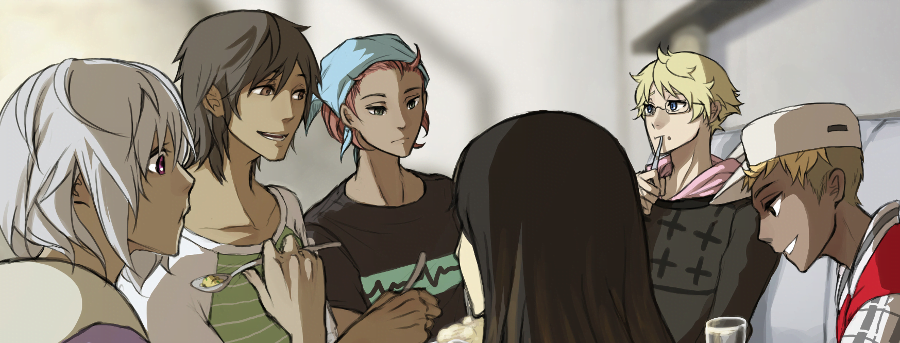

Hustle Cat is a 2016 Visual Novel by Date Nighto, which might normally get put in the ‘otome’ game category, except it’s kind of deliberately not using that particular trope set. The story follows Avery Grey, a pronouns-of-your-choice (they for this review) human form that, as seems to be a trend so far, interrupts their life of Not Doing Anything at home by getting a job at a cat cafe. This cafe is staffed entirely by painfully cute people, and you wind up smooching one of them (or dead, or worse).

Did I say dead? Don’t worry about it.

As with most games of its type, talking about plot specifics would involve digging into narrative spoilers, which I’m normally happy to do, but in the case of a Visual Novel is pretty much the content you turned up for.

You can get Hustle Cat on itch.io and Steam. It’s a more expensive title here in Australia – $30, and the US price is $20. This puts it in the higher price bracket of visual novels, comparable to a Danganronpa game, which have voice acting, animation and mini-games. Without those other ‘game’ bits to recommend them, Hustle Cat offers itself to you as a very pure experience of here are hot characters, you can smooch them.

Some folk like Visual Novels because being a fan of Visual Novels is cheap. There’s a bunch of good free ones, there’s a few that are good and cheap, and there are some – very few – that actually crest into this space. For me, the VN has always been an entity of the affordable, and that means part of me recoils at paying that much for it. What if I don’t like it? the fear creeps in the back of my mind. Visual Novels, more than other games don’t have much to engage you except characters and story, and that means that this not-small purchase has to live or die on whether or not those are good.

With that in mind, I’d like to tell you why Hustle Cat is really good.

Hustle Cat sets its tone clearly when it lets you pick your pronouns – and even tells you that you can change them any time you want. It allows for he/him, she/her, and they/them, but it also doesn’t actually attach a gender to that – characters never call you a girl, or a boy. You can be an enby who uses he/him or a girl who uses they/them. This is due to some awareness in the planning stages, and it serves the game well.

Hustle Cat’s protagonist, Avery Grey is an explicit attempts to push back against the too-generic VN Protagonist that I see mostly as a convention of Japanese porn games rather than the English Language Visual Novel scene. Avery’s a sweet character, and the world they inhabit is basically a much nicer version of the world we live in. One of my favourite details about Avery is that despite the overwhelming power over their life that the Cat Cafe seems to potentially have, there’s no official reprimand or use of that power I ever see. The problem of doing poorly at work, or the rewards for doing well are completely meaningless – Avery cares about not disappointing their coworkers.

There’s an interesting conversation to be had in this game about how you’re trying to anticipate the game’s idea of what it thinks you should be doing. I’m used to Visual Novels being pretty obtuse about finding routes, and with many of them the only real choice is to replay them and to make the opposite choice to what you did last time, pursuing something that makes the game react differently. I’m not a fan of this, but in Hustle Cat they lean into it – if your only option is to play the game six times, they’ll try to make all six character options not dreadful, unlike a lot of VNs with their obligatory One Total Asshole character count. This makes Hustle Cat a hypertextual game, where each path’s plot is informed by replaying the game, and knowledge of how other characters are living their lives gleaned from playing their route helps to inform you about what characters’ behaviour really is. Graves’ behaviour is by most standards bad, but when you see the outcomes of how it relates to the characters’ lives, you might think otherwise.

Look, there’s a lot in this game that I could unpack and talk about at length. There’s a whole bunch of fascinating stuff put into this game and while I’d love to do it, there’s only so much time. This blog isn’t the Hustle Cat Show, after all. As with other series I’ve talked about and loved, Hustle Cat is a game with a strong, consistant framework for what it considers a good relationship, the appropriate use of violence, and acceptable uses of power. It’s a Light Novel plot of a game, and it benefits from that rather than rails against it.

