by the cities that has faded in recent years. The era of the cellphone and the universal camera means that a lot of the things that Sam and Max jokes about existing are kind of past beliefs, with new, much more dark and hateful conspiracy theories replacing them.

There’s something childish about it, too. There’s something lovely about how you play with paper cutout dolls, or a diner placemat map, or that you can play Travel Carbomb (and that’s a name that aged poorly, fast). It’s a game that remembers being on these journeys as a passenger.

Values

There’s a lot of subversion in the oddness here as well. There are some locations that are literally interchangeable with one another – functionally identical spaces but for some minor, superficial changes. The Snuckeys are all the exact same locations, with the exact same key items and dialogue and puzzle solutions, a little subtle poke at the very nature of American tourist trap franchising.

Yet at the same time, this little corner of capitalist culture features a little glimpse of one of the other values that runs throughout Sam and Max Hit The Road: Happiness.

Whenever you meet people, broadly speaking they are doing okay. The story represents a whole range of people across the United States, mostly people who are working in touristed areas, doing menial jobs or thankless tasks… and they’re okay.

Most people aren’t happy, not wildly so, but they’re okay. There’s the Snuckeys employees, who are all identical and talk about having to comply with the brand’s standards, but they’re okay. They take pride in their work. They enjoy things in their work. There’s a man whose business flooded and he devised a solution. There’s food servers and store owners, there are tourists and hobbyists and yes, some bigfoots and people solving their day-to-day problems with rebranding efforts, and mostly, people are okay living their lives in their weird ways. There’s no apocalyptic sadness or unhappiness – there’s a certain joy for all these people who are just enjoying what they enjoy, doing what they do.

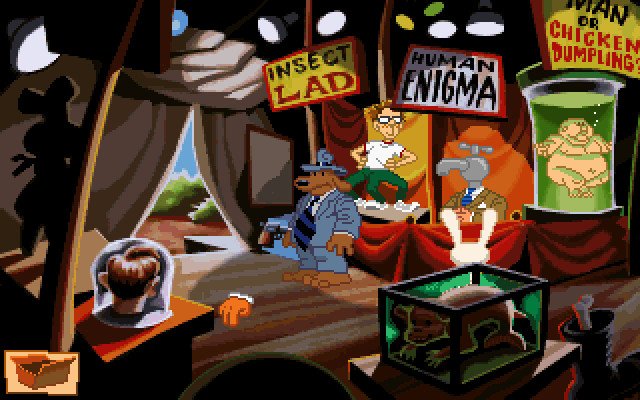

The thing that’s really interesting to me is the story only really represents a small number of people as being unhappy. In fact, specifically, there’s only one major character who both starts and ends the game unhappy, and that’s Conroy Bumpus, who is also depicted as being vain, self-obsessed, cruel and rich. Conroy built a monument to himself in his ranch and he spends much of the game disappointed and unhappy because he can’t have what he wants – a non-human humanoid to torture. The one other probably-wealthy person you see in the game is Evelynn Moriss, who is depicted as being a bit spacey but also using her wealth and position to benefit the bigfoots – who are her guests.

Narrative

Hell, let’s talk about story structure because, inexplicably, Sam and Max Hit the Road has a good one. I’ve spoken about how good stories that want to feel rooted to the real world are ones where there’s a single instigating event, like in Stranger Things. There’s a single instigatory event in the narrative, but without that instigating event, the other things in the story exist and would have existed in a sort of stasis. The Bigfoot party was going to happen whether or not Bruno showed up; Conroy Bumpus was always fooling around looking for a Bigfoot to add to his collection; and Sam and Max weren’t even going to do anything different with their day unless the instigatory event happened.

That event is Trixie, the Giraffe-necked girl, conscripting the Fire-breather to free Bruno, with whom she’d believed she was in love. Trixie is a lot of things (it’s kind of weird she’s white but I’m also super relieved she isn’t black), and her story is silly, but she’s still someone who wanted something, made a plan, and took action to make it happen. It’s kind of hard to hold her up too high because she is ultimately a silly character in a silly story where almost every character you encounter is an incompetent boob, but she’s not worse than anyone else?

That’s another thing, too! Hit The Road has like, women in it? After replaying Space Quest games it’s kind of dizzying to realise that Sam and Max, with its four women with speaking roles, is a lot better about women than some other games of its era. Because holy hell that’s so depressing. FIVE! And none of them suffer anything randomly terrible – though I suppose Trixie does get kidnapped at one point, which sucks. There’s also a woman in the introduction who is herself not a character, but does exist to show up the awfulness of the self-styled Nice Guy archetype.

Still, in this era of Oh Yeah Women Exist?? it’s amazing to see this game treats them in a way that’s Definitely Not Good Enough, but still is so much better than many of its peers. It has a better plot and better character representation than many games of its generation – and this is a game where you play a talking dog who’s friends with a lagamorph!

Verdict

You can get Sam And Max Hit The Road on GOG, and that’s all for now.

Verdict

Get it if:

- You already own it in some other format

- You know you like point-and-click games and want a large one

- You want a game that’s funny and want to marinate in it

Avoid it if:

- You’re looking for a game that’s mature in its problem solving

- You’re really not into the use-thing-on-thing school of problem solving

- You want all your puzzles to be very key-on-door solutions