I picked up this game on the recommendation of my friend Caelyn, and the game’s own descriptor refers to it as an anti-adventure game. The game advertises itself with about as much story as you’re going to get: You play as the Janitor, an Alaensee girlbeast with a municipally-subsidized trash incineration job, who dreams of leaving Xabran’s Rock far behind her. In case you were wondering about whether or not she does, she does not, and the game instead focuses on the narrative of that being.

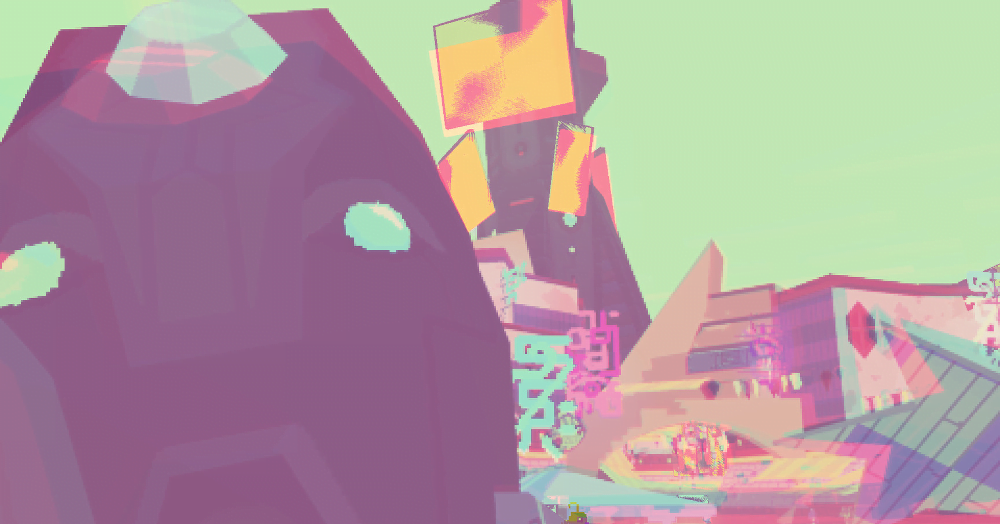

This is a beautifully stylish game. Aesthetically excellent, brightly coloured, with a wonderfully junky characterisation. What really stands out to me, what I found myself loving in this game which I otherwise didn’t love, was the music. Beautiful music, fun and funky, alien and weird, filling a space with life and vibrancy, like all these weirdo characters of all sorts of different types of people.

As a sort of supplemental piece, I’d like to suggest you go check out Chris Franklin’s video exploring this game as a game. It’s definitely a good take and if you want to look at Diary of A Spaceport Janitor as a game in the context of games, especially with Chris’ usually high-angle take. He frames his take on the game as an indie game in the same vein as Cart Life, as an anticapitalist antigame, and as an artwork with a singular message. That’s all good.

It’s also not kind of what I wanted to do here.

See, what I set out to do this month was try to play games that I can identify as queer games, games that fit a theme of ‘pride month.’ This proved harder than I expected, because the most obvious way to make a game queer is to make it about queer relationships and that almost always means Sexy Games or Dating Games, which puts us into the romantic novel space. I don’t know if anyone’s picked up on this, but I try not to talk about that stuff.

The gameplay loop is pretty simple; you wake up, you look around for things that you can turn into currency, and then you look for ways to turn them into that currency. The world you’re in is full of people doing drugs, eating bad food, selling cheap awfulness, hawking wares in a rotten way and buying garbage they don’t want. You can burn things for currency (that you get tomorrow) but you can also sell goods you find to people who buy them, but those people move around, aren’t around consistently, don’t have the same return on everything.

It’s one of your economy games, but the economy you’re dealing with is prodigiously hostile. There’s a lot of things you’d kind of assume of a game that relies on trading and scavenging like this, and every way the game can limit you, it does. Storage space is limited, you don’t get information in a clear or easily processed way, and prices aren’t even consistent. It is at its root a trading game of Dealing With Capitalism, and it makes sure that dealing is as rubbish as possible. You’re not even protected by laws – randomly, guards can just shake you down for your meager savings.

You also have just random bad luck to deal with; you can get sick, which impedes your ability to eat, and an inability to eat impedes your ability to sleep, and an inability to sleep prevents you from getting your next paycheque. As well as illness, though, you have the problem of occasionally getting Gender Dysphoria, and needing a treatment for that, which consumes nearly random cash values.

Still, it’s this economy that your main interface with the world, and it contains my favourite bit of worldbuilding in the game. See, there are people who buy dirt and containers, and people obssessing about particular magical components, but there’s also vendors who sell what you’d think of as ‘adventuring supplies’ – conventional supplies that are clearly designed for the typical adventurer. Magical guns and superior swords and spells, things whose prices are measured in thousands of times more money than you’ll ever have.

