For anyone who doesn’t already know the vital statistics, Portal 2 is a first-person perspective puzzle game, the sequel to Portal, that was released in 2011, by People Valve Software Pays. Saying Valve Software made it is possibly overstating the role Valve Software, the organisation, has in things Valve does.

The game is centered around a non-speaking protagnist with a special tool that lets you create portals between two locations. It does this at range, so we call it a gun, because our brains and reference pool is pretty weird. These portals let you connect two points in space – and so much of the rest of the game is just built on exploring that idea. Puzzles become about how much freedom of movement you can get by folding two bits of reality together. It’s also fun because the human brain really isn’t built to deal with that kind of perceptual shift – it’s literally something our brains resist doing.

Filling in the rest of the space of the game is an evil AI that’s literally running you through the puzzles, as tests of your mental acumen, and the helpful AI that’s trying to keep you alive so you can escape. You’re followed not by bodies but by voices – old audio logs of a long-lost inventer, and the responses of your two AI companions. The game is stark and empty, but uses that emptiness to fill it with a dilapidated ending, and the story you get is made up of two fascinating parts: it tells you what came before the last story, and what comes after.

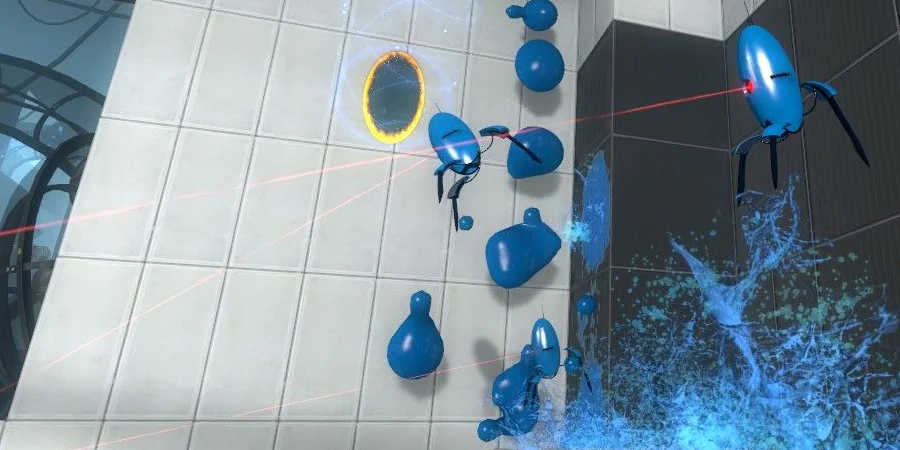

Taken as its own entity, Portal 2 is an enormous game, with a single-player campaign that’s very good, then a cooperative campaign that’s pretty good, and then an absolute massive amount of DLC and fan-made levels that range from pretty good to oh well. It’s a lot like Little Big Planet, where there’s some tailored content that sets a very high bar, and then a huge swell of player-driven content that tries to meet it.

You can get Portal 2 on Steam, and statistically, if you’re reading this, you probably already have it.

Portal 2 is a thoughtful, puzzling, incredibly funny game which holds itself together mostly through a coherent vision of its own identity. Puzzle games tend to have one of the hardest fictions to construct – when you want to make puzzles reasonable, like they’re things that exist in a universe, around the player, then you often wind up with spaces like the infamous point-and-click adventure, games like Full Throttle and Day of the Tentacle and Sam and Max Hit The Road, which are great, or you wind up with something like Space Quest or King’s Quest, which aren’t, um, great.

Now, there’s a limited mine for stories about being trapped in a sadistic puzzlebox by some jerk. If nothing else, the range of copycat stories that really want to be More Portal that have come since then show that you kind of don’t have that much you can do that’s totally new.

Not that only Portal 2 can do a laboratory-trapped plot, but that Portal 2‘s laboratory-trapped plot is really good, which means any other examples of the work invite some kind of comparison. Consider A Story About My Uncle works with some of the similar space, but it uses its science plot hook to pull you into a much larger world.

