Super Smash Bros Melee Competitive doesn’t exist.

But then again, neither does baseball.

Smash is the umbrella term used to refer to a family of videogames starting with Super Smash Bros on the Nintendo 64, released in 1999. Then in 2001, the sequel launched on the Gamecube, Super Smash Bros Melee. In 2008, then there was Super Smash Bros Brawl on the Wii, 2014 saw Super Smash Bros For The 3DS and Wii U, and most recently, Super Smash Bros Ultimate in 2018. Each of these games has a fandom scene that we’ll euphemistically call lively and a storied history that can only happen when a game is continuously pored over for actual decades.

The basic mechanisms across all five games is the same; you pilot a little character around on a stage and do thematically appropriate attacks to hurt them, which knocks them back. The more they get hurt, the more they get knocked back, so fights have a natural escalation. Rather than trying to run an opponent out of health so they collapse, fights in Smash are designed so you can fling them out of bounds on the edges of the screen, which gives everything a distinct theatricality that a lot of fighting games don’t have. It also creates a different kind of game tension as the numbers get higher; you can hypothetically survive a very long time at very high damage if you just don’t get hit.

The game is also made to be extremely high variance, with a deliberate inclusion of a lot of things made to make the game random. Powerups fall out of the sky, super powerful moves are available to some characters at literal random, and in in the later games, there’s even a game-swinging powerup that players can chase after. Stages change shape, random foes do damage, and there’s even an item that can heal the player who gets it. It’s meant to have a light, party game vibe, and powers are based on being generally equal to one another.

It’s a party fighting game for little kids.

And each of them has a competitive scene that’s playing a game that doesn’t exist.

I wanna talk about Super Smash Bros Melee Competitive, though. I wanna talk about it because it has problems that I can talk about and those problems have literally nothing at all to do with the game as if I was playing it. Not complaints, but still, criticisms I find meaningful and interesting to talk about, and which you don’t need to really understand Smash Bros as a competitive game to recognise.

I do not seek in this to try and explain to you, the actual history of Super Smash Bros Melee as a competitive game. For a start, I just don’t know that much about it directly. Certainly not in a way that makes me feel comfortable talking about it. I couldn’t do it justice. This is a game where the mechanics have been screwed in tight with layers of extra competitive rules and software redevelopment that it is now at the point where the game is being maintained to continue the existence of bugs in the math of the game in order to make sure that the game’s integrity is maintained. It’s too deep.

But also, the community of Super Smash Bros is itself the kind of thing where if I did provide a reasonably simple summary, I know there would be criticism based on what I didn’t know from a community that prides itself on a reputation of being super inclusive and approachable, as expressed by people who are entirely heavily invested in deflecting criticisms by dint of their being super inclusive and approachable. I’m not saying they’re assholes, but I am saying that everyone says their community is super welcoming and inclusive and they often aren’t the best judges of what that means.

Nonetheless, there’s a lot of content out there explaining Smash, which is something you kind of have to marinate in to learn about. If you would like to learn more about it, here are some resources I’d recommend for both learning about Super Smash Bros Melee as a tournament scene. First of all, there’s Spectator Mode, hosted by Loading Ready Run, where Certified Good Boy Adam Savidan gives a great introduction to the game and its community.

If you want to dig into the strange minutia of the game’s peculiarities, there’s the channel run by AsumSaus, which does do some very deep explanations with some really specific things. Like, it opens with a conversation about how Link has a weird extra frame of hitbox on a weird jump.

This is the kind of video that makes me convinced that I’m completely not going to play this game. It’s so fast, and the inputs are so flexible that I just feel like I’ve been handed a flute and all I can do with it is hit people. It’s full of these intricacies and that players can follow that while playing it at full speed makes me feel, very keenly, that I am in my late thirties and have never felt great about controllers.

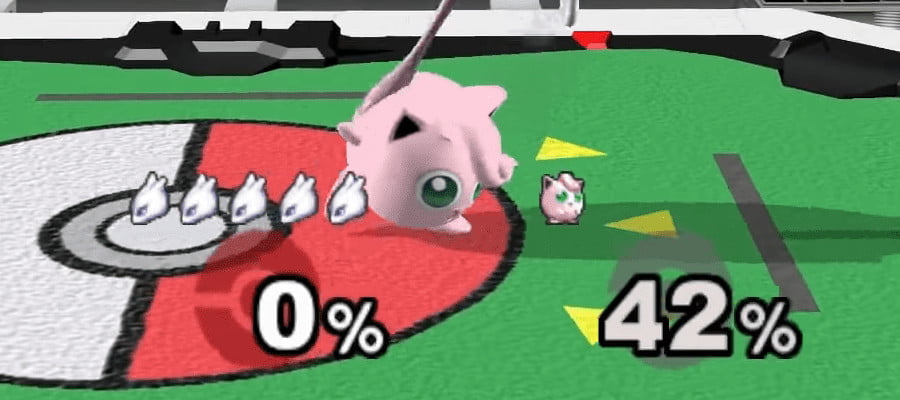

If you just want to see the kind of setting and world that Smash takes place in, in a video that shows gameplay and also kinda just goofs off with the concept space:

Not a strong academic source, but notice all these ridiculous things that can go wrong in a level?

And here’s the excellent Innuendo Studios talking about engaging with Smash as a spectator sport. I think of these three sources as a good place to go for why you talk about or know about a game you never intend to play, why you may never care to play it, and yet you can still appreciate the game as a culture.

