Content warning: violence, gore, demonic imagery. Basically, Is This Doom-y? Yes. It’s Doom-y.

iNTRODUCTION

Doom 2016 is, first and foremost, a pretty good videogame. I’m going to say some things about it that imply I’m unhappy with it, and that it’s not that good, but you should understand up front, it is still a pretty good shooter videogame. It’s refreshingly fast paced for a AAA videogame, the soundtrack is fantastic, and it’s got a really good sense of humour, and it includes some things I like, like pickups and secrets. The plot projects itself as being wafer thin – you wake up on Mars, and have to fight demons. Now, go fight.

While the tone of this work is going to be critical, I need to reiterate: This is probably the best, most Doom-like shooter you’ll have fun with this year or next year. It is not a bad game. It is fun. It has secrets in it if you want to look for it. You can punch enemies in the face and watch ’em go pop real good.

At the same time though, people say it’s excellent and captures the spirit of the original… I don’t think I agree. You’re cool, you do you, but no. Doom 2016 is not a game, for me, of the original game. It’s a pretty cool 2016 game that has some ideas from 1993.

It isn’t hard to get to the root of what Doom 2016 wants to be: It wants to make a game about running around and killing demons. It also wants to be fun, and fluid, and it wants to do that with an aesthetic and visual style that’s grungy and contemporary. The game isn’t trying to remake Doom even if it says it is – even if it signals it with layers and layers of constant homage to the original work.

The fundamental puzzle of every Doom level is one where the level presents you with limited resources and then presents you with ways to spend as little of them as possible. The general assertion of a Doom level is that you don’t have to take damage, though there are exceptions; some enemies do functionally unavoidable damage, and can be positioned that you have to take some damage at random spread. Yet this game isn’t actually like that:

Doom 2016 is a game full of fightboxes, full of following level markers, full of indistinct enemies against similar backgrounds, with weapons that feel soupy and unsatisfying, and an interface that feels too-stuffed with systems I don’t want to interact with. The remarkable things about Doom 2016 isn’t ‘is this system used well’ as much as, in this the years of complete removal from some of the ideas of the 90s, is ‘this system is here at all.’

iNTRICACY

Here, I want to bring up one thing I love about Doom and show how it’s not part of Doom 2016.

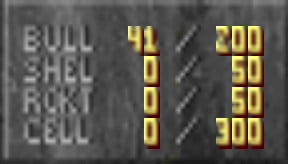

In Doom, one part of the interface was dedicated to this little box here:

This box contains trackers for the different types of ammunition your guns could use. These weapons were even divided into related types; your shells were spent by the weapons on 3, the bullets on 2 and 4, rockets at 5, and cells at 6 and 7. There were a clear number of weapons you could have, and – setting aside 2, which was kind of a desperation gun, you could view your ammunition in terms of its purpose. When you picked up ammunition, it was distinct what impact it had – you could watch this going up, and you knew what options you had available to you.

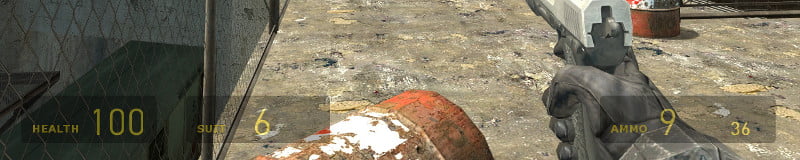

Conventionally, it’s not seen as useful to spend visual space on this kind of information. We have a certain view of how interfaces should be, now, and it looks a bit more like this:

What you show is what you care about, what you think players should care about. You can hide things to make sure players forget about them easily. The interface of Doom wanted you to think about other weapons, to think about your arsenal while Half-Life wanted you to think about the bullets in your current clip. Now, we can talk about whether or not Half-Life‘s system is good or bad (it’s neither) another time, but the important thing is, Doom was to me a game about carrying a golf bag of weapons, and knowing what circumstances made those guns better or worse.

This is a fairly fine point but it informs the weapon system. The weapon system informs the pickup system, and the visual design of the enemies. The visual design of the enemies informs the textures of the game spaces. These pieces play together, and the interface of Doom 2016 is not an interface that serves the same needs as the interface of Doom.

iDENTITY

There’s this dang tease in the early part of the game – you’re introduced to a prompt that starts to give you a backstory dump, and you respond to it by punching it, interrupting it, and moving on. I thought at that point it was a signal of the game’s decisions and pacing: Anything we tell you is going to be interrupted, so the story will be mostly made up of missing information, and instead, we can foucs on the play experience. The game wants to be fast, wants to avoid arrests in play. I was excited by this.

I’m more aware of arrests these days. One thing I really like in action games is a feeling of action. If a game lets me move and interact with my inventory, for example, or if I can idly flick weapons back and forth quickly, without it representing a major impediment to my time. Recently, Nuclear Throne was a good example of a game where the player almost never loses complete control of character for any purpose. The game then started by telling me: Arrests? Nah!

Then the rest of the game features arrest

upon arrest

upon arrest.

And that’s fine! It’s fine, sometimes you need to do something cheeky to hide the levelling. Sometimes you need to hold things up to change game flag. And there’s a sense of reality people have about how items should work, so when you get to your armour, of course the game wants to hold up and give you an animation showing you getting that item. It wouldn’t make sense any other way, right?

So the game compromises its promise. Whatever. It’s just how games are, right?

Original Doom made a lot of work out of darkness. But the darkness of Doom is cartoonish – harsh, sharp distinctions, burst into illumination with the vibrant colours of projectiles, showing you where shots came from. Spaces could be big and allow lots of dodging or tight and punish mistakes. The world was also smooth – you never had to worry about catching an odd edge or a thing Not Quite Working because of your angle of approach. Your movement was consistant and to consistant rules. You didn’t live in a world of flagged, mantelable surfaces.

That’s not the world of Doom 2016. It tries to give you a sense of the same space – action, free movement, that you’re not part of a Very Videogame Videogame, and this Videogame is Different, but it doesn’t feel different enough to me. I don’t feel like this game is okay with me missing enemies – indeed, the fightbox mechanism mean that I spend time roaming around its Big Arena areas trying to find the last thing that’s blending into its environment.

It feels like Doom sounds, not how Doom feels.

In the end, this isn’t a Doom remake. Lots of people said ‘it’s just Doom‘ and while I appreciate they want that to be true, it’s not, for me. Doom never took my camera control away from me. When Doom made me wait for things, it made me wait for movement I could see, and it rarely wanted to make me wait long. Doom‘s weapon system cared about types and matching and made me scrabble for types of ammo. Doom didn’t shy away from bright colours and clear contrast. Doom used its gloom and murk to mix up experiences. Doom didn’t promise me that we’d skip boring cutscenes, then lock me in a small room with a boring cutscene.

This isn’t a bad game.

But it’s far, far short of what I was told it was.

I doubt I’ll finish Doom 2016. It just doesn’t seem fun enough to bother.

Verdict

You can get Doom on Steam.

Verdict

Get it if:

- You want a good, modern, checkpoints-and-cutscenes AAA shooter that’s faster than the others but still plays like them

- You like Mick Gordon’s Music (which is absolutely great, buy the soundtrack)

Avoid it if:

- You notice how Doom works and love it

- You want a shooter game with minimum arrests