It’d be entirely forgiveable if Portal 2 built its plot around just the conflicting AI, used all the portal puzzles it could, then moved on. Instead, it adds to it a bunch of backstory (which isn’t strictly speaking necessarily), which is mostly the result of hearing JK Simmons being an absolutely unreasonable thunderous super-science dumbass. There’s an undercurrent of the world in Portal 2 that super-science is not the byproduct of some sort of superior intellect, it’s really much more about ridiculous people who had enough money to keep rolling the dice.

There’s a subtle understory too – Cave Johnson didn’t succeed – he kept failing, he kept getting people killed, and the end results of some of his work was literally catastrophic. Yet, despite the constant failure, his company had enough money, and enough investment to keep trying. And when you’ve built the vast underground laboratory, it’s cheaper to make the experiments in them. It’s very possible to read Portal 2 as a story about the myth of the capitalist industrialist. Cave Johnson doesn’t have to be good at anything, and he can in fact fail endlessly for years.

I mean, it’s probably not, it’s probably just that super science being made by ridiculous people is funny.

The reason I wanted to write about Portal 2, though, is because I’ve been thinking a lot about Want You Gone, the song that plays over the credits. Portal had a pretty clever structure of a short puzzle game with a funny finale and a catchy song that rolled over the credits, which became kind of so common in a particular genre that there was even a fairly well-distributed parody game. In Portal 2 we got more of that – a bigger game, more plot, more backstory, lore, and finally, the finale song, Want You Gone.

Want You Gone is excellent. I like it a great deal more than I like Still Alive, which is a great song as well but ultimately suffers from being a bit more openly memed. Still Alive is a song that can be removed from its context and tells its own science fiction story – you really don’t need to know how Portal goes to understand the story toldin Still Alive. Want You Gone is, on the other hand, more a necessary part of the media it’s from.

Now, this does mean that speaking conventionally, I’d definitely say Still Alive is the better, more tightly crafted song. Which stands to reason – it’s harder to create in a small space! And yet, I do prefer Want You Gone more, because it’s part of the whole work. It’s a better song for being part of the game than Still Alive, which is a better song.

The thing with this song though, is that it stood apart because it’s so odd. It wasn’t the kind of song you were hearing on videogame soundtracks, because largely, videogame soundtracks were being made by people who made videogame soundtracks, and people who wanted to maximise the impact of existing videogame soundtracks. Those soundtracks definitely wanted to borrow from existing genre stuff.

Erin Mclain, the voice of GLaDOS, is an opera singer. And that’s not just her part-time job, back in the 90s, that’s what she used to do as her job. The fact that she became part of the Valve voice acting soundscape and therefore got roles as a Calming Creepy Computer Voice is as a result of her training, which as an opera singer included the breath control that means she’s never breathing mid-line – and that’s part of why GLaDOS sounds so very inhuman.

I wanted to provide an example here, but thanks to The Internet being The Internet, now it’s basically impossible to find video of her doing anything but singing something Valve-related, which is super annoying because she’s an opera singer. Her skillset is much broader than videogame songs. There is more than just our culture here.

Portal 2 is a game cursed in part by being a sequel to Portal. If Portal hadn’t been so close to a perfect unit of gameness, and yet at the same time, so engaging and funny that it was easily run into the ground, if it hadn’t been so influential, we wouldn’t have any reason to be sick of The Cake Is A Lie, or games that tried to ape the structure of a Whacky And Unhelpful Science Laboratory Helper versus Our Hero.

Time to time when I sit down with my students to talk about games they can make, when I want to talk to them about media they could make, I start by asking them what’s something you like. What’s something you care about, what’s your thing. And I ask that because, almost always, there’s something interesting that your interests bring to the media making.

Part of what makes Portal 2‘s voice so excellent is that the woman who voices her brings an otherwise rarely-seen skillset to the game. That gave the AI her voice, and that voice invigorates the AI, which in turn encouraged the writers to do more with GLaDOS and that made the game even better, overall.

Build around your thing. It’s okay. You might make something awesome that nobody else could have made.