You might notice, though, that these videos start at an hour and then it spirals out from there. The level of attention to detail in these games, and in the participatory community is pretty intense. There’s an article on this wiki that seems legit but also, I could have been elaborately trolled and how would I know?

This is a long subject, and you can get involved in it as much or as little as you want.

What you do need to know about Super Smash Bros Melee competitive for this is pretty much as follows:

- It is a game over 20 years old.

- It is a game which has had a very stable ruleset since about 2003

- It is a game whose ruleset has explicitly sought to minimise randomness in the play experience

- It is a game where a group of five players were able to dominate the game for somewhere between ten or fifteen years, depending on who you ask.

It’s very easy to think of randomness in games as being an inherent evil. The competitive scene of Melee has absolutely done what it can to address the randomness in the game, by eliminating entire mechanics and a large number of the stages. At the time of last check, at this writing, there are three stages used for competitive play, and they’re all more or less iterations on the same idea of ‘four platforms you can maneuver around.’ This randomness is meant to reduce things that players can do to make the game more about skill…

… Except for some other things that are also disallowed because they make that skill boring. Like, getting ahead on points and then stalling the game out for time is against the rules, despite that taking a different form of skill. And there are a host of other things that are disallowed but also tend to be there to respond to very specific kinds of advantages that you only can have if you’re probably pretty deep into the game as well.

Poker is often seen as a random game, but if you look at the top tables of the World Series of Poker over time, you see a lot of repeat appearances. Lots of players can get to fairly similar positions in a game that has, very pointedly, a high amount of luck involved in hand to hand. Skill in poker is often about minimising the influence of luck; there’s an entire set of skills in poker that are about avoiding what’s called a cooler – a game state where it’s very reasonable to be aggressive, but which where you have almost no chance of winning. Sure, there are games determined by flipping single cards, but most players when they are playing well are letting rounds be determined by those flips, and very rarely letting whole tournaments be determined that way.

Typically, if you see the same names or the same strategies at the top of lots of tournaments, though, that means there’s probably a problem…

… and Smash had a period where there were five people whose presence was so dominating, sources claim that they would coordinate to avoid going to the same tournaments so as to not ruin the experience for everyone. I can’t verify that one at this point, but it sounds feasible to me based on all the other stuff I’ve heard about how overwhelming these five players were. And this is a period where the game, without major updates to the rules, persisted in that state for somewhere in the realm of a decade.

Typically speaking if a game that has high amounts of variance has been tuned to the point of removing that much variance, I would assume the solution would be to then to reintroduce some variance; to make it so that there were ways that someone could draw the nuts against one of the Five Gods, to just at least make those encounters potentially different to what you expect. It’s what I’d normally call ‘overtuned.’ Whatever can make the game uncertain is not making the most important games uncertain, and so…

The era of the five gods.

But the other thing about that era, that decade is that it was a decade. A decade in most sports is a time when you can’t have the same five top players because some of them are going to age out of it. What was a concern for a time in Melee competitive, though, was the hardware aging out of it. Long-term protracted play of the plastic hardware that was designed to be toys for children and could already have modestly unpredictable effects took a physical toll on twenty-year old devices, and that created a demand for ‘good’ controllers of the type and generation. Not ‘this controller is broken now because of its age’ but rather ‘this controller isn’t quite being snappy enough and it’s causing me a mechanical disadvantage in a tournament.’

These are not concerns for most games. Baseball does not have to worry about there being a limited supply of baseballs. And yes, specialised services are coming up to meet the demand for the competitive Smash community, with modders and repairers making sure that a limited supply of hardware is made to last, and new replacements filter in, but that’s a shift in a cultural space, and in cultural presence. Once, Gamecube controllers were a standard, $50 kind of purchase in stores; now, getting one that’s game-ready for the competitive scene can run $400.

Okay, so what, right? This game has smoothed off all the fun randomness so now it’s a boiled egg of a competitive scene and it’s now only playable by people who can sink a lot of time into it buying controllers that are worth more than the entire console was new. Clearly, then, this is a Bad Game and I am here to poke fun at it.

But I’m not.

I’m really, really not.

These are things I find interesting. It’s okay to have a game so smooth and frictionless that the entire rules set can be mapped out ahead of time such that single individuals can go on years-long winning streaks. Hell, that’s how chess works, and that’s a game with a lot more competitors (sorry) and a lot more history. It’s okay for a game to be hard to play because of hardware constraints – and my thinking there is then it would be good to do what we can to get rid of those constraints.

What I find most interesting though, is that Super Smash Bros Melee competitive is a game made within a game. It is a game you need Super Smash Bros Melee to play, with all the limitations and boundaries that implies, but, which these people have made, and do play, and do love. It is less of a game imposed and more a game grown; a folk game of two parents, with rules from one parent and rules from another; but the rules of one cannot displace the rules of the other.

It cannot mean anything except what the players choose for it to mean.

As Jesper Juul forwarded: All games are half-real, a mingling of real rules and fictional worlds. Super Smash Bros Melee competitive is a game that doesn’t exist; you can’t get it off a shelf and you can’t make it in your home. But you can play it, any time you find someone you want to play it with, and your reason for doing so may have nothing to do with such meaningless things as there were five people who were really good at it for a decade.

“Well, yes, but it’s not about the football.”

― Terry Pratchett, Unseen Academicals

“You’re saying that football is not about football?”

“It’s the sharing,” she said. “It’s being part of the crowd. It’s chanting together. It’s all of it. the whole thing.”