There’s a list of things I wanted to talk about. Like seriously, here’s the list:

- The game has a motif of being your own savior, but it also shows every character as someone rescued by someone else.

- There’s a message undercurrent in the whole story about attaining power, and the ways to do it that are both legitimate and illegitimate.

- How who you are connects to how your power expresses itself. It presents an essentialism of self, expressed through magic.

- How do spaces exist to rules of the universe? What’s the identity of a building to magic?

- The use of crossfades as sleep leading to a narrative following an extremely sleepy character.

- The literal power of trash

- The use of media as a way to communicate power – there’s an undercurrent message of the literal power of words as containers of ideas.

- The notion of the curse and what, in this game, it does or doesn’t mean.

- Acceptable violations of trust and exploitation.

See that? That’s a big list! There’s a lot to get into there! That’s a podcast series worth of topics to get into! It would be a fool’s errand to say that this game is simple.

Now, with all of that in mind, I’d like to tell you why Hustle Cat made me feel awful.

There’s some small complaints. You know, no game is beef-free. Hustle Cat does not emerge unbeefed. One of my biggest beefs is the interface – it’s hard to play quickly. You either have to rush the interface and miss bits, or you have to sit and wait for the slowly scrolling, timed text. I can understand why a director wants to control how the text is presented, but give me an option to speed it up.

And then after finishing the game and reading the wikis to see what I missed, I started to pick at the edges of my feelings. I started to wonder about it. Then I got thinking about things and examining my feelings and… and the cracks started to show.

First of all, there’s the fact (spoiler!) that you don’t get to see what kind of cat Avery becomes. I personally found this entirely acceptable – I didn’t care, because to me, the alluring (hah) thrill of ‘what if I turned into a cat’ just isn’t there. The story lacking in transformation for the player is a mark against it honestly. Transformation stories are normally a place for energetic consideration of gender themes, a thing that a lot of trans people relate to, which I know would be a selling point for my friends.

I mean, I also don’t care about coffee, something the game makes a point of showcasing, and talks about getting to like coffee as a sign of a mature palate.

And if I’m going to be totally honest, the date options really aren’t for me.

I mean…

Landry is like someone tried to make a character for me, or based on me, but grossly misinterpreted who I am, I want to kick Reese down the stairs, Graves is twice your age and as someone in his thirties I am extremely sensitive to that, Mason is hot but I feel she wants a girlfriend more than an enbyfriend or boyfriend and I don’t actually feel a need to change her to date her, Hayes just has these flashing words over his head screaming I AM WORK THAT NEEDS DOING, and the Finley ending takes a single moment to make a special point about how superhero secret identities are bad, which, I – I mean, why would you take time out of your narrative to make that point.

Why.

It’s like a personal attack.

Hell, in this game about dating someone who can turn into a cat, I didn’t actually want to date or kiss anyone in the story except Avery, which is kind of awkward, because they never do.

Ultimately, this game isn’t for me, and I didn’t feel welcomed in it, and I didn’t like the person it thought I was, but that’s fine, because this game is overwhelmingly not for me. This game is systemically decent, crafted of the highest quality, and the fact it made me feel alienated, weird, damaged and alone is not the game’s problem. It’s my problem.

I liked this game more as a performance to do – showing my friends screenshots out of context. Watching as they liked these characters, as they thrilled at them. Watching as I could show them hey, this game about dating this person exists, and you can get it, that was fun. Genuinely, genuinely fun.

Then I stopped doing that, for spoilers’ sake, and I started being in the story on my own. Alone with myself, thinking about how this game made me feel.

And I kind of felt like shit.

Strong recommendation, huh?

It’s not the game’s fault. Trust me, this game is a good game. It is really high quality. If you find yourself drawn to the visual aesthetic, you are going to find the rest of it works. You’d need the highly specific problems I do to really find the experience bad. Do not look at this game and think Talen felt bad when he played Hustle Cat, so it’s Hustle Cat’s fault.

Really, Hustle Cat is very much Queer Cutie media, and it’s that very specific kind of Queer Cuties. It’s a game that spreads its arm wide for the people like it and gives you a lot of game for your buck, and it’s full of beautiful art and lovely pictures of cute cats. Its story is all about that Queer Cutie space, and it seems that as much as it makes me feel bad, if you’re one of the people reading this, it will probably sing to your soul.

Check this game out, watch some Let’s Plays, and seriously consider buying it. This is good smooch media. You should look at it and see how you like it.