Spoiler Warning, if you think you need it. I will discuss things that happen in the opening few minutes of gameplay, after all. Also content warning for the things in the Life is Strange trailer – death, abuse, gun violence, endangerment, that stuff.

I’ve had a lot to say about Life is Strange.

Life is Strange was, for its time, more than just a videogame. It was a conversation. For games journalism, Life is Strange is one of those beautiful excuses to talk about almost anything you want. Life is Strange is a deep text – you can examine it as a queer text, a feminist text, as a failure of either, you can do hostile readings of it and you can do autoethnographic readings of it. You can do what I did, and invoke intertexuality, where I considered the game in light of other titles, like Mass Effect 3 or Bioshock Infinite or Dontnods’ other game at the time, Remember Me.

By what it chooses to be about, and the way it tries to shape its experience, Life Is Strange has depth as a text. There is not nothing there. As you engage with the puzzle of what the game means, or what it is about, it resists you. Bear in mind, though, there is a difference between having depth as a story and having depth as a narrative. It’s not a product of quality of the game that means we can spend so much time talking about it – if anything, it’s that Life is Strange aspires to be complex and yet is so basic.

You can talk about it as a model, you can talk about it as an aspiration, and you can definitely talk about it as a failure.

Still, Life is Strange is definitely important, and it’s been root for a wealth of important writing. One piece of writing that Life is Strange created, though, is this game:

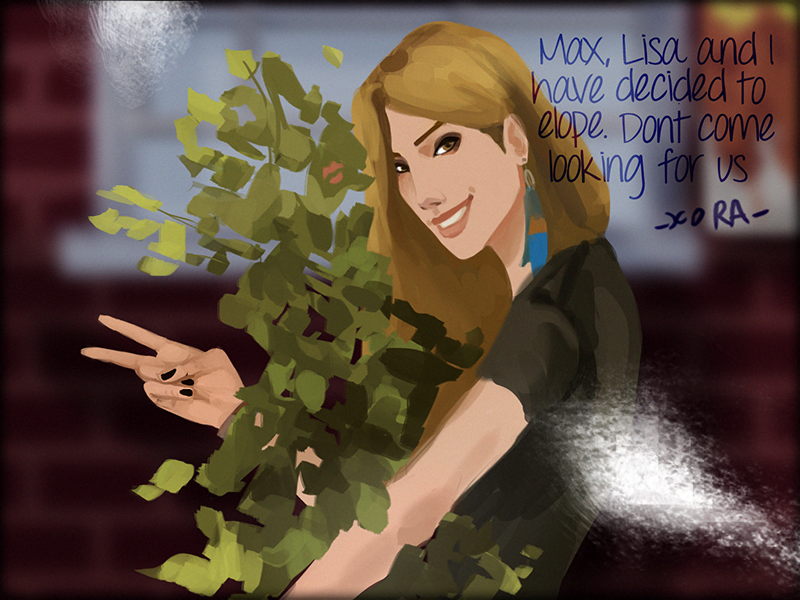

Love is Strange.

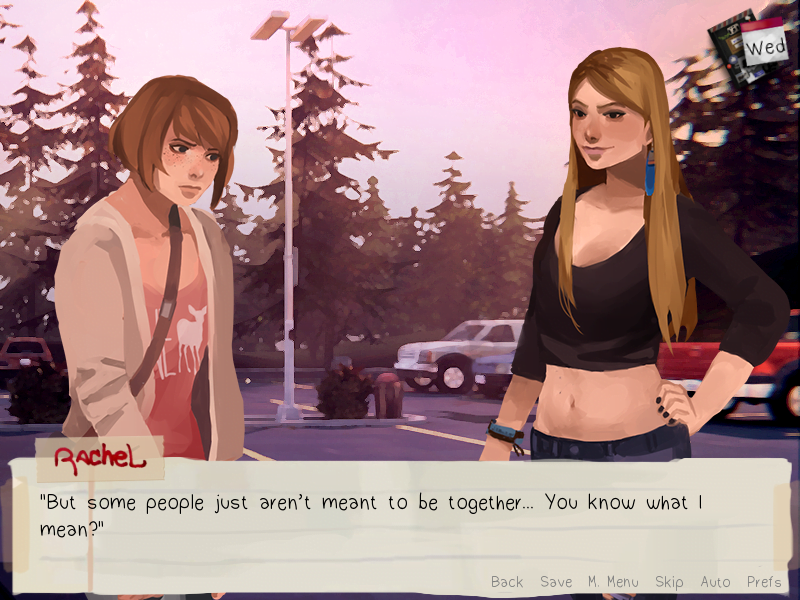

Love is Strange is a 2016 visual novel, created by Rumblebee Studios, and it’s available on itch.io. It shows you an alternative universe version of Life is Strange that doesn’t feature time travel or serial killers or contrived apocalyptica. It’s a game where you play Max Caulfield, a normal young woman who goes to school with Chloe Price, Rachel Amber, Kate Marsh and Victoria Chase, and how she winds up dating one of them.