It’s a fascinating component of this game’s design; it speaks to the world as a place that you work in, but it’s not a world made for you. It’s a world made for other people; this place is colourful and bright because whoever is coming into this town on the way from point A to point B, on their quests which are clearly extremely lucrative is spending enough money to sustain an economy for just themselves and that economy has enough spillover to feed traders and hawkers and all the way down to janitors, like you.

When we talk about things in spaces, we tend to think in terms of instrumentation – in terms of the things we can interact with, and what that means for how we interact. Doom, for example, makes its instrument clear, front and centre when it starts, a big ole honking gun just sitting in the middle of the screen. Narrative Adventure games are often built around the challenge of working out what in the game is an instrument and what’s not.

Diaries of A Spaceport Janitor works from the ground up; your instrument, the things you interact with, the things that are going to drive this game for you is garbage, and the garbage of a culture of transition. Everything is something someone threw away because they were done with it. Everyone else is dealing in trash because it’s all they have.

Hell, you’re dealing with the trash other people can’t be bothered to deal with. The trash of trash, and you crave it.

I kind of resent these games, you know. The games that come at game making with a clear queer air that seem to think that because power fantasies are the things the nonmarginalised make for themselves, they should be ‘left’ to that and we should instead be making games about being miserable.

I don’t want to be seen as saying games like this shouldn’t exist. Even if there were too many games like this that existed, any single specific game shouldn’t bear the burden of the genre on its shoulder. Still, as much as we can point to a trend where women are presented in mainstream movies a particular way, we can still point to a way that queer media tends to be about spaces that other media leaves alone.

It’s a personal thing, mind you; there are a lot of people who really love games about durdling around and struggling against unfair economic systems – I mean, games like Stardew Valley and Minecraft both exist to present you with an indifferent world that you can connect to and make your own in the way you personally find the most enjoyable, and those games aren’t queer-resistant. Minecraft, the product of Hatsune Miku, even carries with it a sort of inherited queerness, and you can have queer relationships in Stardew Valley.

Yet if you delve into itch.io‘s spread of titles that become queer indie darlings, there tends to be a pretty consistent trend towards depressing and difficult. It’s just straight up hard to find games that fit the mould of ‘mainstream indie games’ that are also games about queer characters.

And so, I know I was biased against the type of game Diaries of A Spaceport Janitor chooses to be. It calls itself an anti-adventure game. The game starts with a call to adventure then punishes you for achieving it, and your optimal outcome is not to change anything, but to return to the point in the cycle you were at before you were foolish enough to try and want to change your life.

There’s an experience Chris spoke about in his playthrough which echoed in my playthrough: There can come points in this game, where between being shaken down for your money, an emergency gender dysphoria attack, and the closing of night, without even battery for my incinerator, that I staggered around the spaceport checking what was on the ground in the hopes of finding something I could eat off the ground, because if I couldn’t eat, I couldn’t sleep, and if I couldn’t sleep, I couldn’t advance to the next day, so I couldn’t get my next influx of cash. When I found some rotten food that made me ill, I was so god damned relieved because even if this was going to create a problem for tomorrow, I could get to tomorrow, and maybe deal with it then.

This is a pretty rough experience for a game to get you into, and while I’m absolutely impressed, it’s still grim as hell, pastel colours and chunky pixel art with singing aliens notwithstanding. This game gives you the experience of subsistence living, just on the far side of rough sleeping, and like, there’s no reason for me to have kept playing.

When I was starving in a raining night staggering around looking for food to, I need to repeat, eat off the ground, recovering from having been robbed and having an attack of the genders, there was literally no reason for me to keep playing this game. I did it, though, and the game had me engaged, but it wasn’t until after I hit the pillow with the mess of whatever the hell I’d chugged down rumbling in my guts to make me sick that I stopped to go: wow this is fucked up.

The next day was a festival day.

And that was nice.

I sat and I listened to the music. And I smiled. I picked up trash after the night came and the festival ended, and got back into the grind for another while.

I’ve talked in the past about an idea from Foucault, where he talked about places that exist to be passed through but never lived in; places that are inherently alienating, places that are made to be incredibly comfortable and have the conveniences of living, but not the conveniences of living long. It creates a space that is accommodating for a moment and hostile for a month.

They are decked about with signals that you don’t remain; that you need to move on; that you don’t belong; that this place is made not for you, and if you are here, you are not here to stay. These spaces are exhausting to live in, and incredibly hard to work in. Even those jobs that have the least interaction, still have the demands of the place put on them. Workers in airports aren’t supposed to hang around in the social space on their breaks; janitors need to be inconspicuous while they clean the train station. The people who work in these places aren’t meant to enjoy the benefits of this space.

They’re train stations; prisons; space ports.

These spaces Foucault dubbed as Heterotopia.

Happy Pride month!