Love is Strange is a short, easy game to play, I enjoyed it, and I recommend you give it a shot. There’s no real representation of dudes in this game, but that’s fine, the game is very nicely clear about what it’s about. This is a game where a cute girl tries to date some of a number of other cute girls.

I think this game is really lovely – it’s sweet, it fits in the style of the original Life is Strange, the music is nice, and the challenges of the plot as presented are very clearly about connecting with the characters. There’s no dreadful puzzle to the game, not really, but there’s still a lot of lovely graphics and multiple endings to pursue. You can lean into the way a character is, or try and guide them towards Max’s way of doing things, but whatever you do choose, it’s a game that puts its importance on the emotions of the people involved. You don’t hunt down bottles or try to tediously navigate a conversation maze with a rewind power to save you.

This is fan work. The game is 100% free, and must be, because it’s a game about another game, using characters in the same way that fanart does. Because I’m paranoid about this, I’d like to recommend you take the opportunity to go download the game, if you can, and thank the creators for their work. I guess that’s your giveaway – I think this game is really good.

Go download it, and play it, and have fun with it. If you don’t like it, it cost you nothing and you can enjoy something that’s just sweet and indulgent. Once you’ve had a play, come back and we’ll talk more about what it is and what Life is Strange is not.

Love is Strange was in production before Life is Strange was over, around the release of Episode 4 of 5. Love is Strange was not crafted as a response to Life is Strange’s finale, not as an output of queer rage, but is instead a work created out of love for the characters without needing to see the way the story ended. You could argue that this diminishes Love is Strange – that the work is made based on the impression of the characters, rather than a full knowledge of them from the way the story was going to end. This isn’t an idea I find personally satisfying, though, because I don’t think Dontnod had any idea either.

During the season of Life is Strange, I routinely people say they’d play the game, ignoring all the plot, if the game had Max and Chloe kiss. This was the overwhelming concern. This is a game with themes of serial killers, time travel, hate crimes, abuse, bereavement, disability and surveillance, and none of that matters to the audience I saw, the bad writing didn’t matter to them and how Warren and Nathan and Rachel Amber’s plot chunks didn’t matter because what they were there for was watching Chloe and Max kiss.

Which they do, by the way. Once.

By the time Max and Chloe kiss the game has killed Chloe at least three times.

Around the time the game asks you to kill Chloe, I drew the conclusion that this game isn’t actually about Chloe and Max kissing. This wasn’t a story about women and love, it was a story that wanted to observe women and their love, and also, strangely, wanted to kill one of them a lot.

What about time travel, though? Well, Max, in Life is Strange, has the power to reverse time and return to earlier in the narrative. This is something the story gives her, forces her – and you! – to use, then claims that she uses it too much, all starting because she saved Chloe’s life from a school shooting.

This mechanic is just using save-scumming as part of the narrative. We’ve been doing that since forever, and once upon a time, I thought it was kind of clever the way that Life is Strange let you handle this in-universe. The story of Life is Strange, though, wants to berate you for this. It wants to show you the tragedy, at the end, that’s your fault because you wanted to check both forks in a dialogue puzzle.

As a visual novel, Love is Strange is what we call a hypertextual game. It’s a game that invites you not just to play it, but to play it multiple times, and each route through the game references other routes through the game. Each route has its own charms, unique graphics, and different styles of puzzle to be solved. If you play your way through Love is Strange multiple times, you’re doing exactly what Life is Strange wants to tell you is bad, and dangerous.

In a lot of ways Love is Strange’s narrative design is the explicit inverse of Life is Strange. Where Life is Strange is expensively made and professionally published and trying to affect the style of an indie game, with its soft focus and its artful hipster soundtrack, Love is Strange is the indiest of indie projects. Life is Strange adorned itself with the air of queerness, but not too queer, and resorted to a plot that literally suggested you were better of not having tried it in the first place. Each possible plot fork in Life is Strange splits narratives that never really meaningfully change, and always wind up at the same decision, neither of which is happy.

By contrast, Love is Strange, is an indie game down to its soles. It was not made as a series of episodes, turning dials to make sure it could land the way the authors hoped the audience would respond to. It was expressing a want the authors had directly – even in the most basic ways. It does not adorn itself with licensing indie bands and Amanda Palmer, but is instead filled with the music of a creator trying to make something for this project. It is a girl-kissing, sweet-and-soft, normal-world queer-flag waving story of Portland college girls having gay adventures in Arcadia.

Love is Strange is the game you wanted.

Please, give it a shot.